- India

- International

National security, at the cost of citizens’ privacy

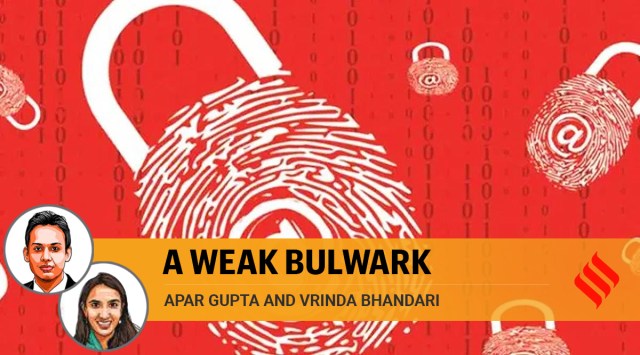

🔴 Apar Gupta, Vrinda Bhandari writes: The JPC report and the Data Protection Bill, 2021 protect the government instead of the personal data of Indian citizens

Quite simply, what good is a data protection law if it does not regulate mass surveillance projects like the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems (CCTNS), the Central Monitoring System (CMS) or the National Intelligence Grid (NatGrid)? (File)

Quite simply, what good is a data protection law if it does not regulate mass surveillance projects like the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems (CCTNS), the Central Monitoring System (CMS) or the National Intelligence Grid (NatGrid)? (File)After two years of deliberation, the Parliamentary Joint Committee on the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (JPC) tabled its report this week. The recommendations are appended with a redrafted version of the law, named the “Data Protection Bill, 2021”. The constitutional principle of a data protection law has been set out in the Justice K S Puttaswamy judgment by the Supreme Court of India that reaffirmed the fundamental right to privacy. Justice D Y Chandrachud stated that the “creation of such a regime requires a careful and sensitive balance between individual interests and legitimate concerns of the state.” There are three clear reasons why the Data Protection Bill, 2021 tilts clearly in favour of the central government and against the fundamental right to privacy.

The first noticeable feature of the Data Protection Bill, 2021 remains a questionable design choice by which it evades any provisions for surveillance reform. Surveillance reform was consciously omitted by the Justice B N Srikrishna committee that released the first draft of the Personal Data Protection (PDP) bill in 2018. However, even then it stated, “no general law in India today authorises non-consensual access to personal data or interception of personal communication”. Quite simply, what good is a data protection law if it does not regulate mass surveillance projects like the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems (CCTNS), the Central Monitoring System (CMS) or the National Intelligence Grid (NatGrid)? Not only does it fail to improve Justice B N Srikrishna’s draft law, the Data Protection Bill, 2021 makes it worse. It inserts the phrase, “to ensure the interest and security of the state”, in its long title. Hence, a data protection law that is sought to be legislated to protect individual privacy now has state security as one of its primary objectives.

The second point of concern emerges from the power of the central government to exempt departments from the application of the Data Protection Bill, 2021 as contained within Clause 35. This provision, first proposed by the Srikrishna committee, has witnessed considerable dilution. The exemption clause in the Data Protection Bill, 2018 was originally tethered to the conditions of legality, necessity and proportionality. This was diluted when the Data Protection Bill, 2019 was introduced in Parliament to satisfy the conditions of “necessity” and “expediency”, leading Justice Srikrishna to call this exemption a “dangerous trend”, potentially leading to an “Orwellian state”.

Instead of rectifying this provision, the Data Protection Bill, 2021 has cemented it. First, it adds a non-obstante clause, providing primacy to this provision over any other laws. Second, it stipulates that the procedure to be followed by the government agency must be just, fair, reasonable and proportionate. However, this change is only applicable to the “procedure” and not the substantive standards for the government’s invocation of exemption. To put it another way, the government does not need to establish that the exemption from the entire Data Protection Bill is necessary for, or proportionate to achieving its interest of national security or public order.

There is no doubt that data protection rights may not apply in totality when it comes to national security concerns. However, such exceptions, being in the nature of an “exception to the rule”, need to be limited and precise. For instance, under the United Kingdom’s Data Protection Act, 2018, the national security exemption does not extend to the entire Act; requires a certificate to be signed by the Minister of the Crown; and can be challenged by the affected person before a tribunal.

In contrast, in India, even the reasons for providing the exemption are not required to be tabled in Parliament. In fact, the order invoking the exemption is not a gazetted notification and will likely be exempt from RTI proceedings. Hence, the government can, without any oversight, exempt its own departments or ministries from the application of the Data Protection law in perpetuity.

In contrast, in India, even the reasons for providing the exemption are not required to be tabled in Parliament. In fact, the order invoking the exemption is not a gazetted notification and will likely be exempt from RTI proceedings. Hence, the government can, without any oversight, exempt its own departments or ministries from the application of the Data Protection law in perpetuity.

The third and final feature of the Data Protection Bill, 2021 concerns the Data Protection Authority, which is tasked with ensuring compliance with the law. The Justice B N Srikrishna panel had proposed an appointment committee consisting of judicial members, with the Chief Justice of India as chairperson, to choose members of the Data Protection Authority. This was watered down in 2019; the panel now included the cabinet secretary, law secretary and the IT secretary. This was heavily criticised for compromising the independence of the appointment process. Changes have been made in Clause 42(2) of the draft Data Protection Bill, 2021 by which the Attorney General, an expert, a director of an IIT, and a director of an IIM are included in the selection panel. This does not address the problem that the Centre appoints the nominees at its pleasure. Further, choice extends to the government in picking any one director from the multiple IITs and IIMs across India. In contrast, in the UK, under the Data Protection Act, the Information Commissioner is supposed to be appointed on the basis of “fair and open competition”, with candidates required to appear before a Parliamentary Select Committee prior to appointment.

Under Clause 87, the JPC has expanded the power of the central government, when it states, “the authority should be bound by the directions of the central government under all cases and not just on questions of policy”. This ties in with an unguided legislative allowance under Clause 92, which makes policies made by the central government override any protections or obligations under the Data Protection Bill, 2021. It is not without reason that Jairam Ramesh, a member of the JPC, has noted in his dissent that, “government agencies are treated as a separate privileged class whose operations and activities are always in the public interest and individual privacy considerations are secondary.”

The JPC report and the Data Protection Bill, 2021, by protecting the government instead of the personal data of Indian citizens, recalls the wry wit of Yes Minister: “The Official Secrets Act is not to protect secrets, it is to protect officials.”

This column first appeared in the print edition on December 20, 2021 under the title ‘A weak bulwark’. Gupta is the executive director of Internet Freedom Foundation; Bhandari is a practising lawyer in Delhi

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05