ONE DAY, TRAVIS BARKER would like to get on an airplane again. He won’t know when it’s coming, but he has an agreement in place with someone very close to him: They’ll tell him to be ready to go in 24 hours, and Barker will know exactly what for. He’ll pack an overnight bag and get in a car that will take him to an airport, where he’ll board a plane for the first time since 2008, when doing so changed the course of his life.

“There’s a million things that could happen to me,” he says one unseasonably warm afternoon in late March, sitting shirtless in a lounge chair in the backyard of his longtime home in the Calabasas hills outside Los Angeles. “I could die riding my skateboard. I could get in a car accident. I could get shot. Anything could happen. I could have a brain aneurysm and die. So why should I still be afraid of airplanes?”

Barker has every reason any person could have to never set foot on an airplane again. The drummer and producer, famous for his formative career with Blink-182 and for his high-profile relationships (currently with Kourtney Kardashian), is in a subset of the population so small it barely exists as a category: He is the last remaining survivor of a plane crash.

In September 2008, after playing a South Carolina show with his friend and collaborator Adam “DJ AM” Goldstein, Barker boarded a private plane with AM and two close friends, assistant Chris Baker and security guard Charles “Che” Still. During takeoff, the tires blew, and the plane overran the runway, skidded across a highway, hit an embankment, and burst into flames. The two pilots, along with Baker and Still, were killed; Barker and AM were able to escape through an emergency exit. Barker was covered in jet fuel and engulfed in flames. He sprinted across the highway on fire; AM eventually helped put it out with the shirt off his own back. Barker, who’d already had a lifelong fear of flying, suffered third--degree burns on 65 percent of his body and spent three months in the hospital, where he underwent 26 surgeries and multiple skin grafts. He was unable to attend his friends’ funerals. Almost a year after the accident, AM died from a drug overdose.

When you’re lucky enough to survive an ordeal that should have killed you, no one will fault you for excising that particular risk from your life, for allowing yourself the luxury of hopefully not going up in flames ever again. But Barker says he will fly again. “I have to,” he says, nodding. “I want to make the choice to try and overcome it.”

Barker has done the work to move on from the night his life changed, to reclaim his traumatized body and mind. He learned to walk and drum again and did months of therapy; more recently, he’s gotten into boxing and breath work. In February, he became one of the most unlikely faces of the Goop-paved celebrity wellness trend when he introduced his vegan CBD line, Barker Wellness Co. He’s continually working on new music, and there’s a documentary on his life in the works.

With all that recovery behind him, flying again is not only about closure. Barker also likes to imagine how redemptively normal it would feel to return home after the trip—to walk through his front door and drop a bag onto the floor and hear his kids’ voices from the other room. “If I do it, and the angels above help me in my travels and keep me safe, I would like to come back and [tell them], ‘Hey, I just flew here, and then I flew home. And everything was fine.’ I have to tell them, because I almost left them,” Barker says. He sits back and looks out across his yard, relishing a fantasy that would sound routine to most everyone else but is still out of reach: “That’s a perfect day.”

BEFORE HE BECAME KNOWN, as he puts it, as “that dude who survived a plane crash,” Barker was largely known as the prodigiously talented drummer for the pop-punk band Blink-182. He was born and raised in southern California’s Inland Empire, where he started taking jazz lessons and playing in a drum line at age ten. After high school, he played around in L. A.-area ska and punk bands and built up a reputation as an innovative and captivating drummer. In 1998, Mark Hoppus and Tom DeLonge recruited him to join Blink-182; a year later, the trio ran naked through Los Angeles for the “What’s My Age Again?” music video, and their album Enema of the State went platinum.

Beyond Blink, which enjoyed huge commercial success through the early aughts, Barker’s creative life took off. He founded a clothing line, joined the punk-rap supergroup the Transplants, and married and started a family with the model Shanna Moakler, with whom he costarred on a short-lived but beloved MTV reality show, Meet the Barkers. (It aired for less than two years—as long as the marriage lasted. The two now share custody of their children, Landon, 17, and Alabama, 15; Barker is also stepfather to Atiana De La Hoya, Moakler’s daughter from a previous relationship.)

After Blink-182 went on hiatus in 2005, Barker began working more in hip-hop, and in 2008 he teamed up with AM to form TRV$DJAM. AM mixed tracks onstage, and Barker drummed live to them. They started to book regular gigs and played the MTV Video Music Awards that summer; Barker writes in his 2015 memoir, Can I Say, that he felt like he was “building a new foundation to my musical career.” But their tragic flight out of Columbia, South Carolina, came just 12 days after the VMAs. They played a few more times together, including a triumphant set at Coachella the next spring, before AM’s death in 2009.

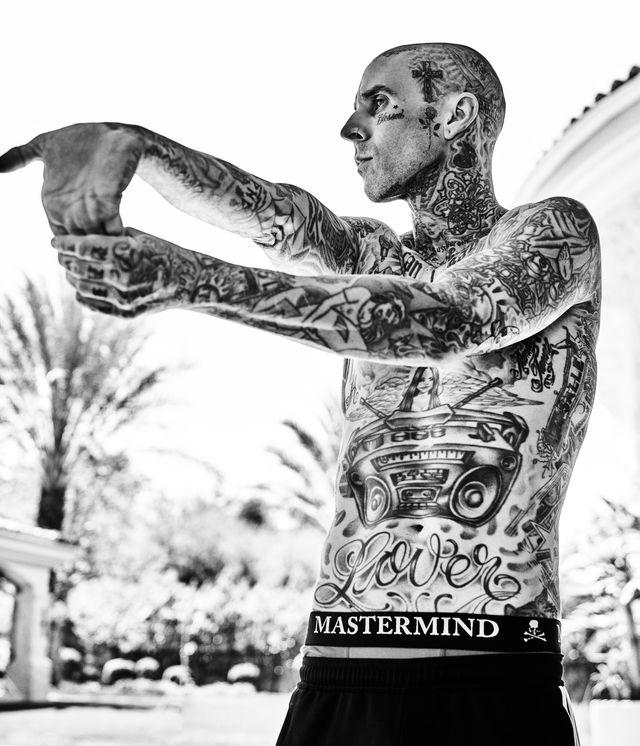

Barker is soft-spoken and gentle in conversation, a demeanor at odds with his ferocious approach to the drum set. He is a committed father and brightens when he tells me how he recently caught his kids on his security camera taking his car for a joyride. He has vivid, light-blue eyes and a preternatural comfort with making prolonged eye contact. He is covered in tattoos—he describes them as a “scrapbook of my life”—including a fresh cursive Kourtney above his left nipple. (A glimpse of the tattoo is the most I’ll get on that topic, though. Barker has been in the public eye for 20-plus years, but he’s guarded about his love life. When I ask about Kardashian, he politely tells me he won’t be addressing their relationship: “I mean, it’s everywhere,” he says.)

It makes sense that Barker might feel protective over this new part of his life. He has been asked to tell the story of the day he nearly died many times, and his publicist had warned me he might not want to get into the grisly details. I can understand a version of this fatigue: I survived a near--fatal car accident in 2015. Like Barker, I spent months in hospitals and rehabilitation, undergoing surgeries and eventually learning to walk again; unlike Barker, I have a fellow survivor with whom I can share my darkest thoughts and my gripes about lingering pains, or even just a knowing, appreciative look across a room. When Barker lost AM, he lost the only other living witness to the most precarious moments of his life.

When AM was alive, Barker says, “we were each other’s therapists.” Together, they tried to find support networks for people who had survived plane crashes but found they only really existed for people who had lost loved ones. “So it was just him and me. When he left, I was like, ‘Oh, fuck. I’m the only one in my club. It’s just me.’ And I find my ways to deal with it.”

The experience of cheating death is a natural dividing line in one’s life: the before and the after. For Barker, it motivated his decision to live healthier and quit abusing prescription drugs. He says he was never a big drinker but prior to the crash smoked “an excessive amount of weed”—up to 20 Backwoods blunts a day—and his painkiller habit, which began as a way to cope with his fear of flying during Blink tours, was bad enough that he depleted his body of calcium and developed osteoporosis. In the hospital, he frequently came to during surgeries because his opioid tolerance was so high. By the time he got out, he’d had enough. He flushed all the medications he’d been sent home with down the toilet—“including stuff that I really needed”—and never looked back.

“People are always like, ‘Did you go to rehab?’ ” Barker says. “And I [say], ‘No, I was in a plane crash.’ That was my rehab. Lose three of your friends and almost die? That was my wake-up call. If I wasn’t in a crash, I would have probably never quit.”

He will have the occasional drink, and he’s slowly testing THC edibles for Barker Wellness Co., a gritty and different player in the burgeoning field of celebrity-branded cannabinoid wellness products. “I felt like there was a gap in the marketplace,” Barker says. “I never really care about, like, ‘Oh, do I fit the mold to do this or that?’ I almost like being like, ‘Fuck it, even better if I don’t.’ ” He says he started using CBD “religiously” to recover from exhausting tours, when he was drumming five hours a night. He got the idea that he could improve upon the products he was using, making them both cruelty-free and vegan. These days, he uses his company’s CBD ointments and tinctures to manage residual pain and to help him sleep, and he says he will never do hard drugs again.

Barker’s physical recovery from the crash was grueling. As a punk-rock drummer, he is accustomed to pushing his body and living hard—he’s been supergluing his torn-up hands shut after shows for 20 years, and he is a multimillionaire with a broken phone screen. “I definitely do push my body,” Barker says. “I know that it’s resilient.” While he was bedridden in the hospital, his muscles atrophied; he had to learn to walk again and feared he would lose his sense of rhythm.

“I was told I wasn’t going to run again because I had so many grafts on my feet, and there was even talk of me never playing the drums again,” Barker says. He treated it all as a challenge. (Barker, a lefty, taught himself to drum right-handed.) “As soon as I could walk, I could run. As soon as I could move my hands and my hands healed, I was playing drums. And now I’m in better shape than I’ve ever been.”

Barker has been vegan since 2009, regularly runs three to four miles a day, and works out with a boxing trainer. A few days after we talk, he posts a video of himself snowboarding cautiously but joyfully in Deer Valley, Utah, on a trip with Kardashian and his kids. He also drums every day, which for him serves as both a full-body workout and a necessary mental reset—he feels off if he doesn’t play.

After the crash, Barker struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder. He barely slept the first three weeks he was home from the hospital—he was lucky to get an hour or so after finally going into his kids’ rooms in the wee hours of the morning. He did three months of therapy to deal with PTSD and intense survivor’s guilt. “I was dark,” he says. “I couldn’t walk down the street. If I saw a plane [in the sky], I was determined it was going to crash, and I just didn’t want to see it.” For a long time, and especially on tour-bus trips, he felt like he was always bracing for impact, waiting for the next catastrophic thing to happen.

With time and therapy, those feelings have finally started to recede. “It’s gotten better the further I get away from it,” Barker says. He holds his hands apart in front of him, two ends of a mental timeline, and explains: “The closer I was to it, it felt like I was closer to the bad stuff than I am to the good stuff. I felt closer to the experience of trying to escape, [to] being in an accident and being burned, trying to grab my friends from a burning plane. That haunted me for a long time. And as long as I was closer to that than this good stuff, I was always thinking about that. Now it’s been so many years, it’s getting easier for me. There are days where I’ll wake up and never think about it.”

To cope, Barker has developed his own methods. He is justifiably superstitious; when any dark hypothetical comes up in our conversation, he knocks a few times on the wooden arm of his chair. His tattoos are part of his narrative and document events and people. “I have memorials on my legs for everyone that I lost in my plane crash, friends that have passed over the years, and my mom.” (His mother, Gloria, died after a battle with cancer when Barker was 13.) Though he now travels by car and bus and has taken the Queen Mary 2 to Europe almost a dozen times, he still employs a calming visualization practice before trips: He closes his eyes and pictures a white horizontal line in the distance. Before he plays a show, he takes a moment to think purposefully about everyone he’s lost.

Barker, a known workaholic, hasn’t played in front of a live audience since before the pandemic and says he’s never spent so much time at home. Without touring, he threw himself into launching Barker Wellness Co. and his production work with artists like Machine Gun Kelly, KennyHoopla, and Yungblud, as well as new Blink songs. He’s savored the extra time with his kids and in his new relationship: Their trip to Utah was the first real vacation he’d ever taken. “I’ve tried to call things vacations, and my kids are like, ‘Dad, this isn’t a vacation. We’re on tour,’ ” he says, laughing.

He still treats his post-traumatic work as an ongoing project, and late last year Barker’s massage therapist suggested he try out breath work. “You may be holding on to some trauma that otherwise you might not be able to get out of your system,” she told him. He watched a few videos and saw people crying and convulsing. “Giving up, letting go to where my body may react like that—it was scary to me.”

Barker tried it eventually, just after the new year, and had an almost psychedelic experience. “It was life changing,” he says. “It began with a series of breaths.” He demonstrates a few short, harsh exhalations, snapping along at a set tempo. “And it’s an uncomfortable way to breathe. But you actually get into the rhythm of it, where you’re not even thinking about it. Your body’s shaking; it’s almost like how some people shake before an orgasm.”

When he finally yielded to what he was feeling, he lost control and tears streamed down his face. He felt an intimate and overwhelming connection with his mother and with other people he’d lost. In breath work, he says, “it’s really up to you; there’s no one else guiding you. Your soul is guiding you, and it guided me to my mom. It was like I was in a different world.” Once it was over, he felt relief, “like a huge weight had been lifted off my chest.” He did another session with his son and would like to do more. “You have to constantly practice it, letting go of the trauma,” Barker says. “You know what I mean? Just to be like everyone else.”

He feels like he’s getting there—closer to the good stuff than the bad stuff, as he puts it, closer to the day he might decide to get on a plane again, then come back home to his kids and tell them about it. With them, Barker says, “I have all the love I need in my house. It will never make sense why my friends are gone, or the pilots, but all I can do is carry on. I can’t regret anything. I’m 100 percent supposed to be here.”

Still, I say, it’s easy sometimes to wish it had never happened.

“Yeah,” he says, nodding. “But I can’t imagine it any other way, either.”

This story appears in the June 2021 issue of Men's Health with the title Keeping Up With Travis Barker.