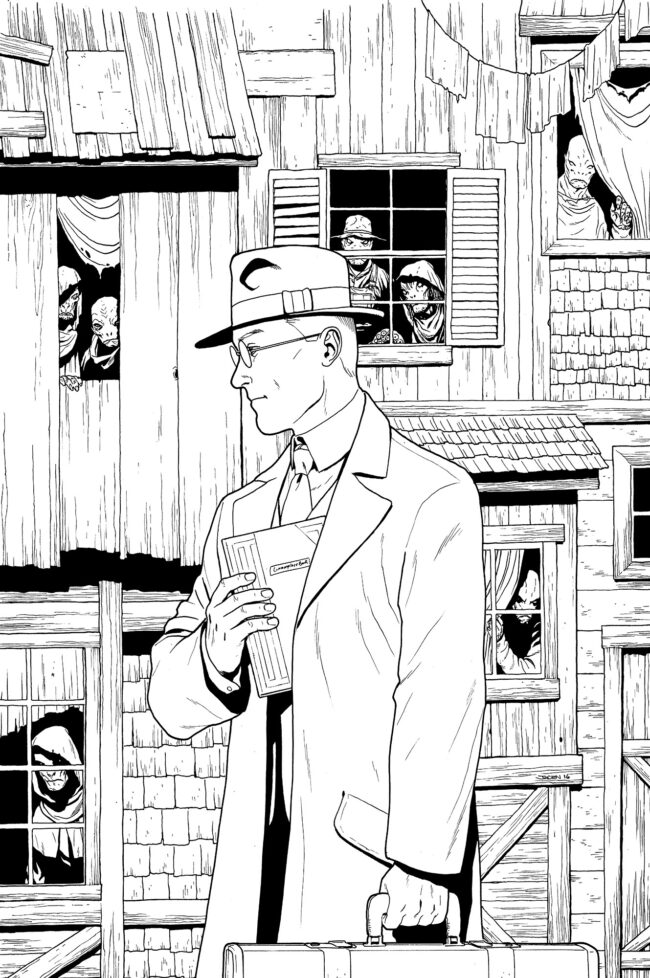

Jacen Burrows spent nearly two decades working at Avatar Press, where he collaborated with some of the most well known writers in comics including Warren Ellis (Dark Blue, Scars), Garth Ennis (303, Crossed), and Antony Johnston (The Courtyard), but Burrows remains best known for his collaborations with Alan Moore. Their first project, the miniseries Neonomicon was a dark Lovecraftian tale, but in the 12 issue series Providence, Moore and Burrows tackled Lovecraft the man, the period in which he lived, and tried to understand and push the mythos to its ultimate, horrifying, logical conclusion. It was disturbing and brilliant and stunning on many levels and Burrows rose to the challenge, going from detailed heavily researched depictions to moments of horrifying brutality, in the best work of his career to date, a lot of which can be seen in the art book Dreadful Beauty.

Jacen Burrows spent nearly two decades working at Avatar Press, where he collaborated with some of the most well known writers in comics including Warren Ellis (Dark Blue, Scars), Garth Ennis (303, Crossed), and Antony Johnston (The Courtyard), but Burrows remains best known for his collaborations with Alan Moore. Their first project, the miniseries Neonomicon was a dark Lovecraftian tale, but in the 12 issue series Providence, Moore and Burrows tackled Lovecraft the man, the period in which he lived, and tried to understand and push the mythos to its ultimate, horrifying, logical conclusion. It was disturbing and brilliant and stunning on many levels and Burrows rose to the challenge, going from detailed heavily researched depictions to moments of horrifying brutality, in the best work of his career to date, a lot of which can be seen in the art book Dreadful Beauty.

In the years since, Burrows has primarily been working at Marvel Comics, drawing a new Moon Knight series, and most recently re-teaming with Ennis on Punisher: Soviet, which is a favorite recent comic of multiple TCJ writers. His next project, working with Kieron Gillen on a Warhammer 40,000 comic was recently announced and we spoke recently over e-mail about his life and career.

I know that you went to Savannah College of Art and Design. Did you go there for comics? What was art school like for you?

I originally went to SCAD for Illustration. The SeqArt department opened up the year I arrived. I originally thought that Illustration would be more practical so I could work in a variety of industries but I've been sure I wanted to draw comics since I was 12. It eventually dawned on me that I would be happiest just focusing on the area I was passionate about instead. Illustration was really mostly focused on mastering the different art mediums, like painting, tech drawing, early computer art programs, while SeqArt was focused on storytelling. That distinction made all the difference. And I enjoyed Art School but I still don't think it was worth the price, since you aren't taught how to do things so much as paying for the opportunity to make art full time for a few years and teaching yourself. It is nice being surrounded by other artists, though. I did enjoy being around people from different disciplines and the focus on Art History and Culture was cool but it wasn't worth the price. I don’t think I’ll ever be done paying those loans and that was back when it was a LOT cheaper than it is now.

When you got out of college, you were working as an illustrator. What were you doing and what were you interested in doing?

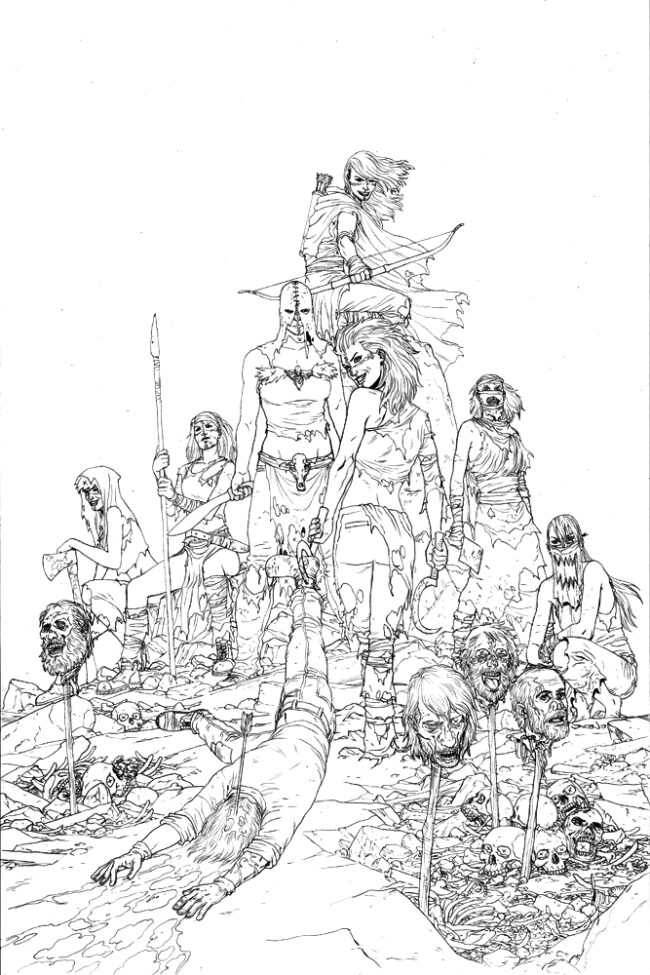

Even before college, I had done some (not so great) work for small publishers like London Night Studios so I still had some contacts and landed some quick gigs. Nothing notable to begin with. But the industry was in freefall right when I graduated so to make money I found employment working for various TTRPG companies. I was following in the footsteps of one of my comic heroes, Tim Truman, who I had first noticed when he worked for TSR on Dungeons and Dragons. I also stumbled into some fun side work in video games, doing a few jobs for Id Software and Rockstar Games. But the thing that really started my comic career was a weird sci-fi, post apocalyptic series called Skid Rose for London Night Studios with my friend, writer Miles Gunter. We were free to get as crazy as we wanted with it and even though it only got 2 issues before lack of payment ended the project, it got the attention of some people and led to getting King Zombie for Caliber, a sequel to Deadworld. From there it was on to Avatar.

I would have guessed you were a Tim Truman fan. Was a lot of your aesthetic and tastes shaped by eighties and nineties indie comics?

Definitely. I didn't start really getting into comics until I met a few other kids in middle school that were already heavily into collecting. I didn't really want to start trying to collect things with hundreds of issues right out of the gate so I started with things that were new and exciting to me, like TMNT, Grimjack, Grendel, stuff like that. Once I had the bug I expanded to more mainstream stuff but even there, I mostly stuck to the edges. I collected Punisher, Vigilante, Miller's Daredevil stuff, but the indies were my bread and butter. The more pulpy and hardcore, the better.

So what was your first published comics work?

I believe my first published comic work was a Razor story in London Night's Tour of Fear convention book in the early 90's. But even before that, I had gotten a gig while still in high school, drawing an epic 6 issue crossover series for Greater Mercury Comics, after I met publisher Kris SIlver at a convention. I think I drew maybe 3 issues of that but they never saw the light of day. I’m sure I would find that work incredibly cringe-worthy now. Talk about a blast from the past!

King Zombie with Tom Sniegoski at Caliber is the first comic of yours I have, but it wasn’t the first time you penciled a book.

King Zombie with Tom Sniegoski at Caliber is the first comic of yours I have, but it wasn’t the first time you penciled a book.

No, but that book was the first that had an audience. Not enough to keep the book going. I think I was halfway into the 3rd issue when Caliber went under, but it was a lot fun. And by then I was getting used to publishers shutting down while I was mid-project. It happened with Greater Mercury, London Night, TSR, and West End Games.

Around the same you were drawing The Ravening in Avatar’s Threshold anthology. Did that come out doing covers for Avatar? Or the other way around?

Tom Sniegoski, the writer for King Zombie, was pitching series ideas to William Christensen at Avatar right as Caliber closed shop and brought me with him. The first thing we did was a character called the Cimmerian (not Conan related) that had a series of short stories that ran in Threshold, the anthology. While I was working on those, William offered me extra work, which turned out to be those Ravening shorts that also ran in Threshold, along with random variant covers, as Avatar was prone to publish. I have to admit, even though the content left a lot to be desired, I really enjoyed the short 5-10 page format as a way to work on my penciling skills and storytelling. They were a good experience despite being trashy Bad Girl stuff.

How did you end up drawing Dark Blue?

Warren Ellis was, at that time, looking for places to do creator-owned shorts. I assume he was looking for a place where he could do edgier stuff than most existing creator-owned outlets were interested in at the time and Avatar offered him creative freedom and good money for an independent. When he was given the choice of who to work with among the already working Avatar artists, he picked Mike Wolfer and myself. Warren was already a big name by that point, and he helped steer the company toward the "Dark Vertigo" direction they became for a while, which led to a bunch of the best writers in the medium setting up titles there.

Did you know who Ellis was before you started working together?

I had read something short that was in Heavy Metal. I was aware of Transmet but I hadn't read it yet. I was very much the poor Art School kid and only had limited access to comics in the late 90s.

Dark Blue was being serialized in Threshold. At what point did you and Ellis start talking about doing something else?

We didn't really ever talk. A few short emails, a little interaction at the WEF [Warren Ellis Forum], but we didn't collaborate in the traditional sense. He set up everything through Avatar and William acted as the go-between for everything. I was essentially an Avatar employee at that point. Warren was happy enough with the work that he continued to attach me to projects and I was happy to be working on this kind of content so it worked well for everyone.

You two worked together on a few things after Dark Blue like From the Desk of Warren Ellis and Bad World before you did Scars together. Was that project something that he wrote for you or with you in mind?

I don't honestly know. At that point he was writing a lot of shorter stand-alone stories for a bunch of publishers and it was just assumed that if it was for Avatar, odds are it would be Wolfer or myself on art chores, but Mike was focused on the Gravel stuff. For all I know, Scars may have been pitched to Vertigo first. But that's just speculation. He may very well have had me in mind specifically.

You were working for Avatar for a long time. How long were you under contract for them?

I think it ended up being about 18 years. Quite a long time, and there were a lot of reasons for that. I was definitely not capable of producing mainstream quality work initially. I had a lot of bugs to work out and Avatar was happy to keep me employed, doing what I love. And they actually paid me when they said they would, which was not something I was used to with indie publishers. I was very comfortable in the black & white small press world of that time. It wasn't always the content I wanted to work on, but that changed early on. From there it was as good a working relationship as one can have. There was never a gap in interesting projects with top tier writers and they continued to raise my page rate every contract until I was making rates as good and sometimes better than Marvel or DC offer. I even got health insurance for a time, which was unheard of for freelancers in American comics, especially indie comics.

Did you have much interaction with writers or choosing projects, or were you – and them – mostly going through William?

Initially, I had pretty much no contact with the writers. It all went through William. I'd get offered a story, sometimes I'd even get to pick among a couple of interesting things, and then I'd get full scripts. There was no need for much communication. And I really wanted to be respectful and professional. I knew I was working with A-list writers long before I could bring A-list skills to the table. But you work with the same people a few times, you start to get comfortable and more interactive. But it took a while to not fanboy out around Garth. And with Alan, forget it. I visited twice and both times it was like meeting the Beatles!

After a few projects with Ellis, you made a few projects with Garth Ennis. And you guys have worked together more recently, but you two clearly work well together. What is it about how the two of you work that complements each other?

After a few projects with Ellis, you made a few projects with Garth Ennis. And you guys have worked together more recently, but you two clearly work well together. What is it about how the two of you work that complements each other?

I think a big piece of the puzzle is Steve Dillon. I was a big fan from reading Preacher. I think I developed a lot of my storytelling shorthand reading his work and a handful of others from that first wave of Brits who did Vertigo work in the 90's. I think having at least a similar approach to paneling, composition, pacing, and acting made it easy to know what was expected and that made both of us comfortable. I had an insight into how his stories flow, thanks to Steve's work so things always flowed well and made sense to me. But also, the stories we've done have always had an unpredictable mix of horror, humor, and grit that is exactly what I wanted to draw. I always have a great time drawing Ennis books.

I was going to ask about Steve Dillon because he is one of the artists you’ve often been compared to, both in terms of style but also the ways you’re both very at these almost understated quiet moments and then these scenes of action and horror. How much was that intentional? How much were you trying for this very realistic approach in a lot of ways, that would really propel and increase the impact when the tone changed?

I was always aware of my limits as an artist. I knew that a lot of things were going to gradually improve as I did more and more pages, but storytelling was where I could be confident. None of the books that I loved and connected to on an emotional level were drawn big and flashy with their storytelling. Those hyper dynamic splash pages and crazy layered panel pages you'd see from the Image guys were great, but they didn't move me the way the more experimental parts of Frank Miller in the '80s or things like Akira did. So I focused really hard on learning clear and clean paneling that could be read by anyone. I think Dave Gibbons may have been the first artist I read where I noticed the power of character acting but then that became another major focus. Dillon was just great at all of that stuff so he became an instant favorite.

Antony Johnston adapted The Courtyard among other Alan Moore projects at Avatar. At the time, did you have any idea that doing that comic would essentially define and shape your career for years to come? Or was it just another project?

I certainly had no idea we'd ever revisit that world. I was very excited to draw the Courtyard as soon as I heard about it. I figured it was the closest I'd ever get to doing an Alan Moore book, even if it was an adaptation of a short story, Alan was still heavily involved. In fact, it was his idea to do the whole thing in that format, with two vertical panels per page. I loved that. It turned it into more of an illustrated story than a typical comic and it challenged me to think about composition in new ways. I learned a lot from doing that book. But Neonomicon was a total surprise when I heard we were doing it.

Before you started working on these books, how well or how much did you know about H.P. Lovecraft and his work?

Before you started working on these books, how well or how much did you know about H.P. Lovecraft and his work?

I had gone through a small Lovecraft phase in high school, reading a handful of the better-known stories, but my knowledge wasn't deep. Between The Courtyard and Neonomicon, I picked up a collection that had everything he had written and read that cover to cover. I would never consider myself an expert, but I was at least familiar with everything by the time Neonomicon rolled around. I didn't know a tremendous amount about Lovecraft himself until we did Providence. There was stuff I'd stumbled across during research and stuff I learned from Alan. As you know, he writes massive scripts with a lot of extra information for context and he'd often pull stuff from some of the many research books he'd read and put it in the script so I could be fully informed about why we were taking things in certain directions during the production. It was quite helpful and rare, honestly, to have that much insight. The deeper thinking behind the scripted actions instead of just stage directions, you know? A lot of people find those Moore scripts challenging because of the density but I really liked it, even if it was a ton of work to get it all on the page.

One reason I ask is that Lovecraft always liked to talk about unspeakable and indescribable horror. Which isn’t easy to draw, or suggest.

On one hand, I get that what you don't show is often the scariest thing. You hear that a lot. But I think sometimes you can visually show something that isn't truly describable. For example, the monster from Carpenter's The Thing or the Tetsuo monster from the end of Akira. I would have a hard time describing those but I can see them clearly in my memory. My stylistic approach has always been to show things in clear detail as part of the clean line style I like to use. So in order to do that with things that would normally be hidden in shadows or be drawn with a loose, undetailed style, I relied on odd textures from nature, or, thanks to the brilliance of the scripts, we'd put in small optical illusions to unsettle the reader and make things feel off. You have to find a way to make something mysterious while in plain sight. There was a temptation to get more illustratively experimental in kind of a Sienkiewicz way in some of the weirder parts of Providence but A, that would've been out of my wheelhouse and probably wouldn't have turned out as good as I'd like. And B, I wanted to maintain a consistent visual language for the series, even when reality was breaking.

As far as Lovecraft, the creature in Neonomicon – a fabulous monster, by the way – is not the creepiest or most disturbing element of the story. Which I think is one of the things you were talking about. Capturing that Lovecraftian feeling is about tone and style and a lot of these artistic choices you were making. And playing it so “straight” in your style, made it more horrifying.

As far as Lovecraft, the creature in Neonomicon – a fabulous monster, by the way – is not the creepiest or most disturbing element of the story. Which I think is one of the things you were talking about. Capturing that Lovecraftian feeling is about tone and style and a lot of these artistic choices you were making. And playing it so “straight” in your style, made it more horrifying.

He was a lot of fun to design. We've all seen our share of fish-man monsters in various media and I wanted him to have his own look. My early versions were very much the classic man-in-a-rubber-suit Black Lagoon Monster, but Michael Phelps was a big deal around then and it got me thinking about the ideal swimmer's physique. We bulked up the lung capacity, added fins, gills, webbing. Then, when I saw pictures of some of those deep sea anglerfishes, I loved that head shape. Humanoid but still very alien. And a creepy fishman was born.

Going from Crossed to Neonomicon, it was two very different approaches to horror, which you drew roughly back to back, I think.

That wasn't particularly difficult for me. Horror is my default setting, generally speaking. Even when I'm working on something like Punisher or Moon Knight, I'm still visualizing it as horror. When the violence happens, it is going to be brutal and shocking because I want it to be disturbing, not cartoony and consequence-free. So while they were different subgenres within horror, I'm very comfortable in both. Moving from psychological thriller-turned-horror to apocalyptic survival-horror never felt like a big jump. One of the major influences for Crossed was The Road by McCarthy, which played with the post-apocalyptic genre in an ethereal, nightmarish way that I think makes it at least a cousin to the surreal, unspeakable elements of Lovecraftian horror. Just two sides of the multifaceted dodecahedron that is horror.

Moore’s scripts are famously dense, as you said, but the ones I’ve seen, he’s talking to the artist and trying to give you all the information he had and needed, and it sounds like you enjoyed that. I would imagine that Providence required you to change your process a little. If only because of the research involved.

Moore’s scripts are famously dense, as you said, but the ones I’ve seen, he’s talking to the artist and trying to give you all the information he had and needed, and it sounds like you enjoyed that. I would imagine that Providence required you to change your process a little. If only because of the research involved.

Research became very important. Not only did it add the necessary authenticity to the period and setting, but it made me more comfortable. I felt like, if nothing else, I'll get this part right! When we did The Courtyard, I certainly never expected to come back to that world. It was just two issues and I did no research but as we expanded and explored real places, it became important to try to capture more of a sense of the places. I wanted Red Hook to look like Red Hook and it bugged me that none of the locations I'd made up for The Courtyard felt authentic. With Neonomicon we bounced around a little but the more I researched the real places and saw real-world buildings and nature that I could place into the book, the more it felt legitimate. So with Providence, I'd do deep dives on every element that seemed like it could be researched. Mostly over the internet, but I also bought stacks of old books about different towns, fashion pattern books, folk art, construction, culture, everything. The visual research was extensive! I had folders 300 images deep for a municipal building you'd see in the background of 2 pages. But this ended up feeling like it was just as much a part of the work as the drawing. I really loved it because you'd sometimes find a thing that was even new to Alan and he'd be ecstatic about that new layer.

What was the oddest or most surprising thing you uncovered while working on Providence? Because I’m flipping through the books and there’s so much detail as far as the architecture, the clothing, the wallpaper, a hundred different things that I’m sure a lot of readers never notice. What did you enjoy learning about or figuring out in making the book?

If a visual reference could be found, I would find it. And I wasn’t alone on this. I believe Avatar even had a paid researcher or two early on, if I am remembering correctly. While researching fashion and the nightlife of New York City in 1919, I kept coming across mentions of the great golden age illustrator J.C. Leyendecker. He was sort of the Norman Rockwell of his time and one of the key figures in defining the look of that era's advertising art. His life actually had many parallels to our main protagonist, so I ended up trying to make Robert look a lot like a Leyendecker illustration, design wise, as an homage from one artist of today to another of the period the book is set in. One more unspoken bridge from the past to the present. It was definitely a bit obsessive but that was what Providence needed to be.

How much did you know the end of Providence, in detail or just in broad strokes? Do you generally want to know the plots you work on?

Alan had most of it planned out well in advance and I was aware of where it was going, but I didn't know any specifics until the scripts started coming in. I think if too much of it is spelled out for me in advance I'd lose some of the fun of discovery during the script reads. Garth generally doesn't tell much about where things are going. He's not keeping secrets, I can ask questions and sometimes the script alludes to things we'll need to know in future issues, but it's really fun to get a script and not know what is going to happen. Maybe that translates to some excitement on the page when you draw it.

After Providence, which was a huge deal, which was your best work to date, what do you decide to do next? How do you decide what to do next?

Providence was really exhausting. Finishing it felt like finishing college. I just felt like I needed to try something new after doing indie stuff for the better part of two decades. Avatar's business model seemed to be changing at that time too, moving to doing fewer monthly titles and more Kickstarters. It just felt like it was time. I kind of wanted to see how my work would change and evolve once I was working in a different arena. I was also just curious about life at the big two, to be honest. The kid in me really wanted to know what it would be like to be a Marvel Comics artist. I knew Axel Alonso when he was at Vertigo. We never worked together but we would chat at cons every now and then. He was the one that got me work at Marvel that led to the Moon Knight series I drew with Max Bemis. I believe he had also started laying the foundation of the Punisher: Soviet project when he split with Marvel. But I'm really grateful for him because Soviet, specifically, was a bucket list project for me. Getting to do a Punisher Max project with Garth, and getting to be a part of that line of books that are among my all-time favorite comics, meant a lot to me.

So tell me about Punisher: Soviet. Was this something that you and Ennis were developing together? Did he write this with you in mind? Were you two able to get back into the groove you worked in before, or was this different?

Garth knew I was attached to the project but it was his show. He does his research and writes the whole thing, then sends out full scripts. That's how we've always worked. I've always seen my job as trying to get as close to the writer's vision presented in the script as possible. I can see the appeal of more collaborative development but when you have writers who you trust to nail it, it is best to stay out of their way and let them tell the story they want. I did have some issues during this production but it had nothing to do with our working relationship. That was as comfortable as always. There were two home moves – one halfway across the country – a house purchase, and some minor medical stuff, all very distracting. I had a lot of trouble getting things done quickly, but Marvel was very hands-off on this book. They were fine letting the book come together at its own pace and didn't start trying to speed me up until we were close to the end. It was frustrating at times because I'd work for eight hours and then hate everything I'd gotten done. I think I was dealing with some burn out and I put a lot of pressure on myself. It can be frustrating when you are working really hard to be better but you aren’t seeing it on the page. I think all comic people go through stuff like this, but there are bills to pay. You keep producing and eventually find your way back to a good workflow. Which is also when you find yourself making pages you are happier about. Overall, I’m happy with how Punisher: Soviet turned out but I felt like it was a fight the whole way.

There are kinetic aspects of the book like the car chase and some of the action scenes, which can be hard to stage, and you do really well. I’m curious what did Ennis give you and how do you go about figuring that out.

It came down to trying to figure out a consistent approach to action that felt right. There were certainly much more dynamic ways to do all of it, from the chases and shootouts to the helicopter stuff. But I wanted things to feel cinematic and grounded so I kept a handle on the cartooning exaggerations and speed lines and tried to capture movement in other ways. It does flatten things out a bit and makes some stuff look stiff, a criticism I've always gotten, but I think if there is a consistency to it, the world feels more tangible and grounded in realism. At least to me. Choreographing the chase was interesting. It really came down to doing a ton of sketchy storyboards based on how I thought it would play out on Google street view, and then picking and choosing interesting shots. Sometimes I do think it would be fun to go wildly cartoonish and dynamic but the project has to call for it, and even when I do sketches, I find it hard to break the habit. I spent so long moving towards this version of realism, that it can be hard to remember that in art, there are no rules.

Do you prefer inking yourself?

I do like having control over the final image. You sometimes get into a good groove with the materials and you make some changes on the fly that improve everything or find just the right textures to bring a background to life. But sometimes I find switching back and forth between pencils and inks can be jarring. Penciling is a different set of problems to solve and it can sometimes take a while to warm up those muscles after being in an inking mindset. At least for me.

How have you found working on superheroes and working at Marvel? You seem to like what you’ve worked on. Have you been thinking about what you want to do more of or try next?

I really like the challenge of different genres. I've always wanted to see what sort of approaches and imagery I could come up with doing vastly different things. Warhammer definitely scratches an itch to do brutal military sci-fi, but I still want to do fantasy, and a more surreal, Moebius-type of sci-fi. Superheroes can give you access to a lot of crazy options but, oddly enough, all of my Marvel stuff has been pretty grounded in street level heroes. I really want to push the limits of my imagination and see what crawls out instead of just doing your version of things that have been done a hundred times before. I suspect that in order to do that, I'll have to make a move to the creator-owned world at some point, assuming I could find a way to make a go of it. Honestly, I still feel fairly unknown in the broader comic world. I don't do many conventions and I don't put any real effort into social media so I'm kind of invisible compared to a lot of my contemporaries, which is probably not the best way to have a modern career. But I'd really rather people focus on the work. But can someone successfully do creator owned work without building that cult of personality? I'm not sure. I've been a freelancer my entire career, I just think it would be pretty awesome to get to make up my own stuff!

Marvel did announce your next big project. How did you and Kieron Gillen end up making a Warhammer 40,000 comic?

I saw the initial announcement of the Marvel/Games Workshop collaboration online like everyone else. At that early stage, there were no specifics available. I was already a fan of the Warhammer 40K and Warhammer Fantasy universes, mostly through video games but I also follow a lot of pro and hobby modelers just as art inspiration. The stuff these people can do blows my mind. So I was familiar with the aesthetic and I thought it would be a lot of fun to work on that stuff. I figured at the very least I might be able to get a cover or pinup job so I wrote to Rickey Purdin and told him to throw my name in when it came time to discuss the book. When I heard back from them and found out Kieron was writing it, I got really excited. I knew from his blog he was an avid player with a handle on the deep lore of the 40K universe and I had wanted to work with him going back to the Avatar days but the timing had never worked out. I started right after Punisher: Soviet ended. And that's when Covid started. I suppose it is very appropriate to be drawing a Warhammer project in Grimdark times.