A long edition for your leisurely Sunday. Thanks for your patience

India Policy Watch #1: Call Of Duty

Insights on burning policy issues in India

- RSJ

Many among you of a particular age might remember a familiar trope from old Hindi films. A key protagonist, grievously injured or sick, is wheeled into the operation theatre. There’s a small red bulb on top of the door that turns on. Grim music plays in the background. After a while, the surgeon steps out, take off his gloves and looks at the assorted mix of anxious relatives with resignation. Then he says, “ab inhe dawa ki nahin dua ki zaroorat hai” (he needs prayers now; not umm… paracetamol).

That’s how I feel when I hear public discourse in any democracy get tangled up between rights and duties. Not a lot of good has come out of exhorting people to do their duty in the history of this world. So pardon my anxiety when I find constitutional functionaries conflate rights and duties, or worse, seem to privilege duties over rights. But that’s exactly what I have been coming across in the past two months. Two examples will suffice. Last week the PM made these remarks in an event organised by Brahma Kumaris Sanstha:

At the same time, we also have to admit that in the 75 years after Independence, a malaise has afflicted our society, our nation and all of us. It is that we turned away from our duties and did not give them primacy. In the last 75 years, we only kept talking about rights, fighting for rights and wasting our time. The issue of rights may be right to some extent in certain circumstances, but neglecting one's duties completely has played a huge role in keeping India vulnerable.

India lost considerable time because duties were not accorded priority. We can make up for the gap which has been created due to primacy about rights while keeping duties at bay in these 75 years by discharging duties in the next 25 years.

A few days later, the President had this to say in his address to the nation on the eve of the Republic Day:

Rights and duties are two sides of the same coin. The observance of the Fundamental Duties mentioned in the Constitution by the citizens creates the proper environment for enjoyment of Fundamental Rights.

….Patriotism strengthens the sense of duty among citizens. Whether you are a doctor or a lawyer, a shopkeeper or office-worker, a sanitation employee or a labourer, doing one’s duty well and efficiently is the first and foremost contribution you make to the nation.

There are many, and their numbers are probably rising in India, who might wonder what’s remotely problematic with this kind of framing of rights and duties? Isn’t it true that we, Indians, don’t do enough for our country? Or, is this not what JFK meant when uttered those famous lines - “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” Isn’t a call for public service and invoking a spirit of self-sacrifice for nation-building important? This is what leaders are supposed to do, they might say.

I won’t disagree so long as there’s clarity on the nature of rights and duties and where they are placed in relation to one another. This is often misunderstood in India where duty or its nearest equivalent Sanskrit term, dharma, has great civilisational and cultural significance. Rights are often seen as some kind of a western enlightenment imposition on our society which otherwise knew its dharma and its karma. Unfortunately, this as we will see, reflects both a shallow understanding of rights and of dharma.

Rights Aren’t Earned

The first notion to appreciate is that regardless of social, ethnic or temporal differences, an individual is born with certain rights. You could call them fundamental or inalienable. That she is endowed with these rights is prior to any other knowledge about her. This privilege of rights is what creates a corresponding set of duties among others. For instance, the right to life places the onus on others to not kill her. This can be of a legal nature which is enforceable by laws of the society. Or, in case of other rights, the onus on others could be a moral one which is then protected by a code of living together that’s understood by all. This onus then is the duty that an individual has towards rest of the community. It stems from accepting that others have rights. In other words, rights are ontologically prior to duties. This is the basis for the creation of any community. You respect individual rights, you create codes to protect them and living by that code becomes the duty of the members of the community. This is how societies are built.

Ronald Dworkin, the American philosopher, in his book Taking Rights Seriously, calls rights as ‘trumps’ that can be used to overturn any justification of collective imposition on an individual:

“Individual rights are political trumps held by individuals. Individuals have rights when, for some reason, a collective goal is not a sufficient justification for denying them what they wish, as individuals, to have or to do, or not a sufficient justification for imposing some loss or injury upon them.

We may therefore say that justice as fairness rests on the assumption of a natural right of all men and women to equality of concern and respect, a right they possess not by virtue of birth or characteristic or merit or excellence but simply as human beings with the capacity to make plans and give justice.”

Between Rights And Duties

But is being a rights absolutist enough to have a functioning and effective society? What’s the kind of interplay between rights and duties? Are there any grounds to limit the definition of a right to serve a larger public benefit? This is particularly tricky territory. A useful framework to think about this is to use what’s called “the Hohfeldian incidents” in jurisprudence. Named after the American legal theorist, Wesley Hohfeld, it explains the internal structure of any right to have four components or ‘elements’, namely, privilege, claim, power and immunity. Understanding this ‘molecular structure’ of a right is key to understanding its interplay with duty.

Privilege: You have the right to sleep on a weekend afternoon. This right is a privilege. You have no duty not to do it. No one can say it is your duty not to sleep on a weekend afternoon.

Claim: You have an employment contract with your employer and this gives you the right to be paid your salary. This right is a claim. That is you have a claim on your employer to pay you a salary. And your employer has the duty to pay you the wages. So, a claim-right always comes with a duty for someone who is the bearer of that duty (in this case the employer). The direction of the duty is often debated. For instance, you could argue that the employer has the claim-right that you do a certain amount of work based on the contract and you have the duty to do that work. Anyway, claim-right is critical to understand the relation between the citizen and the government as well. Take taxes as an example. The government has the claim-right to collect taxes from citizens to fund its work. The citizen bears the duty to pay taxes.

Privileges and Claims are often called the primary rules in Hohfeldian analysis. They define what activities can or cannot be performed by individuals. Power and Immunity are the secondary rules which explain how someone can change the primary rules.

Power: Power allows an individual to change his own or someone else’s primary rules (privilege or claim). So, the CEO of a firm may order someone to work on a weekend afternoon and take away the privilege of sleeping. Or, your friend may waive the claim that you do not drive away with his car by allowing you to borrow it during the weekend. This waiver endows you with a privilege that you otherwise didn’t have.

Immunity: When you don’t have the power to change someone else’s primary rules, then that person has immunity. For example, you have immunity from the Indian state forcing you to change your religion.

Opposites and Correlatives:

What Hohfeld did following this was to arrange these incidents in a logical structure of “opposites” and “correlatives”. He also added a few other terms: ‘no-claim’ which is the opposite of claim; and, ‘liability’ and ‘disability’ that correlate with someone having power or immunity respectively. In a simple form this can be shown as:

Opposites

If A has a Claim, then A lacks a No-claim

If A has a Privilege, then A lacks a Duty

If A has a Power, then A lacks a Disability

If A has an Immunity, then A lacks a Liability.

Correlatives

If A has a Claim, then some person B has a Duty

If A has a Privilege, then some person B has a No-claim

If A has a Power, then some person B has a Liability

If A has an Immunity, then some person B has a Disability.

As stated here:

A privilege is the opposite of a duty; a no-right is the opposite of a right. A disability is the opposite of a power; an immunity is the opposite of a liability.

‘Correlatives’ signifies that these interests exist on opposing sides of a pair of persons involved in a legal relationship. If someone has a right, it exists with respect to someone else who has a duty. If someone has a privilege, it exists with respect to someone else who has no-right. If someone has a power, it exists with respect to someone else who has a liability. If someone has an immunity, it exists with respect to someone else who has a disability.

A right can be enforced by a lawsuit against the person who has the correlative duty. A privilege negates that right and duty, and typically would be asserted as an affirmative defense in the lawsuit. A power is the capacity to create or change a legal relationship.

Simply put, there’s an interplay between rights and duties but in no circumstance are rights and duties ‘two sides of the same coin’ or ‘upholding of duties lead to a downstream privilege of enjoying rights’.

Our Civilisation Is No Exception

Lastly, there’s always a call to some kind of civilisational value among Indians where we apparently held our duty above everything else. The idea of maryada purushottam or various kinds of dharma - saadharan dharma, vishesh dharma and swadharma - are invoked to suggest we placed the adherence to our duties as the highest form of self-realisation and as the basis for organising our lives. Is this true? There’s, of course, the usual challenge of understanding the context of Indian scriptures. These concepts are variously described with a lack of coherence because what we are left with fragments of metatexts with no clear interpretation of why and how these ideas have come about. As commonly understood, dharma is about doing the right thing. A simple definition is that it is a code of doing the right things at a universal level that ‘holds all of us together’. It is a necessary condition for a functioning society but is it ontologically prior to individual rights? It is not clear. The fact that dharma is invoked to hold us together already presupposes we are together in some form. And it can be argued that coming together can only be on the basis of respecting the individual rights of one another in the first place. On that, we must have built an architecture of dharma to make sure public-spiritedness and working for the collective is codified in our way of life. In some ways, I can agree we might have figured out Hohfeldian logic in our scriptures much earlier than the West. But it is a far stretch to claim some kind of exceptionalism about being a society where duties came before rights.

The Emphasis On Duty

The reason I get anxious when I hear the discourse on duties is that it has a terrible past. Even in India, the founding fathers and mothers in all their wisdom didn’t include the idea of duties in our constitution. The bizarre idea of fundamental duties was included in the Constitution by Indira Gandhi during the Emergency through the 42nd amendment. There it has remained since. And it isn’t as if the post-enlightenment thinkers weren’t taken in by the idea of duties. Mazzini, whose thoughts and essays were instrumental in the creation of the Italian state, wrote about duties extensively. The exhortation to a people to think of themselves as different and better than that of the other and begetting proto-nationalism in the late 19th century Europe were his key contributions. Sample this:

…. Wherever you may be, into the midst of whatever people you have been driven by circumstances, fight for the liberty of that people if the moment calls for it; but fight as Italians, so that the blood which you shed may win honor and love, not for you only, but for your Country. And may the constant thought of your soul be for Italy, may all the acts of your life be worthy of her, and may the standard beneath which you range yourselves to work for Humanity be Italy's. Do not say I; say we. Be every one of you an incarnation of your Country, and feel himself and make himself responsible for his fellow-countrymen; let each one of you learn to act in such a way that in him men shall respect and love his Country.

Your Country is one and indivisible. As the members of a family cannot rejoice at the common table if one of their number is far away, snatched from the affection of his brothers, so you should have no joy or repose as long as a portion of the territory upon which your language is spoken is separated from the Nation.

As you will notice, while Mazzini begins his famous essay The Duties of Man (1844-58) by claiming the first duty of man is to humanity, he gradually sinks into ideas that had terrible consequences for humanity half a century later in the form of two world wars.

There’s a reason why there have been no recorded instance in history when people have agitated for their duties. All uprisings and rebellions are about the fights for rights. People understand their duties both intuitively and as part of the social compact. It is part of traditions in communities. Rights are often trampled in the name of duty by establishment and authoritarian figures to perpetuate power. There are temporary occasions when an overemphasis on duties is valid. During a war (like that Kennedy line on country during the peak of the cold war) or during an internal crisis (Gandhi often invoked it). But those exceptions aside, it is otherwise brought in by establishment to explain underperformance or to shift the blame on to citizens from the shoulders of the state.

It is equivalent to gaslighting the citizens in a democracy.

India Policy Watch #2: Buy Now Pay Later ft. Government

Insights on burning policy issues in India

- Pranay Kotasthane

The finance minister will present the union budget in Parliament next week. A related news item flagging the rising debt commitments caught my attention:

"Interest burden is likely to stay around Rs 9.30 lakh crore for FY23," a finance ministry official told ET.

This is an increase of 15 percent on the Rs 8.1 lakh crore which has been budgeted for interest payments in the current fiscal. The amount is also 16.9 percent higher than the revised estimate for FY21.”

If government finances don’t interest you, these numbers may sound meaninglessly large. Nevertheless, let me try and explain why you should care.

To the question “what is the single largest expenditure item of the union government?”, the two most common answers I get are defence or salaries. Both answers are wrong.

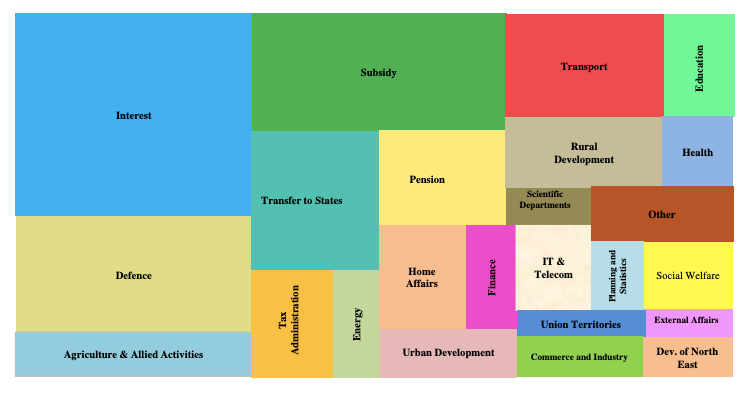

The biggest expenditure item is the interest paid by the union government to borrowers on past loans. The chart below from the previous year’s budget tells us that roughly a fifth of the government’s total expenditure is being spent on interest payments.

The news report from earlier this week suggests that this interest payment is set to increase further this year. The single most important reason we should care is because of intergenerational inequity — the more that governments live beyond their present means today, the less money they leave for future governments and citizens to decide their own spending priorities. That’s what a real debt-trap looks like.

Of course, many governments across the world run deficits and the Indian government is not an exception. Most often, governments take loans to finance physical and social infrastructure. If that is the case, intergenerational inequity is mitigated to the extent that the outputs continue to be used by future generations.

However, that is not the case in India. The union government still runs a sizable revenue deficit, meaning that a part of government borrowing is being used merely to keep the government running today. In other words, we are snatching money from future generations to meet the demands of the current generation’s citizens and government employees. This tells us why the rampant expansion of government expenditure is not just irresponsible but also unethical.

I’ll end this section with a quote by Martin Feldstein from his LK Jha Memorial Lecture at RBI:

“Unfortunately, it is easy to ignore budget deficits and postpone dealing with them because the adverse effects of budget deficits are rarely immediate. Fiscal deficits are like obesity. You can see your weight rising on the scale and notice that your clothing size is increasing, but there is no sense of urgency in dealing with the problem. That is so even though the long-term consequences of being overweight include an increased risk of a sudden heart attack as well as of various chronic conditions like diabetes. Like obesity, government deficits are the result of too much self-indulgent living as the government spends more than it collects in taxes. And, also like obesity, the more severe the problem, the harder it is to correct: the overweight man has a harder time doing the exercise that could reduce his weight and the economy with a large deficit and debt is trapped by increasing interest payments that cause the deficit and debt to rise more quickly. I emphasize the analogy to stress the point that budget deficits need attention now even when their adverse effects may not be obvious.”

India Policy Watch #3: The Great Indian Exit

Insights on burning policy issues in India

- Pranay Kotasthane

India has long been a leading outlier as a source for out-migration. Further, thanks to a Lok Sabha question in December 2021, we know that more than 1 lakh people have been renouncing their Indian citizenship every year over the last several years.

Emigration is an important consideration if not an important life goal for many Indians. At one end of the income spectrum, it is a ticket out of poverty. On the other end, it leads to a step-up in one’s quality of life.

But how should we see emigration from the lens of public policy? Beyond facile “brain drain vs brain gain” discussions, how do we understand the impact of emigration on India?

Let’s establish the boundary conditions first. Because emigration is a voluntary act by an individual, it is a force of immense good. As emigration is one of the partial answers for achieving yogakshemah, the Indian State must make it easier for Indians who want to leave India. There is no justification in a liberal democracy for moralising Indians on staying back just because, for instance, they received subsidised education in a government college.

Going beyond individual choices, what’s the aggregate effect of emigration on India? Turns out, there’s no good empirical answer. While states generally pay close attention to immigrants, the country of origin has little incentive to keep track of the lifecycle of emigration. Consequently, this area of research is not exactly a gold mine. And so, for the last comprehensive assessment of India’s emigration, we have to turn to a 2010 book Diaspora, Development, and Democracy: The Domestic Impact of International Migration from India by well-known political scientist Devesh Kapur. Given below is my annotated summary of the book.

Kapur remarks that:

“one cannot a priori posit whether international migration is “good” or “bad” for a country. The outcomes depend heavily on the policies of the country of origin—which of course can (and do) change over time.”

Coming to India’s case, he contends that the economic effects of emigration have been mixed while the political effects of emigration are largely positive.

The Economic Impact of Emigration

Let’s take the economic effects first. The migration of less-skilled labour to West Asia has had a positive effect not just for those who emigrated but also for those who were left behind as the decrease in labour supply has led to more domestic migration and rising wages. Further, incoming remittances have played a big role in stabilising India’s macroeconomic situation.

In contrast, the economic effects of the emigration of high-skilled labour to the West are more ambiguous. On the positive side, the success of these Indians has improved the reputation of India and Indians worldwide. Moreover, some of them have acted as bridges for the flow of ideas, technologies, and information back to India. On the negative side, the exit of professionals has contributed to making institutions that were globally competitive at the time of independence, mediocre organisations with low ambition and drive.

Kapur also suggests a reason as to why the famed Indian diaspora has not been able to make India a manufacturing hub:

“India’s economically successful diaspora has developed a comparative advantage in white-collar skilled services such as information technology (IT) and tertiary medical services. Consequently, the investments they have influenced into India have also been in these sectors, rather than blue-collar labor-intensive manufacturing sectors (the diamond industry is an exception).

The Indian example illustrates a broader point about how the sectoral expertise acquired by emigrants overseas diffuses back to the country of origin. Parallels can be draw with the Chinese example, where the economically successful Chinese diaspora (especially in Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, and Taiwan) made its wealth (and acquired relevant capabilities) in labor-intensive manufacturing, and therefore its investments into China were in related sectors as well.”

The Political Impact of Emigration

The political effects of emigration, Kapur argues, are positive in two ways.

One, returning emigres and international exposure have helped in strengthening the commitment to liberal democratic politics. Twelve years after the book was published, this claim appears weaker. Liberal democratic politics in the west itself has been battered. Moreover, the role of the Indian diaspora in furthering majoritarian anti-liberal politics has grown at a much faster rate than its antidote.

Two, Kapur suggests that the exit possibilities of emigration served an important social function. It acted as a pressure relief valve for the dominant upper-caste elites, making them less opposed to the political ascendancy of the marginalised social groups. In the absence of emigration opportunities, the contestation over job reservations and education quotas would’ve been much sharper. Here again, with the benefit of hindsight, we can say that the possibility of emigration hasn’t been an entirely effective pressure-releasing mechanism, as evidenced by the new legislation for reservations to economically backward but upper-caste sections.

The book’s conclusion resonated with me. Ultimately, where diasporas become sources of power or areas of weaknesses principally depends on domestic policy and politics.

First, forty years of socialist thinking, directly and indirectly, made emigrants distant. Illustrating this point, Kapur writes:

“In those years, when the Indian community was thrown out of East Africa, socialist India pressed the United Kingdom to admit them, seeing little benefit in attracting the community’s commercial skills and capital back to India. And when the British government finally gave in to pressure from India, it was seen as a major foreign policy achievement.”

Second, poor policy and business environments continue to make India less lucrative for emigrants:

“The well-known infrastructural and policy weaknesses in manufacturing have steered the diaspora’s role in IT more toward the software side, rather than developing the hardware sector. The decades of migration from Kerala have made it a remittance dependent economy, but one that has been unable to capitalize on this any further because of political and policy constraints in the state.”

And third, while India and Indians love to celebrate its emigrants who make it big in other countries, it does not allow the same opportunities for its immigrants.

In short, emigration from India does have a few negative political and economic effects. But mitigating these effects ultimately requires doing the tough job of improving the domestic social, economic, and business environment. There’s no shortcut.

Matsyanyaaya: Who’s Arm-twisting Whom?

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

— Pranay Kotasthane

(Cross-posted from Technopolitik — Takshashila Institution’s High Tech Geopolitics Newsletter)

This story has it all: geopolitics, anti-trust, national pride, future of technology, and capital markets.

The Prelude

ARM (mentioned as “Arm” from here on) licenses its CPU designs to customers such as Apple, Qualcomm, Nvidia, and MediaTek. For a long time, it has been trying to break into the data centre CPU market, dominated by Intel and AMD’s x86 designs. Despite an impressive list of customers, Arm’s financial fortunes haven’t been great — revenues through licensing fees and royalties have been on the decline since 2016.

Even though Arm is the sole supplier for mobile companies, why would this happen? Primarily due to four reasons. First, the mobile phone market is already saturating. Second, customers such as Broadcom, Qualcomm, Microsoft, Samsung, and Apple have an expansive Arm architecture license (as against implementation licenses), allowing them to design their customised Arm-compatible processors. So, Arm has little leverage over the sales from these companies. Third, Arm’s big bet on another market — datacentres — hasn’t worked out. And fourth, Arm cannot increase its license fee to compensate for sagging revenues because it faces a new challenge in the form of RISC-V technology.

The Players

In September 2020, Nvidia announced a deal to buy Arm. Since then, Nvidia’s shares have almost doubled. But after months of being blocked by four regulators — in China, the US, the EU, and the UK — reports suggest that Nvidia is planning to abandon the deal.

Let’s have a look at all the perspectives first.

In the US, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is opposing the deal because the deal would “distort Arm’s incentives in chip markets and allow the combined firm to unfairly undermine Nvidia’s rivals.” Unsurprisingly, many high-flying competitors of Nvidia such as Qualcomm and Intel are staunchly opposed to this deal as they feel Nvidia might partially delay or block their access to Arm CPU blueprints. The EU antitrust regulators also have similar objections to the deal.

In contrast, the dominant narrative in the UK is that the deal would hurt national pride. In ordinary times, such a narrative wouldn’t have carried far. But when the entire world looks at semiconductors from a strategic lens, this view has policy relevance. So, even though Arm is already owned and controlled by a Japanese investment firm, Softbank, the UK has renewed calls to list it back on the London Stock Exchange.

Next, Arm and Nvidia’s joint submission to the UK’s Competition & Markets Authority (CMA) comprehensively captures the two companies' viewpoints. Their main argument is that Arm faces an uncertain future without a takeover. The submission explicitly says:

Deal opponents romanticize Arm’s past and either ignore or disparage Arm’s most powerful competition. But if Arm had market power, it would have sizable revenue growth and would be enormously profitable.

The submission further claims why this deal would increase competition instead of reducing it.

For China, the concerns are entirely different. This deal would mean a more potent lever in the hands of the US to constrain China’s semiconductor sector. The US has already demonstrated that it could deploy wide-ranging export controls to block access to chips to geopolitical adversaries. With Nvidia controlling Arm, China fears that the US can easily prohibit Arm from selling to Chinese customers. As a result, China has been staunchly opposing this deal.

To be sure, the US can still pressurise Arm to not sell to customers in the absence of a deal. Just like it prevented the Dutch semiconductor manufacturing equipment star ASML from selling cutting-edge Extreme Ultra-Violet lithography machines to Chinese companies. Nevertheless, getting the UK — for whom this has become a national pride issue — to comply with such restrictions is far more complicated.

The Result

The deal opponents have their unique reasons. There’s no concrete evidence to suggest that the opponents are collaborating. Regardless, the net geopolitical effect is that China would be immensely relieved if the deal fails. At the same time, China would want to get RISC-V further up to speed with Arm so that this geopolitical weakness is taken out of the question over the long term.

#156 The Republic Of Our Future