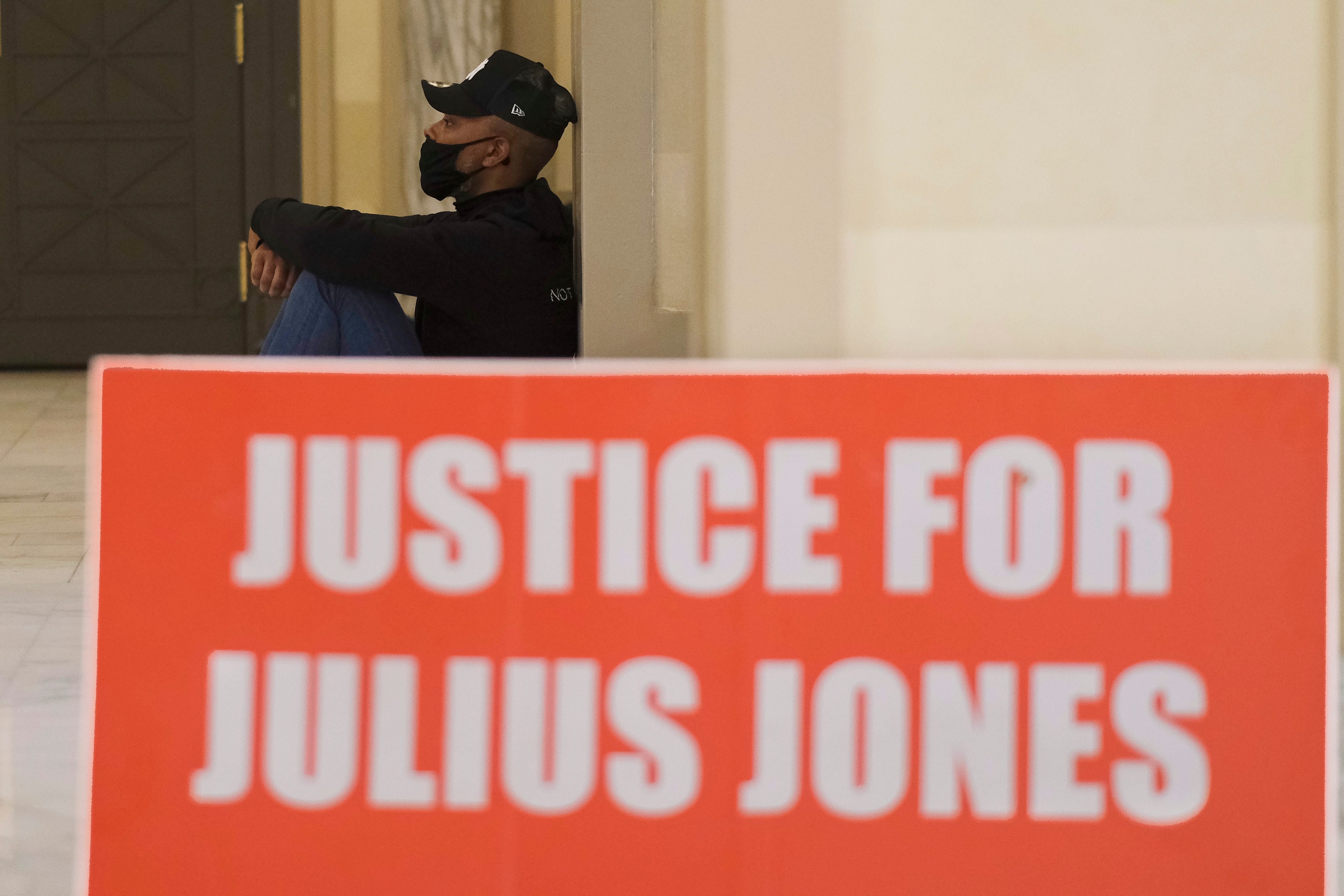

Oklahoma’s Republican governor, Kevin Stitt, commuted the death sentence of Julius Jones just hours before his scheduled execution on Thursday. Given the overwhelming support for capital punishment in the state and the fact that Oklahoma had only recently resumed executions after a six- year hiatus, Stitt’s decision seemed a bit out of character and even a hopeful sign for abolitionists.

But, on closer examination, Stitt’s commutation turns out to be both a reminder of the rarity of clemency in capital cases and an example of cruelty masquerading as mercy.

Jones has spent 20 years on death row, having been convicted and sentenced for the 1999 murder of businessman Paul Howell. Howell was gunned down while sitting in his car in the driveway of his parents’ home. From the moment he was arrested, Jones has maintained his innocence.

He had a strong alibi but suffered from an inadequate legal defense. He and his family say he was at home the night Howell was killed and that he was framed by a co-defendant, Chris Jordan, who was given a plea deal and reduced sentence in return for testifying against Jones. Jordan reportedly told others later that his testimony against Jones was false and that he, not Jones, murdered Howell.

Jones’ case attracted international attention, with celebrities like Kim Kardashian and Steph Curry weighing in on Jones’ behalf. They were joined, among others, by five Republican members of the Oklahoma Legislature and Matt Schlapp, head of the American Conservative Union.

And, in an extraordinary turn of events, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board twice recommended that the governor exercise his clemency power in Jones’ case. Given the doubts raised about Jones’ guilt, they recommended commuting his sentence to life in prison with the possibility of parole. Such a commutation would have made him immediately eligible for parole.

Jones is only the sixth person ever to have been granted clemency since Oklahoma joined the union in 1907.

Gov. Stitt accepted one part of the board’s recommendation and rejected the other. As he explained in a brief statement accompanying his commutation: “After prayerful consideration and reviewing materials presented by all sides of this case, I have determined to commute Julius Jones’ sentence to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.”

Americans should celebrate the fact that Jones will not be executed, but after that celebration we need to ask what kind of mercy would ignore the Pardon and Parole Board’s recommendation of life with the possibility of parole? What kind of mercy would insist that Jones spend the rest of his life and die in prison for a crime that the evidence suggests he did not commit?

The answer: It is not mercy at all. It is its own kind of cruelty.

The governor’s commutation seeks to satisfy two different political imperatives. First, it recognizes and responds to an injustice so great that even the American Conservative Union was moved to speak out. But, second, by substituting the recommended sentence of life in prison with the possibility of parole for life in prison without parole, Stitt showed his tough-on-crime base that he was not going easy on a convicted murderer. His tough-on-crime approach is very much in keeping with the recent history of clemency in capital cases.

Clemency rates have in fact plummeted. From 1973 to the end of 2020 there were 8,752 death sentences handed down in the United States. During that same period there were 294 commutations and pardons granted to people on death row. That adds up to a clemency rate of .02 percent.

This minuscule percentage represents a radical shift from the period from 1900–73, when governors granted clemency in 20–25 percent of the death sentences they reviewed.

In the most recent period, when governors have granted clemency in capital cases, they have done so almost exclusively to undo, as was the case with Jones, some miscarriage of justice.

Even in those cases, governors like Stitt have issued statements assuring their constituents that being moved off death row to a life sentence is no picnic.

Take, for example, former Illinois Gov. George Ryan. In 2003, he emptied his state’s death row, granting four pardons and commuting 167 death sentences to life without parole. At the time, Ryan said, “Some on death row don’t want a sentence of life without parole…. It is a stark and dreary existence…Life without parole has even, at times, been described…as a fate worse than death.”

Clemency without mercy or compassion has become the order of the day in capital cases. But Stitt went further than withholding mercy or failing to show compassion. As if requiring Jones to suffer a “fate worse than death” were not enough to demonstrate his toughness, Gov. Stitt added the following:

“I hereby place the following conditions upon this commutation: Julius Darius Jones shall not be eligible to apply for or be considered for a commutation, pardon, or parole for the remainder of his life.” (bold and italics in the original)

Imposing conditions on clemency grants is not unusual and has been recognized as legitimate by the United States Supreme Court in a line of cases going back to its 1855 decision in Ex Parte Wells.

But the condition Stitt imposed flies in the face of the very reason he decided to spare Jones’ life, namely to remedy the very real miscarriage of justice that occurred in his case.

Saying that Jones now must relinquish the right to seek any future “commutation, pardon or parole” is unprecedented and arguably incompatible with the broad and unlimited power that Stitt himself asserted when he said that “The Governor has the power to grant commutations ‘upon such conditions and with such restrictions and limitations as the Governor may deem proper’…’”

Whether he can get away with such a blatant attempt to limit the power of future governors to exercise their own clemency power in Jones’ case is for the courts to decide.

In the meantime, the bold and italics in the governor’s order signals for all to see Stitt’s sadistic gesture—snatching hope from Jones in the same moment that his life was spared.

Seeing that gesture embedded in an act of executive clemency called to mind what the journalist Adam Serwer wrote about former President Trump, that the cruelty of his policies was neither accidental nor incidental. The cruelty was, Serwer, wrote, precisely the point. It was designed to make his supporters “feel good,” “feel proud,” “feel happy,” and “feel united.”

Even as his life was rightfully spared, Julius Jones deserved better than to be used in this way.

And America deserves better than to be led by politicians, whether at the state or national level, who turn even their rare acts of clemency into cruelty.