Weapon of war, language-game, act of restorative justice, conversation – erasure poetry can play all these parts and more. A branch of found poetry, erasure poetry starts from an existent document, obliterating parts of it to leave a new, slimmer text. While this type of verse is seeing a surge in popularity due to its “instagrammable” nature, cut-up and collage techniques have been around since the mid-20th century. And parody, the mockery of another poem by borrowing words and ideas and giving them a comic twist, must have existed long before poems were even written down.

There’s no one way to create an erasure poem. The only “rule” is that words must be taken away from a pre-existing text, rather than written as new. American poet Erin Dorney defined six different kinds of erasure poetry in a 2018 blogpost. “Crossouts”, where sections of newspaper articles or documents to make a poem out of the remaining text, are probably the best-known type, popularised by Austin Kleon’s Newspaper Blackout Poems. Other authors have been more creative in how they block out text, using things such as sand and flowers to obliterate the chosen passages. An Instagram poem Dorney quotes, by Jaime Mortara, blacks out all the surrounding text, ending up with “my brain / is / a / stunning / joke”. Many erasure poems offer such cryptic snatches of wisdom, wry quips given significance by their spotlighting.

At its best, erasure poetry goes far beyond the playful. In her poem cycle, Zong!, M NourbeSe Philip uses period court reports to expose the case of the 18th-century slave ship that jettisoned 150 live enslaved Africans in order to collect insurance. Philip, as she says, “murders the text”. Her poems overturn conventional syntax, and tear words into pieces to create emblematic and indeed audible expressions of anguish and abuse. It’s as if the demolition of a statue had become an art form that could reveal every micro-cruelty committed in the name of the person commemorated.

Cruelty and ignorance are targets too for Raymond Antrobus, poet-advocate for the D/deaf community. Antrobus made a powerful statement against the ignorance he perceived in Ted Hughes’s poem Deaf School when he included it, fully redacted, in his (Ted Hughes award-winning) collection The Perseverance.

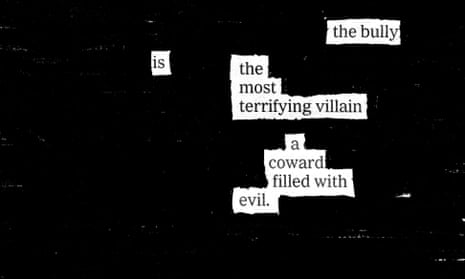

Kate Baer, author of the New York Times bestseller What Kind of Woman, takes an almost conversational approach to erasure in her new collection, I Hope This Finds You Well. Baer’s strategy was to “write back” to the trolls and bigots on her blog, using the erasure technique to turn dead wood into spiky poems. Previously, she had always deleted abusive comments. But when one day she read a message from a woman who disagreed with her about police accountability, she says “the words stuck out to me in a new form”.

“On a whim I took a screen shot of her message, blotted out some lines with the pen tool, and hit post,” she explains. The context of the resulting poem, Re: Holding Police Accountable, was George Floyd’s murder.

The original message read: “I wish you would stick to poetry instead of constantly being political, just one reader preference / Have you ever thought what would happen if the police disappeared? / Is what you say going to change anything? (No) / when you stay in your lane, better connection happens / I know staying silent isn’t cool but just a thought.”

“I wish you would // disappear / is what you say / when you stay / silent” is Baer’s riposte.

Not all the messages are hostile, and Baer replies kindly when the writer is sympathetic. When a fan complains about the difficulty of most other poetry, her response is: “I wanted art / poetry was / hidden / in / so much / in so many ways.” And poetic artistry remains important to her. She speaks for her community as well as herself when she says: “My hope is that by sharing these pieces we continue to hold on to the truths that sustain us, and when we do encounter the inevitable noise – we tune our ears to hear the song”.

Erasure poetry, Baer’s included, is rarely just a “song”. The poet Jennifer S Cheng, writing in Jacket2, said that “perhaps erasure poetry is always inherently a political act, perhaps it is always inherently a violent act”. The former is surely right: language is political, and writing with a doubled context doubles that resonance. Erasure can be an ugly weapon. It can distort and destroy another writer’s work. There are certainly ethical issues to consider when text by another author is repurposed. But the “violence” may also take positive forms by showing how easily ideal can slide into injustice, as when Tracy K Smith, in her poem Declaration, scaldingly revises the US Declaration of Independence.

While some kinds of erasure poetry are enabled by Instagram, a medium not usually associated with the art of close reading, erasure can be a delicate, non-lethal probe rather than a weapon. Especially when challenging dust-thick prejudice and received opinion, it has the potential to be transformative.