“The architect’s role is to fight for a better world, where he can produce an architecture that serves everyone…” —Oscar Niemeyer

Hi everyone—I’m so glad to have you here. What a week.

I read the book Structures: Or Why Things Don’t Fall Down awhile back after it was recommended to me by an engineer. It turned out to be a master class in mental models that proved relevant to the world of finance too. Things like:

Why compression forces are more durable than tensile forces

The corrupting power of deformation and irregularities

That fatigue occurs when a heaviness is applied with varying intensity, causing fluctuations

The Physics of Wall Street is another book that actually documents the various insights from the physical domain that have been successfully (and unsuccessfully) applied to the world of money, trade, and commerce.

Just this week I heard this analogy in a podcast episode about investing and economic policy:

“There's this tower of blocks in your living room, and once you're a couple blocks high you can stomp on the floor and it still holds together. But once you're 16 layers up the smallest stomp causes the whole thing to crumble.

Basis points are moving markets, and when you go back to the days of [former Federal Reserve Chair Paul] Volcker the amount of latitude they had in that day and age is totally dissimilar to where we are today.”

And Max Keiser used a similar comparison to describe the fragility of America’s current economic situation in a recent conversation about nations trying to avoid falling victim to dollar hegemony:

“Is it really about leapfrogging or is it more about stepping away from a falling, collapsing building and surviving? The US dollar is in serious trouble, and the US economy is in serious trouble…”

Why are people so drawn to this metaphor? I think it’s because this whole finance thing is about structural integrity. Which is directly related to actual integrity.

When building something you want to make it level, but interestingly enough the word that contractors and architects actually use is “true.”

Most people involved in finance at the federal level not only don’t know what’s true in the structure they’re responsible for overseeing, they don’t actually know much about it at all. They don’t even know, or care, where money itself comes from.

In this painful but hilarious clip, Canadian MP Pierre Poilievre asks the simple question, “How is the government paying for this $7 billion bill associated with this proposal?” and is met with nearly 5 minutes of silence and bumbly nothingspeak.

He asks again, “Where is the money coming from?”

…🦗 …🦗 …🦗

“Well, somebody’s paying for it. Who is it?”

…🦗 …🦗 …🦗

“Is it the tooth fairy?”

…🦗 …🦗 …🦗

“No answer. How many witnesses do we have here? 10 witnesses. 10 witnesses to tell us how to spend money, but not a single one to tell us where the money comes from.”

And this, my friends, is a glimpse at the foundation supporting all the stocks, bonds, derivatives, payrolls, and pensions in society. This fiat-based financial system isn’t even built on quicksand or loose gravel, it’s built on… nothing.

A few months ago Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau actually went on record to say, “I don't think about monetary policy,” so it makes sense that all other underlings and ancillary government officials won’t be held accountable for caring about such trivial details as “where money comes from” either.

This is a problem because most of the issues being talked about are actually a consequence of the cascading ripple effects of the monetary policy. It’s on top of the monetary policy foundation that calculations regarding profit, loss, tradeoff, value, and cost are being built. Decisions—monumental ones—are being made using these figures.

There are very deep reasons why those who make decisions, especially regarding something as foundational as money and economics, should be held accountable for all the consequences resulting from those decisions. In fact, almost 4,000 years ago King Hammurabi of Babylon, Mesopotamia, laid out a set of laws that did exactly this.

Hammurabi’s Code is among the oldest translatable writings. It consists of 282 laws that mostly regard punishment and consequences, each taking into account the perpetrator’s status. It’s essentially a document about managing risk.

It also contains the earliest known construction laws, designed to align the incentives of builder and occupant to ensure that builders created safe homes. Check out Law 229:

If a builder builds a house for a man and does not make its construction firm, and the house which he has built collapses and causes the death of the owner of the house, that builder shall be put to death.

A harsh sentence to be sure, but it communicates certain core values that extended to many of Hammurabi’s other laws: the importance of reciprocity, accountability, and incentives.

What we have today are builders of monetary policy who are not held accountable for negative consequences, and are therefore completely unmoored from any sense of social contract, ethical framework, or responsibility.

Without being held accountable for consequences arising from an individual’s decisions there is nothing to incentivize good behavior or quality decision-making. Dialogue and lengthy tradeoff assessments become entirely pointless.

It’s no coincidence that we refer to it as paying the consequences. Value exchange and monetary systems are about ensuring balanced exchange—things must be paid for. It’s as much a principle of trade as it is of physics: matter cannot be created or destroyed, it can merely be (ex)changed.

Structural integrity is about building something in such a way that it can be trusted—building something true. If you can’t even trust the monetary system on top of which everything is built, then what you have is a dangerous structure that poses a threat to all those who use it.

So when the US decides to allow itself the continuous privilege of extending its line of credit, this time to the tune of an extra $2,000,000,000,000, it’s a real problem for the rest of us. It’s like using your Mastercard to pay your Visa bill. Doing this expands the money supply, leading to (by definition) higher inflation of the money supply, and interest rates that are distorted to reflect artificial manipulation and not the behavior of actual market participants.

How are you supposed to do any economic calculation whatsoever with such amorphous and inconsistent units of measurement?

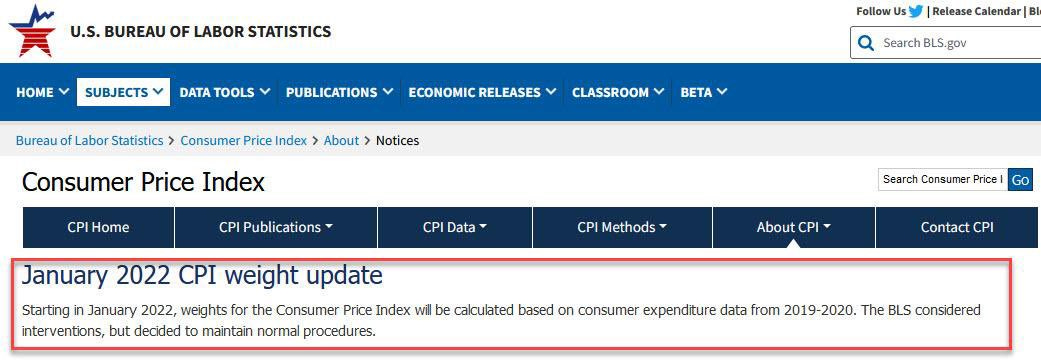

Here’s an example of the type of distortion I’m talking about: the Bureau of Labor Statistics has just decided to change (again) the weighting of the basket of goods used to calculate the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”) to be based only on the things people spent money on in 2019. i.e. They're setting a new baseline to hide the amount of price inflation that has actually occurred.

The CPI is the number the government cites as a proxy for the inflation rate. So why would they change what’s included in that inflation calculation?

Well, because people's spending habits changed after the pandemic in 2020 and now those changes won't be accounted for. Less demand for those goods means their prices will be lower now, which will keep the CPI number low. So this lets the government make it look like inflation is not as bad as it really is. (Home prices used to be included in the CPI calculation back in the day. Take a guess as to why they decided not to track that one anymore either…)

On Friday it was announced that the CPI rose to 6.8% year over year—the highest since 1982. The US has now experienced six months of over 5% inflation with prices rising across the board including such staples as gas, food, new & used cars, and housing (rents). But that 6.8% is the understated number they’ve created to look as good as possible. Real inflation is much higher. I’d double that 6.8% for a more accurate idea of how much purchasing power your cash is losing every year.

By allowing central bankers and policy makers to distort statistics, add (or remove) currency from the system at will, and favor certain goods and services over others, they create a economic foundation full of cracks and without the integrity to function as a system that can last or be trusted at all.

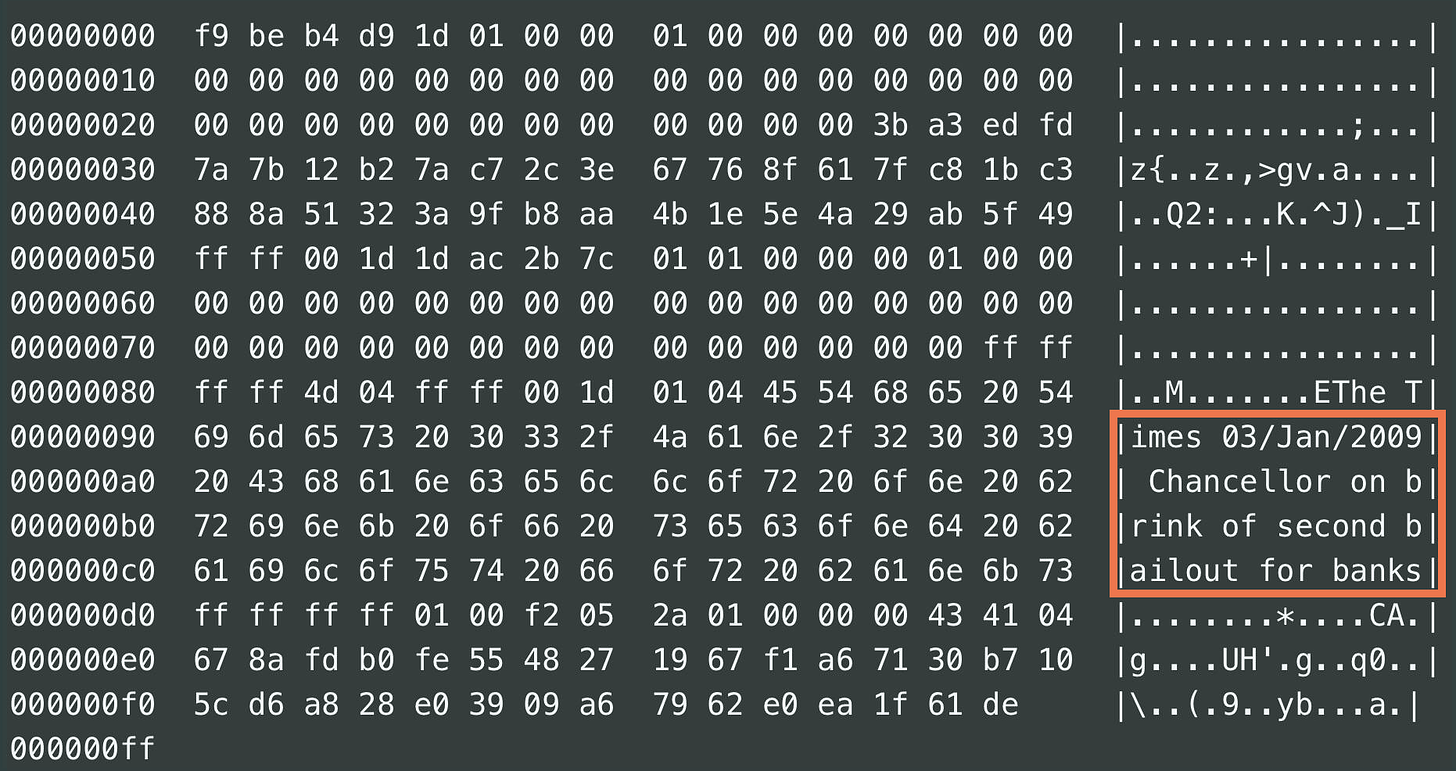

This is the problem that Bitcoin was invented to solve.

Satoshi Nakamoto made sure this would not be lost on anyone when he included a very specific Times headline in the coinbase parameter of the very first block of transactions ever mined, a nod to government response at the time to the global financial crisis:

The idea was to turn monetary policy into a fixed, censorship resistant, decentralized protocol of rules, not a malleable set of constantly changing guidelines manipulated by an increasingly irresponsible series of rulers. Much like Hammurabi’s Code which was etched into stone.

At this point it might not come as much of a surprise that some of earliest proponents of Bitcoin from the traditional finance sector all happen to have a background in engineering: Lyn Alden (macroeconomist), Greg Foss (former bond trader), Preston Pysh (value investor and creator of the We Study Billionaires podcast network), Michael Saylor (CEO of Microstrategy), and Saifedean Ammous (economist and author of The Bitcoin Standard).

"Most people are problem identifiers, not problem solvers. And as an engineer you have to solve the problem."

—Preston Pysh

Engineers try to quickly identify and focus on what’s known as the critical variable—the part of an equation that is key to getting to the solution. It turns out the critical variable in an economy is the money… which should really function closer to being a constant in the equation and not something that varies at all.

Bitcoin is a thermodynamically sound system whose tokens exist inside a closed, self-correcting, balanced, adiabatic system. This structure matters, and the checks-and-balance relationship between nodes and miners is part of what keeps the system honest, reliable, trustworthy, and hard.

Sadly, what began as a separation of banks and state has become a cozy and self-reinforcing relationship between one single centralized bank—the cartel of unelected bankers known as The Federal Reserve—and the United States Treasury. The two are now in cahoots, not so much keeping each other in check as cooperating in concert at the expense of everyone downstream of their decisions.

“I don't believe we shall ever have a good money again before we take the thing out of the hands of government… We cannot take it violently out of the hands of government, all we can do is by some sly roundabout way introduce something that they can't stop”

So long as this corrupt alliance continues we can expect more fragility, instability, and fractured foundations at the base of society. It won’t be until we begin using a trustworthy alternative to central banking that the integrity of society has any hope of strengthening.

Otherwise, we all fall down.

Until next time 🤙,

Recommended Resources For Plan ₿

Swan. I became an official Swan partner because I love them so much. So if you're like me and just want an easy, automated way to buy bitcoin on the regular with the lowest fees in the game, head to https://swanbitcoin.com/Mulvey to get $10 in bitcoin for free ✨

Fold Card. Earn bitcoin on everything. You can win up to 100% back on every purchase, and every swipe is a chance to win a whole bitcoin. I use my own Fold card to pay for almost literally everything. If you use this referral link you get 5,000 sats free ✨

Surf Report: Structural Integrity