In the months after Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, Aleksandr Averjanov lost his motivation for playing games on Chess.com. Known for its strong community and livestreamed competitions, which feature some of the best chess players in the world, the website is the world’s largest online chess platform. But as the war intensified, Russian players faced exclusion from online tournaments and were shut out by other teams, said Averjanov, who is based in Moscow and plays under the username Alex-04.

Then, on Saturday, April 23, Roskomnadzor, Russia’s media supervision agency, which is responsible for censorship, blocked access to Chess.com after the platform stated its support of Ukraine.

“We just wanted to play chess, and we were dragged into an information war,” Averjanov said, who is still playing on Chess.com through a virtual private network (VPN).

Since the start of Russia’s war against Ukraine, Roskomnadzor has banned online services including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Google News, and many Western media outlets. On Chess.com, Roskomnadzor blocked two blog posts related to the Ukraine war: a statement that detailed Chess.com’s condemnation of the invasion and support for Ukraine, and a news piece that interviewed Ukrainian chess players. But because Chess.com uses the HTTPS protocol, the block resulted in the ban of the entire site.

The ban has left Russian users dissatisfied. Chess is an important sport in Russian culture, and many of the country’s top players use Chess.com. On VKontakte, some players blame the platform, but many more are simply frustrated with the ban.

“It’s bizarre and would be very noteworthy under any kind of normal circumstances,” Peter Svidler, a Russian chess grandmaster and an eight-time Russian Chess Champion, told Rest of World. “These aren’t normal circumstances.”

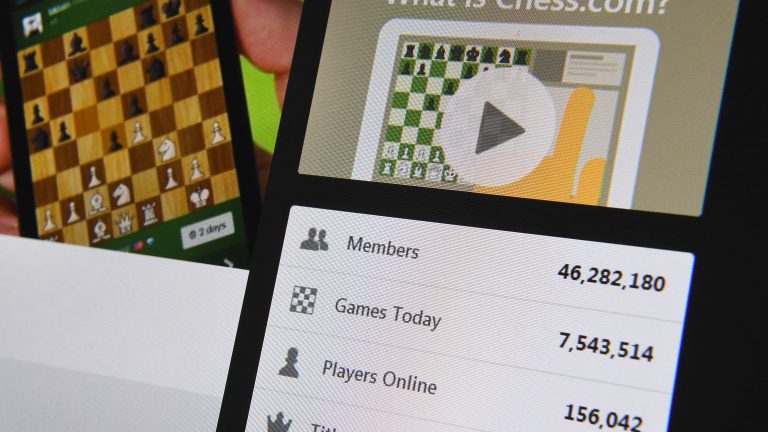

Based in Mountain View, California, Chess.com was co-founded by CEO Erik Allebest in 2007. Allebest told Rest of World that Chess.com was his third chess-related business, envisioned as a “MySpace of chess.” The platform, which attracts the spectrum of players from beginners to the world’s top chess grandmasters, now has just over 80 million members. “Sometimes I’m surprised at our own size,” Allebest said.

Player names on Chess.com are presented alongside a small flag icon, indicating a player’s origin or an organization they are associated with. For Allebest, part of the attraction of the platform is connecting players from different backgrounds. “Chess has two colors, you’re white or you’re black,” he said. “It’s a place where [players] can go and they can meet people from other countries – or not. You don’t necessarily know the race or gender or sexual orientation or political views of the person that’s across the board from you, and you just have, like, a real human moment.”

But as a platform with a global community, the company is no stranger to navigating tensions between national identities. It has previously sparked anger for offering Palestinian, Macedonian, and Catalonian flags.

Among Chess.com’s users, 3.5 million identify as Russian. Since the start of the war, the company has received both pressure to ban Russian users and appeals from the Russian Chess.com community to keep politics out of the game, said Allebest.

“A lot of chess players left the platform out of protest, so there wasn’t any motivation to play.”

In response to the invasion of Ukraine in February, Chess.com posted a statement outlining its position and policies on the matter. It wrote that it condemned the invasion and supported Ukraine, and that its priority was to support its own workers in the country.

It also explained that it had decided to remove Russian flags from players’ icons, a decision that the CEO told Rest of World was meant to be a “reasonable place in the middle” between two extremes. It was also meant as a message that the platform acknowledges the crime and the pain caused by Russia, he said. “It became clear that Russians also didn’t really understand the scope of what was happening,” he added.

Many Russian players took issue with the move. Kirill Shcherbinin, Candidate Master chess player and one of the admins of the Chess.com Russian national team, said he respected Chess.com’s position on the war, but felt that the decision to remove flags was drastic. “Removing the flag is the destruction of a certain part of the user’s self-identification,” he told Rest of World. Chess players competing in international tournaments consider the flag an important part of their identity, and some Russian players will decline to play without it, he said. “The suspension of the participation of the Russian team, as well as teams in the leagues, is certainly a sad event, both for Russian players and for the prestige of these tournaments,” he said.

Averjanov, who is the main administrator of Team Moscow, ended up changing his flag to the Belarusian one. But he said that his team was excluded from participating in two city-level tournaments. Even before Roskomnadzor decided to ban the site, the morale was low, he said: “A lot of chess players left the platform out of protest, so there wasn’t any motivation to play.”

Other users spoke of being confronted in chat rooms and private messages over Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

In its statement, Chess.com said that players under international sanctions would be banned; it wrote that it had “identified and closed accounts from multiple sanctioned Russian oligarchs.” It also said that those who supported the war would not be able to participate in prize events. This included 32-year-old Sergey Karjakin, who is a household name in Russia and a pro-Putin chess grandmaster who formerly held the record for being the world’s youngest ever grandmaster. It was Karjakin who called on Roskomnadzor to block Chess.com, which he accused in a Telegram post of spreading propaganda. Karjakin’s closeness to President Vladimir Putin resulted in an unprecedented six-month ban by world chess governing body FIDE.

Despite Roskomnadzor’s ban on Chess.com, some big-name players are still appearing in the site’s tournaments, and Allebest said that the platform has not seen a major drop in Russian users. As online censorship has heightened in Russia, many citizens have equipped themselves with circumvention tools such as VPNs. But the ban has made the platform trickier to use, and some are now moving to its competitor Lichess.org.

“Roskomnadzor successfully made [the] lives of their countrymen somewhat worse — not by a huge margin compared to everything else that’s been going on, but worse nonetheless,” Svidler told Rest of World over Telegram. For him, playing chess amid the upheaval “no longer feels right.” He was one of 44 Russian chess players to sign an open letter to President Putin opposing the war in Ukraine in early March. He said that he pretty much stopped playing on Feb 24, the day of the invasion: “[It] felt irrelevant.”