Fifty years ago, the Beatles entered their final year as a working rock 'n' roll band. And in the ensuing decades, the reasons for their eventual disbandment have been debated ad nauseam. Was it Yoko Ono's constant presence in the studio? Paul McCartney's increasingly controlling nature? John Lennon's rage to break free of the partnership that he had brokered with McCartney after their meeting in a Liverpool churchyard in July 1957? Or simply Ringo Starr's apathy or George Harrison's need to strike out on his own and fulfill his promise as a songwriter in his own right?

In truth, although each of the above was a contributing factor, by January 1969 a much darker force had made its presence known in their world. During that fateful year, the Beatles suffered, as so many families do today, from the daily pain and bewilderment of an opioid addiction.

Although we have slowly come to recognize the opioid epidemic as the Western world's most perilous health crisis, we have yet to turn the corner in terms of stemming its tide. In fact, things are getting worse. The National Safety Council recently reported that opioid addiction has become so pervasive that Americans are now more likely to die from an opioid overdose than an automobile accident.

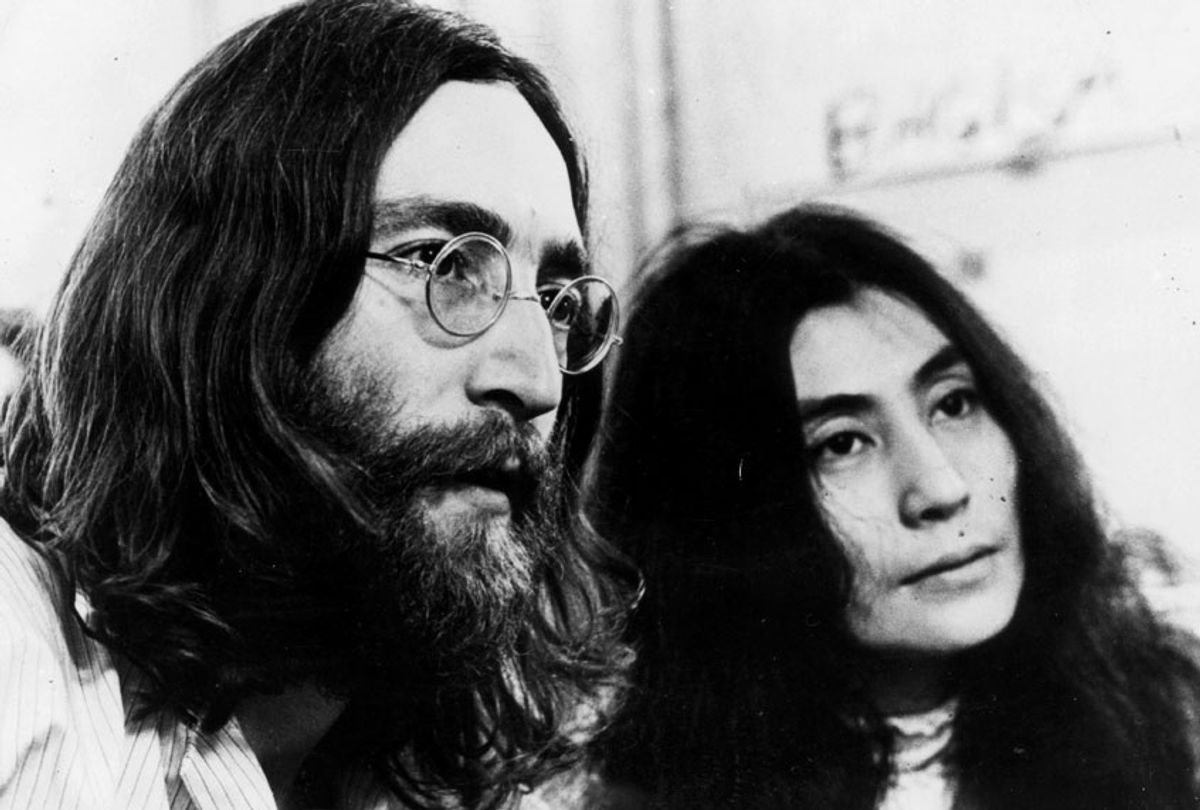

In early 1969, the faces of heroin addiction for McCartney, Harrison and Starr — three quarters of rock music's Fab Four — were Lennon and his wife Ono. With The White Album lording over the global record charts, the Beatles were the biggest act in the world by a wide margin. By this time, they had challenged themselves to "get back" to their roots, strip away the high-gloss production of LPs like "Revolver" and "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band," and find new levels of greatness.

And for the most part, they would succeed. The "Get Back" project would come in for a rough landing with the band's triumphant Rooftop Concert on January 30th, and they would record a spate of new classics that summer. That fall, they would release "Abbey Road," their magisterial swan song. While heroin had infiltrated their midst, they managed — for a time, at least — to overcome the drug's insidious nature. The Beatles, after all, were that good.

As history has demonstrated resoundingly, the band members were no strangers to drug experimentation. They had become veteran pill-poppers during their days in Hamburg's seedy postwar clubs, seeking out amphetamines to increase their stamina during those long nights on the Reeperbahn. Later, marijuana would come into their lives by way of Bob Dylan in August 1964. In the coming years, they would make international headlines for tripping out on LSD, and in the summer of 1968, as the Beatles had toiled in the studio to record The White Album, McCartney would engage in an extended dalliance with cocaine.

However, Lennon's addiction left his bandmates in a state of alarm. By the advent of the "Get Back" sessions, Ono openly joked about taking heroin being the couple's form of exercise. "The two of them were on heroin," said McCartney, "and this was a fairly big shocker for us because we all thought we were far-out boys, but we kind of understood that we'd never get quite that far out."

Lennon later claimed that the couple's addiction developed in the wake of a hashish raid on his Montagu Square flat by Detective-Sergeant Norman Pilcher's notorious drugs squad. Lennon attributed Ono's mid-November 1968 miscarriage to the raid's aftermath, later remarking that "we were in real pain" after the loss of their baby. Yet at other times, he would attribute his flirtation with heroin to his bandmates' refusal to accept Ono as their equal, claiming that they began to snort heroin "because of what the Beatles and their pals did to us."

Love the Beatles? Listen to Ken's podcast "Everything Fab Four."

But in truth, Lennon's experimentation with the drug had begun much earlier—most likely, during Ono's summer 1968 exhibition at the Robert Fraser Gallery. "I never injected," he liked to say. "Just sniffing, you know." But as journalist and Lennon confidant Ray Connolly observed, Lennon "rarely did anything he liked by halves. Before long, heroin would become a problem for him."

As anyone with a friend or relative who suffers from substance abuse knows all too well, the addict's reasons for imbibing their drug of choice are often multitudinous and frequently hurtful. The brutal truth is that they simply must have it. Whether it be alcohol or heroin—the user is powerless in the face of the drug's delectable, unerring pull.

When the Beatles finally got to the business of recording "Abbey Road," Lennon's participation was delayed by a harrowing automobile accident in Scotland that left him and Ono briefly hospitalized and riddled with stitches. When he finally joined the other Beatles towards mid-July, he had a bed from Harrods installed in the studio to allow Ono to convalesce within easy reach.

Not surprisingly, the accident's aftermath resulted in heroin being the couple's go-to salve. Indeed, by this juncture, Lennon's mood swings and absenteeism—the ups and downs of his erratic, unpredictable behavior—were likely the result of their protracted heroin use. As music historian Barry Miles later wrote, "The other Beatles had to walk on eggshells just to avoid one of his explosive rages. Whereas in the old days they could have tackled him about the strain that Yoko's presence put on recording and had an old-fashioned set-to about it, now it was impossible because John was in such an unpredictable state and so obviously in pain."

Years later, American actor Dan Richter, a friend of Ono's, recalled making his way inside EMI Studios to provide Ono with the Lennons' latest fix. "It felt weird to be sitting on the bed talking to Yoko while the Beatles were working across the studio," said Richter. "I couldn't help thinking that those guys were making rock 'n' roll history, while I was sitting on this bed in the middle of the Abbey Road studio, handing Yoko a small white packet."

After the Beatles' last photo session at Tittenhurst Park on August 22nd, 1969 — in fact, the final occasion in which all four Beatles would be together in person — the couple resolved to kick the habit once and for all. Ono sought out the help of Richter, her supplier, to assist them in breaking free of the opioid. "We were very square people in a way," said Ono. "We wouldn't kick it in a hospital because we wouldn't let anybody know. We just went straight cold turkey. The thing is, because we never injected, I don't think we were sort of — well, we were hooked, but I don't think it was a great amount. Still, it was hard. Cold turkey is always hard."

Today, the UK's National Health Service has much to offer in terms of maintenance therapy and detox programs. But in August 1969, opioids were scarcely on the NHS's radar. To Lennon's mind, the only means at their disposal was going "cold turkey," which denotes heroin's abrupt cessation. Desperate to wrest himself free, Lennon reportedly ordered Ono to tie him up to a chair. For some 36 hours, he roiled in pain as he attempted to rid the drug from his system.

In an effort to memorialize his recent experience trying to shake his heroin addiction, Lennon composed "Cold Turkey," a song that illustrated the excruciating throes of heroin withdrawal in brutal detail: "My feet are so heavy / So is my head / I wish I was a baby / I wish I was dead." But the composer's triumph over the drug would be dishearteningly short-lived. By the time he debuted the song for Dylan a few days later, he was snorting heroin yet again. Lennon later recalled that he and Dylan "were both in shades and both on fucking junk." He knew that it would take much more than a chair and a rope, admitting that "I was nervous as shit."

It would take several more attempts for Lennon to beat the drug. To his great credit, the musician lived his life transparently, sharing his trials and tribulations across numerous interviews. In September 1980, he lamented that back in 1969 the BBC banned "Cold Turkey" from the radio airwaves "even though it's antidrug." Even then — long before our contemporary opioid crisis took flight — Lennon intuited society's inability to understand, much less combat addiction. "They're so stupid about drugs," he exclaimed. "They're not looking at the cause of the drug problem: Why do people take drugs? To escape from what? Is life so terrible? Are we living in such a terrible situation that we can't do anything without reinforcement of alcohol, tobacco? Aspirins, sleeping pills, uppers, downers, never mind the heroin and cocaine—they're just the outer fringes of Librium and speed."

While we understand far more about the nature of addiction and drug treatment than Lennon could possibly have dreamt in the autumn of 1980, we are lost nevertheless in a health crisis that continues to surge. The striking similarities between the Fab Four's predicament and today's devastating health crisis remain indubitably clear. As we stumble forward as a culture nearly five decades after the Beatles' disbandment, it is genuinely staggering to recognize how far we still have to go.

Shares