As the forum on ‘reconnecting’ gets under way, Siouxsie Wiles explores the critical factors we need to consider.

Spinoff coverage of the Covid-19 response is made possible thanks to support from members. Click here to learn more.

One of the big questions I’ve been asked a lot over the last few months is this: What does the future look like for Aotearoa New Zealand if Covid-19 continues to rage overseas? It’s a question tackled in a report released yesterday by the expert advice group chaired by Sir David Skegg, which will be the centre of discussion at today’s Reconnecting New Zealanders to the World Forum.

I think we can all agree that different people will have different ideas about when and how we should be opening up to the rest of the world. And those ideas will depend on many things, including their beliefs and understanding about the seriousness of Covid-19 and the level of risk they are willing to accept.

To my mind, there are two main issues at stake. The first is at what stage can we safely abandon our elimination strategy and how does the vaccine rollout figure in all that? The second is, if we can’t safely abandon our elimination strategy just yet, how can we safely begin to open up our borders?

Does the vaccine rollout mean New Zealand can soon abandon the elimination strategy?

If there was one silver lining from the pandemic, it would have to be the development of safe and effective vaccines to protect people from Covid-19. It has been incredible to see just what can be achieved, and how quickly, when money is no object and the world’s research community race to jump on board. And while the vaccines really are remarkably safe and remarkably effective, none of them is 100% effective. We also know, both from the clinical trials and the real-world deployment, that the different vaccines offer varying levels of protection. So, while any vaccine is better than no vaccine, some offer better protection than others. Of course, we also still don’t know how long the vaccines protect us for either and whether this will be impacted by new variants of the virus evolving.

But putting those uncertainties aside, and focusing on the fact that no vaccine is 100% protective, what do vaccines mean for us abandoning our elimination strategy anytime soon? Before I tell you what I think, it’s important to recognise that most countries rolling out vaccines are doing so against a backdrop of widespread community transmission. That means every person vaccinated is a potential life saved and a move towards hopefully less community transmission. New Zealand is not in the same position. Because we currently don’t have community transmission (fingers crossed for Tauranga …), the issue for us is more around how many people need to be vaccinated to limit community transmission. I firmly believe we should be thinking about our responsibility to protect those in our community who can’t be vaccinated or who might have been vaccinated but haven’t mounted a protective immune response. This is what some people call “herd immunity”, though I prefer to call it “community immunity”.

We can get some idea of the coverage we need for community immunity from modelling, but we can also watch what is happening with cases, hospitalisations, and deaths in countries that are rolling out the vaccines. Of relevance to us is Israel, because it is also using the Pfizer BioNTech vaccine. It also can’t vaccinate everyone because the Pfizer vaccine has only just been approved for people over 12 and the trials on younger children haven’t finished yet. It’s looking like we’ll have data on the safety and efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine in 5- to 11-year-olds by September, but probably not until November for younger children.

To date, Israel has recorded over 905,000 confirmed cases of Covid-19 and more than 6,500 deaths. To put this in perspective, Israel’s population is almost nine million people compared to around five million in New Zealand. The Middle Eastern country has experienced two major waves of Covid-19. The first peaked in mid-October 2020 with an average of about 6,200 cases per day and 38 deaths per day. The second wave peaked in late January 2021 with an average of 8,600 cases per day and 64 deaths per day.

As well as using restrictions to bring the second wave under control, in December 2020 Israel also began rolling out the Pfizer vaccine to people over 16. As of Monday, 62.4% of the country’s population are fully vaccinated. Daily confirmed cases came down to a low of around 10 and daily deaths to between one and three. But after restrictions where loosened the seven-day rolling average for confirmed cases has started shooting up. They’re now back to almost 4,000 cases a day. Deaths have also started to increase, up to a seven-day rolling average of 10 a day.

While many children appear to be less at risk of having a serious Covid-19 infection, the risk isn’t zero and we’re starting to see reports of more and more children being hospitalised, especially in the US. According to official figures, the hospitalisation rate for under 17s among Americans is rising exponentially and is the highest it has been during the pandemic.

I think it is safe to say that abandoning our elimination strategy before our children are able to be vaccinated means accepting that many of our children will get sick and some will die. And its highly likely that burden will fall disproportionately on Māori and Pasifika families. I think it would be abhorrent to allow that to happen. And if you think we can accept a small number of kids needing to be hospitalised, it might help to know that Starship’s Intensive Care Unit is the only dedicated children’s intensive care in New Zealand. It’s at critical capacity every 48 hours. And that’s without Covid-19 in our community. Right now they are fundraising so they can create space for 10 more beds.

Can we maintain elimination but still open up?

Sticking to our elimination strategy for now means two things: limiting introductions of the virus into the country and stamping out community transmission if it happens. I think what’s happening in New South Wales shows that if we do get community transmission with the delta variant we really can’t mess around. I was relieved to hear the Covid response minister Chris Hipkins say the government’s response to finding delta in the community here was likely to be “swift and severe”. While we’ve managed for a year to stop Covid-19 using alert level three restrictions, given how much more infectious the delta variant is, we should definitely prepare ourselves for the fact it’s likely to take alert level four restrictions to bring a delta outbreak under control.

Of course, that will depend on the size of the outbreak. But the less often people use the Covid Tracer App, wear masks, and get tested if they have symptoms that could be Covid-19, the longer it may take to identify a community case – and so the bigger an outbreak is likely to be before we realise it’s happening. That means its on all of us to do our bit.

So what about limiting introductions of the virus into the country? Obviously, the big bottleneck for us is the capacity within our managed isolation and quarantine system. The great hope was that vaccines would protect against people getting infected and being able to spread the virus, and that would mean that vaccinated people could have skipped MIQ. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like the vaccines work like that. Or at least not 100% of the time. In which case it would be extremely risky to allow vaccinated people to skip MIQ, or even have a shorter MIQ. Other countries are trying this out, so I guess we’ll soon see how successful a strategy it is.

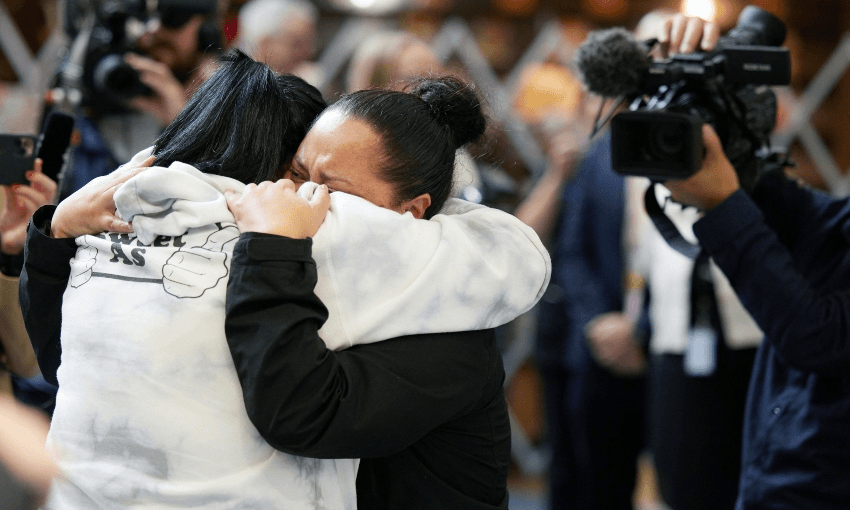

For now, though, I think we need to be patient a little longer. I would desperately love to see my family overseas or to have them be able to come to New Zealand. But our priority should be to keep Covid-19 out until our children can be vaccinated. And we’ve all embraced the regular wearing of face masks.

Until then, we need to remember that we are privileged to be living without community transmission of Covid-19 and with a safe and effective vaccine being made available to us all over the next few months. Most of the rest of the world doesn’t even have one of those things.