Global Policy Watch: Who’s Afraid Of Stakeholder Capitalism?

Insights on global issues of the day

- RSJ

Sometime in late 2019, Alan Jope, chief executive of Unilever, the global food and cosmetics giant, declared that brands without an evangelical purpose of contributing to society will soon face extinction. As the Guardian reported then:

Alan Jope, Unilever’s chief executive, said it was no longer enough for consumer goods companies to sell washing powders that make shirts whiter or shampoos that make hair shinier because consumers wanted to buy brands that have a “purpose” too.

“Can these brands figure out how to make society or the planet better in a way that lasts for decades?” said Jope, outlining the company’s thinking. Unilever is not working to a set timetable but Jope, who took over from Paul Polman in January, said it was possible that a brand or even whole product category “is not going to be able to find its purpose”.

His comments raised the possibility of the company selling off profitable brands, potentially hurting the bottom line, but Jope said: “Principles are only principles if they cost you something.”

This looked good. I mean we all want businesses to have more social responsibility. Here was a CEO willing to take a long view of what’s good for society and let go of short-term gains.

How are things going for Alan Jope now? Well, here’s Nils Prately writing in the Guardian last week:

Unilever is frustrating its shareholders. Last year’s stock market “rally in everything” bypassed the consumer goods giant entirely. The shares fell by a tenth and, at £39.42, stand roughly at their level of five years ago, soon after the group adopted a supposedly energising cost-cutting and deal-making overhaul in response to its close encounter with Kraft Heinz’s financial engineers.

Perhaps, the most entertaining rebuke came from fund manager Terry Smith:

“Unilever seems to be labouring under the weight of a management which is obsessed with publicly displaying sustainability credentials at the expense of focusing on the fundamentals of the business.

A company which feels it has to define the purpose of Hellmann’s mayonnaise has in our view clearly lost the plot. The Hellmann’s brand has existed since 1913 so we would guess that by now consumers have figured out its purpose (spoiler alert – salads and sandwiches).”

Heh!

But this isn’t an isolated instance of a corporation grandstanding on contribution to society as its purpose. And a lot of it is driven by other shareholders who value it more than, say, Terry Smith above. For instance, Blackrock, the world’s biggest investment manager, that owns like seven percent of every public company out there, has made ESG (environmental, social and governance) metrics a priority for their investment decisions. Over the last few years, Larry Fink, the chief executive of Blackrock, has emerged as the most influential voice on the role of business in driving the sustainability agenda. This has meant Blackrock cutting back its investments in enterprises that are seen to be bad for environment and sustainability. But this has not been without a backlash. The Republicans and their supporters see this another sign of ‘wokeism’ dominating business agenda. The more left leaning wing of Democratic party feel this is all lip service and Blackrock is not doing enough to push sustainability. There’s also the usual chorus about should it be elected lawmakers who must drive this or an unelected powerful businessman regardless of their good intentions? Plus, there’s been the usual unintended consequences. The throttling of investments into thousands of firms that have business models that still leech off environment while being hugely profitable has increased the spreads on their bonds giving an opportunity to other investors to profit. Also, with so much investments going into ESG, some sort of a ‘green asset bubble’ has been formed with businesses of all stripes positioning themselves as green and sustainable to free ride into billion-dollar valuations. These things usually end up badly for everyone.

So, in his latest annual letter to CEOs titled ‘The Power of Capitalism’, Larry Fink seems to suggest he’s moderating things a bit. He starts off in the usual fashion defending the focus on stakeholder capitalism (i.e., thinking beyond shareholder profits):

Stakeholder capitalism is not about politics. It is not a social or ideological agenda. It is not “woke.” It is capitalism, driven by mutually beneficial relationships between you and the employees, customers, suppliers, and communities your company relies on to prosper. This is the power of capitalism.

He continues with his call for net-zero goals and finding a purpose beyond profits but there’s a subtle shift in tone:

In today’s globally interconnected world, a company must create value for and be valued by its full range of stakeholders in order to deliver long-term value for its shareholders. It is through effective stakeholder capitalism that capital is efficiently allocated, companies achieve durable profitability, and value is created and sustained over the long-term. Make no mistake, the fair pursuit of profit is still what animates markets; and long-term profitability is the measure by which markets will ultimately determine your company’s success.

Purpose Of Capital

We talk about the role of capital often here. What purpose must it serve in society? How should policies be drafted to channel it for all round, sustainable progress? These aren’t new questions. Adam Smith mulled over it. Marx wrote a whole book thinking about it in ways that were original and revolutionary. That they were fundamentally unsound is a different thing. Unpaid labour is not the source of surplus value in capitalism, like he thought. There was a pause in thinking about capital in a deeper way during the first half of the 20th century. The two world wars and the great depression created the field of macroeconomics that concerned itself with questions of managing the national economy. The early Austrian school economists went the other way in thinking about the micro - a rational individual, her utility from a product or a service and her actions to maximise it. While economic thought about the nature of a firm was around during that time, most notably in the works of Ronald Coase, it wasn’t mainstream. Only in the 60s when American capitalism produced a boom rarely seen before in history did economists turn their attention to the nature of wealth creation in society and its purpose. Of course, the most famous of the economists among them was Milton Friedman.

We have written about Friedman before. After a lot of soul searching, Friedman concluded:

“But the doctrine of “social responsibility” taken seriously would extend the scope of the political mechanism to every human activity. It does not differ in philosophy from the most explicitly collectivist doctrine. It differs only by professing to believe that collectivist ends can be attained without collectivist means. That is why, in my book “Capitalism and Freedom,” I have called it a “fundamentally subversive doctrine” in a free society, and have said that in such a society, there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception fraud.”

The role of any business is to maximize shareholder value in a legal way. That’s it. Everything else can be counted as good intentions but will have unanticipated consequences. Shareholder value maximisation, on the other hand, checks all the boxes of a good metric for three reasons.

A simple and measurable metric: The shareholder value maximisation goal is easy to set and monitor. It helps that there is a common understanding of the metric. The alternatives are amorphous. It is difficult to understand what does maximising societal value entail, for instance. Who will define what society wants? Are societal objectives of India and the US similar?

Rewarding the risk-takers: The shareholders invest risk capital in an enterprise. This willingness to take risk is what leads entrepreneurs to build new products, satisfy the consumers and create new jobs. The shareholders deserve the pursuit of maximum return by the firms for this risk they undertake. It is up to them what they do with these returns. They can invest it in newer enterprises or use it to improve society as they deem fit. The management or anyone else should have no claim on how to invest the returns that belong to the shareholders.

Shareholders are the residual claimants: Everyone who contributes to the value creation of an enterprise – the employees, the management team and the customers – get their fixed claim on the value through compensation for their efforts, stock options and the value derived from the products or services offered by the enterprise. Whatever is left is for the shareholder. Only when these fixed claimants are served well, the value for the residual claimant (the shareholder) is maximised. So, the pursuit of shareholder value will by itself serve the other stakeholders well.

Doing One Thing Well

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) wasn’t good for the Friedman doctrine. The massive ‘financialisation’ of business, the loosely regulated nature of financial markets which allowed for the excesses and the bailouts which saved those who had brought about the crisis were seen to be a product of Friedman’s profit maximisation philosophy. Since then controlling free markets and unbridled capitalism as ideas have found favour in most capitalistic societies. More so among the young. And in the last few years, we have had ESG added into the mix. Corporations are now supposed to do things that will serve the interest of the environment and sustainability in the long run. It sounds good and who can argue with it. But like all good intentions, it is hard to implement and runs the risk of doing just the opposite.

One, beyond profit maximisation, the shareholders will have heterogenous objectives and time horizons for their investment. The definition of what’s good for humanity will be amorphous among them. Should a company increase its costs of production by adopting ‘green’ practices and make losses in the next five years in the hope that it will eventually make more profits in the long run because of this shift? Will all shareholders reward the management for this? Seems quite unlikely. Some shareholders will have shorter time horizons. Others will disagree on what’s truly ‘green’ and a few might even ask if climate change is for real.

Two, the management which is the agent of the shareholders running the business has an incentive to have shareholders with ambiguous objectives. The classic management defence for short-term underperformance is we are building things for the long run. Nothing is more long-run than saving the earth seen from the perspective of the management annual performance cycle. The more ESG pressure that shareholders bring about on the management, the easier it is for them to include the long-term indeterminate objective of saving the earth in explaining their decisions and performance. There is already a danger that a lot of management teams have embraced this notion of purpose (like for mayonnaise) for performative reasons. They know talking ESG is good for the stock in the short term. Or, there is an incentive to explain away their lack of near-term performance to the pivot of being ESG friendly. Neither is good for society.

Three, the core management problem in an enterprise is how to allocate capital among the many competing priorities in an enterprise. This is a prioritisation problem that takes a lot of skills to get right - understanding the financial returns of different products and markets, anticipation trends in consumer behaviour, figuring out competitors and regulatory environment. Managers spend their careers learning to get this right. Most fail in the long run which is why corporate mortality is so high - maybe 10 companies or fewer have survived among the top 100 U.S. enterprises from about 50 years ago. Now to burden them with a variable that’s not just difficult to quantify or predict but also is freighted with political and personal beliefs will only make decision making more difficult. More likely than not they will get it wrong.

It is for these reasons Friedman’s doctrine remains the most elegant and practical way for firms to pursue its objectives that deliver the most value to society. For Friedman, enterprises in a competitive market pursuing shareholder maximisation will do well for society. The policymakers should work on frameworks that create the right incentives for shareholders and the management to do so while serving the long-term interests of the society. The management then works within it. It isn’t for the management or for the shareholders to optimise for objectives beyond that. The shareholders can take those returns and do what they believe is best for the society based on their beliefs. Somewhere in that Fink annual letter is a muted acceptance of this idea.

PolicyWTF: One Person, One Hand Bag

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

- RSJ

This caught my attention yesterday (from the Business Standard). Yes, there’s a guideline to enforce one handbag rule as cabin baggage in flights.

In a memo, BCAS (Bureau of Civil Airport Security - who knew there was this too?) said:

“It has been seen that an average passenger carries 2-3 hand bags to the screening point. This has led to increased clearance time as well as delays, congestion and inconvenience to passengers. It is, therefore, felt that enforcement of the aforesaid circulars must be ensured by all stakeholders,” it added.

Like those hold-all bags my family used to carry during rail travel in three-tier compartments, there’s a lot to unpack here.

Congestion has been a problem for long in Indian airports. In fact, the pandemic has meant lower congestion than usual. So, how did this problem and this solution present itself to the Bureau? Here’s the answer from the same report:

People aware of the development said a few parliamentarians had complained to Civil Aviation Minister Jyotiraditya Scindia regarding congestion at security checks. Following that, the regulator was asked to implement steps to ease congestion.

“We had a meeting with the representatives of airlines and have told them to impose the rule. It takes more time to clear multiple bags,” the security agency said.

Ah! Few parliamentarians complained. I’m unsure if they were held up because of congestion because there’s usually a separate VIP channel in all Indian airports. Maybe the number of VIPs have proliferated to such an extent now that there’s congestion in that queue too. It ain’t easy to be a VIP these days. Anyway, the solution that we have come up is two-fold. Quoting the report again:

“All airlines and airport operators may be instructed to take steps to implement ‘One Hand Bag rule’ meticulously on ground to ease out the congestion and other security concerns. Airlines may be made responsible and depute staff to guide passengers and check and verify their hand bag status before allowing the passenger for pre-embarkation security checks, “ the memo added.

And the second solution:

Besides, airlines were also asked to change flight timings so that too many flights don’t arrive or depart around the same time to prevent overcrowding at airports. However, the idea was dropped after airlines opposed this saying changing flight timings in between an ongoing schedule will not leave flexibility and force them to cancel flights, leading to chaos.

Thankfully, the second solution was dropped. On to the first solution about enforcing the one-bag rule strictly. So, what will people do? They will be forced to check in their luggage to comply with this. And that will mean the baggage check-in queues will be congested which takes even more time than the security check queue. This is the Indian flyover solution. Build a flyover to solve for congestion and soon realise the congestion hasn’t eased. It has only moved to another location.

What about the real solutions? Like thinking about better queue management processes, figuring out queuing patterns during different hours of the day and week based on data and planning capacity to manage the peaks or increasing the capacity for security checks - there’s not a word on these.

It is a chhota story. But it has everything that you need to know about public policy in India.

India Policy Watch: The Problem with Protectionism

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

Policy success, like beauty, lies in the eyes of the beholder. One such policy success that’s been talked about a lot of late is the increase in mobile phone production in India. The narrative underlying the success is that through a prudent mix of protectionism and industrial policy instruments, India has been able to reduce its mobile phone dependence on other countries, particularly China.

This deemed policy success is now being seen as the playbook for many other manufacturing sectors such as electric vehicles and pharmaceuticals. For instance, see this excerpt from Nilesh Shah and Pankaj Tibrewal’s article titled The mobile phone sector has lessons for India’s economy:

“We were one of the largest consumers of mobile phones in 2014. In 2014-15, our mobile phone imports exceeded $8 billion. Our electronics imports were threatening to exceed our oil imports. The government took many steps like 100 per cent automatic FDI, levy of import duties to protect local manufacturers, the Phased Manufacturing Plan (PMP), manufacturing clusters (EMC 2.0) and the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme. Despite some execution challenges on the ground, these steps have developed our mobile phone manufacturing base. They have attracted investments, created lakhs of jobs, and have moved us from being a net importer to a net exporter.

Our mobile phone manufacturing value has jumped more than eight times from Rs 0.27 trillion in 2013-14 to Rs 2.2 trillion in 2020-21. Samsung runs the world’s single-largest location mobile handset manufacturing plant in Uttar Pradesh. We have surpassed the US and South Korea to become the second-largest manufacturer globally.” [Indian Express, Jan 20]

Impressive, isn’t it?

By now, you already know there’s going to be a “but” somewhere. So here it is.

Judging a policy based only on the benefits it brings is possibly the most common mistake in policy discussions. To understand the complete picture, we also need to analyse the costs.

What about the Costs?

Of the policy instruments used, allowing 100 per cent FDI through the automatic route is an unequivocally positive step. And we have dealt at length with the promise and perils of the mushrooming PLI schemes in editions 86, 118, and 153.

In this edition, we will limit the discussion to the third instrument in the armour: increasing import tariffs.

The modus operandi seems to be somewhat like this. Through the Phased Manufacturing Program (PMP), the government increases import duties on final consumer products such as mobiles, chargers etc. This leads to import substitution because products assembled in India (even with imported parts) start to become cost-comparable to the duty-levied imports. Every year, the government keeps adding new products to this PMP list, with the objective of increasing the number of final goods that are assembled in India. The final aim and hope is that these assembly units will become the nuclei for a complete manufacturing ecosystem over time.

No, the costs of this strategy are being borne by two sets of Indians.

The first losers are all consumers. Higher import duties mean that mobile phone prices have been increasing. The absolute increase isn’t alarming at first sight, to be frank. But electronics prices commonly fall sharply with improving technology, and that has certainly not happened for phones over the last five years. Vivek Kaul has explained the cascading effect of this price rise here:

When an individual spends more on something, she cuts down on expenditure in some other area. Given this, if one business benefits due to protectionism, another business or other businesses, lose out in the process. It’s just that this is not so obvious in the first place and hence, is the unseen effect of protectionism.

Second, the Indian manufacturers themselves have been under the pump because of rising tariffs for mobile phone parts. The lure of protectionism is such that it quickly spreads from final products to intermediate inputs. Soon, it was felt that not just mobile phone makers but domestic manufacturers of camera modules and connectors should also be ‘protected’. The result — not surprisingly — the import duties are now negating all the benefits provided under the PLI schemes. Manufacturers are still unable to compete in export markets because the parts they import have become costlier. A recent comparative study analysing import tariff regimes of India, Thailand, Vietnam, China, and Mexico puts this well.

The main difference in their policy approach is the tariff policy of India compared to others. India has relied heavily on higher tariffs whereas other countries have not done so. Higher tariffs orient the approach of investors and domestic producers away from global markets and towards the domestic market. Notably the exports for India compared with others have remained low as has been examined in this report.

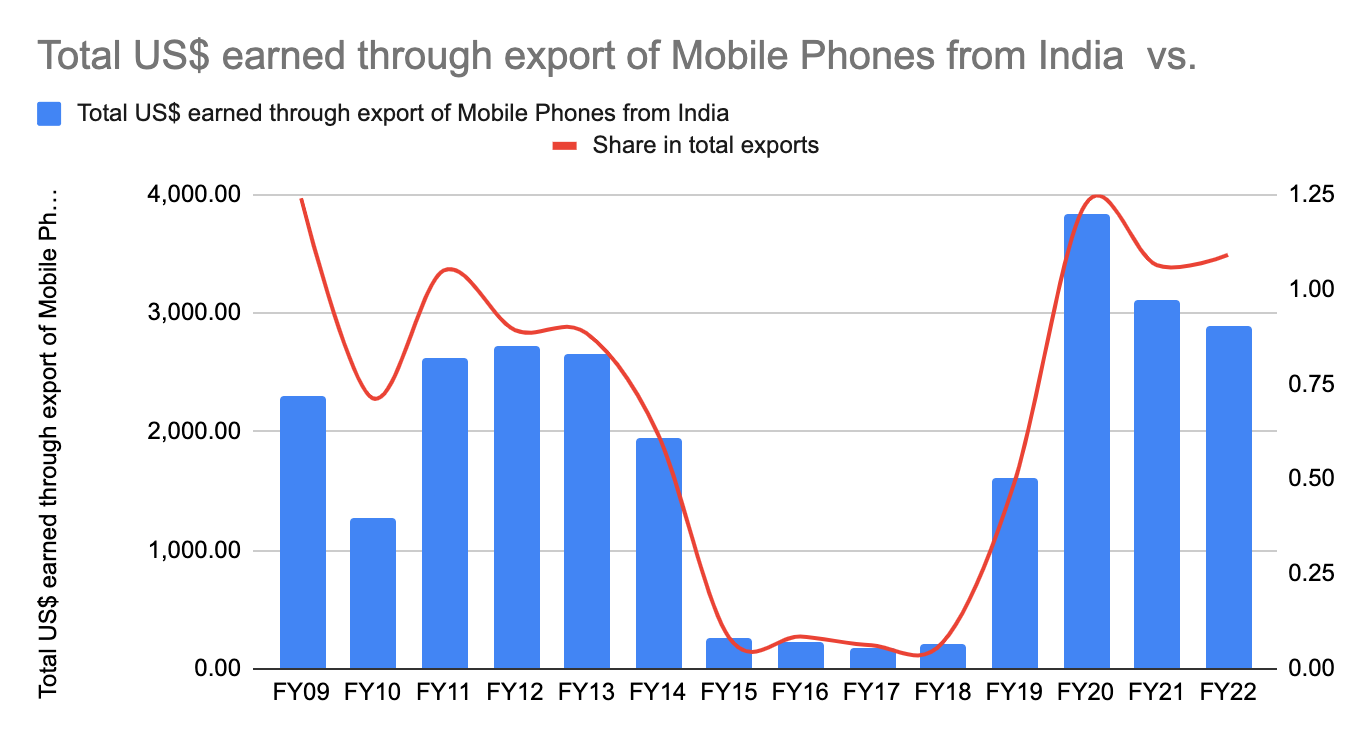

This is a crucial point. While the various incentives and protectionism has been successful to the extent that imports of phones have reduced, we are still far away from becoming a competitive exporter. Have a look at this chart I made from government data on mobile exports.

As you can see, India’s mobile phone exports fell sharply from FY15 to FY18 with increasing tariffs. Though exports in absolute terms have picked up in the last three years, mobile phones as a share of India’s total exports is still below what was achieved way back in FY09!

Going ahead, India’s domestic market alone (projected to be 8.8% of the global market in FY26) is insufficient to attract more manufacturing here. The ability to competitively export will be a key determinant of policy success going ahead. And for exports to rise, imports tariffs must be brought down.

In sum, before copying the mobile phone policy success playbook in other sectors, we must remember that the burden of protectionist policies is borne by the consumers and eventually the manufacturers, both. Protectionism can play spoilsport in India’s hopes of exporting its electric vehicles and mobile phones to the world.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Podcast] An insightful episode of All Things Policy with MR Sharan on his new book Last Among Equals: Power, Caste & Politics in Bihar’s Villages

[Report] An excellent comparative study on tariffs in electronics by ICEA.

#155 The Persistence Of Memory (of bad ideas)