N. Chandrasekaran, Chairman, Tata group

N. Chandrasekaran, Chairman, Tata group  N. Chandrasekaran, Chairman, Tata group

N. Chandrasekaran, Chairman, Tata group Tata Power, set up in 1915, held its 100th annual general meeting on June 18, 2019. While it should have been an occasion to celebrate, with net debt of Rs 47,552 crore in FY19 and a net debt-to-EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxation, depreciation and amortisation) ratio of seven, there was not much to celebrate. When shareholders asked Tata Group Chairman N. Chandrasekaran what he was doing to reduce the company's liabilities, he looked visibly irritated. "We're working on a solution; it's not that we are not trying hard," he said.

In the first nine months of FY2020, Tata Power repaid Rs 2,257 crore debt. But for Chandrasekaran, who completes three years as the head of the Tata group on February 21, that is little relief. The gross debt of 11 major indebted listed companies in the group - excluding financing companies and holding company Tata Sons - stood at Rs 2.46 lakh crore in FY19 compared to Rs 2.22 lakh crore in FY18 and Rs 2.1 lakh crore in FY17.

Debt pressure is mounting on marquee Tata companies such as Tata Steel and Tata Motors. In the first nine months of FY2020, Tata Steel's net debt increased 10.2 per cent to Rs 1,04,628 crore, while that of Tata Motors' automotive business (excluding lending subsidiary Tata Motors Finance) surged 59.8 per cent to Rs 45,376 crore. While the steel business has been dogged by troubles in Europe, the auto business faces headwinds in India and China and slowdown in demand for diesel cars, which account for a vast chunk of its UK and European business.

Debt Reduction Plans

BT sent a questionnaire to the Tata group, which provided details of its debt handling plan. Besides, Tata Sons executives briefed Business Today.

The net debt - gross debt minus cash in hand, including liquid investments - in these companies stood at Rs 1.39 lakh crore in FY19. If Tata Sons had not cleared the Rs 50,000 crore loans and spectrum liabilities of Tata Teleservices in the last fiscal with dividend and buyback windfall from Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), the debt numbers would have been even higher.

All this would not have been a problem if the companies were earning robust profits to service the debt. But that is not the case with Tata Steel, Tata Motors and Tata Power.

The 11 companies (see The Trap) posted an aggregate loss of Rs 14,765 crore in FY19. This was primarily due to the Rs 28,934 crore loss incurred by Tata Motors. It was Tata Motors' net loss of Rs 28,934 crore that ate away the modest profits of other firms. The most-debt laden firms in the group would struggle to clear their debt with such losses. Tata Steel, for instance, is saddled with a gross debt of Rs 1,00,816 crore, Tata Power Rs 48,506 crore and Tata Motors' automotive division Rs 68,360 crore (as of March 2019).

In comparison, Reliance Industries (RIL) has massive debt but its financials are healthier. RIL had a net debt of Rs 153,132 crore as on December 31, 2019, but the company posted a profit Rs 33,006 crore in the first nine months of the fiscal, which ensures its loan repayment capability. Vedanta Ltd notched a net profit of Rs 9,698 crore in FY19, good enough to repay the loan amount of Rs 23,384 crore. JSW Steel posted a standalone profit of Rs 8,259 crore in the last fiscal, as against its net debt of Rs 49,500 crore.

An executive told BT that the group is significantly comfortable with aggregate net debt of Rs 1.65 lakh crore (which includes all significant businesses in the group for which separate data is not available). The aggregate net debt is lower because of surplus cash on books of TCS, Titan and Voltas. "The group generates an EBITDA of Rs 1.16 lakh crore. So, the net debt is less than 1.5 times the EBITDA," he says.

Being bogged down by debt is a sea-change for the Tatas. In 2006, it was cash-surplus. Then came a series of overseas acquisitions. Tata Steel acquired Anglo-Dutch steel giant Corus for $12 billion in early 2007; this was followed by Tata Motors' purchase of Jaguar Land Rover for $2.3 billion in 2008. Yet, in FY10, the entire group debt was just below Rs 1 lakh crore. The acquisitions continued after a lull as Tata Power picked up Welspun Renewable Energy for Rs 9,249 crore in 2016. The other recent acquisitions are Bhushan Steel (Rs 35,200 crore) and the steel business of Usha Martin (Rs 4,094 crore). "Debt overhang is typically not observed when conglomerates grow organically," says Lakshmanan Shivakumar, Professor, Accounting, London Business School. "It is more common when growth is through acquisitions." This is indeed the case with the Tatas.

But in case of the Tata group, with group revenues of over Rs 8 lakh crore and market cap of around Rs 11 lakh crore, some organic investments too have gone wrong. It invested heavily in building the telecom business in collaboration with Japan's NTT DoCoMo. It invested Rs 18,000 crore to build India's first 4,000 megawatt (MW) ultra mega power plant at Mundra. Many of these investments have failed to bear fruit like the overseas acquisitions.

Because of mounting losses, Tata Steel is shutting down units in Europe one by one. Tata Power says it will not be able to run its Mundra plant beyond February. Tata Tele has paid off its Rs 50,000 crore debt and handed over the mobile services business to Bharti Airtel for free. Tata Motors has shut down production of Nano. In recent news, Tata Sons has initiated the process of arranging funds from TCS to pay Tata Teleservices' adjusted gross revenue dues of Rs 13,823 crore.

This leads to the second issue. The group is over-dependent on TCS, which earned a net profit of Rs 31,472 crore in FY19 and is for all practical purposes the biggest cash generating engine. TCS accounted for around 90 per cent of Tata Sons' dividend income in FY18. Such concentration of risk cannot be good news as things are getting tougher for India's largest IT services firm too. Its large clients in banking, financial services and insurance (BFSI) in the US and the UK, which contribute over 30 per cent to its revenue, are cutting costs. The company is facing structural challenges in the US and the UK, Managing Director and CEO Rajesh Gopinathan said after announcing the results for the third quarter of FY20 in which TCS reported flat profit growth at Rs 8,118 crore vis-a-vis Rs 8,105 crore in the same period last year, largely due to headwinds in BFSI and retail.

Can Chandrasekaran Resolve Big Issues?

It is a wrong perception that Chandrasekaran is not addressing key issues, says the executive working with the chairman's office. "Tata Tele was one of the lingering concerns that has been addressed in the last three years. JLR has improved performance. Tata Steel has refocused back to its core market, India, and acquired Bhushan Steel and the steel business of Usha Martin and acquired steel businesses in the country. We are working to resolve the Mundra crisis," he says. At any point, there will be a running list of issues in the Tata group, considering its size and scale. But a major worry for investors is legacy issues in key businesses which are dragging down market value. The executive says innumerable issues have been resolved in the last three years.

"The group has monetised non-core assets, including Tata Business Support Services and Tata Petrodyne. The group tried to disentangle cross-holdings of group companies which helped some companies find capital. For FMCG ambitions, the group demerged the consumer business of Tata Chemicals and merged it with Tata Global Beverages, which has since been renamed Tata Consumer Products. We are consolidating defence businesses across the group. The most recent is Tata Motors, Tata Chemicals, Tata Power and Tata Croma pooling resources to build the electric vehicle ecosystem," says the executive.

"The retail businesses - Croma, Westside and Star Bazaar (a joint venture of Tata and Tesco) - are growing market share. Tata Capital's book has grown from Rs 50,000 crore to Rs 80,000 crore in the last three years. Insurance joint venture Tata-AIA's market share has gone up from 3.7 per cent to 5.6 per cent. Tata-AIG's share has moved up from 3.3 per cent to 4.6 per cent," he adds.

Still, in spite of these efforts, past acquisitions trouble the group. How did things come to such a pass?

Power Drain

Tata Power's major wealth drain is its 4,000 MW ultra mega power plant at Mundra, Gujarat, run by subsidiary Coastal Gujarat Power (CGPL). The project has been jinxed ever since it was commissioned in March 2013. It has made profits only once in the last eight years. The company has informed the power ministry that it would be forced to stop operating this imported coal-based plant - built at a cost of Rs 18,000 crore - after February unless the five consumer states allow pass-through of additional fuel costs to consumers.

Tata Power had won the project in an open auction by quoting the lowest tariff of Rs 2.26 per unit which, it believed, would be viable if it used cheap coal from Indonesia where it had stakes in coal mines. Soon after, in 2010, the Indonesian government banned export of coal below the notified price, upsetting Tata Power's calculations. Though the Appellate Tribunal on Electricity agreed that Indonesia's decision was an unforeseen one and allowed Tata Power to increase tariff, the Gujarat distribution company it was selling power to contested the verdict in the Supreme Court, which ruled in April 2017 that consumers should not have to pay for Tata Power's misjudgment and the company would have to stick to its quoted tariff.

However, the Supreme Court reconsidered its view in October 2018 and asked the Central Electricity Regulatory Authority (CERC) to decide on changes to power purchase agreements (PPAs) for three imported coal-based plants in Gujarat to let them pass on higher fuel costs to consumers. In April 2019, Adani Power, which had also set up a plant at Mundra, expecting to use the Indonesian coal and was in a similar fix, was allowed by CERC to pass through the increased costs to consumers.

Sources say CGPL has not been able to generate working capital for its operations and had cumulative net losses of about Rs 9,000 crore until the last financial year, funded by Tata Power through equity financing of around Rs 5,000 crore. CGPL's consumer states - Haryana, Rajasthan, Punjab and Maharashtra - have expressed willingness to rework the PPAs but not yet got approvals from their cabinets. Only Gujarat has approved the revised PPA. The five states need to approach the CERC once they approve the revised PPAs.

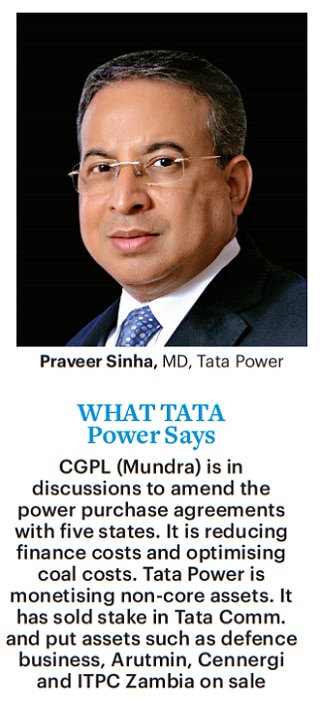

Tata Power has taken steps to reduce finance costs through refinancing loans and optimising coal costs. "With regard to reducing debt, Tata Power is monetising non-core assets. It has already sold its stake in Tata Communications and put assets such as defence business, Arutmin, Cennergi and ITPC Zambia on sale," says the Tata Power spokesperson.

However, Tata Power added to its debt burden with its subsidiary, Tata Power Renewable Energy, buying the solar and wind power assets of Welspun Renewable Energy - around 1,141 MW - in June 2016 at an enterprise value of Rs 9,249 crore. It raised Tata Power's clean energy capacity to 2,169 MW, making it one of the biggest players in the segment, but profits from the venture have so far been modest, falling 52 per cent to Rs 92.53 crore in FY2019. To deleverage, Tata Power is exploring to set up an infrastructure investment trust for its renewable energy portfolio which will reduce debt on its balance sheet by 25 per cent and help it raise equity.

In March 2018, Tata Power sold its stake in Tata Communications and its holding firm Panatone Finvest to Tata Sons for around Rs 2,150 crore to pare debt. Later, it agreed to sell the defence business to group firm Tata Advance Systems at an enterprise value of Rs 2,230 crore. But the deal is yet to conclude.

Consolidated finance costs of Tata Power rose 10.9 per cent to Rs 4,170 crore in FY2019, but the company posted a 6 per cent decline in profit to Rs 2,440 crore on operational revenue of Rs 29,559 crore. Tata Power posted a 12 per cent rise in consolidated profit after tax (PAT) to Rs 246 crore for the third quarter of FY20, thanks to the deferred tax benefit of Rs 272 crore on power purchase agreement (PPA) extension in the Mumbai licensed area. Consolidated revenue went down by 9 per cent to Rs 7,171 crore. The losses at the Mundra power plant decreased, the company said.

Cracked Steel

In 2007, Tata Steel acquired Corus plc for $12 billion, outbidding Brazilian conglomerate CSN in a trophy takeover that made global headlines. The consolidated profit of Tata Steel shot up three times and revenue five times, but the celebration was short lived. What no one had expected was the worldwide downturn of FY09 and the subsequent steel slump which ravaged Corus, by then renamed Tata Steel Europe (TSE). Every year, TSE's financial health deteriorated, its cumulative losses (excluding exceptional income) rising to Rs 48,245 crore in 10 years. The large loans taken for its acquisition had to be serviced. The losses were bridged by cash flow from Tata Steel's domestic operations.

Even a last-ditch effort for a merger with German steel giant Thyssenkrupp AG - which had been two years in the making - came undone in May-June 2019 after the European Union anti-trust authority denied permission, maintaining it would be monopolistic and push up steel prices. The joint ventures, suggested by Cyrus Mistry during his short tenure as Tata Group chairman, and pursued by Chandrasekaran, along with Tata Steel Managing Director T.V. Narendran and TSE CEO Hans Fischer, would have absorbed TSE's debt of around ???2.5 billion - a little more than one-fifth of Tata Steel's total debt - had it materialised. "It is obvious that in Europe we have limited options because Thyssenkrupp was the best option in many ways," Narendran told media when the merger was called off. But Tata Steel will continue to look for another partner, preferably one outside the Euro zone.

Around 38 per cent of Tata Steel's annual production of 27 MT came from overseas in FY19. But its current strategy is aimed at dispensing with its overseas acquisitions and focus on the domestic market. Its investments in South-East Asia, which, too, had belied expectations, are waiting for a buyer. The company acquired NatSteel, Singapore in 2004, and Millennium Steel, Thailand in 2006. Both struggled to report profits. In January 2019, it agreed to sell 70 per cent stake in the combined entity to China's state-owned HBIS Group for $327 million, but the deal fell through. "We will continue our efforts to make the European business cash-neutral or cash-positive," said the company earlier. "We're chasing a target of reducing debt by $1 billion."

Chandrasekaran recently said that the Indian entity cannot keep on funding the mounting losses at the UK business. He said that the Port Talbot steelworks in Wales, one of the largest in Europe, should become self-sustainable. The company announced up to 3,000 job cuts last year in Europe. Tata Steel has cut its planned capital expenditure from Rs 12,000 crore to Rs 8,300 crore because of the slowdown.

In the domestic market, Tata Steel has remained aggressive despite its debt, no doubt because of control over raw material supply. It has captive mines for all the iron ore it needs, and about 30 per cent of its coking coal requirements. It is building a steel plant at Kalinganagar, Odisha, of which the first phase of 3 MT was completed in 2016 at a cost of Rs 22,000 crore. The second phase, which will raise capacity to 8 MT at a capital expenditure of Rs 23,500 crore is under way. It has also been bidding for stressed assets that went up for sale through the insolvency court.

The acquisitions - Bhushan Steel and Usha Martin - further increased debt. Bhushan Steel, renamed Tata Steel BSL, which had profits of Rs 1,713 crore in the last fiscal has posted a loss of Rs 504 crore in the third quarter of FY2020 on revenues of Rs 5,038 crore. But profitability of Indian operations of Tata Steel remains high, and with it the hope of bringing down debt. On a standalone basis, the Indian business posted a profit of Rs 10,533 crore on operational revenues of Rs 70,610 crore in FY19. However, consolidated profit declined to Rs 9,098 crore because of losses overseas. It posted Rs 1,229 crore consolidated net loss in Q3FY20 on lower steel prices. The net profit from India operations was Rs 1,194 crore, down 47 per cent.

Limping Jaguar

Neither Jaguar nor Land Rover, despite being iconic brands had much commercial success under previous owner, Ford Motor Co. which lost $1 billion on the two units in 2008. There was a turnaround soon after the acquisition by Tata Motors. The combined unit was made profitable in just two years, thanks to a crack team led by CEO Ralf Speth, who announced retirement recently. In FY2011, JLR had profits of ?1.1 billion and was the second-largest contributor to the group's total profits until FY2016. This was at a time when the domestic operations of Tata Motors was posting losses. Between 2010 and 2018, JLR sales grew over 200 per cent as it launched a range of successful new models. A slowdown in the Chinese and to a lesser extent, European luxury auto markets starting 2018, triggered JLR's rapid descent.

In FY2019, China sales tanked 34.1 per cent, while in Europe (barring the UK), they fell 4.5 per cent, leading to a mountain of unsold cars for JLR and an investment write-off. This included a humongous 'impairment charge' - a permanent reduction of book value - of Rs 27,838 crore in its financial results for FY2019, which resulted in a consolidated net loss of Rs 28,826 crore. Just the previous year, it had earned a profit of Rs 8,989 crore. China accounted for 13.7 per cent of JLR's revenue in FY2019. The Indian business (mainly passenger vehicle and commercial vehicle) improved performance and posted a profit of Rs 2,021 crore in FY2019, compared to a loss of Rs 1,035 crore in FY2018.

"It (JLR) faced headwinds from external factors, including slowdown of sales in China and Europe, along with internal factors of high fixed cost, dealer network profitability and high investment leading to cash outflows," Chandrasekaran said in the last annual report of the company. In October 2018, JLR announced a plan to cut costs and improve cash flows. In January 2019, it announced the slashing of 4,500 jobs worldwide. However, Tata Motors' domestic business has got a new fillip with the launch of several new models, but the momentum has failed to sustain of late.

The China slowdown is attributed to many factors - the trade conflict with the US, changed regulations on auto use and high household debt. Europe sales are said to have been affected by new emission norms, reduced demand for diesel cars and worries over Brexit. With the JLR reversal, the net debt of Tata Motors' automotive business rose to Rs 28,393 crore in FY19, of which JLR's share was Rs 6,500 crore. The rest of the gross debt - Rs 1,06,175 crore in FY2019, but offset by cash balances and investments of Rs 41,782 crore to reach a net Rs 64,393 crore - came from its vehicle finance company.

Tata Motors, however, insists the situation is under control. Tata Motors' debt overhang forced Tata Sons to infuse fresh equity of Rs 6,500 crore, besides Rs 3,500 crore financing through external commercial borrowings, to meet repayments and working capital requirements. The gross debt of the company - which includes Indian automotive operation, JLR and Tata Motors Finance - stood at Rs 1,28,675 crore in December 2019. The net debt of the automotive business in the December quarter is at Rs 45,376 crore.

Business in China showed signs of revival with JLR registering 24.3 per cent growth in retail business during the December quarter. The British company delivered cost and cash savings of ?2.9 billion, ahead of schedule, which envisaged saving ?2.5 billion by March 2020. "We are extending project charge with focus squarely on profit and loss items and it will have a target of delivering further ?1.1 billion of cost and cash savings by March 2021," says P.B. Balaji, Group Chief Financial Officer at Tata Motors.

The Indian business was free cash flow positive for the last two years and after facing a challenging first half of the year, has turned cash flow positive from the third quarter, says the company. "We expect to continue to drive improved profitability of our passenger vehicle business with the launch of a fully refreshed exciting range of BS VI ready products and electric vehicles," it says.

How are Others Faring

Debt is also a concern for Tata Communications, Indian Hotels Company and Tata Chemicals, while Titan, Voltas and Tata Global Beverages are cash-surplus. Tata Chemicals' debt rose 26 per cent in FY19 to Rs 1,939 crore. For Indian Hotels Co, acquisitions in New York and San Francisco have proved to be trouble spots. Its US subsidiary, United Overseas, has been loss-making over the last three years, though losses have been reducing - from Rs 267 crore in 2016/17 to Rs 120 crore the following year to Rs 49 crore in FY19. "The net debt of the company has been reduced by half in the last four years," said the company. The losses of the group's aviation firms rose in FY2019, with AirAsia India's net loss widening four times to Rs 671 crore and that of Tata SIA (operating as Vistara) nearly doubling to Rs 831 crore. Tata Sons holds a 51 per cent stake in both.

Tata Sons, the holding company, had standalone debt of Rs 27,587 crore in March 2019 as against Rs 18,142 crore in the previous year, while the finance businesses - Tata Capital and Tata Motors Finance - had over Rs 1 lakh crore borrowings on books.

Lone Rockstar

Only one Tata company continues to soar. The entire group is now over-dependent on TCS, which has been the biggest Indian IT player for decades and is also India's second most-valued company after Reliance Industries. Watch and jewellery maker Titan is the second most-valued company in the group at over Rs 1 lakh crore, though it's been hit by slowing consumption.

According to rating agency ICRA, TCS accounted for 79 per cent of the market value of the group's quoted investments. The 1:1 bonus issue by TCS in June 2018 and its buyback in September 2018 brought Tata Sons a windfall of around Rs 22,500 crore in buybacks and dividend income in 2018/19.

In 2017, too, Tata Sons had earned Rs 24,760 crore from TCS by tendering promoter shares in a buyback and through dividend. It was these funds that Tata Sons used to settle Tata Tele debt and saving it from earning the tag of being the Tata Group's first bankrupt company.

In the third quarter of this financial year, the TCS board has recommended an interim dividend of Rs 5 per share, taking the total dividend in the nine months until December at Rs 55. It translates into over Rs 24,000 crore returned to shareholders, majorly Tata Sons, which holds 72 per cent stake in the IT bellwether.

In a recent New Year message to employees, Chandrasekaran said the conglomerate is well placed to face challenges in 2020 and is on course to executing its "One Tata" strategy. He wrote, "We are on course and executing our 'One Tata' strategy around the pillars of simplification, synergy and scale." But that may not be enough.

The group needs to tackle the debt burden to be future ready for fresh investments when the economy turns around.

@nevinjl

Copyright©2024 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights: Syndications Today