NASA’s next-generation space observatory has sustained its first noticeable micrometeoroid impact less than six months after launch, but the agency isn’t too concerned.

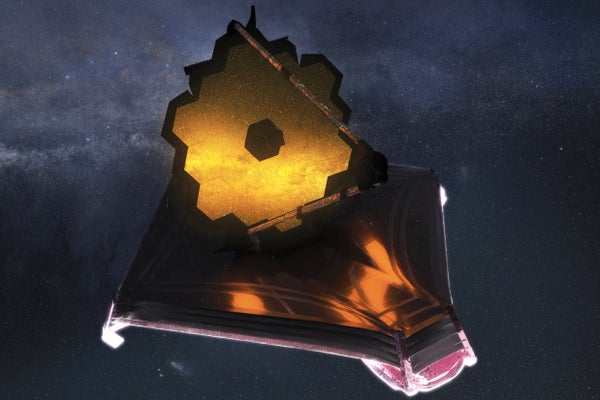

The James Webb Space Telescope, also known as Webb or JWST, launched on Dec. 25, 2021. It has spent the intervening months trekking out to its deep-space post and preparing for science observations, a complicated process that has gone remarkably smoothly; recently, NASA said it expects to unveil the first science-quality images from the telescope on July 12.

Now, the agency announced on Wednesday (June 8) that the observatory has experienced its first few impacts from tiny pieces of space debris called micrometeoroids. But don’t panic: Neither the observatory’s schedule nor its scientific legacy is expected to suffer.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“With Webb’s mirrors exposed to space, we expected that occasional micrometeoroid impacts would gracefully degrade telescope performance over time,” Lee Feinberg, Webb optical telescope element manager at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, said in the statement. “Since launch, we have had four smaller measurable micrometeoroid strikes that were consistent with expectations, and this one more recently that is larger than our degradation predictions assumed.”

The most serious of the impacts occurred between May 23 and May 25 and affected the C3 segment of the 18-piece gold-plated hexagonal primary mirror, according to the statement.

All spacecraft are expected to experience and designed to withstand micrometeoroid impacts, and JWST is no different. The observatory’s engineers even subjected mirror samples to real impacts to understand how such events might affect the mission’s science.

However, the recent impact was larger than those that mission personnel had modeled or could test on the ground, according to the statement.

Despite the impact coming so early in the observatory’s tenure, NASA officials are confident that the $10 billion telescope will still perform adequately.

“We always knew that Webb would have to weather the space environment, which includes harsh ultraviolet light and charged particles from the sun, cosmic rays from exotic sources in the galaxy, and occasional strikes by micrometeoroids within our solar system,” Paul Geithner, technical deputy project manager at NASA Goddard, said in the statement. “We designed and built Webb with performance margin — optical, thermal, electrical, mechanical — to ensure it can perform its ambitious science mission even after many years in space.”

In addition, JWST launched with its optics in even better shape than the agency bargained for, officials noted in the statement.

Some micrometeoroid impacts can be predicted, officials wrote. For example, when the spacecraft is set to fly through known meteor showers, personnel can maneuver JWST's optical systems into safety for these events. However, the recent impact was not part of such a meteor shower and the statement classified it as "an unavoidable chance event."

After an impact occurs, engineers can individually adjust the 18 primary mirror segments on the observatory to keep the mirror as a whole finely tuned.

As the JWST team continues to evaluate the impact, NASA is focused on better understanding both the particular event and the environment that the observatory will experience throughout its mission. The telescope is orbiting what scientists call the Earth-sun Lagrange point 2, located nearly 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from Earth in the direction opposite the sun.

“We will use this flight data to update our analysis of performance over time and also develop operational approaches to assure we maximize the imaging performance of Webb to the best extent possible for many years to come,” Feinberg said.

Copyright 2022 Space.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.