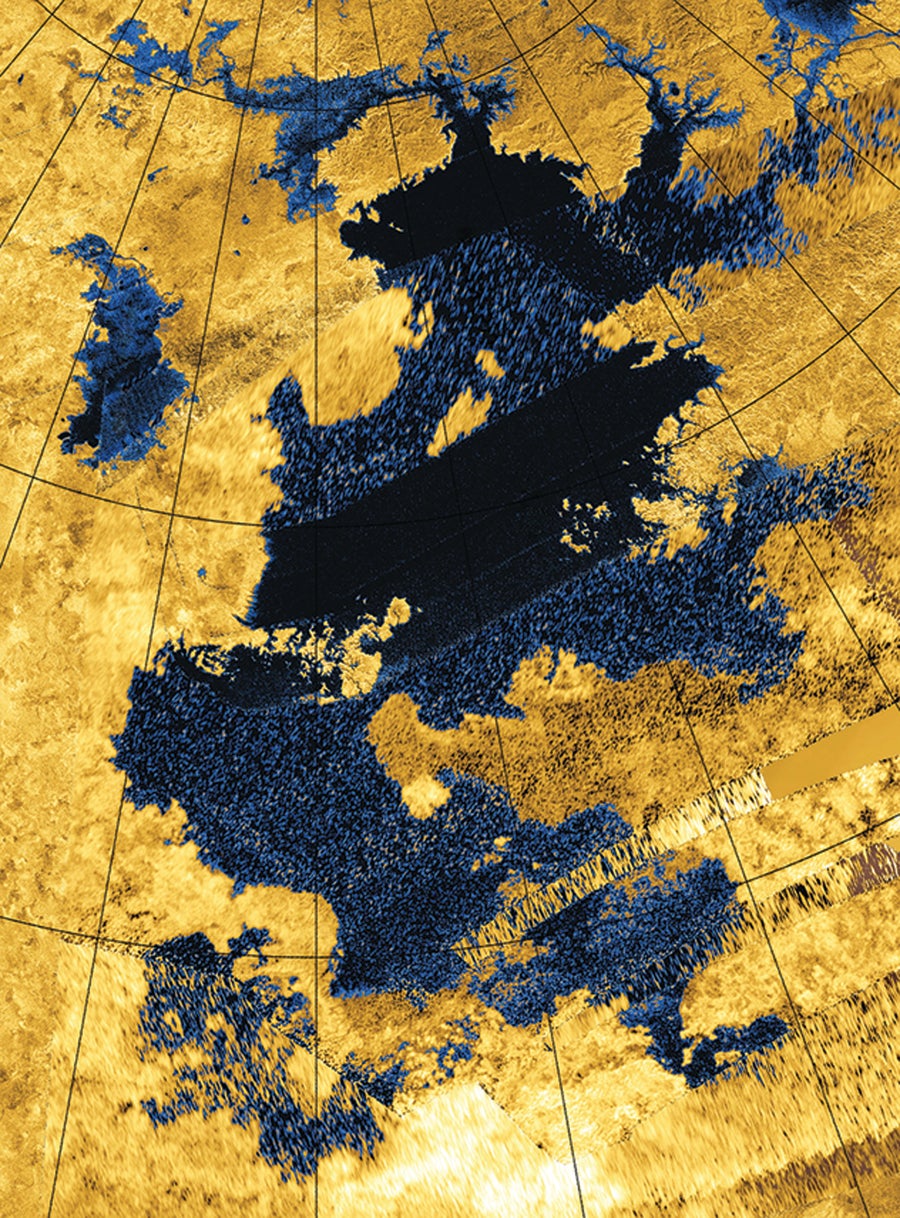

Saturn's moon Titan is the only known place in our solar system, other than Earth, where liquid lakes and seas persist on a world's surface. Scientists are fiercely curious about these features, and now new calculations plumb the impressive depths of Titan's largest sea, Kraken Mare—a frigid blend of methane, ethane and nitrogen.

The finding comes from a fresh analysis of radar scans performed by the Cassini probe as it passed haze-shrouded Titan in August 2014. Using the scans, researchers estimated the depth in a part of Kraken Mare where it was possible to detect a seafloor and in others where it was not. Where a bottom was found, in a large northern estuary, some signals bounced back from the surface while others penetrated the liquid and echoed off the seafloor, says planetary scientist Valerio Poggiali of Cornell University. The echoes indicated this part of the estuary is up to 85 meters deep, Poggiali and his colleagues report in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. But the central and western parts of the sea produced no seafloor echoes, suggesting that central Kraken Mare could be at least 100 meters deep—or even 300 or more.

Kraken Mare. Credit: NASA, JPL-CALTECH, Agenzia Spaziale Italiana and USGS

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“The idea that you can do bathymetry [measure depth] on a moon in the outer solar system is exciting,” says Elizabeth Turtle, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, who was not involved in the new study. The results “are so informative in terms of providing data to understand Titan and to help plan missions there.

The researchers caution that future work might indicate some signals failed to bounce back not because of great depth but because the liquid absorbed more radar energy than they calculated it would. That would suggest their working estimates about composition are off. Based on their calculations, the sea appears to comprise about 70 percent liquid methane, 16 percent liquid nitrogen and 14 percent liquid ethane at a temperature of −182 degrees Celsius. When Cassini swept by, Kraken Mare's surface waves measured just a few millimeters high.

Depth and composition data are vital for engineers designing robotic submarines and other equipment to eventually journey through Titan's lakes and seas, says Steven Oleson, an astronautical engineer at nasa's Glenn Research Center in Ohio, who was also not involved in the study. He and other engineers have put together preliminary designs for such a craft, even though a robotic sub is not currently part of NASA's mission lineup. Understanding Kraken Mare is critical to understanding Titan overall: the sea holds about 80 percent of the moon's surface liquid and covers about 500,000 square kilometers—roughly twice the area of North America's Great Lakes combined.