While the announcement that nobody in managed isolation will be allowed out early on compassionate grounds might sound reassuring, its legal basis appears extremely shaky, writes law professor Andrew Geddis.

As recounted by The Spinoff’s own Justin Giovannetti, there’s no doubt that last week’s Covid-19 traipsing travellers omnishambles caught the government unawares. Indeed, I think it revealed a perhaps unconscious complacency, one shared by the general public, that we’d basically got the virus well and truly licked.

Sure, overseas holidays remain off the cards for the foreseeable. And some sectors of our economy are going to be completely ravaged. However, safe behind our oceanic moat, we can pretty much get back to living like we are used to. Rugby games. Social brunches. Tinder hookups. Team five million, for the win!

Which is why the realisation that a return of Covid-19 – and its associated level three or four lockdown rules – is but a wrongly released coughing traveller away came as such a brutal shock. And the revelation that even St Ashley Bloomfield is a man capable of error, presiding as he does over processes that are prone to failure, reminded us of how tenuous our current situation still is. We’d put it out of our minds that, to steal a phrase from the IRA, the virus only has to be lucky once while we have to be lucky always.

That shock generated an immediate response. In came a new minister, Megan Woods, along with the army to oversee the isolation procedures. No-one will now be released after 14 days of isolation without a negative Covid-19 test. And all applications for early compassionate release from managed isolation will be refused, at least until the system can be rebooted to allow for it.

All of which makes sense from a political optics and general policy standpoint. The government’s hard-won electoral credit for competent management is on the line here. And while robust border isolation measures can never be enough – remember, the virus only has to get lucky once – they are a critical element of our ongoing Covid-19 response.

But, you just knew there’d be a but. From a legal standpoint, the halt to all compassionate exemptions from managed isolation looks decidedly dodgy to me. Here’s why.

The controls on those entering New Zealand from overseas are contained in a Health Act notice promulgated by Bloomfield on April 9. To simplify, it says that everyone (apart from air crew) coming into the country must be isolated for at least 14 days – and up to 28 days if the director general is not satisfied that they meet “low risk indicators”. This last requirement, as I explained to RNZ, empowers Bloomfield to demand that people take Covid-19 tests; unless you pass them, he can make you stay in isolation for another fortnight.

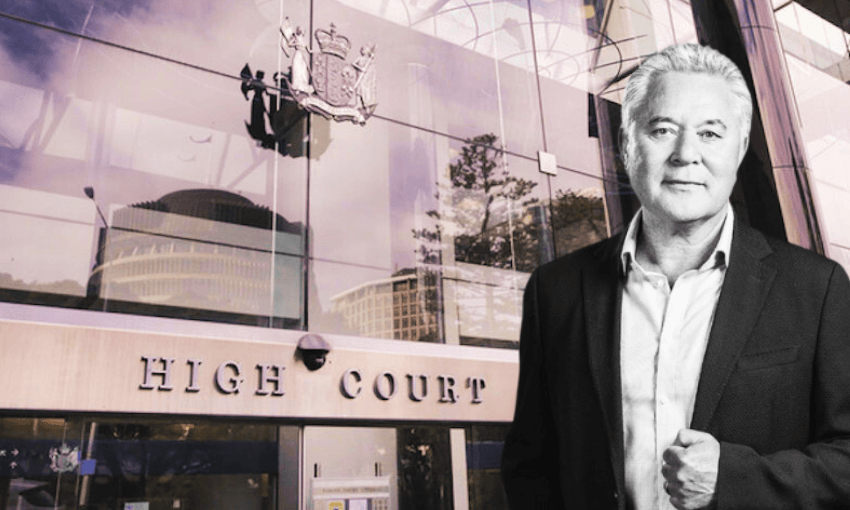

However, the Health Act notice also allowed for some exemptions from this 14 day isolation requirement. In particular, the notice allowed for it to be set aside on “compassionate grounds”, or in “exceptional circumstances”. And as the High Court made clear in a case called Christiansen v Director General of Health, those exemptions had to be properly applied by the director general.

Now, there’s been some misunderstanding (perhaps deliberate) as to what the High Court decided in this Christiansen case. My Otago colleague, Simon Connell, has a good explanation of what it was (and was not) all about:

… the government made some rules about self-isolation that allowed for exemptions on compassionate grounds, but applied them in a way that did not allow for exemptions on compassionate grounds. Rather than give the government another go at following their own rules, the court made the decision for them because they were running out of time. What the government did after that is on them.

But following the early release of the traipsing travellers to attend their mum’s funeral, the government now says that these exemptions will no longer apply and that everyone is going to have to do their 14 day isolation stints.

At one level, this then becomes something of a fait accompli. If the government says you have to stay in isolation for 14 days, and won’t let you out until that time is up, then that’s what is going to happen to you. What, though, if there is another Mr Christiansen out there who refuses to accept that he (or she) must miss the last few hours with their dying parent, or the funeral of some loved one? I think there’s a couple of pretty good grounds for arguing that they shouldn’t have to do so.

First of all, here’s how the decision to cancel compassionate exemptions was publicly announced:

Health minister Dr David Clark says he has required the director general of health to suspend compassionate exemptions from managed isolation, in order to ensure the system is working as intended.

It will only be reinstated once the government has confidence in the system

However, the power to grant/refuse compassionate exemptions (or even allow for such exemptions at all) doesn’t lie with the minister. Under the Health Act notice, it lies with Bloomfield. And the provision of the Health Act permitting the notice to be issued makes it clear that such powers can only be exercised by Bloomfield (or another medical officer of health).

Because, it is important to note that when it comes to the Health Act and the various powers it confers in an epidemic situation, Bloomfield is not acting as the director general of health. He’s acting as a medical officer of health. As such, it’s strongly arguable that the normal state sector rules of accountability/ministerial direction don’t apply to his functions in this regard. Indeed, this is a point that Bloomfield himself has been at pains to make clear in the past when stressing that his decisions to issue and revoke Health Act notices have been taken independently.

And as such, if Bloomfield (as a medical officer of health) has stopped applying the compassionate exemptions provisions of the Health Act notice because minister Clark “required” him to, then he is acting under dictation rather than exercising his statutory functions. And if Bloomfield hasn’t properly exercised his statutory functions, then the decision to suspend compassionate exemptions is unlawful.

So, were this decision to get challenged in a court, the government would likely have to claim that it was Bloomfield that actually made the call to end compassionate exemptions independently, and that Clark was just big noting when he said he did so. Much like Mayor Goff did in regards the decision to stop Lauren Southern and Stefan Molyneux from speaking at Auckland Council owned venues.

Which then brings us to the second, and possibly more important, potential problem for the government. You see, the power to grant compassionate exemptions has not been rescinded or removed. It’s still in the relevant Health Act order (again, see here at paras 5(g) & 5(i)).

What instead appears to have been decided is that there will be no circumstances at all in which the director general can be sure that an individual represents a relatively low risk of transmission of Covid-19, so no-one can meet the relevant criteria for compassionate release. But that decision then appears to remove a possible outcome without even considering the individual facts of each application – which is precisely what the High Court pinged the officials for in the Christiansen case.

In response, the government effectively would have to argue that the current system of permitting some compassionate releases is so unreliable that it cannot be trusted, no matter how well founded the case for its use may be. Which is not only a potentially embarrassing argument for it to have to run, but also seems overly strict in application.

After all, compare two individuals. One has come back to New Zealand from the Cook Islands (which has been declared Covid-19 free since April) to visit a dying relative and repeatedly tests negative for the virus. The other comes to New Zealand from the USA and also tests negative for the virus. Why is the first person deemed too risky to release from isolation on compassionate grounds after (say) 10 days, whereas the second automatically will meet the “low risk indicators” necessary for release after 14 days?

As such, I suspect that the government might struggle in court should another Mr Christiansen seek to challenge the decision to suspend all compassionate exemptions. Meaning that I’d expect it to move reasonably quickly to give this matter a somewhat more stable legal basis. Added to which, the Health Act notice governing those arriving into New Zealand expires at midnight on Monday, 22 June. So something will have to be done to extend it, with or without changes in place.

What that “something” then might look like, I guess we shall see this week.