Editor’s Note: Peniel E. Joseph is the Barbara Jordan chair in ethics and political values and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is also a professor of history. He is the author of several books, most recently, “The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.” The views expressed here are his own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

This year’s holiday honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., happening in the wake of of a White mob’s sacking of the US Capitol and an unprecedented second impeachment of President Donald J. Trump, offers the United States a chance to recover and connect with the most powerful and resonant aspects of America’s apostle of nonviolence.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s political life roughly corresponds with the arc of the civil rights movement’s heroic period, between the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision mandating desegregation and the 1968 Fair Housing Act, the latter legislation passed just days after King’s assassination in April of that year. This era represents America’s Second Reconstruction, a post-World War II social movement for racial and economic justice.

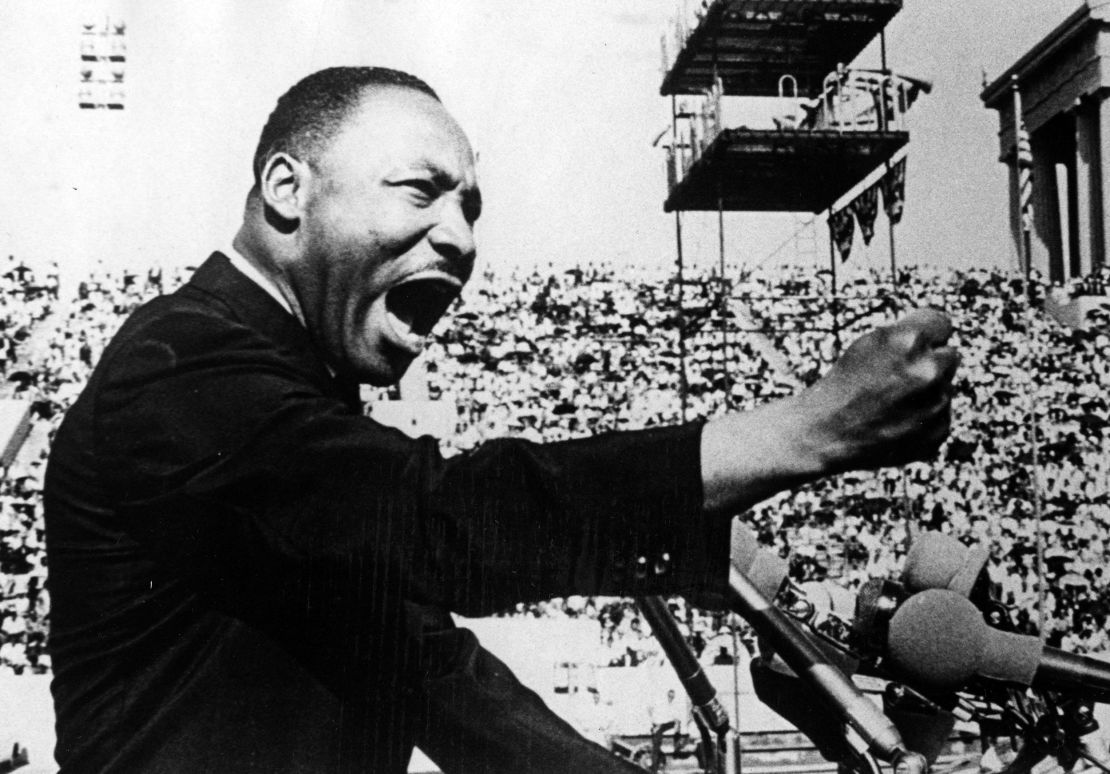

As that movement’s leading political mobilizer and most celebrated figure, King routinely faced off against racist opponents in government, business, church hierarchy and all aspects of American society – many of whom would probably have stood proudly alongside those who stormed the Capitol. The roots of the White supremacist tree that has flourished in the age of Trump are deep, and King combated these forces in his own time with a moral clarity that turned him into a radical political agitator who broke with his former political ally, President Lyndon B. Johnson, on the issue of Vietnam, and a revolutionary human rights leader who vowed to help end militarism, racism and materialism before it destroyed American society.

Many Americans have rightfully expressed shock, horror and anger at images of White rioters at the US Capitol last week creating mayhem that left five dead, including a Capitol Police officer, and the subsequent photos of National Guard troops sleeping on the marble floors of the Capitol rotunda to protect it from further insurrection as members of the House of Representatives debated and then impeached the US President for the second time.

Yet it is important, as we approach the King holiday, to face up to the uglier aspects of our recent history, which we continue to ignore at our own national, political and moral peril.

King’s political courage in speaking out against racism, poverty, violence and American imperialism in foreign policy shows us a way forward. America needs the revolutionary King now more than ever. While always maintaining his commitment to non-violence, this King stalked the nation like a pillar of fire, an Old Testament prophet both recognized and shunned – as he does even today, in a nation that has embraced him more in death than in life.

During his last revelatory year of political activism and organizing, King demanded a maturity of Americans that we have yet to embrace. A mature nation, suggested King, possessed the grace to look inward, identify and assess its mistakes, and move forward through an examination of a past filled with troubling injustices and glorious instances of progress rooted in social movements that expanded the boundaries of democracy.

This year calls us, once again, to seek renewal in what King characterized as “those great wells of democracy,” not by ignoring our past mistakes but embracing our messily complex history and all of its flaws. By doing so, we will never again be shocked, stunned or surprised at assaults on democracy that are deeply rooted in a failure to recognize how America’s past continues to shape its present and to imagine that things can truly be different.

King preached his last Sunday sermon in Washington, DC against a growing backdrop of racial and civil unrest that bears a striking resemblance to our own. In King’s era, Richard Nixon, George Wallace and Barry Goldwater all vied to achieve political power by galvanizing White voters fearful that gains for Black Americans meant a loss of prestige, privilege and power for Whites.

In his rise to power, President Trump turned racially based appeals directed at a long-simmering base of angry White voters into a political art, one that fueled a racially divisive movement that has threatened the very citadel of American democracy.

There is a striking parallel between 1968 and 2021. In both instances the nation has found itself at a political crossroads defined by ongoing debate and struggle between building a beloved community or retaining a status quo grounded in racial injustice, economic inequality and the marginalization of groups lacking in privilege and power.

In 1968, America chose Nixon’s “law and order” over Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of multiracial democracy – choosing to build systems of punishment that disproportionately undermined Black lives rather than investing in reforms that would promote justice and equity.

The attempted coup at the Capitol, in profoundly disturbing ways, represents the bitter fruits of a harvest of racial division whose immediate historic antecedents were visible after King’s death.

Yet in modern America King’s contemporary legacy abounds. On January 5, 2021 Reverend Raphael Warnock, who presides over King’s former pulpit at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, became the first Black person elected to the US Senate from Georgia. Dr. King’s call at the March on Washington for Georgia and the rest of the nation to look beyond the embarrassment of Stone Mountain’s dedication to White supremacy and the Confederacy resonated clearly through Georgia in last year’s presidential election and two Senate run-offs earlier this month.

The revolutionary King bluntly confronted the challenges to his dream of transforming the nation into a beloved community. “It is an unhappy truth that racism is a way of life for the vast majority of white Americans, spoken and unspoken, acknowledged and denied, subtle and sometimes not so subtle – the disease of racism permeates and poisons the body politic,” he observed during his brilliantly provocative Passion Sunday sermon at Washington’s National Cathedral on March 31, 1968.

This is the King many would rather conveniently forget, especially those conservatives who insist on using his words in defense of White supremacy.

The White riot at the Capitol reminds us that King’s warnings about racism’s dangers to American democracy continue in our own time. This most recent assault on democracy has rightfully been compared to the rise of White supremacy during America’s First Reconstruction, the fitful period following racial slavery and the Civil War, where efforts to guarantee Black citizenship, dignity, and voting rights existed uneasily alongside racial terror, voter suppression and Jim Crow laws that innovated racial segregation as a matter of local and state preferences, ungoverned by the Constitution.

Yet last week’s insurrection, which included the striking image of a rioter holding a Confederate flag in the Capitol, echoes large aspects of the violent opposition that King faced in his own era. The rise of White Citizens Councils comprised of leading Southern civic, clergy and business leaders, in the wake of court-ordered school desegregation sparked what came to be known as “Massive Resistance” against Black citizenship and dignity.

Massive resistance became a euphemism for White supremacy, and the White Citizens Council put an officious image on racist sentiments that found common ground with the Ku Klux Klan and other more clandestine racial terror groups.

This generation of Americans has an opportunity to choose a different path. It is one that may very well be more difficult than we would like to imagine, since it is a road the nation has yet to embark on.

The greatest testament to Dr. King’s legacy this year will be in the collective effort to reimagine an America that is mature enough to explain the events of the last year and this one, not as a mere pit stop on the road to democratic perfection or an aberration on an otherwise healthy body politic. King would surely shy away from using his holiday as an example of American exceptionalism – and would instead push us toward the hard work of building, for the first time in our nation’s history, a racially inclusive democracy that will ensure that this latest attack on the sacred citadel of American democracy will be the last.