Jumarts: Horse-cows and donkey-cows

Perissodactyla × Artiodactyla

This page was a draft for a chapter of my now-finished book on distant hybrids, available here >>

Today many biologists would reject the very possibility of strange mixtures like ox-horses. But in former times, claims by scholars of the existence of such hybrids were legion. Indeed, many of these now-repudiated authorities asserted that they themselves had seen such creatures. And the video above, of a living animal with a cow’s head but horselike hindquarters and tail, lends credence to their claims, in that it seems to confirm that horse-cow hybrids actually can be produced—though they may be rare and underreported—as do the numerous reports, images and videos cited below.

An explanation often given for such animals is that they are simply deformed hinnies, that is, the mutated offspring of a stallion and a she-ass. However, this idea does not account for the fact that some of these animals exhibit characteristics that are clearly bovine, such as horns and cloven hooves. Mutations often cause deformities, but they do not reproduce complex traits otherwise found only in distantly related taxa. The creature shown in the video linked to this page looks mostly like a cow, and when it lifts its feet in the video, it can be seen (at least in the YouTube original) that its hooves are cloven. And yet its hindquarters and, especially, its tail seem to connect it with a horse. Moreover, in many of the reported cases the mother was allegedly a cow, which certainly would preclude any possibility of the animal in question being a hinny. Here, then, another possibility is explored, i.e., that these animals might be rare or underreported hybrids.

Animals of this sort are known by various names (see Appendix 1), but perhaps the most common is jumart. This word has been used in English since the eighteenth century, as evidenced by its presence in Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language, defined as “The mixture of a bull and a mare.” Even earlier, it appears in the fifth edition of Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Locke 1706, p. 384). The word jumart appeared earlier in French, perhaps as a derivative of the similar French word jument, meaning “mare,” which in turn is related to Latin iumentum, “mule” or “beast of burden” (again, see Appendix 1).

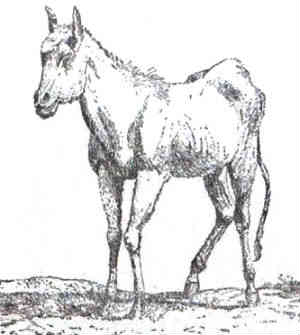

The earliest reports about such animals date back to ancient times. A famous example is Alexander the Great’s steed Bucephalus, whose name literally meant, “ox-headed” (see image right). Many classical authors seem to have taken it for granted that Bucephalus had the body of a horse but the head of a bull. Thus, Arrian (Anabasis, V, 18) writes that “The mark by which he was said to have been particularly distinguished, was a head like an ox, from whence he received his name Bucephalus.” As portrayed on ancient coins (e.g., at right) contemporary with the life of the animal, Bucephalus did have horns like a bull. Chares of Mytilene, an historian who attended Alexander’s court, wrote that Alexander’s father Phillip paid 13 talents for the animal, an equivalent of 312,000 sesterces in Roman money (see Gellius, Attic Nights, V, 2). This would amount to something like a million dollars in modern money. So cow-horse hybrid or not, Bucephalus must have been a very special animal.

It is well known that horses and donkeys do occasionally mate with cattle (e.g., see videos below). Such mixed matings are fairly common events on ranches and other places where these animals are likely to come into regular contact.

Indeed, from very early times, bovids have been known to mate with equids, as shown by the fact that ancient Akkadian cuneiform texts mention pairings between ox and ass, and between ox and horse (Freedman 2017, pp. 13, 20, 22). And a biblical injunction (Deuteronomy, 22:9-10) indicates the Israelites were concerned to prevent the production of donkey-cows: “Thou shalt not sow thy vineyard with divers seeds: lest the fruit of thy seed which thou has sown, and the fruit of thy vineyard, be defiled. Thou shalt not plow with an ox and an ass yoked together.” Writing in the first century A.D., the Jewish scholar Philo Judaeus (The Special Laws, III, 8:46) recorded the fact that it was forbidden to allow cattle to cross with horses:

But the more interesting fact is the mountain of evidence, already alluded to, indicating that jumarts actually exist. An attempt is made here to collect into one place any and all evidence available for this cross. The most obvious remaining obstacle to the full acceptance of their existence is the lack of any DNA study investigating a putative equid-bovid hybrid (though specimens are available in known locations, none seem to have been tested).

Gerolamo Cardano

Gerolamo Cardano Conrad Gessner

Conrad Gessner

Early reports. During the course of a search of the literature, the earliest scientific reference to jumarts encountered was in the writings of the Italian polymath Gerolamo Cardano (Contradicentium medicorum, 1548, Lugduni, pp. 444 & 448), who used these creatures as an example within the context of an argument he was making with regard to the hereditary content of semen. The fact that Cardano merely mentioned characteristics of this type of hybrid, without referring to an actual animal, suggests he was aware of some still earlier, as yet unidentified, primary report(s). The first edition of Contradicentium was printed at Venice in 1545.

Cardano was soon followed by Conrad Gessner, who, in his Historia Animalium (Liber I, De Quadrupedibus viviparis, 1551, p. 19), writes, “I hear occasionally of a peculiar sort of mule produced in France in the vicinity of Grenoble, which is born of a she-ass and a bull, and which, in French, are called jumarts” (translated by E. McCarthy). In the same place, he mentions a cow-horse hybrid, saying that he has “learned from credible witnesses that in the Swiss Alps above Chur, in the village of Splügen, a foal was born from a mare served by a bull” (translated by E. McCarthy).

Gessner, who was Swiss himself, was a professor at the Carolinum, the precursor of the University of Zürich. Elsewhere in the same publication (Gessner 1551, p. 106) he refers again to the strange birth at Splügen: “Here [in Zürich], we have heard the testimony of trustworthy men that they themselves saw a foal at Splügen in Rhaetia [i.e., in what is now eastern Switzerland] that was produced from a mating between a mare and a bull” (translated by E. McCarthy). One source of this information was likely the physician Jakob Ruf (1505-1558), who, according to his German Wikipedia biography, lived as a young man in a cloister at Chur up to the time of the Reformation in 1526, but later lived in Zurich, where he became the leading surgeon of the city. In his De conceptu, et generatione hominis, he mentions this same birth (Ruf 1587, p. 48), and gives a brief description: “For in Switzerland, a horse served by a bull gave birth, at the expected time, to a foal with the hooves of a horse, but otherwise, in shape, hair and tail, like a cow” (translated by E. McCarthy).

Julius Caesar Scaliger

Julius Caesar Scaliger

Julius Caesar Scaliger (1484-1558), a scholar and physician of the same era, called a hybrid of this type a “hinnulus.” He said (Scaliger 1612, p. 650; see also p. 349) it

The Gabali were native to the southwestern region of France known as Aquitaine, the Arverni, to the Auvergne, which lies near the center of France. Scaliger himself lived in Aquitaine, at Agen.

Likewise, Giambattista della Porta (1658, ch. 9, p. 39), the Italian scholar, polymath and playwright, avers that “I myself saw at Ferraria [i.e., Ferrara] certain beasts in the shape of a Mule, but they had a Bull’s head, and two great knobs in the stead of horns.”

Paul Zacchias (1584-1659), personal physician to popes Innocent X and Alexander VII, long resided at Rome. In his best known publication Quaestiones medico-legales (1651, p. 504), he winds up a section on hybrids by describing a jumart, which he claimed was for many years in the possession of Cardinal Borghesi: “And finally, I will say a bit,” he writes, “about a jumart, a hybrid born of a bull and a mare. He had a face like a cow, but in other respects was rather like a mule, except that he had the shanks of a cow, though the hooves

Paul Zacchias

Paul Zacchias John Locke

John Locke

The Franciscan missionary Girolamo Merolla da Sorrento (1726, p. 3) described jumarts he saw used as beasts of burden at Alghero in Sardinia in 1682 and mentioned that he had heard from “certain Portuguese gentlemen” that such beasts were also bred in the Cape Verde Islands. And the renowned philosopher John Locke, too, in a journal he kept during his travels in France, claimed to have seen a jumart:

And in the eighteenth century, Patrick Blair (1720, II, p. 310), a Scottish surgeon and a Fellow of the Royal Society, informs his readers that from

Thomas Shaw

Thomas Shaw F.-A. de Garsault

F.-A. de Garsault

And during his relation of the various animals he had seen during his time in northern Africa, the English cleric and traveler Thomas Shaw (1738, p. 239) described a jackass-cow hybrid, known in Arabic, he said, as a “kumrah.”

Shaw’s kumrah was cited in the writings of many subsequent authors who discussed jumarts, for example, by Réaumur (1751, vol. 2, p. 373), who mentioned his plans to dissect a jumart, and by Buffon (quoted below), who expressed doubts as to whether jumarts actually exist.

In his book Le Nouveau Parfait Marechal (1787, pp. 82-83), first published in Paris in 1741, horse expert François-Alexandre de Garsault (1693-1778), the King’s master of horse (“Capitaine des Haras du Roy”), gave the following account of jumarts and mules:

Mules are much more common than jumarts, as might be expected given that they are far more useful, especially in warfare. From the ass, they receive their sturdy hooves, sure footing and good health. These animals have strong backs and can carry far more weight than a horse. Some are good riding animals, but this is rare…[more information about mules omitted here].

A jumart is a small animal, a little larger than a donkey, but extremely strong. Its head rather resembles that of a bull, having a broad forehead and large muzzle, so much so that when one looks from the front, it seems almost like a bull without horns. Jumarts are common in the [mountainous] province of Dauphiné, where they are used as pack animals.

To produce a mule, the breeder arouses a jackass with a jennet and then substitutes a mare in heat. Likewise, to breed a jumart, he excites a bull with a cow, or a jackass with a jennet, and then introduces the substitution. Jumarts produced by bulls breeding with mares or jennets differ from those produced by jackasses mating with a cows, in that the latter lack incisors in their upper jaws.‡ [Translated by E. McCarthy. Original French.]

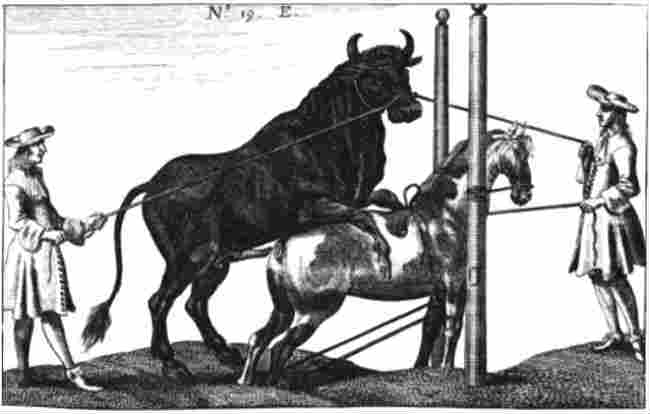

Mating a bull with a mare (Adlersflügel 1703).

Mating a bull with a mare (Adlersflügel 1703).

Indeed, eighteenth-century books on horse breeding gave explicit instructions on how to breed jumarts. At right is shown an illustration from the 1703 edition of Georg Simon Winter von Adlersflügel’s Stuterey (1703), a manual on horse breeding. Adlersflügel was a master equestrian and the author of numerous books on equine medicine. In connection with this illustration, he gave (1703, pp. 128 & 130) the following instructions on how to get a bull to cover a mare (which might be of use to modern experimenters with this cross):

Hindquarters of a horse and those of a cow.

Hindquarters of a horse and those of a cow.

The existence of such detailed instructions for producing horse-cow hybrids raises the question of why an expert on horse breeding should provide them, if no hybrids ever resulted from such matings. In breeding ordinary mules, mares are often made to stand in a hole in just the same way, so that short-legged jackasses can reach them.

However, a correspondent of Suchetet (1890, p. 19) stated that farmers rarely produced jumarts on purpose because (1) relatively few couplings resulted in a hybrid, and (2) they feared the hybrid would be cloven-hoofed, as sometimes happened, in which case it would not be sufficiently useful as a beast of burden and have to be destroyed at birth. For this reason, he said, most jumarts were born of fortuitous matings.

In late eighteenth-century France, belief in this equid-bovid hybrid seems to have been extremely widespread. For example, after the French Revolution the new official calendar renamed the months, and gave names taken from nature to each individual day of the year. The name of the 15th day of the new month of Messidor was Jumart. A French encyclopedia (Cours d’études encyclopédiques ou nouvelle encyclopédie élémentaire, vol. 6, p. 40), published during the revolutionary era, lists the beasts of burden as follows: “the horse, the ox, the ass, the mule, and the jumart.” Voltaire, widely considered one of France’s greatest Enlightenment writers, accepted the reality of cow-horse hybrids as much as he did that of mules (see Voltaire 1792, p. 200).

Zirkle (1935, p. 34) says this cross “was cited as an authentic instance of hybridization for well over two hundred years.” He also notes that many of the descriptions “seem to be independent eyewitness accounts from several different countries, and no one ever seems to have doubted the creature’s existence.” This last statement, however, is not entirely accurate; many people, for example Buffon (1749-1804, vol. 14, p. 398), did express doubts, which is not surprising, given that cattle are artiodactyls (“even-toed ungulates”) while horses and asses are perissodactyls (“solid-hoofed ungulates”), that is, they belong to two separate mammalian orders. In other words, if one judges their degree of relationship on the basis of their taxonomic classification, a horse and a cow are as distantly related as are, say, a cat and a rabbit, a dog and a human being, or a pig and a weasel. Buffon (1771, p. 18) stated his argument thus:

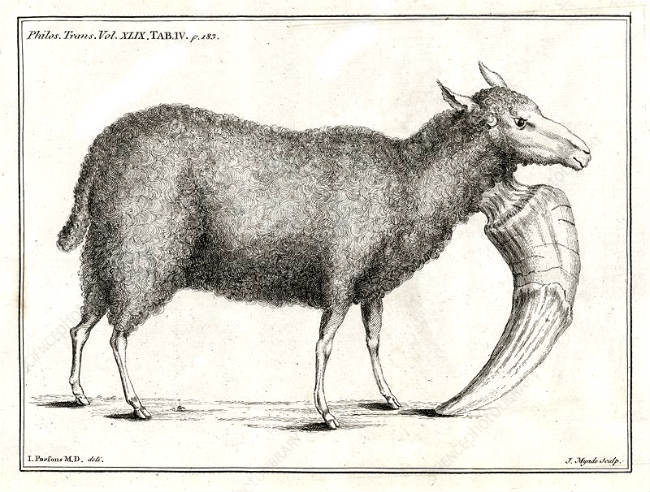

A jumart (Buc’hoz 1782-1788).

A jumart (Buc’hoz 1782-1788).

But Buffon is just one witness, who, by his own admission, examined only two animals. Moreover, in a passage quoted below, he himself later described a bull that voluntarily covered a mare “three or four times a day,” which clearly indicates that these animals do sometimes “unite with pleasure.”

In that same era, many other witnesses reported cow-horse hybrids and considered them real, especially in France. For example, in his Histoire générale des animaux (1782-1788). the French naturalist Pierre-Joseph Buc’hoz (1731-1807) included a picture of a jumart, alongside those of oxen, horses, mules, donkeys, and the various other common domestic animals. His illustration, shown at right, was accompanied by this caption:

Baretti

Baretti

An eyewitness from the same era was Giuseppe Marc’Antonio Baretti (1719-1789). Baretti was an Italian literary critic, translator and writer. In his book An Account of the Manners and Customs of Italy (London, 1769, vol. 2, pp. 281-285), he says, “As for the carrying of burthens, we [i.e., the Italians] make use of mules, and of another animal called Gimerro [In a footnote here Baretti says, “Gimerro in English is Jumart.”], expecially throughout the mountains where horses would soon perish. Of mules we have great droves continually carrying merchandises, particularly over those parts of the Apennine that answer to the port of Leghorn; those of the Alps that lie between Italy and Savoy, Switzerland, and Tyrol; and those which geographers call the Ligurian Alps. Some of the muleteers of the Apennine draw even carts

with mules; but those of the Alps never do, or at least I never saw any that did. Perhaps the greater height of the Alps and their unconquerable ruggedness causes the want of this convenience.

It will not be improper to say something of the gimerros, as I find that no travel writer, of the many I have read, has ever mentioned them, and that they are but little known even to those of my English friends who delight in various and extensive reading. A gimerro is an animal born of a horse and a cow; or of a bull and a mare; or of an ass and a cow. The first two sorts are generally as large as the largest mules, and the third somewhat smaller. I have been told by some muleteers in several parts, that the sires of these animals are first shewn a female of their species just before the leap; then led forcibly to one of the species intended, which is kept at hand. The Alpine peasants assure us, that they might get a fourth kind between a bull and a female ass, but that they ordinarily prove sorry things. Of the two first sorts I have seen hundreds, especially at Demont, a fortress in the Alps (about ten miles above the town of Cuneo), that was much talked of during the last war between the French and the Piedmontese. There many of these gimerros were used, chiefly in carrying stones and sand up to the fortress that was then a-building on a high rocky hill. Of the third species, I rode upon one from Savona to Acqui, so late as the year 1765. [Here, Baretti inserts the following footnote: “Savona is a town on the Ligurian coast, belonging to the Genoese, and Acqui is the capital of Upper Monferrat, belonging to the king of Sardinia.”] It was a sluggish beast, scarcely sensible of the bit and whip; but wonderfully sure-footed; and riding that way in January, as I did, in a most rugged by-road, the whole country round covered in a deep snow; many a mile in a narrow path, often on the brink of a precipice, and all the north sides of the frequent cliffs (over which I was to go) perfectly hidden under the hardest ice; going such a way, I say, I had really need of such a beast, that was very careful not to fall.

The gimerros resemble the mules so much, that, if you are not told, you will scarcely ever think of the difference, which chiefly consists in the ears, not so long as those of the mules; in the parts of the head about the nostrils and mouth, which in the gimerros are generally rounder than in the mules; and in the middle of the back, which is sharper in the mules than in the gimerros. Those between a bull and a mare have likewise a fiercer aspect than the other two species; and the species of that on which I went that journey, have upper fore-teeth remarkably more forward than their under; yet they feed very well.

Indeed, eyewitnesses attesting the existence of such animals are innumerable. The English poet and cleric Thomas Sedgwick Whalley (1746-1828) wrote about a journey he once took on a jumart (see Appendix 3). The Flemish-Dutch soldier and author Bernard Rottiers (1771-1857) gives an account telling of jumarts he encountered while stationed in Russia (see Appendix 4). And his contemporary, Christophe de Villeneuve-Bargemon (1771-1829), a French official, described how he saw many jumarts during his sojourn in the Vallée de Barcelonnette (today’s Vallée de l’Ubaye) in the French Alps (Voyage dans la vallée de Barcelonnette, 1815, p. 89). In one of his letters written from that valley, he says that

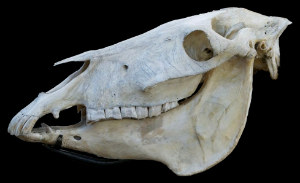

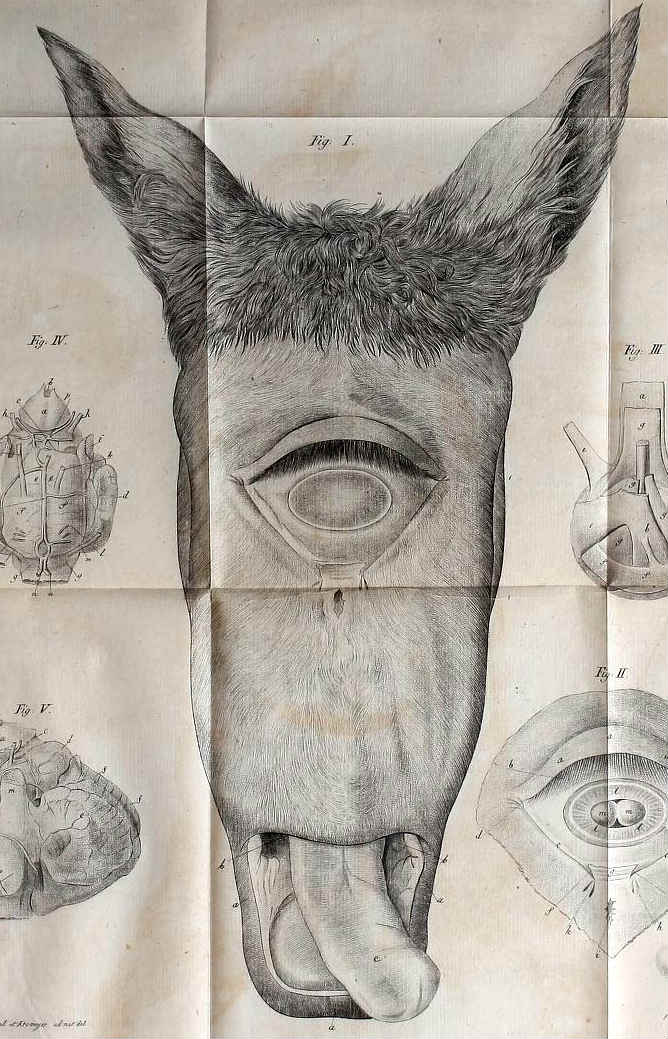

A jumart skull (Image: Musée Fragonard d’Alfort).

A jumart skull (Image: Musée Fragonard d’Alfort). The structure of the skull of an ordinary mule, shown here, is markedly different from that of the Alfort specimen. Hinny skulls do not differ in any consistent way from those of mules.

The structure of the skull of an ordinary mule, shown here, is markedly different from that of the Alfort specimen. Hinny skulls do not differ in any consistent way from those of mules.

Bourgelat’s specimen. So then, are these animals really equid-bovid hybrids or merely hinnies as Buffon and other naysayers have suggested? A key to resolving this issue will no doubt prove to be the fact that specimens are available, at least two at Kitale Nature Conservancy (the living animals shown in the videos above), and a skull in a Paris museum (shown at right). Since these three specimens would presumably all be F₁ hybrids, it would be easy to test them with molecular genetic techniques. And given that there are at least two present in a single facility, at Kigale, they are probably not so rare that a diligent search would fail to locate others.

I was first led to the Paris specimen after reading Ackermann (1898, p. 74), who stated that there was a skeleton of a jumart in France in the collection of the Musée Fragonard d’Alfort, an anatomical museum associated with the French National College of Veterinary Medicine at Alfort (Écoles nationales vétérinaires d’Alfort), located today in Maison-Alfort outside Paris. Ackermann’s assertion prompted me to explore the museum’s website, which did indeed turn out to have a page discussing jumarts, and which includes a photograph of a skull (see figure above at right and high-resolution image below). The following is a translation of that page (accessed Apr. 20, 2010, but the page has since been deleted. A copy of the original French is preserved in Appendix 2): “Monstrosities were little studied in the early years of the Écoles Vétérinaire, but there is one exception that stirred a longstanding controversy: the jumart (or jumard or joumart). This animal, said to be the hybrid of a bovid and an equid,

An enlargeable image of the Alfort skull (high-resolution image). Given that the label, visible beneath the skull in the (enlarged) photograph, reads “Tête de jumard. Auteur: C. Bourgelat” (“Head of a jumart. Collector: C. Bourgelat”), this specimen must have been obtained from one of the animals Bourgelat claimed to have had in his possession during the years he served as director and inspector general of the French National College of Veterinary Medicine at Alfort. Twenty-six years after Bourgelat’s demise, Rudolphi (Rudolphi 1805, pp. 46) described the complete head and neck of a jumart in the Alfort collection. This head and neck is apparently the source of the jumart skull pictured here, because Goubaux (1888, p. 479, footnote), writing toward the end of the nineteenth century, states that although this head and neck were not recorded in the museum’s catalog, he had himself seen this piece, and that it had been boiled because it was in poor condition and only the osseous portion of the head preserved.

An enlargeable image of the Alfort skull (high-resolution image). Given that the label, visible beneath the skull in the (enlarged) photograph, reads “Tête de jumard. Auteur: C. Bourgelat” (“Head of a jumart. Collector: C. Bourgelat”), this specimen must have been obtained from one of the animals Bourgelat claimed to have had in his possession during the years he served as director and inspector general of the French National College of Veterinary Medicine at Alfort. Twenty-six years after Bourgelat’s demise, Rudolphi (Rudolphi 1805, pp. 46) described the complete head and neck of a jumart in the Alfort collection. This head and neck is apparently the source of the jumart skull pictured here, because Goubaux (1888, p. 479, footnote), writing toward the end of the nineteenth century, states that although this head and neck were not recorded in the museum’s catalog, he had himself seen this piece, and that it had been boiled because it was in poor condition and only the osseous portion of the head preserved.

Horse skull

Horse skull Donkey skull

Donkey skull

Cow skull

Cow skullThe jumart skull mentioned in this translated text is pictured on the same webpage (an enlargeable photo of the same skull is shown above). If this skull, is in fact that of a jumart, then clearly equid-bovid hybrids are possible, however imaginary they might be imagined to be. The skulls of mythical animals do not end up in museum collections. So either this type of hybrid has been produced, or the skull pictured is a fake or that of some other creature. Note, however, that this skull, which the label in the Musée Fragonard’s exhibit actually describes as a jumart’s, differs markedly from that of a cow, horse or ass. Nor is it at all similar to that of either an ordinary mule (mare × jackass) or a hinny (stallion × jennet). The picture of a mule skull shown here suffices to represent also, the skull of a hinny since Allen and Short (1997, p. 385) say, “We still lack conclusive proof as to whether there is any consistent phenotypic difference between mules and hinnies.” So if it is not a jumart, what is it? And what are the animals shown in the videos (see above)?

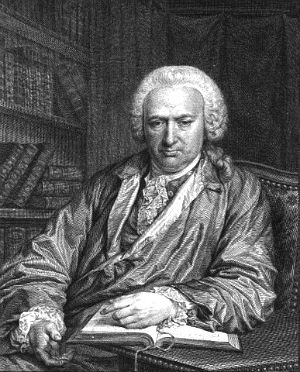

Bourgelat’s jumarts. The French college of veterinary medicine is one of the world’s oldest. Its main branch at Alfort opened in 1766, and its museum, the Musée Fragonard, located at that branch, opened in the same year. The founder of both (as well as the original branch of the college at Lyon, which first opened its doors on January 1, 1762), the veterinary surgeon Claude Bourgelat (1712-1779), began the museum’s collection. He was a member of both the French and Prussian academies of sciences. Many veterinary colleges in other countries were founded by his students, who took the French college as their model.

In his Oeuvres d’histoire naturelle et de philosophie, an encyclopedia of natural history, the Swiss scientist Charles Bonnet (1779, vol. 6, pp. 349-352) described correspondence he exchanged with Bourgelat on the subject of jumarts. “Confronted with authorities of conflicting opinion, I greatly desired to be able to make up my mind on the interesting question of the existence of jumarts. In a magazine, I had seen the description of a jumart that M. Bourgelat, Inspector General of the Écoles Vétérinaires de France, had caused to be dissected under his direction at the Lyon branch of the school, but dared not trust the report of a journalist. Having to publish

Claude Bourgelat

Claude Bourgelat Charles Bonnet

Charles Bonnet

Elsewhere, Bourgelat stated that he himself produced a jumart by mating a stallion with a cow. The following is an English translation of Bourgelat’s claim, as quoted by Bonnet (1779, p. 547).

Bourgelat’s account is important because it cannot be explained by the argument that alleged jumarts are all hinnies (i.e., offspring of a stallion mated with a jennet). Those who have argued that jumarts are impossible have often used this argument to undermine the validity of reports about jumarts. But the offspring of a cow would, of a certainty, have a cattle component in its hereditary composition, and therefore could not possibly be an ordinary hinny, even if it happened to resemble one.

In the present context, it also appears significant that (1) descriptions of jumarts regularly mention that the upper jaw is much shorter than the lower (the usual distance mentioned is “an inch and a half”), and (2) that in the picture shown above, of what the museum website describes as the “skull of a jumart,” (“tête osseuse de jumard”) that the incisors in the upper jaw do, in fact, fall far short of those in the lower. This is not the case in a horse or an ass, and a cow does not have upper incisors. There seems to be no known animal with a similar mismatching of the incisors, nor one with a tooth and skull configuration like that seen in this putative jumart. In an old description of these animals, Leger (1669, p. 7) says this mismatch generally prevented the jumarts he saw from grazing, except in fields with long grass, where they could crop by pulling it off with their tongues. Similarly, Paul Zacchias (quoted above) mentions that an old jumart belonging to Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577-1633) had to be put down because it could not eat grass or hard food.

There is also the fact that the Alfort specimen has an obvious knob or prominence over each eye, another feature mentioned in many descriptions of jumarts. (These knobs are better visible in the smaller of the two images of the specimen shown above, as the higher-resolution image was taken from an angle that makes it harder to see them.)

In the article quoted above, Bonnet (1779, vol. 6, pp. 351-352) includes an excerpt from Bourgelat’s letter, a section describing the anatomy of a female jumart:

With its enveloping soft tissue removed, one finds the cranium much more rounded than in a horse. The frontal bone is larger; the nasal bones more depressed in their upper part; the orifices of the nasal cavities, and the cavities themselves, much narrower; the orbital opening, round, whereas in the horse it is oval; the palette, much longer and more concave; the upper jaw an inch and a half shorter than the lower, the former being, as in cattle, at least two inches wider than the latter. Each jaw contained twelve molars, six on each side; those of the upper jaw describe an arc posteriorly. … the region corresponding to the space between the canines and first molar was flattened relative to the horse, and one and a half inches in length, and convex, whereas in the horse it is concave.

This jumart had neither canines nor wolf teeth. The incisors, which are eight in number in the lower jaw of a cow, here numbered just six in each jaw. They were an inch and a half long. They were not vertical, but inclined forward so that the upper jaw did not bear on the lower jaw except at the very tip of the left first incisor.

The tongue did not differ from that of a cow. And its papillas or buds were as easily distinguished as in that animal.

The throat was much much larger in diameter than than in a horse. [irrelevant comments omitted here] The stomach was single and shaped exactly as in the horse, but it was much larger.

The spleen was of the same shape and of the same consistency as that of a cow.

The uninary bladder at its greatest dilation had a diameter of no more than three inches.

The uterus was exactly like that of a mare or a she-ass. [description of uterus omitted] The ovaries were the size of a fava bean, soft and flaccid. [Hybrids often have small, soft gonads]

It may also be mentioned that there was no gall bladder [A gall bladder is present in cattle, but not in horses.] and no difference in the structure of the remaining visceral organs, which resembled those of a mare in all respects. The musculature was similar to that of a horse in all respects. M. Bourgelat ended his account with the following words: “Since that time we have opened and dissected several jumarts, both male and female, and I can assure you that all had a single stomach and no gall bladder.” [Translated by E. McCarthy. Original French.]

Albrecht von Haller

Albrecht von Haller Lazzaro Spallanzani

Lazzaro Spallanzani

According to the French zoologist and teratologist Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1860, vol. 3, p. 146), Bourgelat’s testimony also convinced the prominent naturalist Albrecht von Haller (1708-1777), a contemporary of Bourgelat who had at first denied the existence of jumarts, that they were in fact real. Geoffroy may be referring to an admission Haller made late in life in a letter to Charles Bonnet dated May 2, 1775 (See: The Correspondence between Albrecht von Haller and Charles Bonnet, ed. O. Sonntag, 1983, Bern, Hans Huber Publishers, p. 1163):

And the previous year Haller (1774, vol. 1, pp. 497-498) had spoken of jumarts in published work as if he deemed them real. Geoffroy (ibid) also says the Italian biologist Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729-1799) accepted their existence. Spallanzani was a Fellow of the Royal Society. Indeed, Spallanzani (1785, p. 219; see also p. 317), a contemporary of Buffon stated that the

Bonnet (1779, p. 547) said that he looked forward to further enlightenment from any new research by Bourgelat with regard to jumarts, but Bourgelat died that same year.

Johann Jacob Volkmann

Johann Jacob Volkmann

Other reports. During the same era, the German writer Johann Jacob Volkmann (1777, p. 240) reported that two living jumarts, a male and a female bred in Savoy, could be seen in the menagerie of the Landgrave of Cassel, a fact confirmed by horse experts Johann Gottfried Prizelius (1777, p. 165) and Georg Hartmann (1786, p. 376). And the diplomat Karl Heinrich von Gleichen (1733-1807) records an additional German case, also confirmed by Hartmann (ibid). Gleichen relates how in his youth, while working at “the great stables at Bayreuth, I quite often saw two [jumarts].…The ones I saw at Bayreuth were purchased at Arles in 1755 for more than a hundred pounds apiece.

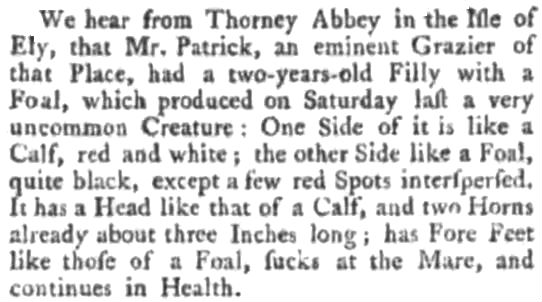

Jackson’s Oxford Journal (Jun. 18, 1768, p. 1, col. 3) had a report about a jumart born in Cambridgeshire, England. From the description given, the animal in question would have been a hybrid bilateral gynandromorph, a rare condition in which one side of a hybrid is similar to one of its parents, the other, like the other. Only a very few such cases have been reported. A screenshot of the report appears above, a transcript, below.

And the agronomist André Sarcey de Sutières (1788, p. 3), too, recorded an eyewitness description of a jumart: “I myself have owned three jumarts, all of whom have rendered me great service. The one I had the longest

He goes on to describe how useful jumarts are:

(Sarcey de Sutières’ rather lengthy discussion of jumarts can be read in its entirety in Appendix 5.)

Louis-Furcy Grognier (1773-1837), a member of the Academie Français and the French Society of Medicine, was a professor at the École nationale vétérinaire at Lyon, and, later, its director. Like many veterinarians of his era, Grognier affirmed that equid-bovid hybrids exist, though he considered them rare. Thus, he says (Grognier 1841, pp. 83-84; see also Grognier 1805, p. 188), “Enlightened individuals worthy of credence claim to have seen these animals [but] most naturalists deem them imaginary. However, whatever the differences may

In his article on mules in the Encyclopédie méthodique (Azyr 1821, X, p. 391), the French physician Jean-Joseph Brieude (1729-1812) concurred with Grognier’s view that hybrids of this type are rare. He had seen only two, he said, in his native Cantal, a little-populated department of France’s mountainous Auvergne region.

Given that these animals seem to be rare—if they exist at all—the attitude expressed by Grognier himself (1805, p. 194) seems reasonable enough:

In the same publication, Grognier (1805, pp. 194-195) mentions his friend and colleague, Claude-Julien Bredin (1776-1854), who also served (1815-1835) as Director of the French School of Veterinary Medicine at Lyon. Grognier writes that “while at Sospello in the Maritime Alps department where he [Bredin] was performing his duties as a veterinarian to the artillery, was shown an animal that was supposed to be the offspring of a bull and a she-ass. It was 3 feet 5 inches in height. Its body

The incisors of the lower jaw were properly placed but those of the upper jaw, displaced toward the rear: the first incisors were very large, but the second and third, excessively small; the eyes were extremely large, and the end of the nose, quite slender, as in an ass.

This bizarre animal was male and its sexual organs resembled those of an ass. [Translated by E. McCarthy. Original French.]

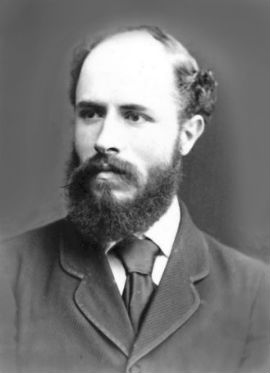

And there are other detailed firsthand reports by veterinarians about such hybrids. For example, the following, written by veterinary surgeon John William Gloag (1812-1886), appeared in the British journal The Veterinarian (1830, vol. 3, pp. 431-433).

The Peculiarities of a Cow and Horse

By Mr. J. W. Gloag, V.S.

A short time since I called upon Mr. J. Skilt, V.S., at Southwark Bridge, and he informed me that he had seen the skeleton of a very strange animal at the knacker’s; and wished me to go and examine it with him. I did so; and was much surprised and pleased once more to have an opportunity of surveying the monstrosity I have just been describing; and I am enabled to add the following particulars to my previous description of her:—The occipital and pterygoid processes are large, and the former very broad and projecting, and differing from the triangular-shaped process in the horse. There are no signs of horns. Just above the three anterior molars on each side is a large projection, similar to specimens of disease wherein the teeth have still remained in their sockets. The three first molars are perfect cow’s teeth. The ileum and pubis are laid nearly flat, as in the cow. The number of ribs and vertebrae are the same as in a horse. All the joints seem to be unusually large. The greatest peculiarity is, however, in the off fore foot; and I am obliged to be very concise in my account of it. Articulating with the lower head of the large metacarpal bone is another, altogether shorter and broader than the large pastern of the horse, and cleft nearly to its middle; and, articulating with each division, are the remaining small bones of the foot. There are two hoofs, separately joined, with a natural [separation] between them; but they have grown enormously since I saw the animal alive. The knacker informed be that he did not perceive any thing in the stomach different from that of the horse. Any gentleman who wishes for more information can examine this, and many other curious specimens, at Winkley’s Yard, in Fryer’s Street, Borough. The only history I could learn of the animal was, that the owner had purchased her from the breeder, who stated, that her dam, when very old, had been put out on Finchley Common with a bull; that no horse could have access to her; and that this very singular animal was probably the offspring of the mare and the bull.

Some biographical information on Gloag (taken from Smith, F. 1933. The Early History of Veterinary Literature and its British Development, vol. 4, pp. 39-40): “JOHN WILLIAM GLOAG (1812-1886), an army veterinarian of great ability, singularly attractive personality and high ideals. He was all that is implied in the phrase ‘a great gentleman.’ In 1858 he was elected a Vice-President of the R.C.V.S. [i.e., Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons] He was a careful and exact observer and furnished many papers to the Veterinarian.”

Blumenbach

Blumenbach Buffon

Buffon

Naturalists vs. veterinarians. Many naturalists, however, who were not veterinarians, did not believe that jumarts exist. This school of thought seems traceable in its origins primarily to the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840) and, in France, to the Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788).

Blumenbach was highly influential, especially among German naturalists. As science historian Peter Watson (The German Genius, 2010, p. 81) points out, “roughly half the German biologists during the early nineteenth century studied under him or were inspired by him.” And he, in his Handbuch der Naturgeschichte (1779, p. 112), which he wrote while he was still in his twenties, claimed that alleged jumarts were actually hinnies. The book was widely cited for decades (for more of Blumenbach’s arguments contra jumarts, see De generis humani varietate, 1781, pp. 15-16).

In an account much cited by subsequent writers arguing that jumarts do not exist, Buffon (Histoire Naturelle, 1829, vol. 16, pp. 392-393) told how matings between a horse and a cow had failed to produce a horse-cow hybrid: “On my family estate, in 1767 and subsequent years,

But not everyone agreed with Buffon and Blumenbach, and many veterinarians, who, unlike most naturalists, had daily contact with cattle and horses, continued to believe in equid-bovid hybrids long after Buffon’s demise. And reports of such animals continued to crop up. For example, the New York Daily Tribune (May 8, 1851, p. 6, col. 4) mentions “a young colt with hoofs split crosswise, and each part separate like that of a cow.” And the following brief notice about a horse-cow hybrid appeared in the Michigan newspaper True Northerner (Jan. 5, 1872, p. 3, col. 4): “The latest freak of nature is an animal at Council Bluffs [Iowa], which is half horse and half cow.”

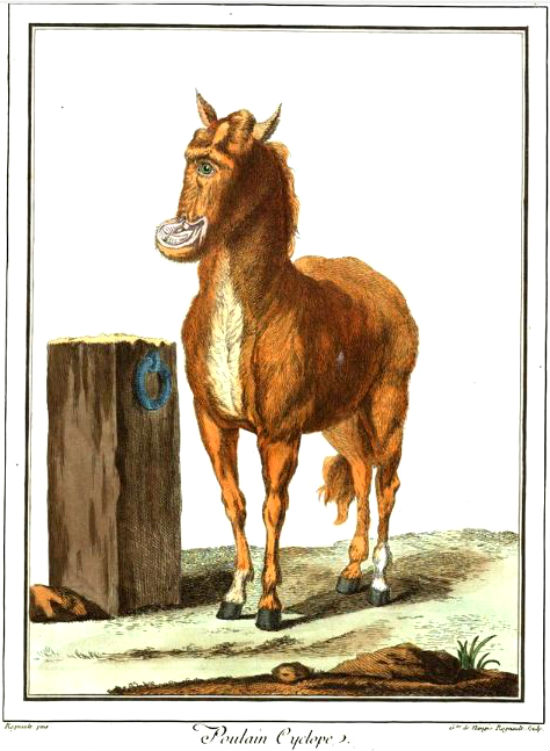

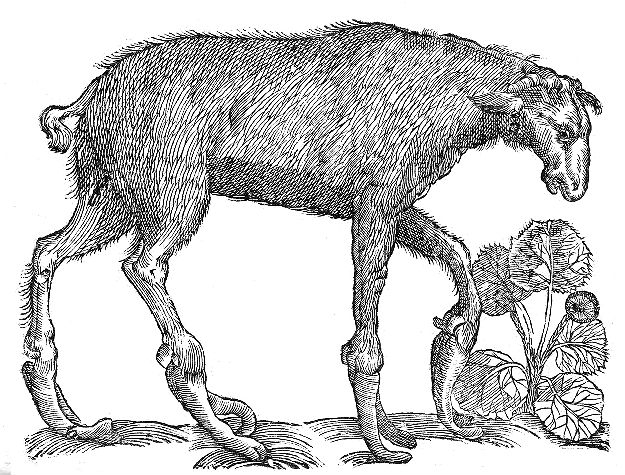

A cyclopean jumart?

A cyclopean jumart?(Moreau de la Sarthe, 1808)

Another cyclops in which the upper jaw was much shorter than the lower, the offspring of a mare (source: Ruben, 1824, tab. 1, fig. 1).

Another cyclops in which the upper jaw was much shorter than the lower, the offspring of a mare (source: Ruben, 1824, tab. 1, fig. 1).

A similar notice, but in this case reporting a cyclops, appeared in the Indianapolis, Indiana, Journal (Jul. 23, 1893, p. 16, col. 2):

The description of this last mentioned specimen is reminiscent of another cyclops birthed by a mare and pictured in an early nineteenth century compendium of anomalous births, Louis Jacques Moreau de la Sarthe’s Description des Principales Monstruosites dans L’Homme et dans les Animaux (1808, plate 3). This animal (see image at right) may perhaps be interpreted as a rather horse-like cyclopean jumart with an unusually short upper jaw. This individual survived much longer than the California cyclops (about four months). A rather similar cyclops, also with an upper jaw that was much shorter than its lower, was described by Meckel (1828, pp. 159-166). It, however, was birthed by a cow, not a mare. In general, cyclopean births seem to be more common in distant hybrid crosses, perhaps due to disruptions in development caused by the melding of highly disparate genomes.

During the nineteenth century the weight of scholarly opinion gradually shifted toward a rejection of the possibility of, not only jumarts, but also any other kind of hybrid between parents thought to be as distantly related as a bovid and an equid. Thus we find that in describing a jumart he saw while in Turkey, Henry Harcourt Hyde Clarke (1867, p. 500), a friend of Alfred Russel Wallace, felt the need to mention that the actuality of such animals was doubted by naturalists.

Indeed, it seems that for a time during the mid-nineteenth century opinion regarding the existence of jumarts differed between naturalists and veterinarians. At least one naturalist, the French palaeontologist and entomologist Paul Gervais (1855, p. 154), specifically stated this to be the case, “Naturalists,” he said, “have accepted the opinion of Buffon, but such is not the case with veterinarians, who are far from convinced” (translated by E. McCarthy). It seems that naturalists were more influenced by theoretical notions about what was possible with regard to hybrids, while veterinarians were swayed by what they had seen in their encounters with actual animals.

Gervais went on to explain why he himself did not believe in jumarts: “Unfortunately, these singular productions have either not been described with the care they deserve, or in those cases where they have been, they are easily recognized as a few monstrous individuals, just as one

But many of the reports that have already been cited cannot, as Gervais asserts, be satisfactorily explained “without supposing that some foreign fertilization has occurred.” When Gervais says “monstrous individuals,” he seems to be referring to what today would be called mutants or mutations. But it is unclear how a mutation would convert, say, the right forefoot of a horse into the cloven hoof of a cow, as in the animal described above by Gloag, and convert the hips and tail of that same animal into those of a cow, as Gloag also describes. The many ostensibly mixed traits of that animal can be more economically accounted for by supposing it was a hybrid between a cow and horse. For it to have been a simple mutant, it would have had to have undergone not one, but multiple independent mutations, which would all have just happened to be mutations that made it similar to a cow. Such an event seems unlikely.

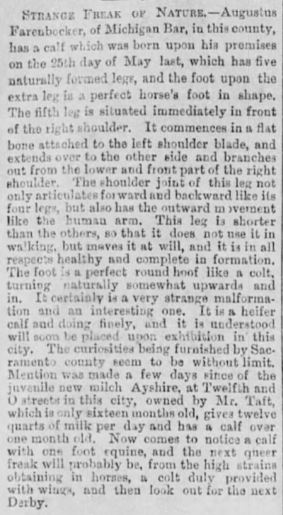

Above: A report about a calf with a fifth leg like that of a colt (Sacramento, California, Record-Union, Aug. 25, 1881, p. 3, col. 1; ||y5ofxbnr).

Above: A report about a calf with a fifth leg like that of a colt (Sacramento, California, Record-Union, Aug. 25, 1881, p. 3, col. 1; ||y5ofxbnr).

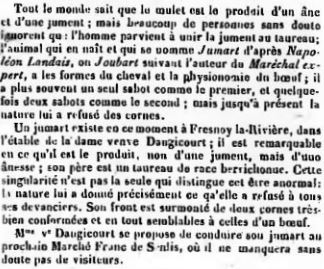

And in some cases the traits attributed to reported jumarts are incontestably bovine. An example is the following case, described in the French newspaper Journal de Senlis (Jul. 1, 1854, p. 1, col. 4), in which the animal reportedly had horns just like those of a cow. The owner of the animal in question was a resident of Fresnoy-la-Rivière, a village in northern France about 30 km west of the town of Senlis.

Screenshot of the original French-language news report translated at left.

Screenshot of the original French-language news report translated at left.

A jumart is now present at Fresnoy-la-Rivière in the stable of the widow Dangicourt. He is unusual in being the offspring, not of a mare, but of a jennet. His father is a Berrichonne bull. And this is not his only distinction. Nature has given him what she has refused all his predecessors. His forehead is adorned by two very well-formed horns, entirely similar to those of a cow.

Madame the widow Dangicourt plans to exhibit her jumart in the next Frankish Market at Senlis, where he will no doubt have no lack of viewers. [Translated by E. McCarthy. Original French]

Other reports about jumarts with horns are rare but do exist. Another such appeared in the Alexandria, Virginia, Gazette (Aug. 10, 1878, p. 2, col. 6). The report, which originated from the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, reads as follows:

The horns drop off every spring, about the 1st of May, and are succeeded by new ones of the same size. The horse is a bay mustang, about fourteen hands high, and rather poor in flesh at present. He is perfectly gentle, and will readily enter a house or other enclosure, and allow himself to be handled. Mr. John Grimsley, who knows something about a horse, examined his mouth yesterday, and pronounced him seven years old. He says the animal is the most wonderful thing in the equine line he ever saw, being a greater curiosity than Fremont’s Woolly Horse, or the hairless horse exhibited in the city some years ago.

And Gervais certainly has no basis for his claim that jumarts are never viable. As an entomologist, his personal experience with reports about such animals must have been limited. And the mere fact that some of the reported animals were inviable in no way implies that they all were. Indeed, in many hybrid crosses both viable and inviable offspring are produced (McCarthy 2006). And in more distant crosses, the percentage of inviable hybrids seems typically to be higher, all other things being equal. So one might expect there to be, along with the many viable horse-cows and donkey-cows that have been reported, a certain number that were inviable. And such reports are in fact on record.

For example, an inviable horse-cow is reported in an Australian newspaper, the Hamilton, Victoria, Spectator (Sep. 30, 1879, p. 2, col. 6):

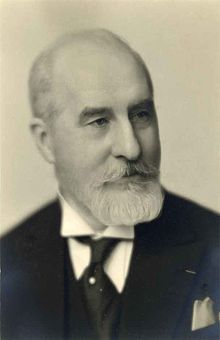

Suchetet

Suchetet

Suchetet. In 1890, André Suchetet (1849-1910) published an article in which he argued that jumarts are merely imaginary animals. An online biography describes him as a politician and “big landowner” (“gros propriétaire terrien”). From 1898 to 1910 he served as a député in the French National Assembly (the equivalent of a U.S. representative). Although Suchetet was a member of the Zoological Society of France, he seems never to have been affiliated with an academic institution, nor to have held a doctorate. He did, however, publish some scientific communications, including a much cited article (Suchetet 1890) dismissing the existence of jumarts.

In his paper, Suchetet cites many authors who had reported seeing or hearing about jumarts, or who merely expressed their opinion about the possible existence of jumarts, yea or nay. However, in his tone, and even in the title of his article (“La Fable des Jumarts”), Suchetet makes it clear from the outset that his own opinion was that jumarts do not exist, have never existed, and cannot exist. But why did he, and the various other naysayers he cites, reach such a conclusion? In particular, one wonders why he would have chosen to ignore the reports of so many eyewitnesses. He even dismisses one witness who he himself says (Suchetet 1890, p. 21) “had provided details that were sufficiently precise” (“a donné des détails assez précis”). It was the case of a farmer living at Sainte-Eulalie in the canton of Burzet, Ardèche, who when his stallion had refused to mount one of his mares, had replaced the stallion with a bull, who covered the mare. The mare conceived, according to the witness, though she was at no other time in the presence of a stallion, and, he said, she eventually produced a hybrid offspring (see Suchetet 1890, p. 19).

Suchetet’s decision—and that of others—to reject the very possibility of jumarts can be accounted for in various ways:

- Bias. Simple bias is one likely factor. Among religious people there is a widespread notion that by divine edict the various kinds of animals and plants are kept separate through an inability to hybridize. The notion is that this prevents “confusion of the species.” Anyone who believed this would obviously be more willing to believe that jumarts, specifically, are impossible. And even among the non-religious there is a prevalent belief that hybrids are somehow rare, unnatural and undesirable. Those who harbor such opinions are, again, more willing to accept unproven claims that jumarts simply cannot be, because to accept that they did exist would be to be to reject an axiom of their Weltanschauung.

- Failed matings. One argument contra the possible existence of such animals has been that some observed matings between equids and bovids failed to result in the production of hybrids. For example, in a case cited above, Buffon made much of the fact that matings between a bull and a mare had produced nothing. But evidence of this kind is of limited value. For, as everyone knows, not every mating leads to a pregnancy, even when hybridization is not in question. Indeed, in some cases even insemination many times repeated can fail to result in impregnation. And when hybridization actually is in question, more inseminations are typically required than in unmixed matings (McCarthy 2006).

- Difference. Another argument is that equids and bovids are too different in terms of their anatomy or in terms of evolutionary relationship to produce a hybrid. But the parents in a hybrid cross typically differ in anatomy, and it is unknown just how different two animals can be in terms of their anatomy if they are still to produce a hybrid. As to evolutionary relationship, in that case too, it is unknown how distantly related two hybridizing animals can be. But those who did accept this notion of the cross being precluded by distance would have likely been quicker to embrace the claim that many of the various alleged jumarts were simply deformed hinnies (since horse × donkey is a much closer cross).

- Genitals. Another, rather antique argument, which no one would take seriously today, is that the genitals of equids and bovids are too different to allow mating to occur. Haller, for example, mentioned this reservation in his correspondence with Charles Bonnet (Sonntag 1983, p. 1163). This notion is completely negated by the fact that both donkeys and horses have been many times observed copulating with cattle. Indeed, cases of hybridization are on record between parents differing greatly with respect, not only to the size of their genitals, but even with respect to body size as a whole. Male Steller sea-lions (Eumetopias jubatus) are about 10 times as large as female California sea-lions (Zalophus californianus), and yet natural hybrids occur (DeLong 1982, Gorodezky 1995, Miller 1996, pp. 471-472).

- Gestation periods. Some writers have argued that the production of hybrids from this cross is impossible because the gestation period of a horse (48 weeks) is a longer than that of a cow (39 weeks). During the course of my research into hybrids, I have often met with this assertion. It is, in fact, an age-old claim, dating back at least as far as Pliny the Elder (1st century A.D.). Counterexamples invalidate this line of argument. One well-established case is that of the cama, the hybrid of a dromedary camel and a llama. The former of these two parents has a gestation period of some 56 weeks, whereas the later has one 48 weeks. Another is the wolphin, the hybrid of a false killer whale, in which gestation lasts 67 weeks, and a bottle-nosed dolphin, in which it lasts only 50 weeks. In the latter case, the lengths of the parental gestation periods differ by four months, whereas the difference between horse and cattle is less than three. The domestic pig has a gestation period of 115 days, whereas that of the babirusa averages 153 (150-157 days), a difference of 33 percent, about the same, then, as that between dolphins and false killer whales (34%). And yet, they produce hybrids (Thomsen et al. 2011). So it seems this claim about gestation periods is just an old wive’s tale, repeated by scientists and non-scientists alike.

- Chromosomes. One reason someone today might cite for the impossibility of producing jumarts is that cattle, donkeys and horses have different chromosome numbers (2n=60, 2n=62 and 2n=64, respectively). But obviously, horses and donkeys produce hybrids together, and they differ no less with respect to chromosome count than do cattle and donkeys. Moreover, well-documented hybrids are known from many other types of mammalian crosses in which the parents differ more with respect to chromosome number than do equids and bovids. A few examples among many are: horse × zebra, ass × zebra, sheep × goat, and Indian muntjac × Chinese muntjac.

Theodor Kitt

Theodor Kitt1858–1941

More reports. Somewhat ironically, in the very year that Suchetet was assuring his readers of the impossibility of jumarts, American newspapers reported two separate cases of horse-cow hybrid. One was an animal, reportedly birthed in Jefferson County, Mississippi, that was like a horse except in having cowlike legs from the knee down, including cloven hooves on all four feet (see: the Hernando, Mississippi, DeSoto Times Jun. 12, 1890, p. 2, col. 2). Theodor Kitt (1858–1941), a German professor of veterinary medicine, described two separate cases that were the converse of the Mississippi case just described, viz., two animals with four hooves like a horse’s, but that was otherwise like a calf (Kitt 1885, vol. 11, p. 59, et seq.).

The other American case was a horse with fully developed horns and hooves like a cow’s. The Tombstone, Arizona, Epitaph (Jan. 25, 1890, p. 3, col. 6) carried the story:

And just three years later, we find a report about a cow calving, not one, but two perfectly viable offspring that looked for the most part like foals (Poverty Bay, New Zealand, Herald Jul. 18, 1893, p. 4, col. 1):

The mother is a young Jersey of unmixed breed and a valuable animal. As usual, the penny show proprietors have scented out the curiosities, and have proposed to purchase them, but the owner has declined, having a mind to watch the development of these singular offspring. The other cattle and horses on the farm alike refuse to consort with the strangers, and it has been found necessary to isolate them in a separate pasture. The colt-calves are playful little creatures, and seem to possess affectionate dispositions, coming to the bars at a whistle from the man having them in charge. Crowds from all over the country have been to see the curiosities.

And that same year a brief notice about a cow with a mane, and hooves like a horse, appeared in the Indianapolis, Indiana, News (Jul. 31, 1893, p. 4, col. 4):

Indeed, five years before Suchetet wrote his report rejecting the possibility of jumarts, a veterinary surgeon in the French army, Alphonse Barrier (1884, p. 490), published a detailed description of the solid-hoofed right forefoot of a bullock and concluded that “Altogether, the digital member of the subject individual is quite similar, both in form and anatomic structure, to that of a horse.”†

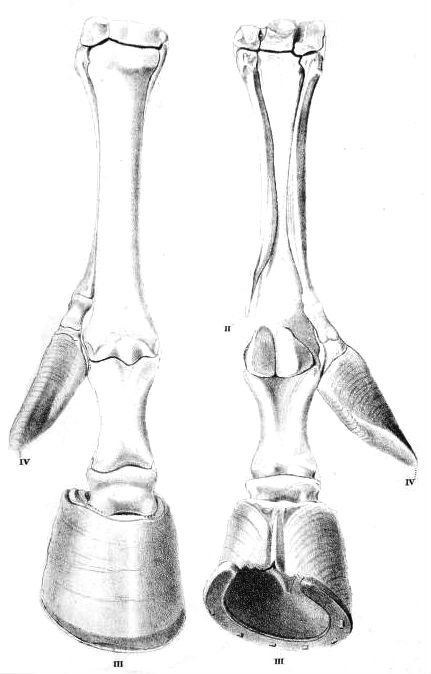

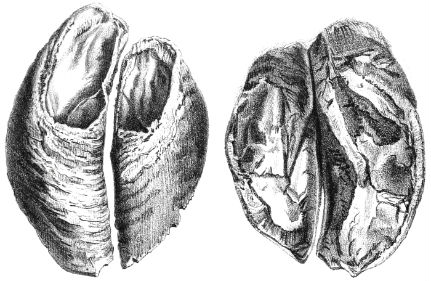

Forefoot, of an otherwise horselike animal, with a supernumerary digit bearing a cowlike hoof (Wood-Mason 1871, Plate 1). Arloing (1867, Plate 1) pictures an almost identical case.

Forefoot, of an otherwise horselike animal, with a supernumerary digit bearing a cowlike hoof (Wood-Mason 1871, Plate 1). Arloing (1867, Plate 1) pictures an almost identical case. Cowlike hooves from the right forefoot of an animal that otherwise had the appearance of a horse (Arloing 1867, Plate 2) Left: viewed from above. Right: viewed from below. Arloing (p. 69) says this individual lived five or six years, serving as a draft animal, before being sacrificed due to age.

Cowlike hooves from the right forefoot of an animal that otherwise had the appearance of a horse (Arloing 1867, Plate 2) Left: viewed from above. Right: viewed from below. Arloing (p. 69) says this individual lived five or six years, serving as a draft animal, before being sacrificed due to age.

Saturnin Arloing (1846-1911) was a well-known French veterinary surgeon (more information).

Saturnin Arloing (1846-1911) was a well-known French veterinary surgeon (more information). James Wood-Mason (1846-1893), an English zoologist, served as director of the Indian Museum at Calcutta (more information).

James Wood-Mason (1846-1893), an English zoologist, served as director of the Indian Museum at Calcutta (more information).

|

Twentieth Century

Occasional reports of such hybrids continued to be published on into the twentieth century. The following report appeared in the Salt Lake City, Nevada, Broad Ax (Aug. 3, 1901, p. 2, col. 4):

New Jersey Again in Line with Something Abnormal

The animal has attracted much attention, and several circus men have endeavored to buy her. The mare can get over the ground in lively fashion, while not appearing to be going fast. In the stall the animal chews her cud, as does a cow or bull, and if watched closely many of the attributes of the bovine can be observed. When swishing flies her motion is the same as that of a cow. She can gallop, but in a clumsy fashion only.

From the Ottumwa, Iowa, Semi-weekly Courier (Mar. 7, 1901, p. 7, col. 6):

Both Ottumwa and Decorah are in Iowa. The case described seems to be a mild case of cyclopia in which the eyes are adjacent, but not fully merged as a single eye.

The Princeton, Minnesota, Union (Oct. 8, 1903, p. 1) carried a report about a sideshow animal, described as a colt with cow hooves.

The following appeared in a South Carolina newspaper, the Keowee Courier (Feb. 22, 1905, p. 5, col. 1):

The following two reports, both involving a colt with a single hoof like that of a cow, recall the case described above by Gloag. The first, which describes an animal that was a viable cyclops, appeared in the Sheridan, Wyoming, Post (Oct. 12, 1906, p. 6):

Another report appeared in the Pullman, Washington, Herald (Apr. 25, 1908, p. 4, col. 4):

In a similar report, a pony foaled by a Shetland mare in Nevada, Iowa had three cow hooves instead of one. Taken here from the Monroe City, Missouri, Democrat (Jun. 11, 1908, p. 8, col. 1), the same story appeared in many other papers across the country.

Above: Ernst Friedrich Gurlt, who reported the converse of the case described at left, viz., an animal with three hooves like a horse’s, but that was otherwise like a calf (Gurlt 1832, vol. 2, p. 153).

Above: Ernst Friedrich Gurlt, who reported the converse of the case described at left, viz., an animal with three hooves like a horse’s, but that was otherwise like a calf (Gurlt 1832, vol. 2, p. 153).

Many have gazed upon the little curiosity, and all are unable to advance any satisfactory explanation for this freak of nature. At first Mr. Lash was inclined to kill the little fellow, but as the colt was strong and apparently able to make his way through the world all right, his neighbors prevailed upon him to save the little one. A great many people have called to see the freak.

Another case of a horse with cow hooves cantered onto the pages of the Jamestown, North Dakota, Weekly Alert (Jul. 17, 1902, p. 2, col. 4):

A horse-cow in Stratford, Connecticut, was mentioned in the Bridgeport, Connecticut Evening Farmer (Nov. 14, 1910, p. 8, col. 5):

An animal that reportedly combined the traits of a horse, cow, and deer is described in Appendix 6.

Tails of a horse and a cow.

Tails of a horse and a cow.

The following question from a reader appeared in the Seattle, Washington, Ranch (Mar. 1, 1911, p. 11, col. 1):

The Doniphan, Missouri, Ripley County Democrat (Aug. 15, 1913, p. 1, col. 3) carried the following notice:

In Canada, the Windsor, Ontario, Star (May 20, 1924, 1913, p. 1, col. 6; ||yxvpwhyf) carried a brief notice reading, “A foal with a cloven hoof has been born in Kent County.”

Some Austro-Hungarian reports. From the Bregenzer Tagblatt (Mar. 17, 1915, p. 3):

From the Pilsner Tagblatt (Jun. 4, 1917, p. 3):

From the Grazer Vorortezeitung (Oct. 28, 1917, p. 6):

Forefoot of a “foal” having a structure identical to that of a cow (from the collection of the Danish College of Vet. Medicine; see: Boas 1882, p. 280, pl. 11, fig. 9).

Forefoot of a “foal” having a structure identical to that of a cow (from the collection of the Danish College of Vet. Medicine; see: Boas 1882, p. 280, pl. 11, fig. 9).

As has already been mentioned, the gestation period of a cow is about 39 weeks, that of a horse, 48 weeks or more. So the length of gestation in this last-quoted case is intermediate between that of horse and cow. Hybrids typically have a gestation period intermediate in length between those of their parents.

Some Australian reports. From the Bombala, New South Wales, Times (Nov. 22, 1912, p. 4, col. 1):

The Inverell, New South Wales, Times (Feb. 3, 1922, p. 4, col. 2) ran this notice:

The Muswellbrook, New South Wales, Chronicle (Oct. 2, 1925. p. 8) told of a cow giving birth to an animal with horselike characteristics:

Although this last report states that the animal in question is the product of a cow mating with a bull, note that this is merely an assumption. Conceivably, the cow might already have been impregnated by a stallion when she was serviced by the supposed sire bull.

And the Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, Express (Feb. 3, 1934, p. 3, col. 3) briefly reported another case:

From the Lismore, New South Wales, Northern Star (Sep. 23, 1946, p. 7, col. 5):

Stunted and stump limbs seem to occur at higher rates in distant hybrids.

Barbed wire

Barbed wire An early tractor at work

An early tractor at work

Reports decline. As the twentieth century unfolded, reports about jumarts became increasingly scarce. This decline was probably due, at least in part, to a decrease in the rate at which such animals were produced. Barbed wire was first patented in the United States in 1867. The increasing use of this cheap fencing during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries drastically decreased the number of free-ranging animals worldwide. With the demise of the open range and the rise of the fence, animals became more segregated on farms and ranches, a trend that would reduce the opportunity for serendipitous matings between bovids and equids.

Also significant was the advent of the internal combustion engine. Horses and donkeys were more and more rarely used as sources of power, and they therefore became far rarer on farms. By the end of the thirties, very few of these animals remained on working farms, at least in developed countries, where they had all been replaced by tractors. So there was now little chance for them even to mate with cattle, let alone to produce jumarts.

Another factor, which may have been just as important as any actual decline in the rate at which jumarts were born, was a shift in attitude toward abnormal people and animals. The word freak is a shortening of the older term freak of nature, and in the early 19th century freak lacked the heavy negative connotation that it carries in the English language today. At that time it simply meant “whim” or “caprice.” The idea was that nature was doing something for no particular reason. Indeed, freak of nature is an English rendering of the older term lusus naturae, meaning a game or sport of nature. The notion was almost that a personified Nature, in creating abnormal organisms, was taking a break from the humdrum of her usual task of producing the normal creatures of the natural order.

A circus sideshow, circa 1900

A circus sideshow, circa 1900

However, this idea of a frisky Dame Nature, playing around with her creations, was gradually supplanted during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by the idea that abnormal individuals are the victims of mutations in their hereditary material. As such, they became objects of pity and their public display in sideshows and dime museums came to be viewed as cruel and immoral. Likewise, under this new view, it was judged insensitive and even disgusting to speak of them in newspapers and other sources of information. Where freaks had once been family entertainment appropriate even for the eyes of children, they were now something near obscenity, abhorred by all. With these changes in mentality, freak came to have the very negative connotation that it still carries today.

This marked shift in attitude brought legislation placing outright bans on the public display of freaks in many places. For example, at the beginning of the twentieth century, an Indiana newspaper, the New Richmond Record (Oct. 25, 1900. p. 2, col. 2) was advocating that freak shows be banned by law.

Increasingly, such statutes were in fact put in place, and with time and in the absence of venues where people could witness living evidence to the contrary, prevailing notions of what was possible became less and less tempered by direct observation. It became the “educated” attitude to dismiss the aberrant as impossible, though such claims are more comfortable than they are rational. In The Lord of the Rings, Galadriel says,

Old reports about jumarts have been forgotten. The old sideshows have largely been lost. And modern-minded journalists and scientists describe horse-cows as myth and therefore never write about them or investigate them, except with a certain bemused regret for the supposedly benighted ideas of a day gone by. Because they conceive of the jumart as being strictly the stuff of legend, they never voice doubts about whether such creatures might indeed be real, especially given that the topic of freaks is now so widely judged in bad taste. So in our modern world any living jumarts would but rarely ever come before the public eye. But rarely is not the same as never. A few reports do evade the net of dismissal, disgust and distain.

Boston, U.K. Thus, an animal in a relatively recent news report appears to be a horse-cow hybrid. It belonged to Frans Buitelaar, a Boston, U.K., meat dealer during the 1960s and 70s, and is pictured in an online article in the Boston Standard. According to the brief comments accompanying the picture, a local vet was consulted at the time and he pronounced the animal “bovine.” However, might it not also have been equine? The Standard’s image is shown below. Traits visible in the picture that seem consistent with the idea that this animal has equine inheritance are: (1) its very horse-like tail; (2) the rounded hindquarters (i.e., croup) region, which does not at all have the pointed shape characteristic of a cow; (3) absence of an udder; (4) saddle in the back, unlike the straight back of a cow; (5) long, thick horse-like neck.

Although the former owner Frans Buitelaar is now deceased, his son, Adam Buitelaar, when contacted (Oct. 22, 2016), said he remembers seeing the living animal and confirmed it did look like the creature shown in the image above. And he clearly remembered it having a horse’s tail. He also said that it was a female, which would make the fact that it lacked an udder very peculiar indeed—if it were a pure cow. Moreover, the animals shown in the videos cited above have a similar structure, and videos are far more difficult to fake than photos.

A jumart (Houël, 1766)

A jumart (Houël, 1766)

Variability. It can be seen that the Buitelaar animal differs substantially from the creature shown in Jean-Pierre Houël’s eighteenth-century illustration (shown at right), which was allegedly drawn from life at the l’Ecole d’Alfort in 1766. Note that the Alfort animal has a cow-like tail and hindquarters, unlike the animal pictured by Buffon, the Buitelaar animal, and two of the three animals shown in the videos above, which all have tails like that of a horse. One of the three animals shown in the video, however, does have a cow-like tail. This discrepancy may simply reflect a high order of variability in the offspring from this cross, as is the case with certain other distant hybrid crosses. And some authors do say that jumarts, specifically, are variable. Thus, in his encyclopedia of agriculture, François Rozier (1793, vol. 6, p. 117, s.v. jumart) states that not all jumarts are the same, with some exhibiting more bovine traits, others, more of the equine. Certainly, the descriptions of animals given in the reports cited above describe animals that vary quite widely.

Thus, on the one hand, the structure of the Buitelaar animal is consistent with the brief descriptions of the Buchau, Neudorf and Colby animals in that the equine similarity is primarily restricted to the hindquarters and tail. The same can be seen in two of the Kitale animals shown in the videos above.

On the other hand, the Mountain Rest, Elizabethport and Friedingen animals were reported to have the reverse configuration, that is, they were described as horse-like anteriorly and cow-like posteriorly. And then, some of the early French cases and the New Zealand animals, from their descriptions, seem to have been of an equine character overall. There are also the two animals born in the U.S. in 1908, which looked like ordinary colts, except that one supposedly had a single foot like that of a cow—as did the animal described by Gloag—while the other had three.

If we are to presume that these various reported animals were hybrids, then it would seem reasonable to conclude, too, that they were first-generation (F₁) hybrids. Otherwise, one would have to assume that hybrids from this distant cross can sometimes produce offspring. But if they were in fact all F₁ hybrids, then it is unclear why jumarts should be so variable. In closer crosses, F₁ hybrids typically show very little variability in comparison with that seen in later generations, where the effects of meiotic recombination come into play. Therefore, the variability so evident in the reported animals seems to point to the existence of some as yet unknown developmental mechanism.

It is possible, however, that at least some of the reported variability may result from different parents being used in the differing cases, that is, some may involve jackass with cow, others, bull with jennet, others, stallion with cow, etc. The breeds mated would also have differed in the various cases described.

Conclusions. Genetic testing of the alleged jumart skull held in the Musée Fragonard’s collection, and of the two Kitale animals, would help to resolve the question of whether hybridization between cow and horse is possible. Given that these specimens would all presumably be F₁ hybrids, if they are hybrids at all, such testing would be straightforward. Such a study could have potentially important implications, in that any definite verification that any of these specimens were derived from hybridization between an equid and a bovid would demonstrate that the limits of mammalian hybridization extend well beyond what biologists generally believe possible. In the minds of many scientists, those limits at present seem to extend only as far as intergeneric crosses (Savriama et al. 2018), whereas, as has already been mentioned, a cross between an equid and a bovid would be interordinal (Perissodactyla × Artiodactyla).

But given even the evidence collected here, it seems probable not only that it is possible to produce hybrids between cattle and equids, but also that such births have actually occurred. One might conceivably take the position that all of the many reports about these animals are merely mistaken, or even somehow faked. But where there is so much smoke, it does seem that a certain amount of combustion must be present.

A turkey-chicken hybrid (Olsen 1960).

A turkey-chicken hybrid (Olsen 1960).

The situation may well parallel that seen in other, better studied, distant crosses, in which a large number of inseminations are required to produce a single viable hybrid. For example, when rooster semen was used to inseminate turkeys, Olsen (1960) found 302 embryos (14.2%) among 2,132 eggs incubated. Of these, only 120 attained an age at which the color of the down could be used to establish that hybridization had occurred. Only 23 of these hybrids actually hatched, and just four managed to exceed an age of 9 weeks. These results suggest, then, that on average about 500 inseminations would be needed to produce a single mature turkey-chicken hybrid. Sarvella (1971) obtained similar results for quail-pheasant hybrids (Coturnix japonica × Phasianus colchicus). In that cross, after artificial insemination, only about six percent of eggs are fertile. Of these, about one in six hatch and only about one in 20 of those that hatch reach adulthood. So about 2,000 inseminations are required to produce a single mature hybrid.

From the standpoint of the taxonomic classification, a cross between an equid and a bovid would, if anything, be even more distant than that between chicken and turkey or between a quail and a turkey. Therefore the number of inseminations required might be even higher. And in fact, as has already been mentioned, Suchetet (1890, p. 19) says one of the reasons that farmers hesitated to attempt to produce this cross was a low conception rate (“les chances de nonréussite dans des accouplements aussi disproportionnés”). This fact should be kept in mind by any researchers who might choose to investigate this cross by means of artificial insemination or through experimental matings.

This page was a draft for a chapter of my now-finished book on distant hybrids, available here >>

Appendix 1

Names

The word jumart was taken into English from French around 1700. The word jumart is perhaps a derivative of the similar French word jument (“mare”), which in turn is related to Latin iumentum (“mule” or “beast of burden”). Also the word iumar, meaning “jumart,” occurs in Latin. In French, the suffixes -ard and -art, especially the former, are used to form nouns and adjectives, often with diminutive or pejorative meanings.So jumart could have been derived from jument or iumar by adding -ard/-art to yield jumard or jumart Both forms exist in French (also joumard). A parallel exists in the Italian words for mare (giumenta) and jumart (guimerro). Many names have been used, in various languages, to refer to hybrids of this sort. Among them are the following:

- · French: jumart, jumard, jumar, joumar, joumard, gemart, gemard, gemar, gimar, baf;§ bif,§ hippobus, hippotaure, onotaure, juméry;

- · Valéian: jumerre;‡

- · Languedocien: jhimêrë, jhimêrou, jumeri, gimerou, gimere, gimeri

- · English: jumart

- · Latin: iumar, iumarus, hippotaurus, onotaurus, hippobus, iumar

- · Spanish: hippotauro, onotauro

- · Portuguese: jumardo

- · Dutch: Muilpaard (-en)

- · German: Ochsenpferd (-e), Ochsenesel (-n),

Maulochs (-en), Jumar (-n), Gemar,

Jumarre, Jumarra;

- · Italian: giumarro (-i), giumerro (-i), gimerro (-i), ippobo (-i), bosmulo (-i);

- · Arabic (according to Shaw): kumrah or koomrah.

§ The Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française (Suppl. 3, 1836, Paris, pp. 73 & 91) states that the French word bif signifies a jumart derived from crossing a bull with either a mare or a jennet, whereas baf means one from a cross between a cow and either a stallion or a jackass. However, Leger (1669) and Valmont de Bomere (1775, vol. 3, p. 512, s.v. jumart) say that a baf results from crossing a bull with a mare, but a bif, from a bull with a jennet. So there appears to be some confusion on this point.

‡ Valéian is the dialect of Occitan spoken in the Ubaye Valley (French: Vallée de l’Ubaye, formerly, Vallée de Barcelonnette).

Appendix 2

Original French of a now-defunct page of the Musée Fragonard d’Alfort website, quoted in translation above

"Les monstruosités furent relativement peu étudiées au début des Écoles Vétérinaires, mais il est une exception qui suscita une longue polémique: le jumard (ou jumart, ou joumart). Cet animal, censé être issu de l’accouplement d’un bovin et d’un équin, fut abondamment décrit par Bourgelat qui usa de toute son aura pour faire accepter l’idée du croisement inter-espèce. Il en fit une description précise dans une correspondance qu’il entretint avec le naturaliste Charles Bonnet; cette jumart (ou jumarre) était très forte. Son front, son mufle et sa mâchoire inférieure étaient ceux d’une vache, mais la denture et la matrice celles d’une jument. Fait marquant, l’animal ne possédait pas de vésicule biliaire. Autre part, Bourgelat affirmait avoir produit un jumard en mettant un étalon navarrain avec une vache. Il ne vécut que quatre mois et était plus proche de la mère que du père. Le créateur des Écoles Vétérinaires signalait que plusieurs cas avaient été présentés à l’Ecole de Lyon et que le Dauphiné était certainement une région particulièrement propice à leur génération. Le jumard devint l’objet d’un vaste débat dans lequel les plus grands noms de la biologie de l’époque affirmèrent leur opinion. Buffon, dans le Supplément à l’histoire des quadrupèdes, reconnaît que la jument et le taureau peuvent s’accoupler malgré des organes génitaux différents. Il rapporte avoir vu en 1767, chez son meunier, deux à trois accouplements par jours sans qu’aucune naissance n’en ait jamais résulté. Le jumart lui paraissait être un animal chimérique même si le croisement inter-espèce s’avérait possible, comme par exemple celui de la louve et du chien. Garsault, Haller, Huzard se rendirent à son avis et cette opinion finit par triompher après près d’un siècle de polémique. Le Musée Fragonard conserve encore une tête osseuse de jumard datant de l’époque de Bourgelat. Le crâne est globuleux; l’animal est brachignathe supérieur; les incisives supérieures sont déportées en arrière."

Appendix 3

Thomas Sedgwick Whalley’s description of his journey on a jumart

Thomas Sedgwick Whalley

Thomas Sedgwick Whalley