I am a former Facebook employee who was fired in September 2020, after working for over two and a half years as a member of the fake engagement team. I became a whistleblower earlier this year.

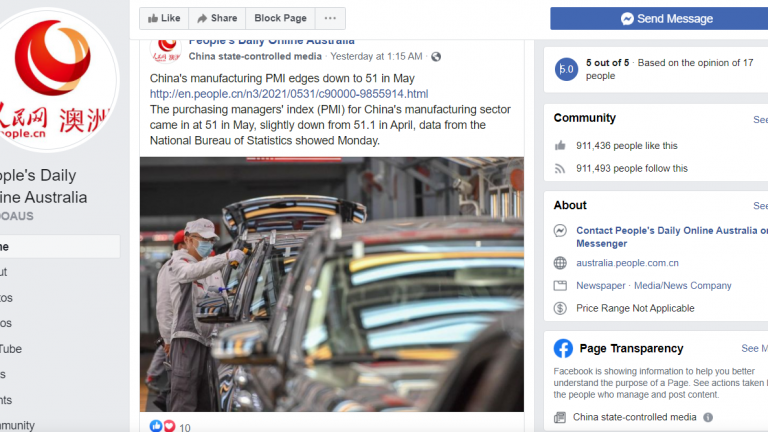

While my work at Facebook protecting elections and civic discourse has been widely reported on, that was conducted in my spare time. My actual job and team focused on stopping the use of inauthentic accounts to create engagement through likes, comments, shares, fans, and more. Such accounts are rare in the West, but common in the Global South.

During my time at Facebook, I saw compromised accounts functioning in droves in Latin America, Asia, and elsewhere. Most of these accounts were commandeered through autolikers: online programs which promise users automatic likes and other engagement for their posts. Signing up for the autoliker, however, requires the user to hand over account access. Then, these accounts join a bot farm, where their likes and comments are delivered to other autoliker users, or sold en masse, even while the original user maintains ownership of the account. Although motivated by money rather than politics — and far less sophisticated than government-run human troll farms — the sheer quantity of these autoliker programs can be dangerous.

Self-compromise was a widespread problem, and possibly the largest single source of existing inauthentic activity on Facebook during my time there. While actual fake accounts can be banned, Facebook is unwilling to disable the accounts of real users who share their accounts with a bot farm.

The presence of such accounts poses considerable risk to political discourse in the Global South, even if that is not their main use. For instance, political actors in Brazil were able to cheaply obtain inauthentic activity from the accounts of real, self-compromised Brazilians in the 2018 Brazil general elections before I fought to take that activity down. During the 2018 elections, I removed 10.5 million fake reactions and fans from political pages both in Brazil, and to a lesser extent, the United States.

Now, there’s a few things to keep in mind: 10.5 million fake reactions may sound like an impossibly large and impactful number, but this is the nature of an abuse vector that relies on creating large amounts of low-quality scripted activity. Brute force computer scripts excel at producing large amounts of activity, but they are often stupid and inefficient. To use an analogy, if Rest of World chose to replace its reporters with simple computer scripts, it could produce a far larger quantity of articles — yet its overall readership and impact would likely decline. Although the sheer quantity of such Facebook activity can add up to a significant effect, it should not be confused with or treated as seriously as the far more sophisticated troll farms.

Another element to keep in mind: Observers commonly conflate the use of inauthentic accounts with misinformation, two separate and largely unrelated problems. Misinformation is a function of what the person is saying, and does not depend on who the person is. If someone said the moon is made of cheese, this is misinformation, regardless of who’s saying it. Inauthenticity depends only on the identity of the user, regardless of what they are saying. If I have 50 fake accounts telling the world “cats are adorable,” this is still inauthentic activity, even though there’s nothing wrong with saying that. Although misinformation is a serious problem, it is not one that I personally worked on.

And finally, people often assume that inauthentic activity is political; their minds jump to the specter of Russia’s interference in the 2016 U.S. elections. But most people are not politicians, and most activity on Facebook is personal rather than political. People post everyday things: wedding photos, job changes, their thoughts and hopes. Fake engagement that has to do with politics makes up less than 1% of fake engagement on Facebook — and even that is largely automated. This scripted activity is separate from the more sophisticated troll farms of real individuals run by nations such as Honduras and Azerbaijan that I worked on in my spare time.

All that said, self-compromised accounts are still a problem. They degrade the trust of users in what they can believe online. Increasingly, Facebook users are concerned that others are gaming the system. Businesses worry that they may be paying influencers to share their content with followers, who are actually fake. And users who do not cheat the system find themselves struggling to compete with those who do.

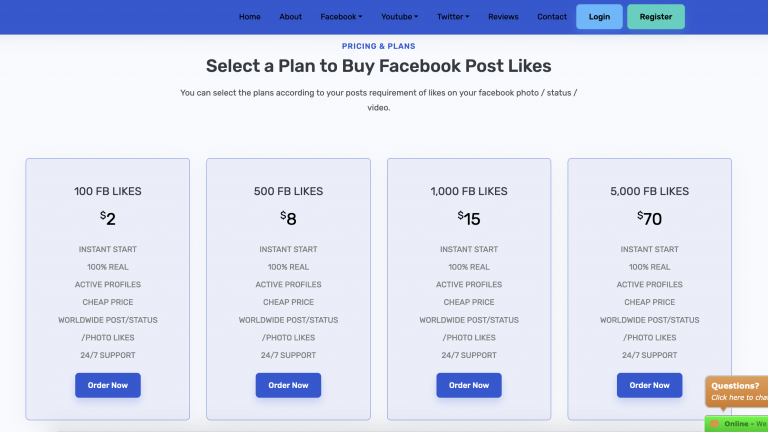

How do everyday users get caught up in autoliker programs? More often than not, the culprit is personal vanity. Many of the people who seek out fake engagement on Facebook are everyday users who go on the platform, make a post about their life, and see it only receive five likes, while their friend’s post has 50. And so they go on the internet and search “get Facebook likes,” hoping to solve their problem. To quote one user who had self-compromised in an internal 2017 research study, “I’m extremely attractive! I’m extremely talented – but I don’t have all those followers I deserve.”

One might naively assume that self-compromise is rare, and that most inauthentic accounts are fake, but in fact it’s the opposite. In the first half of 2019, we knew internally that there were roughly 3 million known fake engagers on Facebook, of whom only 17% were believed to be fake accounts. We believed the other 83% were largely self-compromised — many of them through autolikers.

To use an autoliker, users are required to provide their access token — a securely generated string that provides account access, allowing the attacker to login as the user. In exchange, the user is provided with free likes, comments, and shares on posts or pages of their choice. This engagement comes from other individuals who gave over their access tokens. The attackers generally monetize by selling additional activity on internet marketplaces.

Facebook users often don’t know what an access token is, and naively believe that they are safe because they have not provided their password. They may believe that they’ve gotten a service for free. In fact, they’ve paid by granting access to their own accounts. In other cases, users may be aware they’ve granted full access, but incorrectly trust the autolikers to act as reputable businesses.

Autolikers are conducting activity that violates Facebook policies, and I heard anecdotal evidence of autoliker accounts taking liberties with the accounts they’ve taken over. During my time at Facebook, I heard reports of autolikers using compromised accounts to seize ownership of prominent pages.

The irony is that signing up for autolikers is generally counterproductive for everything beyond vanity. Although our testers noted that there is a real psychological rush from seeing hundreds of likes suddenly roll into your posts, fake accounts produce no real activity. Self-compromised users are no more likely to be interested in the recipient than an average person on the street.

Individual Facebook users sign up for autolikers simply because they wish to be popular. This arrangement seems to deliver benefits to both themselves and the autolike business — but only because the costs are borne by others. They do not realize that they are contributing to the gradual erosion of trust in their fellow users and organizations, and corrupting the civic discourse in their nation.