Francis Ngannou’s Miraculous Journey

On Saturday, MMA's most unlikely champ defends his belt at UFC 270 in what is the culmination of a dangerous 30-year, three-continent road to the Octagon.

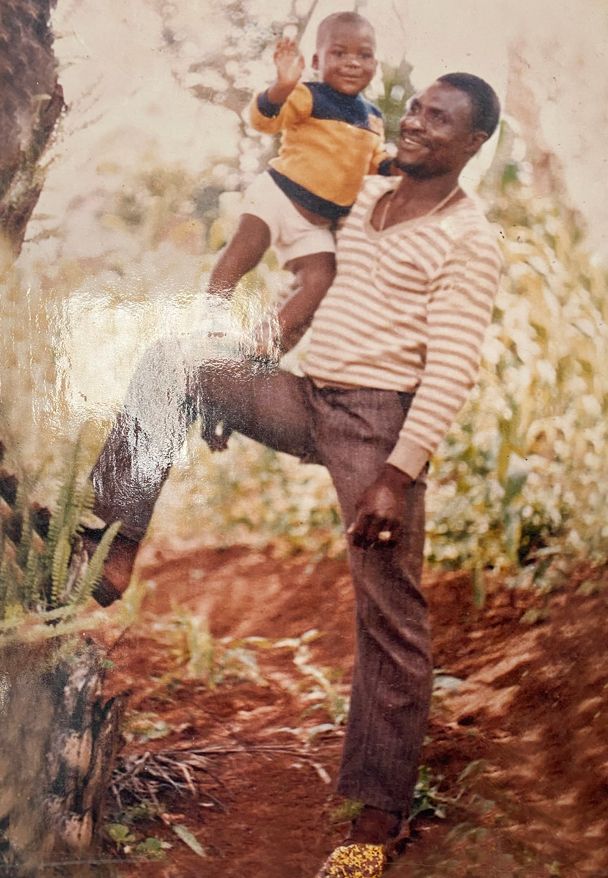

He left his lies floating in the ocean. The symbol on the side of the oncoming boat meant he no longer needed to pretend to be someone else, so he took the fake passport out of his pocket, tossed it from the inflatable raft and watched it recede forever into the endless dark sea. The boat got closer, its symbol growing bigger and bigger, its promise more real. That symbol was an answered prayer. He was, once again, Francis Ngannou, a 26-year-old aspiring boxer from Cameroon; Sambou Mfally, a 40-year-old man from Senegal who existed only on a $30 black-market passport, drifted away. He laughed and told his eight raftmates, "I have never been more proud to be Cameroonian." They were from Cameroon and Mali and Ivory Coast, brought together by chance, and they laughed along with him. This Red Cross boat meant they were headed to Spain, from Morocco, and being Cameroonian in Spain meant he would not be deported. Ngannou was the self-appointed captain of the raft, a flimsy thing built for four, maybe five, probably fewer when the captain is a 6-foot-4, 240-pound Doric column. The fact that he could not swim was not a deterrent. Ngannou was the one who devised the departure plan from Tangier, found the launch spot on the shore of the Strait of Gibraltar and rowed them far enough into the mysterious dark sea -- the Atlantic to the west, the Mediterranean to the east -- to reach international waters, where the rescue call from his flip phone was answered by the Red Cross and not the Moroccan coast guard. Find out how Francis Ngannou's journey to heavyweight champion has spanned eight years and three continents. Produced by Danny Arruda; Edited by Warren Wolcott They boarded the Red Cross boat as victors. They knew the odds. They knew countless bodies had been lost in the 1,200 feet of water beneath them. Each of them traveled remarkable distances -- Ngannou more than 3,000 miles across the Sahara desert, through Nigeria, Niger and Algeria -- hoping for this day. They memorized their cover stories -- Mfally, a construction worker, was married with three children -- with the idea of someday forgetting them. Ngannou had been pulled out of the water six times before, under different circumstances, and either dropped in the middle of the Moroccan desert or temporarily locked in a Moroccan jail. It was a journey of the committed. Their first stop upon reaching shore in Spain was an immigration-detention center -- another jail -- but Ngannou didn't care. Asylum was all but guaranteed for a newly proud Cameroonian, and jail was a temporary inconvenience, far more appealing than living in fear as someone else in the forests of Morocco. The moment Ngannou stepped on European soil, the dream that had been latent for so long was suddenly real. He knew how the system worked; he would serve his two months and be released to the custody of a foundation that helps African refugees. From there, he would head further north still, maybe to Germany, and find a gym where he could go about the long-stalled business of becoming the heavyweight boxing champion of the world. The guards tried to break him, to get him to admit to an accusation or agree to a story that would ruin his hopes for asylum. Their job was to frustrate him, but he'd come too far to fall for such amateurism. He'd withstood far worse. Throughout his 14-month journey, whenever he doubted himself and thought about heading back to his village, he repeated the words that kept him going. "Never underestimate somebody who has hope." This was hope repaying its debt. "My father was the example for me of what not to do," Ngannou says of his father, Emmanuel Fosso, who died in 2001. "I think that was the best thing that ever happened to me because if my dad wasn't what he was, I could have been what he was." Courtesy Francis Ngannou BATIE, CAMEROON. 6 YEARS OLD. 1992. The little boy's parents divorced when he was 6, an event he considers the end of his family. Ngannou moved from house to house, from village to city, from relative to relative. In the years that followed, he learned a lot about his father, Emmanuel Fosso, known in the village of Batie and beyond as a violent man and a ruthless street fighter, someone who would challenge four or five gang members and whip them all. Whenever a stranger asked Francis Ngannou his name, he could see the recognition -- oh, Emmanuel's son -- fall across their faces. Francis, his four siblings and his mother eventually found something resembling stability with his grandmother. She lived in the one-room brick house with the red dirt floor that sat a few yards away from the smokehouse, a separate building that contained the kitchen. The occupancy of the house varied, depending on which cousins, aunts or uncles needed a place to stay. He remembers as many as 20 and as few as six, the number determining how many slept inside and how many out. He changed schools often and always seemed to leave one for another as soon as he had made a new friend. Poverty was a physical presence. He rarely brought lunch to school and when classmates would offer to share he'd refuse. At some point, they would expect him to reciprocate. The teacher would write a note on the board and he couldn't copy it because he couldn't afford a pen or paper. The teacher would get frustrated and kick him out of the classroom. He would try to explain. "I don't have a pen," he would say, but they interpreted it as insolence. The 60 children in the classroom would laugh as he walked down the rows and out the door; the embarrassment was overwhelming. On the days he wasn't sent home, his hunger often sent him in search of food before class ended. The little boy measured time by how many years he had to wear the same shoes. There was the two-year stretch of wearing the clunky ones with the rubber soles so thick they made playing soccer -- the sport of choice in the village -- difficult. Add in a layer of mud from the red dirt and it was like running with ankle weights. He was not a particularly good player -- the shoes saw to that -- and he often wasn't chosen to play because everybody chose their friends. He, in his own words, was "nobody's friend." He was 9 years old, his brother 11, when they began working in the sand mine for $1.90 a day. Water was diverted from streams to run down the sides of the mountains, and men would straddle the steep slopes, their stances like surfers, and use metal bars to chip away at the soil and send it down into the valley below. The water would mix with the dirt and sand and wash it down the hill, separating it along the way, and the two boys would shovel the sand into piles so older, stronger men could shovel it into the back of dump trucks. He was too young to be doing man's work, but the monotony allowed his mind to conjure all sorts of fantastical scenarios. The United States hosted the World Cup in 1994 and sparked an obsession with America. He gave himself a nickname: American Boy -- and wrapped himself in it like a blanket. The following year, he had to practice his signature for a school assignment. He and his classmates would soon be moving on to an upper school, and they would need student identification cards, and those cards required a signature. Around the village, Ngannou was Francis and sometimes Francisco, and he played around with his signature until he settled on signing San Francisco Ngannou, a practice that holds to this day. He knew just one thing about San Francisco: it was in America, and that was enough. His main exposure to the United States was through action movies and the occasional television show. Only twice in his young life did he have a television in his home: when his father brought one home to repair for someone else and when he lived in the city with relatives and they had a set that was about the size of a paperback. But as luck would have it, he often was sent to the nearest store, a 2-mile walk each way, and the shopkeeper had a television with a VCR and a similar taste in entertainment. When a movie played at the shop, Francis would stay as long as possible, even when he knew a spanking awaited his return. And every Saturday at 4 p.m., there was magic: a Cameroonian television station played reruns of "Knight Rider," translated into French. Ngannou's mother and grandmother, knowing his affinity, held it over him like a sword. "Remember Saturday?" they would ask/threaten whenever he even thought about acting up. Bad boys didn't get to visit the neighbor's house to watch the crime-fighting exploits of KITT, the world's most famous and heavily modified Trans Am, so Francis always tried to be good. The small screen gave American Boy a glimpse of America. The land of David Hasselhoff and muscle cars and San Francisco, wherever and whatever that was. He heard people in the village dream of France, with its familiar language and thriving immigrant community, but he had other ideas. Whenever he summoned the courage to tell someone in the village about his dream of America, he always heard the same thing: "Bro, you dream big." He could always find a hint of mockery in those words, but he learned to ignore it. Someday, American Boy would make it to America. He would go there to lose his pain. Ngannou dubbed himself the "American Boy" as a child, his vision of the U.S. filtered through American television shows, like "Knight Rider," translated in French. Peter Yang for ESPN PARIS. 26 YEARS OLD. 2013. Ngannou arrived unannounced in a Paris boxing gym, 10 weeks after boarding the Red Cross boat in the Strait of Gibraltar and one day after arriving in this new city. He waited for a part-time coach to finish a class and told him, "I have no money. I got here yesterday. All I want is a place to train because I want to become a world champion." Didier Carmont looked across the check-in desk and saw someone tall and regal, with muscles built by years of shoveling in the sand mine. Ngannou's physical stature was obvious, but there was something about the way Ngannou presented himself -- dignified despite his life's indignities -- that kept Carmont from dismissing him and his grand design. Ngannou considered Paris a stopover, as far as he could travel on the 50 euros he was provided by a Spanish agency set up to assist migrants from sub-Saharan Africa. There was no boxing community in Paris, no viable pipeline to the kind of fame he sought. He got there by taking a train from Madrid and securing rides through the same kind of black-market network that got him the Sambou Mfally passport. He scouted a place to live, found a covered parking lot and set up camp in a stairwell. "The parking lot was so nice," he says. "I didn't even feel homeless." It was June 9, 2013, and he was wearing the same sneakers he was wearing when he left Cameroon on April 3, 2012, 14 months earlier. “Everywhere that the sun sets is your home at that moment.” Ngannou was wary, slow to reveal the details of his personal story and fearful of allowing anyone to get too close too soon. Carmont's generosity relieved some of Ngannou's loneliness and gave him a glimpse of a possible community. Carmont bought him his first smartphone and a new pair of shoes. Ngannou had been working out at the gym and living in the parking lot for about two months when Carmont met him at a Metro station and took him to a building near the Picasso Museum. They entered a one-bedroom apartment, and Carmont began pointing out its features. "Why are you telling me this?" Ngannou asked, anxious to get back to his part of the city before the public showers closed. Carmont finished his tour by giving Ngannou the key to the apartment and telling him he could stay there rent-free for two months. Ngannou was unaccustomed to being treated with such generosity, and one question bounced around his brain as he walked through the apartment holding the key. "Why is he doing this?" Eventually, the skepticism dissolved. "He saw me as a man," Ngannou says, "not an athlete." Boxing was the perfect outlet. "Not only could I prove I'm not worthless," he says, "but I could save my reputation and make money at it. Instead of fighting for free, I would fight for something." But in Paris, reality intruded. Ngannou was 26, homeless and broke. The path to professional boxing at his age, in a country with little in the way of opportunity, was difficult to envision. "You need to make a living," Carmont told him, "And you're not going to make a living as a boxer." Carmont suggested MMA. "What is MMA?" Ngannou asked. "Mixed martial arts. "Yes, cool -- mixed martial arts," Ngannou responded. "But what is that?" Carmont explained it as simply as he could: "Wrestling, grappling, striking." Ngannou waved him away. "Bro, leave me alone," Ngannou said playfully. "I just want to do boxing. You know? Straight-up boxing. The noble art, like Mike Tyson." Mixed martial arts was never a part of the dream, and the idea of becoming world champion in a sport he didn't know existed seemed radical in the extreme. But Carmont kept at it, gently but persistently. "He would always find a moment to sneak that MMA idea in," Ngannou says. Carmont told him about a place called the MMA Factory that would be happy to have him. "Just give it a try." Two months later, the boxing gym closed for the month of August, and Ngannou conceded, just to stay in shape. He went to the MMA Factory to introduce himself to the coach, Fernand Lopez, and was met by an employee whose eyes widened as Ngannou got closer. "Oh, s---," he said. "You are one big motherf---er. Fernand will be happy to see you." Visiting his village as a champion brought Ngannou joy. "They were feeling it, feeling part of it," he says. "They were like, 'Oh, it is possible. You can make it.'" Peter Yang for ESPN FROM CAMEROON TO MOROCCO. 25 YEARS OLD. 2012. He was made to feel worthless so many times that he grew to believe it. His schooling was constantly interrupted by his deprivation; there was never enough money for supplies or the government fees, so working in the mine allowed him to earn money and avoid the shame that followed him around at school. And by 13, he was able to do the work of a grown man. He scooped the sand from the red earth and tossed it over his head into the dump trucks in one fluid motion, momentum and leverage overcoming a lack of size and strength. His confidence grew, and he made a conscious decision to stop thinking of himself as a victim. "What did I do wrong to deserve this?" he asked himself repeatedly. The answer, every time, was nothing. Everything he had, he realized, he had earned himself. The shoes on his feet, the shirt, the pants -- he earned them. A shovel at a time, $1.90 a day, day after day. He knew the value of hard work and the people who looked down on him did not. "Whether my shoes are two years old, I know the value of those shoes," he says. "Whether it's the torn shirt I'm wearing, I know the value of that." He quit school at 17 and began to plot his departure from the village. His pay rose to $2.50 per day and he saved as much as he could. He began boxing at a local gym, where the training and the surroundings were rudimentary. The work in the mine seemed to multiply his muscles, and he shot up to 6-4, but whenever he voiced his plan of leaving Cameroon to go to America and become the heavyweight champion of the world, he got the same reaction he had years before: You dream big, bro. Ngannou, 16-3, defeated Stipe Miocic, 20-4, at UFC 260 in 2021. On Saturday, he'll meet Ciryl Gane, a former Paris training partner, in the Octagon at UFC 270. Jeff Bottari/Zuffa LLC/Getty Images Years passed and Ngannou remained in the village. He turned 20, the age his hero, Mike Tyson, became heavyweight champion, and then 22, the age Muhammad Ali did the same. Finally, on April 3, 2012, 25-year-old Francis Ngannou said goodbye to his family and set out to pursue a new life. The journey was carved into his psyche: first Morocco, then the treacherous eight-mile passage across the narrowest body of water separating Africa and Europe. It took Ngannou three weeks to travel 3,000 miles to Morocco. There was an underground network of people who would help, for a fee, and he spent his meager funds accordingly. He paid for car rides and walked hundreds of miles. He was welcome in some countries and not in others. Desert, forest, mountain -- the earth became an opponent to outwit and conquer. "Everywhere that the sun sets is your home at that moment," he says. In Morocco, he did his best to live in the shadows. Before entering a store, he would stand outside and find all available exits, just in case. He learned to read body language and clothing to identify undercover cops, who always responded to eye contact with a dead-eyed stare. His first attempt at crossing into Spain ended when the captain saw a Moroccan coast guard boat approaching, dropped the oars and slipped into the water. Ngannou watched, with a mixture of horror and disbelief, as the captain swam from one side of the raft to the other, hoping to avoid detection long enough to reclaim the raft after Ngannou and two others were detained. But since the call reporting the raft specified four passengers, the coast guard waited and captured him. His first three attempts failed, and each resulted in him being dropped off in Western Sahara by Moroccan police without food or water. Before he tried again, he sought out the black-market passport and became Sambou Mfally, the 40-year-old construction worker from Senegal. (This was nothing new: he was Malian during his trek across Algeria.) "Oh, it was cool to be Senegalian, bro," he says. "I was all Senegalian." Then the fourth attempt failed, and then the fifth, and then the sixth. Each time a raft pushed off from the shore, the adrenaline rush of possibility overcame the fear of the endless black sea. He couldn't feel anything until he got caught, and then he felt everything: the empty stomach, the wet, the cold, the prospect of starting over. The hope, so powerful just minutes before, left his body like a fever breaking. It was enough to make a man, even one as strong-willed as Ngannou, reconsider his choices. But every time he thought about heading back to the village in Batie, he realized there was nothing back there for him but more pain, more mockery. You thought you were better than us and now look at you. He left everything behind, sold everything he owned -- even his bed! -- and to return would be an admission of failure. Maybe he'd have to ask his brother for money, beg for a place to sleep, listen to those who stayed behind and reveled in taunting the dreamers who thought they were better than the village. Quitter, they would say. He knew it because he'd heard it thrown at others so many times before. But on cold, rainy nights in the forest -- the thinnest plastic providing cover, logs arranged on stones the only layer separating him from the muddy earth -- the temptation to return to his village, to the familiarity of his previous life, could be strong. "But that means you give up," Ngannou says. "That means you no longer have hope." Call him: American Boy, San Francisco Ngannou or even the "baddest man on the planet." But you can't call Ngannou a quitter. Peter Yang for ESPN PARIS. 27 YEARS OLD. 2013. At first, he avoided the conversations at the gym. The MMA fighters at the MMA Factory in Paris were immersed in the culture, seemingly aware of every fighter and every fight. Names flew at him. Cain Velasquez. Junior dos Santos. Conor McGregor. Knowing nothing of this new world, Ngannou drifted away from the conversations, fearful of exposing his ignorance, then went home and researched the fighters so he could have something to add the next time their names came up. And he had a dirty secret: he didn't understand MMA, but he liked it. It was freewheeling, a little bit wild and really fun. The grappling and kicking reminded him of the action movies that allowed him to briefly escape his childhood. A spinning back kick? Sign him up. He saw it as a diversion, nothing more than a hobby while the boxing gym remained closed. And then he started to get good at it. He had been practicing the sport for less than four months when Lopez, who is also from Cameroon, decided he was ready to make his professional debut. On Nov. 30, 2013, Ngannou fought Rachid Benzina in a Paris event called "100% Fight: Contenders 20." Ngannou was nervous, excited and more than a little confused. He never intended to take the sport seriously, and now here he was, doing it professionally without fully understanding it. It was crazy, sure, but it was also hilarious. In the locker room before the fight, Ngannou tried to remember the rules of his new sport. What should I do? he asked himself. What shouldn't I do? He decided he couldn't bring that kind of indecision into the cage, so he shrugged and told himself, "It's a fight between two people. You can handle that." He won that first fight by submission over Benzina, who never fought professionally again. Just two weeks later, Ngannou fought his second fight -- "100% Fight: Contenders 21" -- and lost by unanimous decision to Zoumana Cisse. It was just one more act of providence Ngannou has learned not to question. Had he won, he would have returned to the boxing gym with a few more euros in his pocket, and MMA would have been just another plot twist to his remarkable life. Instead, the loss, like every other failure in his life, tugged at him like the promise of that distant shore. He couldn't leave it undone. STRAIT OF GIBRALTAR. 26 YEARS OLD. 2013. Ngannou began planning for his next crossing as if it were a military operation. He hung out at cyber cafes in Tangier and hopped on the prepaid internet service computers whenever someone left before their time ran out. He researched tides and swells and surf, wind direction and moon phases. He sought the perfect night: wind out of the south; low, short swells; moonless. He is the captain, the one who will determine departure date and time, the one who will paddle strongest and truest, the one who will -- with any luck -- guide the raft far enough into the Mediterranean to make the call that summons the Red Cross to rescue them and take them to Spain, where a new life can begin. Ngannou chose a night in mid-March. Wind out of the south, smooth surf, minor swell, new moon. Everyone in the group pitched in to purchase the $50 raft they were trusting to keep them alive. When the time came to shove off, Ngannou avoided a run-in with a Moroccan immigration officer and guided the group to a protected cove. He found a slot between rocks just wide enough to inflate and launch the raft. Eight people loaded up, many of them for the first time, their fear wafting in the air, each of them operating on the hope for a better life and a blind faith in their heavily muscled captain. As he pushed off, Ngannou looked at his raftmates and tried to project calm. They needed to see him, first and foremost, as someone with hope. He paddled them beyond the break and quietly into the darkness. For miles around them and 1,200 feet below them, nothing but water. The seas remained calm, the winds light and he allowed himself to think this might be the time. He tried not to think about the six failed crossings, the indignity of the capture, the going back, the starting over. The lights of Tangier grew more distant. Everyone stayed silent. The only sounds were the water slapping the sides of the raft and the paddles breaking the surface of the water. After what felt like an eternity, Ngannou stopped rowing and estimated the distance they'd traveled. He told his raftmates it was time. He saw equal parts excitement and relief in their faces. He punched the numbers into his phone. Ngannou returned to Cameroon in April 2021, a month after knocking out Miocic. He walked through Batie as a hero -- "a superhero," his friend Didier Carmont says. Daniel Beloumou Olomo/AFP/Getty Images LAS VEGAS. 35 YEARS OLD. 2022. Ngannou lives in a two-story house in the great stucco forest of Las Vegas, amid blocks and blocks of identical tract homes. The pool out back is drained, its surface awaiting a refinish. There's a stationary bike and a treadmill in the dining room and an endless supply of UFC-branded water bottles in a cabinet next to the fridge. There are large, framed photographs leaning against the walls, all featuring a championship belt and a smiling champion. He occasionally stands and dribbles a brand-new soccer ball absently -- right, right, left, right -- off a pair of brand-new sneakers. American Boy, in America. One framed photograph hangs in the living room: Francis, probably 2 or 3 years old, with his father, who died in 2001. They are both smiling, Francis wearing white shorts and a blue and gold shirt, his father in slacks and a striped long-sleeved shirt. They appear to be on a trail in the forest, the distinctive red dirt of Cameroon beneath them. His father is tall and lean, his face marked by the same square geometry as his son's. Emmanuel Fosso's right foot rests against the stump of a tree. Francis stands on his father's thigh, his tiny right hand waving to the person holding the camera. The photo has been enlarged, and a yellow tint is creeping in from the edges, fading like a memory. "My whole life, my father was the example for me of what not to do," he says. "I think that was the best thing that ever happened to me because if my dad wasn't what he was, I could have been what he was. But I still love him -- a lot." “It is not the title of UFC champion that makes Francis Ngannou. Francis Ngannou makes the UFC champion. I know everything that I did, I did on my terms.” Those who know him best say Ngannou lives an ascetic life: he trains, he rests, he trains again. He has no family in the United States; his mother was denied a visa twice when she attempted to visit her son and attend a fight two years ago, and Ngannou says, "I didn't like the way it happened. You have a background check, and when they find out you're poor, they know you are [coming to the U.S.] to stay. My mom can't live here, you know? Her friends, her kids, her grandkids -- our whole life is in Africa." One of Ngannou's younger brothers was admitted to UNLV two years ago, but the pandemic has kept him from leaving Cameroon to attend. Ngannou could stand on his roof and see the constellation of lights of the Vegas strip, but they hold little appeal. The little boy from the village and the boy from the sand mine and the young man from the inflatable raft is now the UFC heavyweight champion of the world. To say he got there the hard way is an understatement; after his journey from Africa, he fought five times in Europe before being signed by the UFC, at which point the talent took over and the acceleration began. His first fight was UFC on Fox 17 in 2015, where he fought the opening fight against Luis Henrique in an empty building in Orlando, Florida, on a card that included a prime-time bout between heavyweights Alistair Overeem and dos Santos. Ngannou won. Along the way to his 16-3 record -- including five straight stoppages -- he knocked out two men, dos Santos and Velasquez, whose names he researched after backing away from the conversations in the Paris gym. He also knocked Overeem out cold in late 2017. Something changes in that moment when the latch on the cage door clicks and it's just two fighters and a referee. These are some of the toughest men in sports, and the word fear is the filthiest of four-letter words, but something awfully close to it falls across the faces of the men who find themselves staring across the Octagon at Ngannou. It's not his size so much as the unsmiling, expressionless serenity he exudes as if the prospect of beating their asses bores him. He seems to hover slightly above the overamped, often cultish world of the UFC. He is the rarest of men: elegant in an inelegant sport. May 9, 2020, Jacksonville, Florida, UFC 249: Jairzinho Rozenstruik was the 18th of Ngannou's 19 professional opponents. As Ngannou walked from the dressing room to the cage, his coach, Eric Nicksick, hung back to scan the room and get a sense of the moment. What he saw was Ngannou snapping his fingers -- "like he was going for a stroll in the park," Nicksick says -- and Rozenstruik looking over, seeing the easy confidence and realizing the enormity of what he faced. "You could see the body language," Nicksick says, "and how things changed pretty quickly." Ngannou knocked him out in 20 seconds. He approaches his work almost clinically, walking down his opponents and looking for the most devastating moment to unleash a right hand that holds the unofficial record -- as recorded by the UFC -- for the hardest punch ever recorded, the equivalent of 93 horsepower. (A Smart car, by comparison, maxes out at 80.) He trains in Las Vegas at Xtreme Couture, a gym run by UFC legend Randy Couture, and it's a wild collection of square-jawed, thick-browed, mangled-eared Eastern Europeans, sharp-tongued, tireless women and three hulking heavyweights who get the honor of sparring with Ngannou. On a surprisingly brisk Saturday in mid-December -- Sicko Saturday, as dubbed by Nicksick -- Ngannou works out in the gym's main Octagon, where a sign reading "Human Resources" hangs above the cage gate. Ngannou, whose body appears to have adopted a state of permanent flex, goes about his business unsmiling and expressionless, the path of his punches extending and retracting like a snake's tongue, the muscles in his legs distending as they constrict around a sparring partner's back, the sound of his kicks hitting the pads and echoing off the walls like gunshots. Around the corner is a whiteboard bearing a handwritten message: "Though most relationships end in despair, the temple of gains will always be there." This bit of nihilistic inspiration is attributed to the noted philosopher "Swolezekiel 3:5." A pragmatist among zealots, Ngannou finishes a grueling, nonstop hourlong workout and immediately grabs a jump rope, finds a mirror and jumps for 45 minutes, also nonstop. He appears to derive neither pleasure nor misery from the process. "They're hard practices, and I understand that," Nicksick says. "But I think it's important to draw on those comparisons at times and say, 'Hey, you've been through a lot worse.' He makes that connection right away and you see him just bounce up. 'You're right. No problem. I got this.'" Ngannou is riding a streak of five straight knockouts as he trains for UFC 270's main event against Ciryl Gane, a former Paris training partner coached by Lopez, the man who was happy to see the "one big motherf---er" in the Paris gym. Lopez coached Ngannou through his first 14 MMA fights, and their contentious and public falling out has elicited the kind of discourse more suited to a high school lunch table. The drama began when Ngannou ignored Lopez and Gane as he walked past them in a Madison Square Garden hallway at UFC 268 in November. Since then, Lopez has adopted the role of antagonist/promoter, casting Ngannou as an ingrate and a cheapskate and suggesting that his mother became upset when Ngannou didn't mention her son's influence during a television interview. Ngannou, for his part, believes the UFC is casting him as the bad guy to promote a good vs. evil storyline. Ngannou traversed three continents and navigated life-threatening circumstances to grab hold of his dreams. And everything he did to get this moment, defending the heavyweight title, was done on his terms. Peter Yang for ESPN It's easy to dismiss the talk as the charmless byproduct of a pay-per-view enterprise -- UFC events are called promotions for a reason -- but it might signal a deeper discontent within Ngannou. The fight against Gane will be his 20th MMA fight and potentially his last. Like many other fighters before him, including Nate Diaz and Jorge Masvidal, Ngannou's relationship with the UFC has soured as his profile has soared. The business model, under which the UFC keeps roughly 85% of all revenue and fighters work as independent contractors, has chafed fighters from the beginning. Asked to describe his relationship with Dana White and the UFC, Ngannou says, "Not good, bro. Not good -- because I don't kiss the ring." He has learned the power of his story, and the journey has emboldened him. "They may think I have no options, but I am a free man," he says. "I might be UFC champion, but I have no problem going back to Africa and doing my thing. This is not what defines me. It is not the title of UFC champion that makes Francis Ngannou. Francis Ngannou makes the UFC champion. I know everything that I did, I did on my terms. "There is still a lot there for me as far as the challenge, but it gets ugly at some point, and it's not fun anymore. I didn't want to be a UFC fighter, but it was fun to do MMA. That's what got me here -- fun. The UFC wasn't my dream. I wasn't looking for the UFC. What I'm doing is having fun, so when they take the fun part away, it's not the same thing anymore. I enjoy training, and I'm happy when I think about fights, but when I think about the whole picture -- the whole business -- it's exhausting." He pauses for a moment and goes back to dribbling the soccer ball. It echoes off the high ceiling as he recalls the moments in the locker room last March before he knocked out Miocic to become champion. His mind drifted to Batie. He thought about his mom in front of the television, her stress levels rising. He thought about the cousins and uncles and aunts who spent time in that house with the red-dirt floors and rolled their eyes at the dreamer and his wild dream. What are they thinking now? He also thought about those he doesn't even know, the ones who might envy his situation but fear the journey. It's not about just me anymore, he thought. This is something bigger. All of them remember the original dream: heavyweight boxing champion of the world. It nags at him like that loss in his second fight, one more thing left undone. He is 35, older in some ways, younger in others. Do dreams -- big dreams, bro -- ever truly expire?

Ngannou returned to Cameroon last April, a month after knocking out Miocic. He walked through Batie as a hero -- "a superhero," his friend Carmont says. The champion recognized nearly everyone, the guys who dismissed his dreams, the snickering classmates and the unsympathetic teachers. He went back to the mine and stood on the hillside with a pry bar and sent great chunks of earth crashing into the valley below, not because he had to but because he wanted to. He stood in the back of a truck with his family and held the belt aloft as the people of the village danced and clapped. "They were feeling it, feeling part of it," he says. "They were like, 'Oh, it is possible. You can make it.'" From his vantage point in the bed of the truck, Ngannou looked directly into a past he sought to escape and was surprised to see it looking back at him, lifting him on its shoulders. And on that day, he felt something he'd rarely felt in that village: unbridled joy. For once in his life, after everything that had come before, it finally felt like enough. Styling by Olori Swank; Grooming by Hee Soo Kwon, @heeezooo/The Rex Agency; Production by Suzette Kealen and Marco Mavridis/Crawford & Co.; gold suit by Dolce & Gabbana; watch by Jacob & Co; print suit by Dolce & Gabbana; shirt by Braydon Alexander; lapel Pins by Gucci, Chanel; hat, necklace & rings: Francis' Own