SAN FRANCISCO—While the game series Doom and Quake have been heavily chronicled in convention panels and books, the same can't be said for id Software's legendary precursor Wolfenstein 3D. One of its key figures, coder and level designer John Romero, appeared at this year's Game Developers Conference to chronicle how this six-month, six-person project built the crucial bridge between the company's Commander Keen-dominated past and FPS-revolution future.

And if six months for a landmark game seems fast, you should pause for a history lesson.

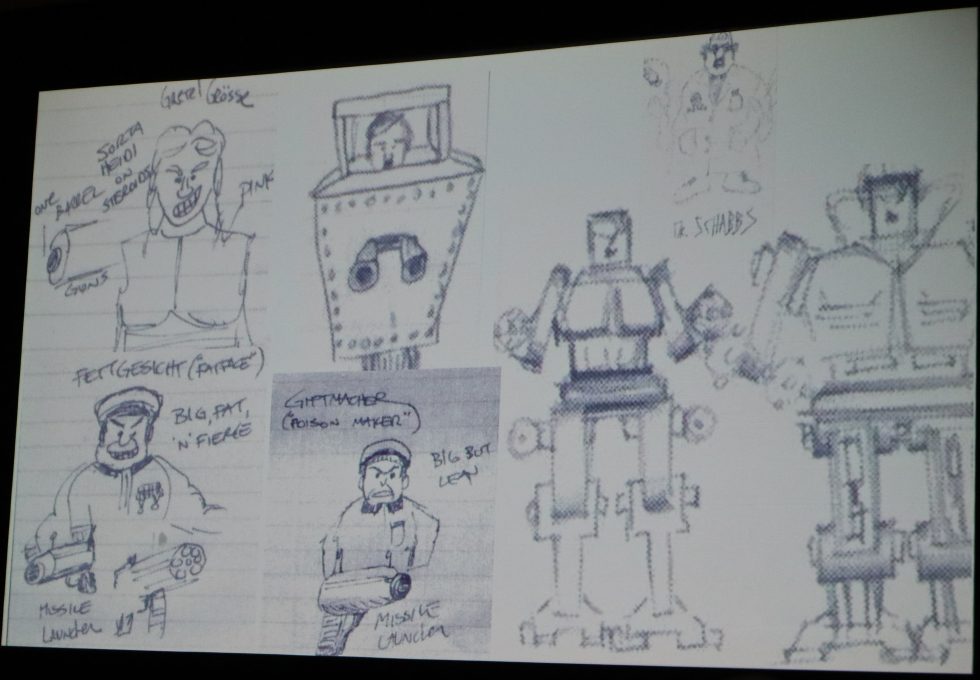

"In the last six months of 1991, we started and shipped five games," Romero says as a lead-in to the genesis of Wolfenstein 3D's development. This included multiple Commander Keen side-scrolling games, and id Software began the year of 1992 by prototyping the game that would have been Keen 7, whose major technological advancement would have been parallax-scrolling backgrounds. After helping id Software complete the game's first demo in one week, Romero announced that he wasn't interested in keeping the Keen series going. id Software co-founder Adrian Carmack agreed—"I'm sick of Keen"—and John Carmack (no relation) "viewed the carnage" and assessed that a change might very well be in order.

"We should make another 3D game with texture mapping," Romero suggested, as a nod to the slow-but-novel game Catacomb that they'd also shipped in 1991. After co-founder Tom Hall suggested an on-foot follow-up to id's 1991 curio Hovertank (seriously, what a busy year!), Romero says he countered "instantly" with his own pitch: a 3D remake of the 1981 Apple IIe classic Castle Wolfenstein. "That idea won instant approval," he says.

-

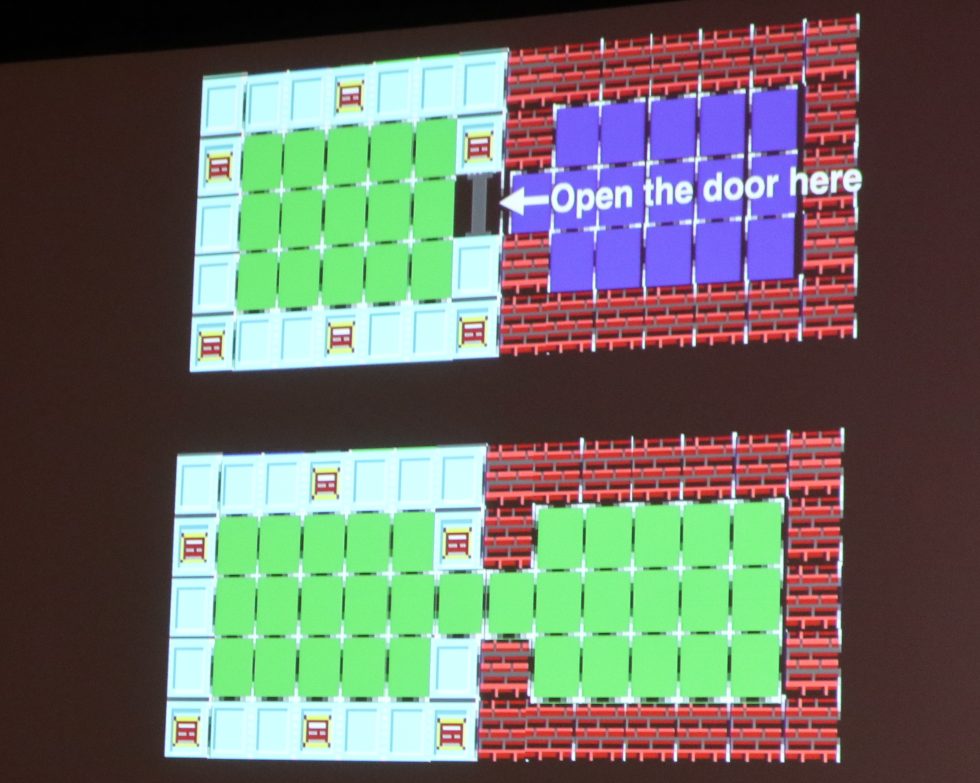

id Software used original level-design software to build maps in Wolfenstein 3D.Sam Machkovech

-

id Software used original level-design software to build maps in Wolfenstein 3D.Sam Machkovech

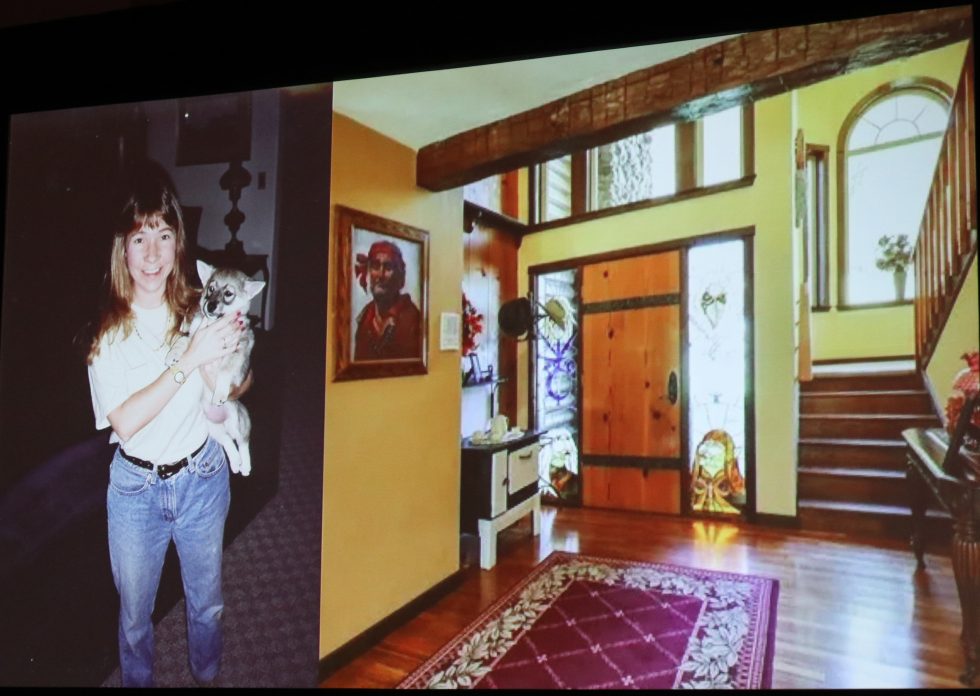

There was a catch, however: Work on the id Software remake began before anyone involved, including publisher Apogee, had secured the rights to the classic Muse Software series. Could that happen, or would id Software have to rename the game? (Romero was stubborn: "We tried coming up with a new name, but nothing was cool enough.") In April 1992, assistant artist Kevin Cloud was tasked to track down Castle Wolfenstein's rights. Weeks later, he discovered that a woman owned the entirety of Muse's output, and she was willing to sell the Wolfenstein trademark outright to id Software for $5,000.

During the panel's Q&A, Romero confirms that id Software not only met Castle Wolfenstein creator Silas Warner but showed him Wolfenstein 3D's retail version shortly after its 1992 launch. To do this, folks from id drove to Kansas City with a $5,000 color Toshiba laptop in tow to meet Warner at a convention where he was speaking. At the event, Warner signed one of id Software's Wolfenstein 3D printed manuals, which Romero says is still at id Software's offices.

Gatling over stealth; independence over Sierra

By March 1992, id Software had gutted some of the gameplay elements that made the original Apple IIe game an office favorite. The company's original development plan included the sneakier aspects of the 1981 game and its 1984 sequel: walking carefully, searching dead bodies for loot, dragging incapacitated guards out of hallways to avoid being spotted, and picking locks for items. While playtesting the early first-person action, as tuned by engine lead John Carmack, the team discovered something surprising.

"The more fun part was running and gunning," Romero says. "Stopping to drag a guard or unlock a chest really slowed down the innovative, high-speed running and blasting Nazis at the core of the game." The new game's thrilling nature was aided in particular by a directive from publisher Apogee, who insisted the game support SoundBlaster sound cards and their robust digital sample playback. "The sound of the Gatling gun, the enemy shouting sounds, the pain sounds, and the death sounds: They were the heartbeat of the game," Romero says.

id Software decided to "listen to the game" once its most exciting aspects became apparent, and Romero uses this as a teaching moment: "When you're making a game, you're trying to find the fun as soon as you can. And sometimes, the fun isn't in the features that you thought were going to be fun." And so Wolfenstein 3D's stealth elements were wholly jettisoned within its first month of development.

At the start of February, Roberta Williams, legendary designer of the King's Quest series, invited the id Software staff to visit her home in Oakhurst, California, after receiving a copy of Commander Keen from Romero in the mail and enjoying it. The visit included a full tour of gamemaker Sierra's offices, as co-hosted by programmer and Sierra co-founder Ken Williams, and a chance encounter with legendary game coder Warren Schwader, who Romero says was responsible for all of his father's favorite PC games.

This was followed by the folks from id Software eagerly showing both Williamses their latest build of Wolfenstein 3D. "[Ken] was not visually impressed," Romero says. The demo was cut short after only 30 seconds, at which point Ken booted up a copy of Red Baron. "I was dumbfounded," Romero says. "Here's the future, the start of a new genre, the first-person shooter, and Ken did not pay any notice." (It reminded him of the same cold response his team got from showing off Dangerous Dave, the precursor to Commander Keen, to the publishing team at Softdisk 18 months earlier.)

Still, between the Wolfenstein 3D demo, the existing Keen output, and id's ability to make $50,000 a month selling shareware, Ken was charmed enough to make id Software an offer: a total company buyout for $2.5 million of Sierra stock. Romero and his colleagues mulled the offer for a day, then countered that they'd take the deal if it included an immediate payment of $100,000 and a letter of intent. "No thanks, but good luck with everything," Ken replied.

In a GDC 2022 interview with Ars Technica, Ken Williams confirms Romero's account is accurate, and he now admits some remorse: "I should've done the deal," he says.

“The sanctity of his code”

As far as getting the game out, Romero doesn't offer horror stories about major stopgaps in the art, coding, music, sound, or level-design process. The biggest exception is a story about a major gameplay change that happened two months into development and how it required buy-in from John Carmack.

The issue stemmed from the lack of secret areas in the earliest levels. How could Wolfenstein 3D reward players who poked around and searched for hidden trinkets? Romero and Tom Hall suggested "push walls," which would use non-door textures to hide a mix of door animations and unique sounds that players would find if they tried to "open" the right non-door part of the wall.

"John didn't want to add push walls," Romero says. "It'd violate the sanctity of his code. It'd be a hack."

But the level designers were in a bind, having no other clever system available in Carmack's otherwise blistering 3D-textured engine to hide secrets. By the end of the following month, Carmack "heard the request enough times" and caved. This led to an explosion in secret areas, and Hall interrupts Romero from the GDC audience at one point in the talk to own one of his follies: "Sorry about the maze that you can't complete!" Moments later, he unbuttons his shirt amid the GDC crowd to reveal an original Wolfenstein 3D T-shirt.

reader comments

134