In our first podcast interview, California Assemblymember Phil Ting, D-19th District, talked with us about anti-Asian sentiment because of this pandemic.

Welcome to Race and Coronavirus

We are reporters and editors with decades of journalism experience between us. Levi, pictured on the left, spent most of her career at the San Jose Mercury News and has specialized in technology and business news. Pati, at right, is editor in chief at San Francisco magazine and has been a demographics editor at the San Francisco Chronicle, among other places.

As longtime storytellers, we know we are in the middle of one of the biggest stories of our lives. Race and Coronavirus is going to address something close to our hearts: tracking the effects of this pandemic on minorities and immigrants. Because even though we keep hearing that COVID-19 doesn’t discriminate, we also know that in the United States, black and brown people are being disproportionately affected on many different levels.

We’re talking with those who are being impacted, plus the people who are trying to help them. We’re having conversations with experts, advocacy groups, newsmakers and news gatherers. Each week, we will bring those conversations to you along with related stories that delve deeper into the issues we discussed.

Here’s a link to our first post and podcast, where we talk more about why we started Race and Coronavirus. (And our newsletter won’t always be this long. We just wanted to introduce ourselves!)

Asians bear brunt of COVID-19 blame

By Levi Sumagaysay

Lifelong San Francisco resident Sandy Fong-Navalta was on Muni recently, heading home from work when she witnessed a white male yell at an elderly Asian man for being a "rude, f---ing ignorant Chinaman." The Asian man had put his hand up when someone got too close to him on the bus. “You’re the reason coronavirus came to America!” the white male continued in response to the elderly man’s gesture.

Fong-Navalta, whose sister-in-law is Race and Coronavirus co-founder Pati Navalta, said she has witnessed or felt tension in San Francisco quite a bit since the first reports of coronavirus -- a homeless man recently told her she was “spreading the corona” -- and that it has come “to the point where I’m almost desensitized to it.”

As some people blame the rise of coronavirus on China, where it originated, the FBI has warned about a possible rise in hate crimes against Asians in the United States. Businesses owned by Asian Americans are being vandalized. Some Asian Americans are literally arming themselves in case they are physically assaulted, like an Asian family that was stabbed at a Sam’s Club in Texas in March, reportedly because of coronavirus. And advocacy groups, policymakers and others are having to dole out advice on how to deal with it all.

Also in San Francisco in early March, Yuanyuan Zhu was on her way to the gym when a white male in his 40s who “looked like a regular person” spat on her after he shouted “F--- China.” He also yelled at a passing bus to “run ‘them’ over.”

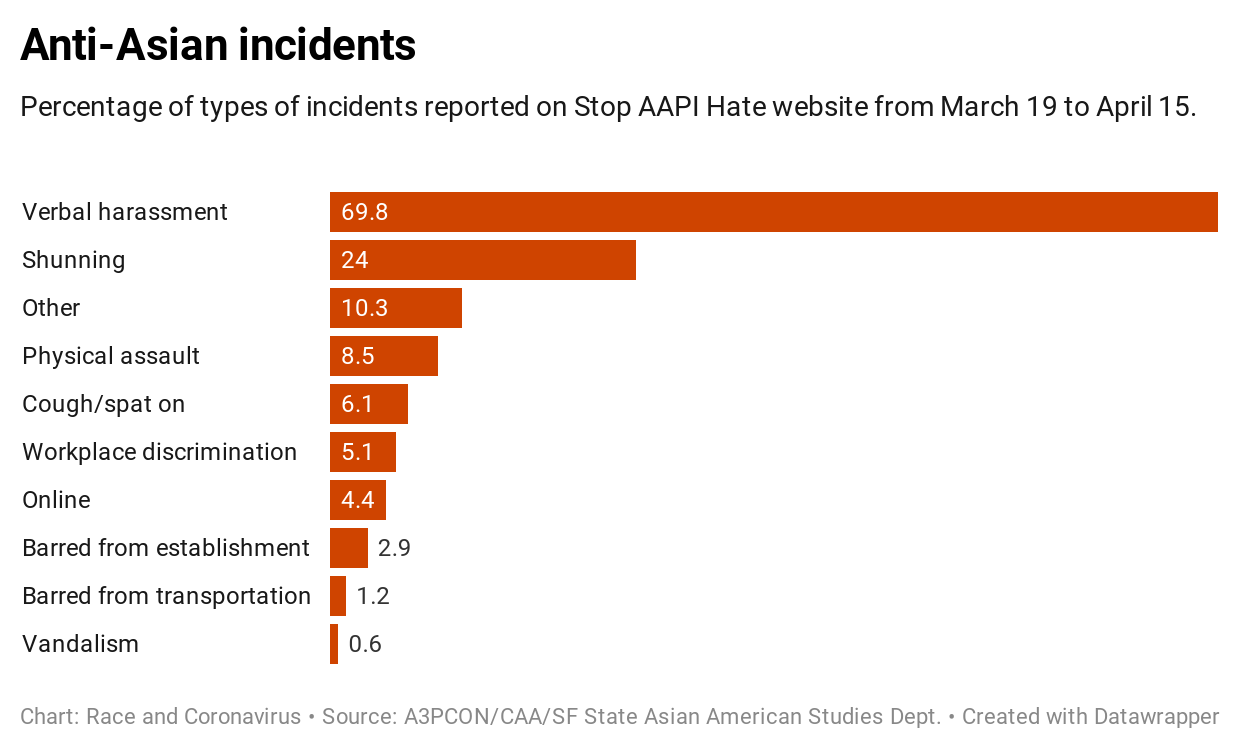

She told her story on social media and to the New York Times, but she recently told it again to journalists who tuned in for a recent online press conference held by Chinese for Affirmative Action, Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council and San Francisco State University’s Asian American Studies Department, which have teamed up on Stop AAPI Hate, a website where people can submit anti-Asian incidents. In the four weeks since the site was created, it had collected nearly 1,500 reports — and by Tuesday, that number was up to 1,716, according to Chinese for Affirmative Action SF spokesman Eugene Lau.

“I was panicked,” Zhu said. “I just walked faster and into my gym.” She said it was “hard to imagine that this would happen in the Bay Area,” which is known for its diversity, and that it’s important to speak up and collect data about what’s happening.

Russell Jeung, head of Asian American Studies at San Francisco State, said the density of San Francisco, its residents’ reliance on public transit, and large Asian population are probably why 41.8% of the reported incidents happened in the city. New York City was second, with 16.7% of the reported incidents.

“When coronavirus hit, I knew Asians would be targeted,” Jeung told Race and Coronavirus. The incident reports are coming from different ethnic groups because many Asians are mistaken for Chinese.

The professor blamed politicians for “riling up their base” and trying to avoid responsibility for “not doing enough” in response to the novel coronavirus. “Their political rhetoric opens up hate.”

He also pointed to the long history of anti-Asian racism in this country. Chinese miners were driven from their homes and even killed during the 1880s. Jeung said the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned Chinese laborers from entering the United States, has “eerie parallels” to U.S. sentiment today.

“Back then there was a recession and whites were losing their jobs,” he said. “Now we’re (headed toward) a depression and whites are losing their jobs.”

A fairly recent parallel is the backlash against Muslims after the September 2011 terrorist attacks, Jeung said, adding that then and now, America was and is said to be at war.

“The difference is President (George W.) Bush said we shouldn’t tolerate racism against Muslims,” he said. “President (Donald) Trump insists on calling it the Chinese virus… with social media and memes, it really shapes people’s subconscious.”

In a podcast interview with Race and Coronavirus, California Assemblymember Phil Ting responded to whether he had been personally affected by anti-Asian backlash since the beginning of this crisis. He said that he had, but could not go into detail.

"This virus has really given people a license to hate," he said. Ting represents the 19th district, which includes parts of San Francisco and San Mateo counties. Ting applauded the creation of the Stop AAPI Hate website, citing the importance of collecting data for policymaking. However, he cautioned that reported numbers may not reflect the true number of incidents. “There are probably... more people who decided not to step forward or haven't even heard about this website.”

Cynthia Choi, co-director of Chinese for Affirmative Action, said as much during the press conference: “Consider this an undercount. Lots of incidents are unreported.”

How can Asian Americans deal with the verbal harassment, shunning, being discriminated against at their workplaces and in other businesses, and even physical assaults?

The groups that held the press conference underscored the importance of reporting and tracking the incidents as a way to inform authorities and officials who can enact policies and enforcement to combat the hate.

“Racism can be traumatic,” said Alicia del Prado, a psychologist from Danville who said she has seen patients who have been affected by anti-Asian sentiment.

She said she tries to help her clients “feel supported and understood so they do not internalize the negative messages and do not go to self-blame, self-hatred, paralyzing fear, or other negative outcomes.”

Jeung takes some comfort in history: “Asian Americans have always resisted, so that gives me strength. The Japanese won redress and reparations (for their internment during World War II). America can apologize for its actions.” He hopes that people use lessons from the past to politically mobilize, and is encouraged by the fact that there are more Asian American leaders in power these days.

Ting mentioned that “we have the largest Asian American caucus in California state history.” He said the Asian American caucus has stood against hatred in all forms and have the support of other caucuses on this issue. “If you ever think that representation doesn't matter, it absolutely does matter.”

News roundup

Coronavirus numbers don’t add up – for some

By Pati Navalta

(Unsplash)

The numbers are incomplete.

These simple four words can be found on the website of We Must Count, a coalition of health and racial equity and civil rights organizations calling for the federal government to provide more funding for consistent, comprehensive data. As more headlines emerge of the pandemic impacting a disproportionate number of people of color, the question begs to be asked: Just how bad is it?

Even with incomplete data, the numbers paint a bleak picture.

According to a recent report by APM Research Labs, the latest available COVID-19 mortality rate for black Americans is 2.3 times higher than the rate for Asians and Latinos, and 2.6 times higher than the rate for whites. “For each 100,000 Americans (of their respective groups), 40.9 Blacks have died,” the report states, “along with about 17.9 Asians, 17.9 Latinos and 15.8 Whites. These rates are so disparate it can be hard to appreciate what this means.” The report concludes that if black Americans had died of COVID-19 at the same rate as white Americans, at least 10,000 more black Americans would still be alive.

"When white America catches a cold, black America catches pneumonia," Steven Brown, a research associate at the Urban Institute, a Washington-based think tank, told CNN Business.

While people of color are not more susceptible to the pandemic, years of racial disparities have put them at greater risk. Environmental injustices, unequal access to health care, and food insecurity, for example, have long been symptoms of deep, systemic inequities in the United States. COVID-19, what New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo once described as a “great equalizer,” is in fact a great magnifier of how unequal we really are.

BBC reports that disproportionately high numbers of ethnic-minority households in North America and Europe live near incinerators and landfills, and schools with high proportions of minority students are located near highways and industrial sites. “Air quality, which early data is highlighting to be a potential risk factor for Covid-19, is also a risk factor for respiratory health,” Grania Brigden, who leads the tuberculosis department at the lung health organization The Union, told BBC.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, black households were twice as likely to face food insecurity as the national average, with one in five families lacking regular access to healthy food. As the BBC report points out, this was before the pandemic forced layoffs and dwindled resources at food banks. This lack of consistent nutrition has resulted in years of underlying health conditions in the African American community, namely diabetes, heart disease and hypertension—all of which puts COVID-19 patients more at risk.

In the Golden State, the California Department of Public Health reports that Latinos have the highest rate of positive coronavirus cases at 38.9%. This trend is consistent in San Francisco, where Latinos account for 25% of COVID-19 cases but make up only 15% of the San Francisco population, as reported in the Los Angeles Times. During a recent press conference with Mayor London Breed, city officials cited possible reasons for the high numbers in the Mission District, including multi-family or multi-generational households, or Latinos holding jobs such as home-care aides that require them to go to work.

What poses the most danger, however, is the unknown.

Dr. Grant Colfax, San Francisco’s health director, told the LA Times that some Latinos are declining to participate in city programs that trace an infected person’s contacts to prevent the spread of the virus. In a pandemic during which the country’s president has tightened immigration policies and doubled down on calls for building a wall along the Mexican border, they simply don’t trust that participating in a government-led program won’t lead to deportation.

Native Americans, on the other hand, don’t have a choice. A recent analysis by The Guardian revealed that 80% of state health departments have released some racial demographic data, which has already revealed stark disparities in the impact of Covid-19 on blacks and Latinos. “But of those states,” it concludes, “almost half did not explicitly include Native Americans in their breakdowns and instead categorized them under the label ‘other’.”

“By including us in the other category it effectively eliminates us in the data,” Abigail Echo-Hawk (Pawnee), director, urban Indian health board and chief research officer, Seattle Indian Health Board, told The Guardian.

The lack of consistent data across states is not only egregious, it’s a matter of life and death. Data is what often determines the distribution of funds and crucial resources, and without it, some of the most vulnerable populations are left unaccounted and uncared for.

What we know is already bad. What we don’t know is most certainly far worse.

The bright side

Asian Americans are doing what they can to push back against the hate.

Gold Rush, a business accelerator, partnered last month with delivery provider Postmates to feature Asian restaurants for a week and a half. The promotion, part of Postmates’ “order local” campaign, highlighted Asian restaurants in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles via a special carousel that popped up when people called up Postmates on mobile or web.

Megan Ruan, Gold Rush’s venture director, said Asian influencers and celebrities including director Alan Yang, the Shibutani siblings, presidential candidate Andrew Yang, and designers Prabal Gurung and Laura Kim helped promote the campaign on social media. Some of them raffled off Postmates credits to their followers.

Gold Rush is now in talks with DoorDash for a possible similar campaign, Ruan said.

Coming up

We explore this pandemic’s effect on essential workers and interview U.S. Rep. Ro Khanna, D-17th District, and gig workers Vanessa Bain and Jon Wong, on our next podcast.

Let us know what you think: editors@raceandcoronavirus.com.

For business and media inquiries, email info@raceandcoronavirus.com.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram or LinkedIn.

Partner of Bay City News Foundation, which publishes free local news at LocalNewsMatters.org.