On Feelings, Morality, and Heretics

This week, I’ll be heading to Miami to participate in Hereticon, Founders Fund’s “conference for thoughtcrime”. As Solana and the rest of the team have been preparing for what is sure to be one of the most interesting conferences I’ve ever attended, I’ve been grappling with why I am so conflicted and uneasy about many of the topics that will be covered. I love debate and thrive in communities of people with whom I disagree with often, but some of this stuff just feels bad. Have I somehow convinced myself that my emotional responses are confirmatory indicators for moral, or even material/physical, truth? And if so, is that lazy thinking, or is it simply validation of some sort of nihilistic philosophical eventuality?

That could be a source of debate, but honestly, no. It’s definitely lazy. I’ll spare you all the pain of a 10,000 word treatise on truth vs relativism, but I do want to explore how this internal dialogue has led to me thinking differently, particularly in my role as an investor.

At its root, I believe much of this intellectual laziness is related to the seemingly unstoppable force of tribalism in our culture that has caused us to lose our ability to segregate emotional responses from logical ones. In many cases, our tribes have replaced authoritative morality with emotional response, and societal impact with self-satisfaction. This isn’t a partisan political statement. The left is no more or less guilty than the right.

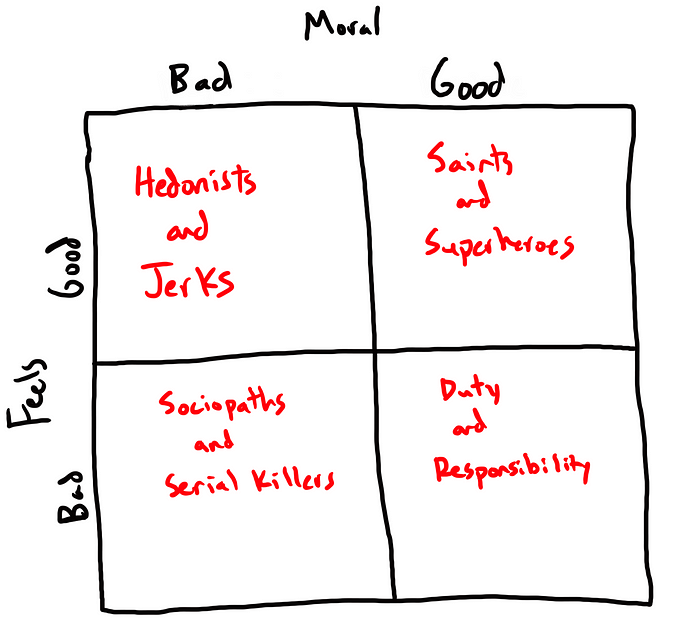

The most useful way that I’ve found to represent this phenomenon is with a…quad chart (cue sad trombone).

Before going quadrant by quadrant, it’s worth noting up front that you may find yourself disagreeing (maybe even strongly) with my placement of some of the ideas/categories. That’s ok! I’m making moral judgments here for the sake of clarity and argument, not because I’m claiming to be the ultimate arbiter of moral truth. But if you find yourself disagreeing with most or all of the placements (particularly in the top left and bottom right quadrants), then this may be a good indication that you are trapped inside the glass case of emotion.

Moral Good / Feels Good (Saints and Superheroes)

Volunteering/Charity

Social Justice Activism

Environmentalism

Improving Educational Outcomes

Caring for our Families/Elders

Most ideas/categories in this quadrant are worth working on. In fact, some may even be imperative for every decent person to contribute to. The problem with these ideas isn’t that they are bad (they generally aren’t), it’s that they tend to be over-represented and celebrated in a way that consumes energy and draws society away from the more complex and challenging categories with higher beta to meaningfully advance humanity.

As a result (and this is something we talk about a lot at Founders Fund), companies operating in this quadrant tend to be massively over-competed because of warm fuzzy peer validation. Or, if we’re talking about government organizations, this generally manifests as a stifling do-gooder bureaucracy that is more obsessed with procedural fairness than they are with solving problems. No bueno.

Moral Bad / Feels Bad (Sociopaths and Serial Killers)

Murder

Child Abuse

Fraud

Crony Capitalism

Pretty straightforward. The intellectual challenge here is being honest with yourself about whether or not the thing you are chasing unintentionally falls into this quadrant. Is there an indirect secondary effect that has significant risk of causing a horrifying moral negative? Does something that starts with good intentions end up drifting into fraud due to a desire for self-preservation (Theranos, Juicero, a s*&tcoin, etc)? Does massively scaled use of the product you are building increase rates of bullying or worse outcomes, like teenage suicide?

Centerpoint: Moral Neutral / Feels Neutral

Sadly, a huge percentage of all human intellectual capacity is wasted just turning the crank. You know who you are, b2b saas.

Moral Bad / Feels Good (Hedonists and Jerks)

Pornography

Religious Extremism

Astrology and other forms of Spiritual Esotericism

Drug Liberalization

Extreme Patriotism / Nationalism (some interesting thoughts on this here)

Gambling

Pervasive Social Media

This is where things start getting a little sticky. Rather than being suggestive about where we should as a society be spending time, it is suggesting where we should not, based on what is effectively a moral judgment. I can sympathize with the rationalization many people make about why many of these should fall into other quadrants, but the indirect secondary effects of these categories tend to be wildly destructive of the human condition. There seems to be some recognition of this with even the most ardent supporters, but that recognition primarily manifests as a statement against “addiction”. To be clear, “everything in moderation” is good advice, but for some behaviors this can become too tricky of a tightrope to walk.

There is a great Bible verse that hits this head on:

“I have the right to do anything”, you say — but not everything is beneficial. “I have the right to do anything” — but not everything is constructive. No one should seek their own good, but the good of others.”

1 Corinthians 10:23–24 (NIV)

Where there is a rejection of any sort of authority/truth, we all have a tendency to worship the corporeal, and that tends to get drawn out with big hits of dopamine.

Moral Good / Feels Bad (Duty and Responsibility)

Nuclear Power

Conservatorship

Disciplining Children

Better Pathways for Scaled Legal Immigration

Controlled Burns

Autonomous Weapons (see additional thoughts here)

Pro-Natalism

GMOs

Life Extension

Mass Automation of Human Labor

Our seeming inability to give requisite attention to these categories is possibly the dumbest of all societal failure modes. The world is an incredibly complex system and for most of the ideas that fall in this quadrant, it’s necessary to spend time thinking about secondary effects in order to grok why these things matter and are worth working on.

Quite a few of the best ideas/companies we see at Founders Fund fall in this quadrant. These types of founders tend to be less mimetic, have deep conviction/passion for what they are working on (you’d have to in order to be ok with getting constantly attacked), and their companies are usually built around original ideas that serve as a competitive moat…at least until others “catch up” to them being onto something.

Frustratingly, there is also a difference here between ideas falling in this quadrant in the commercial space and those that fall outside. If you are right in the market, you probably win eventually. If you are right in the arena of ideas, there is no such guarantee. You might well die unappreciated and scorned. There is a clear incentive for Founders Fund to shun the haters and invest in great founders in this quadrant. But there is no such selfish incentive to hear out, fund, or showcase outsiders in the arena of ideas. In fact, oftentimes incentive structures would call for avoiding that entirely. This is bad for humanity.

None of us are immune to these emotional biases. I’ll admit that there are several moral good / feels bad companies that I have debated strongly against in my role at Founders Fund, based upon the way they made me feel. This is a challenge for each of us to grapple with. Are we emotionally opposed to an idea because it doesn’t align with our own tribe’s narrative? Can we approach every response of intestinal disgust with an air of civility, curiosity, and thoughtfulness, never presupposing that we own the monopoly on truth or the right to impose our emotional response on others as a moral retort?

Many of you reading this are likely aware of my partner Peter Thiel’s favorite interview question: What important truth do very few people agree with you on? I’ve been asking this question in every interview I’ve conducted for more than a decade now, and have been keeping a record of every answer in the hope that some interesting and unique ideas worth remembering would come out of it. Sadly, the most interesting takeaway that has emerged is this: Just over 40% of the hundreds of people I’ve interviewed gave the same answer — that they believe people are inherently good. This is a quintessential “Saints and Superheroes” answer.

Peter describes this phenomenon in his book, Zero to One:

“This question sounds easy because it’s straightforward. Actually, it’s very hard to answer. It’s intellectually difficult because the knowledge that everyone is taught in school is by definition agreed upon. And it’s psychologically difficult because anyone trying to answer must say something she knows to be unpopular. Brilliant thinking is rare, but courage is in even shorter supply than genius.”

As Solana wrote in his original Hereticon blog post, “Every great thinker, every great scientist, every great founder of every great company in history has been, in some dimension, a heretic. Heretics have discovered new knowledge. Heretics have seen possibility before us, and portentous signs of danger. But our heretics are also themselves, in persecution, a sign of danger. The potential of the human race is predicated on our ability to learn new things, and to grow. As such, growth is impossible without dissent. A world without heretics is a world in decline, and in a declining civilization everything we value, from science and technology to prosperity and freedom, is in jeopardy.”

Bring it on, Hereticon.

Thanks to my friends Ben Chelf, Jeff Huber, Jeff LaBarge, Ben Pilgreen, Brian Schimpf, Babak Siavoshy, and Sam Wolfe for serving as a sounding board as I’ve worked through this.