There’s a scene in a recent movie about Ruth Bader Ginsburg that stuck in my head after I saw it. It’s in the biopic On the Basis of Sex, when the future justice and some of her Harvard Law classmates are gathered at Dean Erwin Griswold’s house for dinner. The year is 1956, just six years after the law school started admitting women. In that scene, the dean asks each of the women in the class—nine of them, including Ginsburg—to stand up and explain why she’s at Harvard, taking the place of a man.

This really did happen, and it’s a story that’s been retold countless times over the years, including by Justice Ginsburg herself (On the Basis of Sex was written by Ginsburg’s nephew, whom I’ve interviewed). The story itself has thus taken on a life of its own, in part thanks to the way Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s astonishing legal career has made it seem in retrospect even more absurd. That night at Dean Griswold’s has become yet another part of the hagiography that surrounds the Supreme Court justice. In the movie, of course, the spotlight is on Justice Ginsburg, as she drily replies that she is at Harvard because she wants to learn more about her husband’s work. But when I watched that scene, I thought: What about those other women, giggling in the background at Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s response? Those women, pioneers all, are now just extras in movie scenes about their famous classmate. But who are they? What drew them to join a class of 500-plus men to study the law, and what did they hope to do with their degrees?

Beyond that, I was determined to know what became of them at Harvard, and beyond. Did they band together amid the sea of men, supporting one another in the face of occasionally hostile professors, and later, hostile workplaces? Did they marry the loves of their lives, as Justice Ginsburg did, and find fulfilling work in the law? Did they spend their careers cheering on their petite classmate from afar, as she shattered glass ceilings and built a constitutional system that protected gender equality? Or did they secretly believe that but for a twist of fate here and there, they too could have been seated at the highest court in the land?

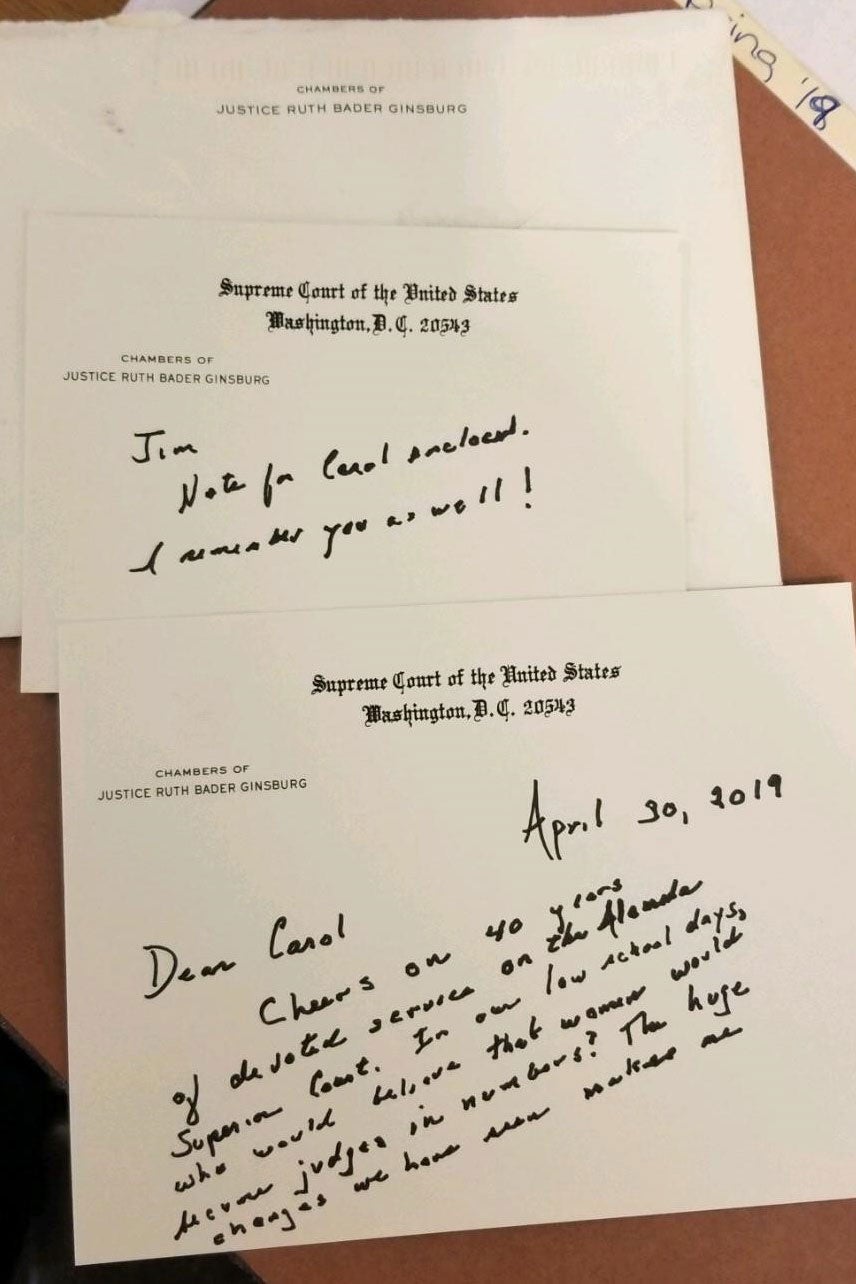

Well, it took more than a year, but we found them. Of those who survive, we took oral histories and turned some of those interviews into a two-episode podcast series. Of those who do not, we spoke to their family members in order to try to assemble a complete picture of the divergent paths of that class of 1959. We collected photos and notes and stories to try to build an archive of these women’s lives and careers. We even tracked down one woman we had missed at first, because she had dropped out of Harvard Law and wasn’t in the yearbook—we found her only because Justice Ginsburg herself told us that we’d gotten the number of women in her class wrong, as one of her female classmates had dropped out before graduating. (What we learned when we tracked her down is that this classmate eventually went back to get her law degree and became so involved in advocacy work that she’s been arrested for protesting in her 80s.)

We gathered their reflections on hazing at Harvard, professional setbacks and frustrations, relationships and child rearing, and the progress of the feminist legal movement. We found that while these women did keep tabs on one another, and sometimes cheered one another on from afar, they were mostly very busy, consumed by their own careers and families and goals. Instead of a tale of easy camaraderie, we learned that the extraordinary pressures on these women didn’t always create a sisterhood. Sometimes, the pressures even drove them apart.

As tempting as it is to be drawn to the drama of small rivalries, or to look for simple narratives about the women of Harvard Law School’s class of ’59, that’s never felt like the point. It’s always been clear to me that this story wasn’t a fun little League of Their Own set at the Ivies. But as we worked on this project, the easy conclusions—for instance, that having a Marty Ginsburg was the obvious difference between becoming a Ruth Bader Ginsburg and becoming a Rhoda Solin Isselbacher or an Alice Vogel Stroh—started to feel more and more incomplete. Because after I reread the biographies of RBG’s classmates, I went back and reread some of her most famous opinions and dissents. And there they were. The class of ’59. The story of Carol Brosnahan and absurd pay discrimination peeks through Ginsburg’s dissent in the Lilly Ledbetter fair pay case in 2007. The stories of Rhoda or Alice’s career-dampening pregnancies or pregnancy losses are simmering under the surface of her 2014 dissent in Hobby Lobby, where she writes about the burdens of inaccessible contraceptive care. The slights and stings of the discrimination each of these women faced in job interviews, promotions, and fair pay form the spine of her dissent in the 2011 class-action discrimination case that was Wal-Mart v. Dukes. And the story of all these women and that infamous dinner party at Dean Griswold’s house is suddenly the subtext of her historic majority opinion in the Virginia Military Institute case that desegregated an august all-male military institution in 1996.

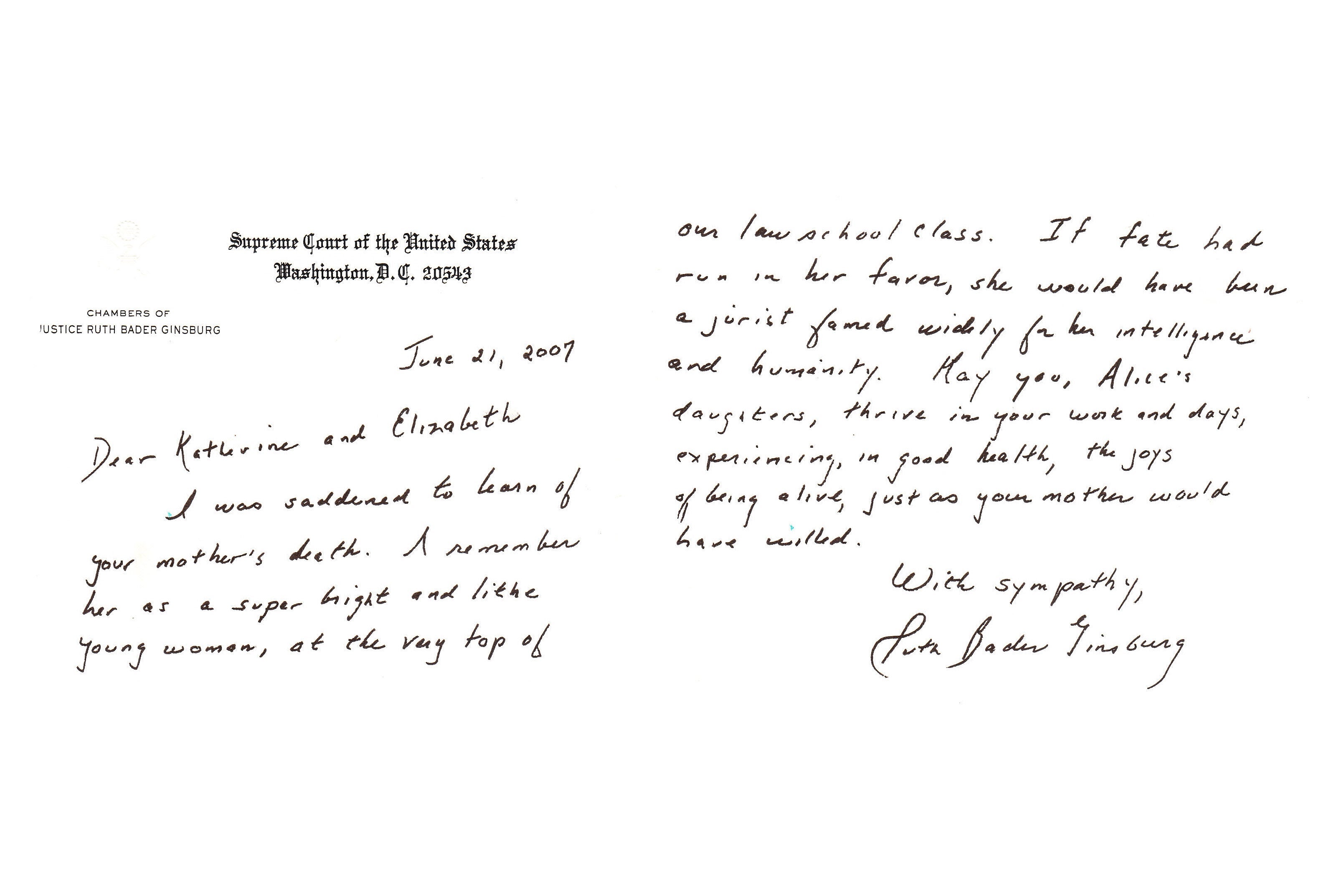

When one of her classmates, Alice Vogel Stroh, passed away in 2007, Justice Ginsburg wrote a letter to Alice’s daughters, telling them that it was a matter of luck or fate that their mother had not become a great jurist herself. Ginsburg wrote that she hoped Alice’s daughters would thrive, in their lives and careers. And in her own five-decade career, Justice Ginsburg has worked to ensure that the life experiences of the class of 1959 would not be replicated for Alice’s daughters, or for anyone else’s. The barriers and attitudes that kept some of her classmates from having careers as large as Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s are not a matter of luck or of fate, or even of marrying the right guy. Those barriers are built into the very systems that treated Ginsburg and her classmates as inconvenient, or less-than, or odd. In a sense, then, RBG’s lifetime work is an aggregated living monument to her classmates: their struggles, their victories, and their legacies. Their stories are written right into the doctrine, as the fight continues to build equality into the Constitution and the justice system—to which each of these women, in different ways and to varying degrees, dedicated their lives. —Dahlia Lithwick

Read Slate’s full interview with Ruth Bader Ginsburg about her own time at Harvard Law School and her memories of her female classmates here.

Carol Brosnahan, born 1934

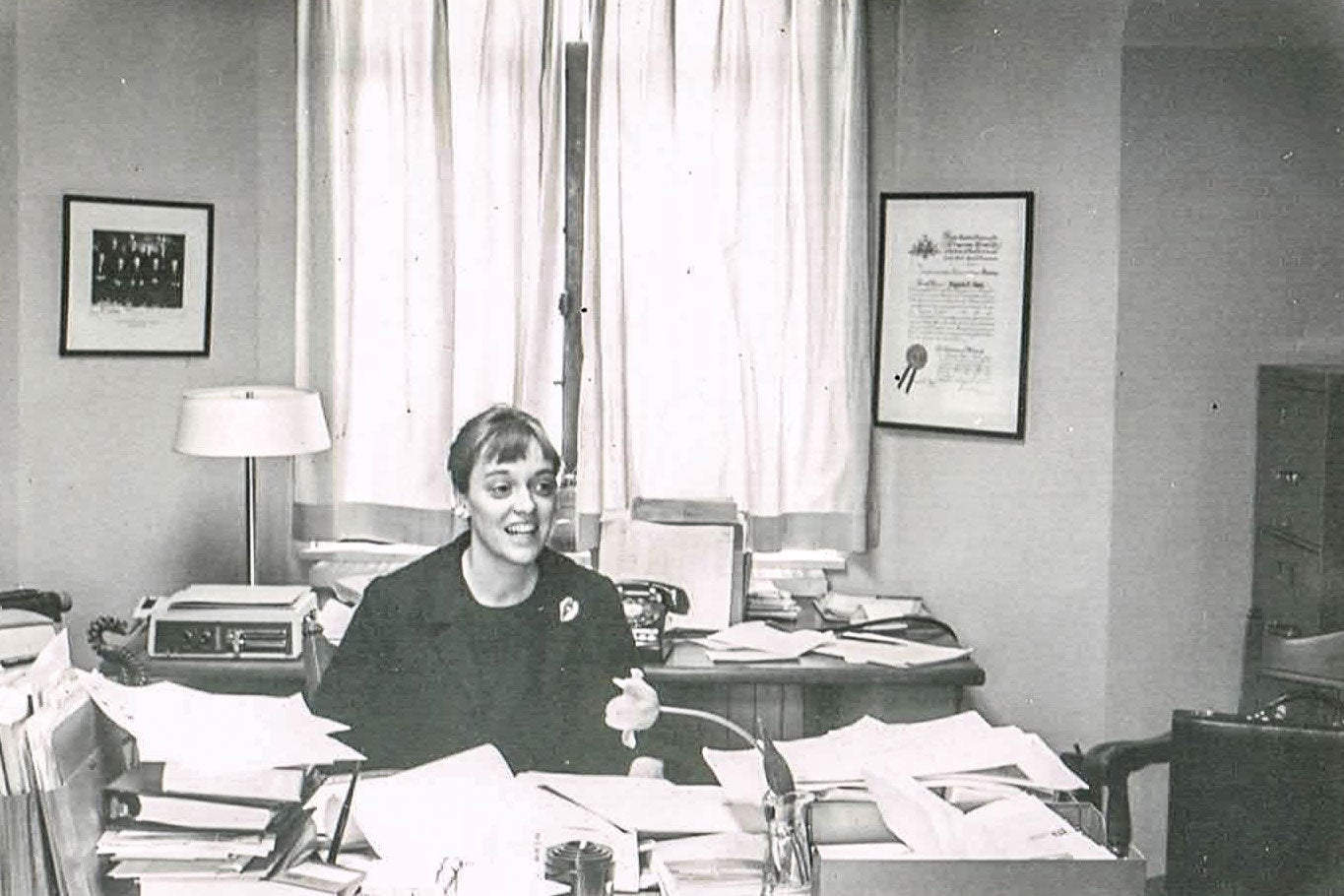

When she was a midcareer lawyer, Carol Brosnahan knew she was doing as much or more work than the two men above her. But when she asked to be promoted to their level, she was refused. “So I said, ‘The heck with it, I’ll put my name in [for a judgeship] and see what happens,’ ” she said. Last year, Carol celebrated 40 years on the bench.

“Women weren’t supposed to be managing the money”

Carol Brosnahan, born Carol Simon, grew up in Queens, New York. She was a bookish, shy kid for whom schoolwork came easy. She was accepted into Wellesley, where she studied economics. Then she took a job on Wall Street, researching investments for wealthy clients. “I wasn’t allowed to meet the clients, because women weren’t supposed to be managing their money,” she recalled.

She stayed at the job for a year, during which she got engaged. “My fiancé said it wouldn’t be appropriate for me to work, but I could go to school,” she said, which is how she began an application to Harvard Law School. But it wasn’t until she broke off her engagement that she decided to go through with it. She called the school’s dean a month and a half before the start of the semester. He looked at her grades and test scores, and told her she could enroll.

Hostile professors, hungry men

For Carol, who had attended a women’s college, there was something fun about landing in such a male-dominated environment. “There were nine women and 525 men in the class—I would never have had to take a note if I didn’t want to,” she said. She met her husband thanks to his domestic haplessness: She offered to make dinners for a house of six men—including her future husband, Jim—in exchange for free food.

But while she got along well with many of her male classmates, her professors often singled her out in humiliating ways. She recalled the night when Dean Erwin Griswold asked the women why they were there in law school, taking the place of a man. In her memory, she was too shocked to respond. “The fact that the dean said that was less of a problem than some of the professors who really didn’t want women in the class,” she said. “Some of the professors were supportive. But others were really hostile.” Read Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s memory of the dinner with Griswold.

She became close with her roommates, Flora Schnall and Betty Jean Oestreich. But while she was familiar with the other women (familiarity was “sort of a necessary thing because there was only one woman’s restroom”), she never felt they were a cohesive group. “We were all oddities, of one sort or another,” she said. “You would walk in and everybody would look. Because we’re this weird group of people, you know, with breasts.”

“The phrase gender bias didn’t exist”

Newlywed, Carol and Jim raced out of Cambridge as soon as their exams were over, eager to start a new life where nobody knew them. “I’m Jewish, and he’s a fallen away Catholic, and that was not acceptable, really, in 1959,” she said. She and Jim had read in a book that Phoenix was “all Democrats,” and they were ready for warmer weather anyway. Jim found a job with a plaintiff’s personal injury firm, but Carol struggled to find anything in her field. Eventually, she took a clerical job. She also worked on the John F. Kennedy campaign part time, until she was booted from the job just a week before giving birth to her first child because the campaign didn’t have the insurance to cover her.

By the fall of 1960, Carol had stopped working altogether. She had three children in under four years. Between the second and third pregnancies, the family moved to the Bay Area for Jim’s job with the U.S. attorney’s office there. When her youngest daughter was still an infant, Carol took the California bar exam—her second certification, after Arizona—as she began to feel she was “going crazy” staying at home. So she took a job with the Continuing Education of the Bar, which provides training and publishes books for practicing lawyers. She began editing and writing books on the law, focused on poverty, bankruptcy, and tenant law. Jim was supportive, but “my husband didn’t change diapers,” she said. “He was a great dad, but the household and the children were my responsibility. It was a lot of juggling and not very much sleep.”

Even as she moved up in the agency, she found that her career growth was limited. “This was a time when the phrase gender bias didn’t exist, except gender bias existed,” she said. Though she had been at CEB more than a decade, she said the director refused to give her the same title as her male colleagues. “And that’s what got me to put my name in for a judge—gender bias.” Eventually, she got a call from a man in Gov. Jerry Brown’s office to inform her she would be appointed to the Berkeley municipal court. “And tell Jim you got this one on your own,” the man said.

Carol still considers herself to be in the most rewarding part of her career. In Berkeley, she helped launch a drug court around 1999, which she ran until she was moved to Oakland to serve on the Alameda County Superior Court. She approached the district attorney around 2009 about forming a behavioral health court to help people living with addiction. Two days a week, she conducts legal proceedings at a courthouse in a psych ward. “I’m trying to keep [people] out of jail,” she said. “To see the families that have been reunited because of what we’ve accomplished in these courts—that’s wonderful.”

“I’m not giving up”

Carol said that over the course of her career, she’s gone from often being the only woman in the courtroom to sometimes presiding over a courtroom of all female attorneys. Still, she doesn’t think women have it easy working in law these days. “The feeling that somehow it’s not feminine to fight for your client,” she said. “The feeling in some areas that the appropriate job for a woman is family law. There are still biases.”

Even if the older generation was “not receptive completely to the idea of a woman” working in the law, she feels she mostly outlasted them. “I’m 84 years old and still working,” she told Slate last year. Carol plans to retire next month, at age 85, but she says she’ll return to the bench, on occasion, on assignment. “I’m not giving up completely,” she said.

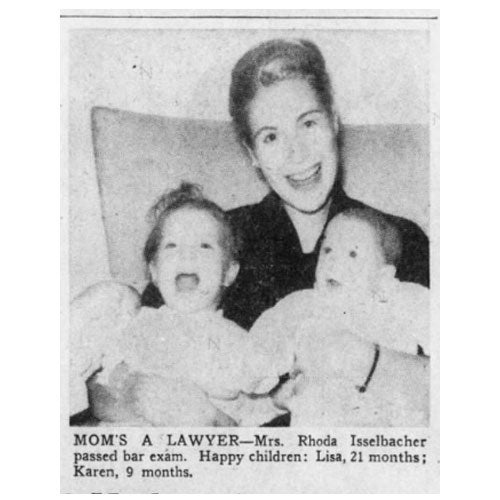

Rhoda Solin Isselbacher, 1932–2015

When Rhoda Solin Isselbacher found out that Ruth Bader Ginsburg had made it to the Supreme Court, she cried. And not out of joy. The two women had attended Cornell together as undergrads. They were the only two young mothers in their class at Harvard Law School. And yet, despite these parallels, they never became close friends. According to Rhoda’s son Eric, the traits that made both women so successful—confidence, intelligence, determination—pitted them against each other. “They both were role models for women who wanted to be in a man’s world,” he said. “And yet the fact that they ended up being kind of rivals—I always felt really bad.”

“A tough exterior out of necessity”

Rhoda’s mother died when she was an infant, so she was raised by her father, Jay, a gruff grocery store owner and, eventually, a new stepmother. Jay let the rest of his family do much of the child rearing and, according to Rhoda’s daughter Kate, never made a secret of the fact that he’d wanted a son. Kate remembers her mother describing a difficult childhood. “She developed a tough exterior out of necessity.”

At Cornell, Rhoda studied philosophy and religion. But her love of debate prompted one of her professors to tell her she was “made” to be a lawyer.

In her second semester as a law student at Penn, Rhoda went to a wedding in D.C., where she met Kurt Isselbacher, a promising medical researcher. They both ditched their dates and danced the whole night. Two dates later, they agreed to get married. Rhoda transferred to George Washington University Law School so she could live with her new husband. The next year, when Kurt was offered a job in Boston, Rhoda transferred again, to Harvard.

Rhoda and Ruth had been “friends” at Cornell, Kate said—“but wary with one another.” Kurt recalled that Rhoda would often say how beautiful she thought Ruth was. (Kurt died a little over a year ago, a few months after he spoke to Slate.) Rhoda’s daughter Jody said she thought any rivalry was “always in good fun.” Kate, though, said her mother was likely thinking about real stakes. They both knew, Kate said, that when they graduated, they’d be competing for the same limited number of law school spots available to women. Justice Ginsburg did not have quite the same recollection of the relationship as Rhoda’s family. Read her memories of Rhoda here.

Pregnant at Harvard Law School

Her family thinks Rhoda entered Harvard Law as the school’s first-ever pregnant student. She once told an entire lecture hall that she couldn’t be expected to walk to another building to use the women’s restroom (the only one in the entire law school), and instead proposed that she could use the lecture hall’s men’s room, as long as she put a sign on the door. The men agreed. “I think she saw [the unequal treatment] as a challenge, but she’s somebody who felt like it was a challenge she was perfectly capable of tackling,” her son Eric said. Rhoda claimed to have never once stepped inside the law library, instead bringing her studies home at night while she cared for her infant—much like Ginsburg.

According to Kurt, Rhoda got the highest score in her sitting of the 1960 Massachusetts bar exam—and she had a fever that day. Still, it took a while for her to settle into a career. She did part-time work so she could take care of the children—four kids under age 6—and bounced around to small law firms, mostly focusing on estate law. She would later advise Jody, a lawyer too, to go into estate law for the work-life balance it offered: “[Mom would] say, ‘It’s death and dying, but it’s not like if they drop dead, you have to be in court the next day,’ ” Jody remembered.

Rhoda’s high standards could be intimidating. “She didn’t celebrate free time and frivolity,” Kate said. “It was, ‘You know what you have to do, so do it.’ ” The family spent summers in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, with Nobel Prize winners and college deans, Kate said. The children got a clear message: “In my family, you sort of had to be somebody,” Jody said.

“Fathers didn’t do that back then”

Rhoda had child rearing help—from nannies. In 1993, when Ginsburg was named to the bench, Jill Abramson wrote an article for the Wall Street Journal about how the careers of the other women in the class of 1959 were shaping up. Rhoda told Abramson the story of being pulled away from a client meeting to take one of her children to the hospital for a dog bite. “My husband’s a doctor, why isn’t he on his way to the children’s hospital?” she remembered thinking. “But fathers didn’t do that back then.”

Kurt attributed his own professional success to Rhoda’s canny strategizing. “She guided me through my career,” he told Slate. Their children remember it, too. “She was like his coach, his chief of staff, his confidante,” Eric said.

A pioneer in legal advocacy for patients

In the mid-’70s, Rhoda became in-house counsel at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, then known as the Sidney Farber Cancer Institute. (Rhoda negotiated the deal that led to the name change.) She had recently undergone two years of chemotherapy for breast cancer, and the job felt personal. At the time, biotech was giving rise to knotty legal and ethical questions about patient rights, clinical trials, and intellectual property. “It was a new area of law she spearheaded,” her son Eric remembered. She set up one of the very first patient advocacy programs in any hospital in the country.

After 10 years, Rhoda was forced to resign when Kurt became the founding director of the competing Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center. To avoid any conflict of interest, she returned full time to the small law firm where she’d spent most of her career, Epstein, Salloway, and Kaplan—which later became Epstein, King, and Isselbacher.

“She married a lawyer. You married a doctor.”

Even though Rhoda’s professional path had never aimed toward the federal bench, Kurt remembered her disappointment when they were driving home from Cape Cod and heard on the radio that Bill Clinton had nominated Ginsburg to the Supreme Court. Kurt reminded her that she had chosen a career path that allowed more time with her family. And her choice to marry him meant she was never going to get the kind of support Marty Ginsburg could give Ruth. “Look, Rhoda,” Kurt remembered telling her, “she married a lawyer. You married a doctor, and I think that’s a major difference.”

Virginia Davis Nordin, 1934–2018

At the age of 16, Virginia Davis wrote in her journal that she wanted to be a politician. “Other people have the urge to paint, write, or compose but I have the urge to reform,” she wrote in her journal. “As yet I have no definite crusade to follow but am prone to latch onto any one that’s handy.” Later in life, she would find her cause—challenging sexism in academia and in the workplace. “As a girl I thought I was born 50 years too late,” Virginia told a reporter for the Ann Arbor News in 1971. “I could have been a suffragette.”

A “classic overachiever”

Virginia grew up near Detroit, the only child of an architectural draftsman and an elementary school teacher. She was what her children, Kendra Nordin Beato and Dayton Nordin, called a “classic overachiever”—she got straight A’s, wrote feminist stories for the literary magazine, and was voted class politician.

She graduated from Principia College, a small Christian Science college in Illinois, with a major in government. Law had long been an interest: In 1948, when she was 13 or 14, she had written a family friend a letter asking what it was like to be a lawyer. He warned her that women were generally limited in the field and emphasized her need to “train in secretarial work,” but he didn’t advise her against trying. “You need not be too much disappointed,” he wrote. “Much of the best and most lucrative practice is open to women.”

Virginia always felt uncomfortable at Harvard Law—like an outsider, her children said. Kendra recalls asking her mother if it was hard to be one of just a few women there. “She said, ‘No, because I was often the only woman.’ ” She was also a Midwesterner, and not wealthy—she worked her way through school with odd jobs like nannying and reading to elderly women.

She did find a friend in Ruth Bader Ginsburg, though. The two women were in the same section in their 1L year, and her children remembered their mother saying that she’d gone on double dates with Ruth and Marty. When Marty Ginsburg was in the hospital with cancer the next year, Virginia visited him there, which was a comfort to Ruth. Read how Justice Ginsburg remembered her friendship with Virginia, whom she called Jinnie, here.

“You’d end up discussing your theories on birth control”

After graduating, Virginia found that potential employers were unwilling to take her seriously. She told the Journal in 1993 that in those early interviews, she was often asked if she had plans to get married or have children. “You’d end up discussing your theories on birth control and nothing about your credentials,” she said. She landed a job clerking for a federal judge in San Francisco and went on to work as in-house counsel to a New York shipping company—a job she loved but ended up quitting because, as she told the Journal, her boss sexually harassed her.

In 1964, Virginia moved to Boston to serve as legal counsel to the First Church of Christ, Scientist, the founding church of Christian Science. It was there she met Kenneth Nordin, a reporter at the Christian Science Monitor whom she married just three months later. The next step of Virginia’s career was dictated by Kenneth’s decision to move to Ann Arbor, Michigan, to get his Ph.D. in American studies at the University of Michigan. Virginia was unable to find steady legal work in Ann Arbor. So she shifted into a career in academia.

Often the breadwinner

Virginia had her children when she was in her late 30s, working for the University of Michigan. For both children, she took just three weeks off work, which she deemed to be “a reasonable time,” as she told an Ann Arbor News reporter in 1971. Kendra and Dayton’s perception of their mother was that she gave them space. “She wasn’t the best housekeeper, and she certainly wasn’t clucking over us with concern,” Kendra told Slate. Virginia and Kenneth (who separated amicably in 1988) had a fairly modern marriage, sharing the housework. Often, Virginia was the breadwinner in the family, supporting her husband through grad school and a later stint as a freelance journalist. “We didn’t grow up with the white picket fence, the happy homemaker, the traditional roles,” Dayton said.

“It seems that I’ve got to be constantly pounding on the door yelling, ‘Let the women in’ ”

In Ann Arbor, Virginia worked for a number of progressive causes, including advocating for gender equality at the University of Michigan. She then worked at the University of Wisconsin, where she directed an institute dedicated to preparing women for senior administrative jobs, and at Dartmouth College, where she served as an affirmative action administrator. “It seems that I’ve got to be constantly pounding on the door yelling, ‘Let the women in,’ ” she told the Christian Science Monitor in 1972, in an article that characterized her as “combative.” She also taught at the University of Michigan Law School, where, with the university’s first Black law professor, Harry T. Edwards, she wrote a textbook on higher education and the law that was published in 1979. Her daughter Kendra thought she was very proud of writing the book but also conceded that her mother had always felt pressure to live up to her Harvard degree. “Even though she led this incredibly pioneering life, I think she felt she fell short,” she said.

According to Kendra, her mother passed the bar exam in at least five states. In a newspaper clipping of women who passed the California bar, Virginia is pictured holding a makeup compact. “[A]s if to say, ‘Women lawyers are smart and feminine,’ ” Kendra wrote in an email.

Wiltrud F. Richter, born 1935

Trudy Richter was the only woman in the class of 1959 who decided to leave Harvard without obtaining a law degree. For her it was a stuffy, lonely, hostile place. But Trudy—a person so dedicated to social justice that she is still protesting in her mid-80s—loved the law academically. Twenty years after dropping out, she went back to law school, and became a lawyer in her 40s.

An emotionally distant upbringing

Trudy grew up in a strict but comfortably middle-class German household in Rahway, New Jersey. Her parents, immigrants raising American children during the anti-German fervor of World War II, were emotionally distant. English was Trudy’s second language, but she was cautioned not to speak German in public. She knew that one of her maternal uncles, who had Jewish ancestry, had been rescued from a concentration camp, while the other was killed by Nazis. Her parents didn’t discuss the tragedy they fled from, but Trudy still felt its influence. “It’s easy with that kind of family history to be alert to all kinds of discrimination happening in this country,” she told Slate.

A love of protesting

Her appetite for advocacy developed during her time at a Quaker boarding school in Pennsylvania. The summer before she started college, she and several other students were arrested for blocking the sidewalk while handing out leaflets protesting the Korean War. She spent the night in jail. Trudy’s willingness to protest has never diminished—over the years she says she’s “collected a small rap sheet.”

She studied political science at Swarthmore College, where she also got engaged, then realized she wasn’t ready to be married and broke off the engagement in her senior year. Instead, she pursued her interest in the law, which she believed to be “the most effective instrument to further human rights and social justice.” She had excellent test scores, so she applied. “It never occurred to me that I couldn’t go to law school,” she said. “It was only when I got there that I realized what I was up against.”

“It was like living on an island by yourself”

There were warning signs from the start. During the application process, she was interviewed by a man who cautioned her not to get married and drop out. “Harvard thought it was doing a groundbreaking thing by accepting us. That was made very clear,” she said.

When classes started, she found that no men would even greet her, except for a few fellow Swarthmore graduates and one professor. “Nobody else, literally,” she said. “It was like living on an island by yourself. … They didn’t want women.” Trudy doesn’t remember ever interacting with her fellow female students. She lived alone, sharing a hallway and bathroom with an architecture student. “We exchanged a few words every day,” she recalled. “And that exchange was very important to me because otherwise nobody was talking to me.” Even her professors ignored her, she felt.

Harvard “helped propel me to a very bad marriage”

At the end of her first year, she dropped out and got married to a man she met while waitressing over the summer. “[Harvard] helped propel me to a very bad marriage,” she said. “Because I suddenly quit doing what half my lifetime I had wanted to do.”

Trudy left law school in 1957. Three years later, she gave birth to her son, James. She still itched to pursue law but didn’t think it was compatible with motherhood. So instead she got a master’s in education and taught students with disabilities for several years before focusing fully on being a mother. “Women were teachers in those days,” she said. “Women were not lawyers.”

She remained a full-time parent until her two children were teenagers. It wasn’t until 1977, when Trudy was recently divorced, that she decided to go back to law school. “I had this miserable marriage and was feeling ineffective as a person, and I hadn’t lost my interest in law,” she said. So at the age of 42, she began her degree at the Northeastern University School of Law. Trudy loved her time there. She described the school as Harvard’s opposite, as a place with an emphasis on diversity and practical experience.

“A good legal imagination”

Her first job as a lawyer was with a legal services firm, working on its family law cases. She later opened her own practice for low-income clients—handling everything from family law matters to misdemeanor defense. She also represented minors needing approval for abortions, pro bono, and helped women fleeing domestic violence obtain court orders. But she wasn’t able to make enough to even cover malpractice insurance and had to close after a year.

She spent the next decade working for the Disability Rights Center of New Hampshire. While there, she filed an amicus brief with the New Hampshire Supreme Court in defense of a man who was convicted of a crime for having sex with a mentally disabled person under what she believed to be a discriminatory statute. The court agreed with Trudy and ruled that a person with a disability who is genuinely able to consent to sex can do so. Another time, she resolved a case involving two deaf parents and helped spare them from losing custody of their children. “I don’t think anyone would account for my life in terms of major legal successes because of the kinds of clients I had, and the kinds of issues we had,” she said. But she took pride in her “good legal imagination.”

“The things I’ve done that I’m proudest of have not necessarily always been part of my work as a lawyer”

When James was still young, Trudy enjoyed volunteering during summers at a community playground, looking after children while their parents worked, and she also served as an elected representative for her precinct. “I’m sort of a born local government person,” she told Slate.

Her list of championed causes grew long over the decades. She campaigned to end the death penalty in New Hampshire, pushed to have her Unitarian Universalist church convert to solar power, and lobbied for legislative relief to undocumented immigrants. For five years, she supported a family from Bhutan as they transitioned to American life and used her legal training to draft a manual for other volunteers to do the same. The manual remains the one relied on by the church for its refugee program today. In 2018, at age 83, Trudy was arrested for participating in a die-in with the Poor People’s Campaign in New Hampshire. “Overall, it seems to me that the things I’ve done that I’m proudest of have not necessarily always been part of my work as a lawyer,” she said.

“A sole parent and homemaker”

Work-life balance was hard for her. Her husband, John, was an alcoholic. There were often periods when he ignored her and the children. “I was a sole parent and homemaker,” she said. Even when her children were older, she felt she was stuck in “survival” mode, focusing all her energy on meals and transportation and other logistics and very little on “sitting on the floor and playing with them.” She fears she modeled some of the behavior of her own highly “undemonstrative” parents.

A new lens on her law school years

Trudy couldn’t quite pinpoint when she began to think of her Harvard experience as something more than her own failure. She didn’t consider herself a feminist back in 1959—she doesn’t think anyone did. But over the years, she’s come to think of that experience in feminist terms, she said, and she recognizes that the hardships she faced in law school were not just personal.

In some ways, she felt her late start helped her escape misogyny in her career. But she says she still had a “pig” of a boss at the disability rights center, who would make cutting comments directed at the women and crude jokes at staff meetings. Her advice for female lawyers is something she wishes she’d done more herself: Find other women to talk to. “There’s still an alliance by gender,” she said. “It’s clear that women do need to help themselves find their footing.”

Marilyn G. Rose, 1934–2011

Marilyn Rose grew up in Massachusetts, the daughter of a Jewish cab driver and a factory worker who always pushed her, and her brother, to excel. “She had a real passion for serving the underprivileged,” her stepson Tim Childers said. “It was so much a part of her nature.” As a lawyer, she successfully argued a case that redefined how low-income people and people of color across the country could access health care, and its logic undergirds the entire health care law reform movement.

“She used to joke, ‘I’m the lowest paid lawyer to ever graduate from Harvard’ ”

Marilyn’s interest in politics pushed her toward law school, Marilyn’s sister-in-law, Rose Rose, said. Marilyn’s husband, Bobby Childers, said that Marilyn decided in high school that she wanted to be a civil rights attorney because of her own keen understanding of discrimination against Jews. Marilyn graduated in the top two of her class at Brandeis and decided to pay her own way through Harvard Law School even though she didn’t think she’d end up having a lucrative career, given her interests. “She used to joke, ‘I’m the lowest paid lawyer to ever graduate from Harvard,’ ” Teresa Peterson, her stepdaughter, said.

Marilyn never complained to her husband or stepchildren about her experience at Harvard. If anything, Tim and Teresa recall, she seemed to have thrived there. But it was also one of the first places she started advocating for systemic change—in her second year, she was denied membership in Harvard’s all-male public defenders program because women could not be sent to jails to interview male defendants. So she and fellow classmate Eleanor Voss publicly lobbied to have women allowed into the program, arguing that even without access to jails, they could still do plenty of work. Marilyn didn’t end up benefiting from her crusade, but the program opened up to women the year she graduated. Read Justice Ginsburg’s recollection of the efforts of women like Marilyn to improve things at Harvard.

A legal crusader for equality in access to health care

According to her husband, Bobby, Marilyn graduated with honors and then watched male classmates with worse grades land jobs at firms that had rejected her. Some companies openly admitted that they didn’t hire women. So she “had to go work for the government, the only place that offered her a job,” Bobby said. After a stint at the National Labor Relations Board, she transitioned to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (now the United States Department of Health and Human Services). She found a comfortable fit in the Office for Civil Rights, where she helped desegregate hospitals and mental institutions.

In her work overseeing health care at OCR, Marilyn learned about the Hill-Burton Act, a 1946 law that provided government funding to thousands of hospitals and clinics, as long as they provided some free care to patients who couldn’t afford treatment. She thought the act could be better enforced. By 1970, Marilyn had moved on to a nonprofit focused on providing health care–related legal help and signed on to represent eight poor Black patients in New Orleans who had been denied care from several hospitals. In Cook v. Ochsner Foundation Hospital, she argued that the Hill-Burton Act required that hospitals provide a certain amount of free care, particularly in emergency rooms, and that they accept Medicaid patients. The latter was a bold attack on segregation in health care: Southern hospitals were refusing the majority-Black Medicaid patients as a workaround to the Civil Rights Act.

According to Sidney Watson, a health law professor at Saint Louis University School of Law who worked with Marilyn, Marilyn was one of the first lawyers to fight for Medicaid acceptance as a matter of civil rights. “She began that conversation 50 years ago,” she said. “She just kept fighting the hard fight and calling out problems and coming up with creative ways of trying to address them.” After the judge ruled in Marilyn’s favor, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare created new regulations for enforcement. It was a major win for the burgeoning health care access legal movement. And it had a lasting effect: Though the Nixon administration rolled back some of her changes, “most hospitals still are expected to provide a certain proportion of uncompensated care to indigent and other uninsured people,” said David Smith, a public health professor at Drexel University.

A reluctance toward marriage

Marilyn first met Bobby Childers when they both worked for the Office for Civil Rights in 1964 (Bobby was tasked with integrating many of the South’s hospitals). Bobby’s first memory of Marilyn is from a meeting when he had announced his decision to allow Georgia to leave its psychiatric hospitals segregated out of what he considered to be the best interests of their more vulnerable patients. Marilyn didn’t agree with this reasoning—“she said I was a bigot,” Bobby recalled—and vowed to fight him on the issue. But the two became friends.

Some years later, after Bobby divorced his first wife, they started dating and got engaged. After the proposal, as Bobby remembers it, Marilyn cried for half a week. She had thought she’d never get married. But she was more afraid of losing Bobby than of marriage, and the two wed in 1978. Marilyn suddenly found herself stepmother to four teenagers. She jumped right in: “She attended school functions, helped Dad cook dinner, planned activities for us,” Tim said. Bobby still expresses awe over Marilyn’s generosity toward his children, particularly the youngest ones: “She was really the only mother the three kids ever had.”

“I’d never known any woman like her before”

Teresa says she took to her stepmom right away. She recalled an office party of Marilyn’s that she attended as a college student in the 1980s, where Teresa was surprised by the diversity of people and the fact that most attendees were smoking marijuana. “She was an anomaly at the time,” Teresa said. “I’d never known any woman like her before.” Marilyn’s approach to marriage surprised Bobby’s children: Marilyn and Bobby would often get into fiery political debates. “We thought they were fighting, but at the end of every conversation, they’d drop it and do something together, like cook or smooch on the couch,” Tim said.

Marilyn and Bobby moved to Florida, where Marilyn worked at a legal aid clinic and then as an administrative law judge. In 2004, Bobby and Marilyn traveled to D.C. for a celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act. No one there knew that he and Marilyn had married, Bobby recalled with delight. Both Bobby and Marilyn received plaques with an acknowledgment of their commitment to justice, naming them as “Civil Rights Champions.” Bobby and Marilyn remained devoted to each other until the end, Tim said: When Marilyn developed Alzheimer’s disease, Bobby took over her care until he was physically incapable, and then he visited her three times a day, for the last seven years of her life.

Flora Schnall

When asked her age, Flora told us: “You could say I’m over 80.”

After deciding she didn’t have the talent to pursue piano, Flora Schnall envisioned a career as a political journalist. But it was 1956, and she didn’t see many women gainfully employed as reporters at major publications. So she moved on to the law. Hedging her bets, she applied to Harvard and for a scholarship to spend a year in India. She got offers from both. “Maybe I made a mistake, but I went to Harvard Law School instead of India,” she said. Gloria Steinem ended up going on the trip to India.

“Answering a question in class was a chance to be humiliated”

Flora grew up in Brooklyn, New York, where she attended James Madison High School, the same school as Ruth Bader. (They did not overlap.) She was always at the top of her class but not “bookish,” she says. Once she got to Harvard Law, Flora recalls forming a bond with two other women there, Carol Simon and Betty Jean Oestreich. They roomed together and threw dinner parties, making a number of good friends among the men in the class. She generally felt welcomed at Harvard but was still aware that women were treated differently. She remembers the discomfort of being singled out during one professor’s “ladies’ day,” when only women—there were just two in the class, including Flora—had to answer all the questions. “And answering a question in class was a chance to be humiliated,” Flora says. As if that wasn’t enough, the women were also forced to sing for the class. Flora remembers practicing “Good King Wenceslas” for weeks in preparation. Read Justice Ginsburg’s memory of ladies’ day.

Flora was at the famous dinner party thrown by Griswold when he asked the women to explain why they were at Harvard Law, taking the place of a man. “[Ruth] and I were the only two women of, I don’t know, 50, 75 men,” Flora recalls. In response, Flora says, she made a joke: “ ‘Dean, I’m here looking for a husband.’ ”

In social settings, Flora saw Ruth’s intensity firsthand. “If she was at dinner at her house, which Marty, her husband would cook, she might excuse herself and go into the bedroom and work on a brief—when people were over,” Flora said. She said she admired it, even if it was unusual. “It was nice to be with Ruth when you had a legal issue to discuss,” she said. “Ruth even then had no small talk.”

“I was the only woman in the office, and they wanted a woman in the office”

After graduating, Flora remembers a frustrating string of interviews. “The only thing that kept me looking was that I knew that Ruth hadn’t gotten a job,” she said. “I felt if Ruth, who was first or second at law school, couldn’t get hired, I just had to keep looking.” Through connections, she landed a job as assistant counsel to Nelson A. Rockefeller when he was governor of New York. “It was just sheer luck,” she said. “I was the only woman in the office, and they wanted a woman in the office.” The job thrilled her. Read about Justice Ginsburg’s struggle to get her first job.

Flora was later hired by the powerhouse law firm Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy. The man who interviewed her was quick to dismiss her ambitions. “[He] said, ‘You know, we have no women partners. And I don’t think you’ll ever be a partner here,’ ” she recalls. She went into the firm’s real estate branch, unaware it lacked the prestige of other fields, but “it turned out that real estate got to be a really hot lucrative area, and I had a fabulous time.” Still, even after she handled a number of high-profile New York properties, the firm didn’t make her a partner. So, she left for another firm and made partner there. Six or seven years later, Milbank invited her back—this time as partner.

A pathbreaking real estate lawyer

During her time there, she saw a noticeable, though still not significant, increase of female hires. Some, like her, became partners, but “never in positions of real power at the firm,” she recalled. Even after she was elected president of the American College of Real Estate Lawyers—the first female president of the organization—she still felt the men resisted or even ridiculed her ideas. “It just wasn’t easy,” she said.

Flora worked with a developer on the New York Marriott Marquis at Times Square. The project, which was announced in the ’70s and opened in 1985, required the demolition of five historic theaters. Opponents sued, taking the case all the way to the Supreme Court. “We had like 17 lawsuits,” Flora said. “It was just a fascinating project, working with the state, the local government, the opposition.”

“Iconoclasts in very different ways”

Flora met her partner of 35 years or so in the 1960s, when he was known by the name F.M. Esfandiary. He was an Iranian novelist, developing a new philosophy that came to be known as transhumanism. “He felt that mankind is facing the dilemma of facing death, and he wanted to put that behind us,” Flora explained. He repeatedly changed his name—he believed people should not be defined by their name or nationality—eventually landing on “FM-2030.” FM also rejected the notion of marriage. They were romantic and intellectual partners: Flora edited one of his books and worked on a movie about his life and vision. The film, 2030, described Flora and FM as “iconoclasts in very different ways.” “Despite the lack of an exclusive or even official commitment to one another—FM even preferring the word friend to relationship—Flora and FM’s connection proved to be lifelong, lasting until FM’s suspension in 2000,” the film explains, using FM’s preferred term for death. His body was placed in a cryonics facility.

Flora still has ties to the deeply optimistic movement FM-2030 launched, but while her view of the trajectory of human society is positive, her take on her chosen industry is a bit more tempered. Asked about any further reflections on her time in the legal world, she quipped: “I just wish men were better.”

Betty Jean Shea, born 1934

Betty Jean Shea, born Betty Jean Oestreich, was an exceptionally bright and high-achieving student. The daughter of two teachers who moved often for work, she graduated high school in Scarborough, New York, as the top student in her class. She attended Wellesley, where she majored in geography and history, and graduated with honors. While there, she was dating a student at Harvard Law School, and she often attended his morning classes with him on the Saturdays before football games. She remembers being fascinated by the Socratic method of teaching. “I was hooked,” she said. She and her boyfriend broke up, but she still wanted to attend the top law school in the country. “I never considered any place other than Harvard,” she said.

“Of all the women in the class, I was most impressed with her”

The diversity of Betty Jean’s talents struck a young Ruth Bader Ginsburg. “Of all the women in the class, I was most impressed with her, because she had been both a model and an actuary,” the justice told Slate. In her time off between college semesters, Betty Jean had worked for the Conover Model Agency, and in high school, she had worked for the actuarial department of the New York Savings Bank Life Insurance Fund. Read Justice Ginsburg’s assessment of Betty Jean.

Betty Jean was confident she would excel at Harvard, but since she had a friend who had been among an even earlier group of women there, she knew it wouldn’t be easy. “She said it was challenging, but she also said it’s sometimes fun to be the only girl there.” The experience could be fun, Betty Jean said, but for the most part she felt she was ignored by the professors, with the notable exception of Barton Leach and his “ladies’ day,” which left her feeling under attack. Her fellow students were no better, often asking her what she was doing there. “Young men would blithely ask that question to you directly,” she said. “I’d just say, ‘I’m interested in the law, and I couldn’t figure out a better place to go.’ ” She found solidarity with her roommates Flora Schnall and Carol Simon. “We could tell stories and laugh about a great many things that wouldn’t be so easy to laugh at if you didn’t have them with you,” she said. “It made it easier to take it less personally.”

A marriage of equals

On the first day at Harvard, Betty Jean met her husband, Bob, in the library. They married in her third year. She regards that decision as the best one she ever made, and she said she had a marriage of equals, which she thinks was made possible in part by the fact that they never had children. The two supported each other throughout their careers, and life decisions were made based on whether they would be mutually beneficial. Bob, who died in 2000, had always respected her as a peer, she said.

Betty Jean’s first major job after graduation was as an attorney for the Federal Reserve Bank in New York, where she rubbed shoulders with influential New Yorkers. It was the best job she ever had, she said, but even there she faced discrimination: She said that she was hired by a man who felt “uncomfortable” hiring women and did so only to please his more progressive boss. She recalled that once, when attending a luncheon at the all-male New York Stock Exchange, she had to arrive through a freight elevator to a separate entrance, because the regular elevator was “for business, it was for men”—even though she was there to give a speech on a new regulation she had helped draft. Afterward, she called up the president of the New York Federal Reserve, whom she didn’t personally know, to complain. He promised not to send any more speakers to the exchange until they changed the policy. They did, and Betty Jean returned to the stock exchange many times—often taking the opportunity to remind the men in the room how she had once been treated. “I must admit, I enjoyed that,” she said.

“I was used to being listened to”

When she and Bob moved west a decade later, Betty Jean looked for jobs but had “a heck of a time even getting an interview,” she said. She had nearly secured a position at the legal department for one bank in San Francisco, only to be rejected after an in-person meeting with two men at the bank. “I came across a little too strong, perhaps a little too arrogant,” she said, but also noted that she’d been insulted at the basic questions they asked her. “I was used to being listened to and not being treated as a 12-year-old.” She ended up at Wells Fargo, where she worked for 20 years, becoming head of the law department for the Southern California branch. In retirement, she kept busy volunteering and breeding Salukis to enter dog shows, an activity she had pursued for decades.

When she reflects on her career, Betty Jean recognizes that she saw a major shift in how the legal field treated women. But she thinks it wasn’t enough. “I am still disappointed to the extent to which women are discriminated against and undervalued,” she told Slate.

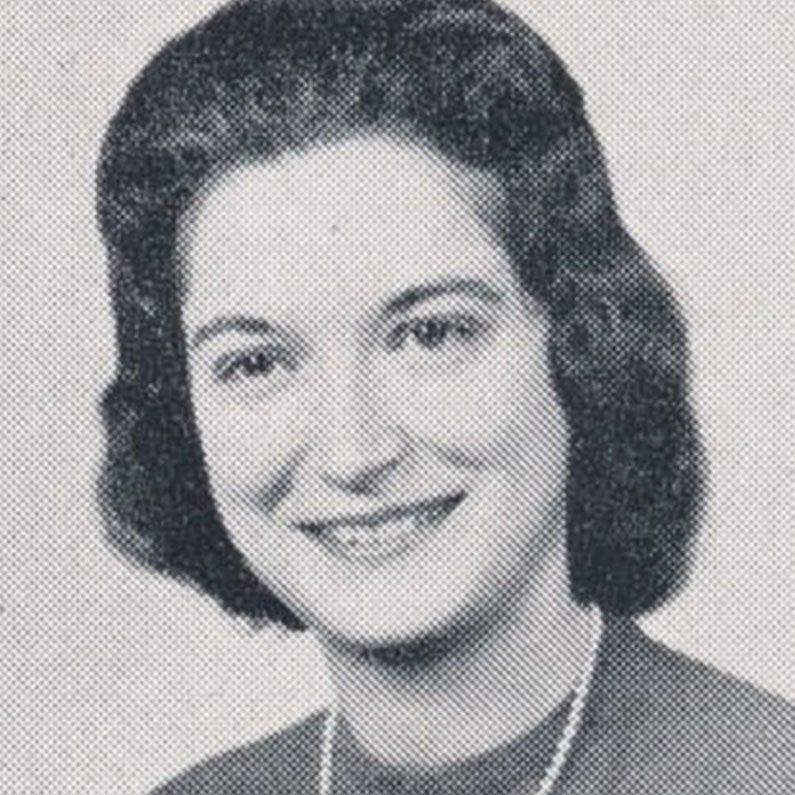

Alice Vogel Stroh, 1935–2007

Alice Vogel was not someone who felt an early call to practice law. At the University of Missouri, she was a good student, but she was more concerned with enjoying her college years than studying. “She knew all the places to go to sneak beer underage, she pulled pranks,” her daughter Elizabeth said. “And then she would be the one that was getting straight A’s without any effort.” Alice’s intelligence was confirmed by Ginsburg herself, who remembered Alice had been “the smartest girl, by far, in the class.” Alice’s father, a Harvard Law grad, promised to buy her a convertible if she followed in his footsteps. “I think she … didn’t want to disappoint him,” Elizabeth said. “I also think that once my grandpa dangled that, she got the bug that she was going to do something few women had met the challenge to do.” After she got the convertible, she never drove another kind of car the rest of her life.

Bitter law school memories

Alice’s family says that she never spoke much about her time at Harvard, and when she did, it was with bitterness. Her daughters theorized that her memories of the time were tainted by how she associated it with John Stroh, a law student a year ahead of her. They had grown up just a few blocks apart in St. Louis but met and married at Harvard. The marriage did not end well.

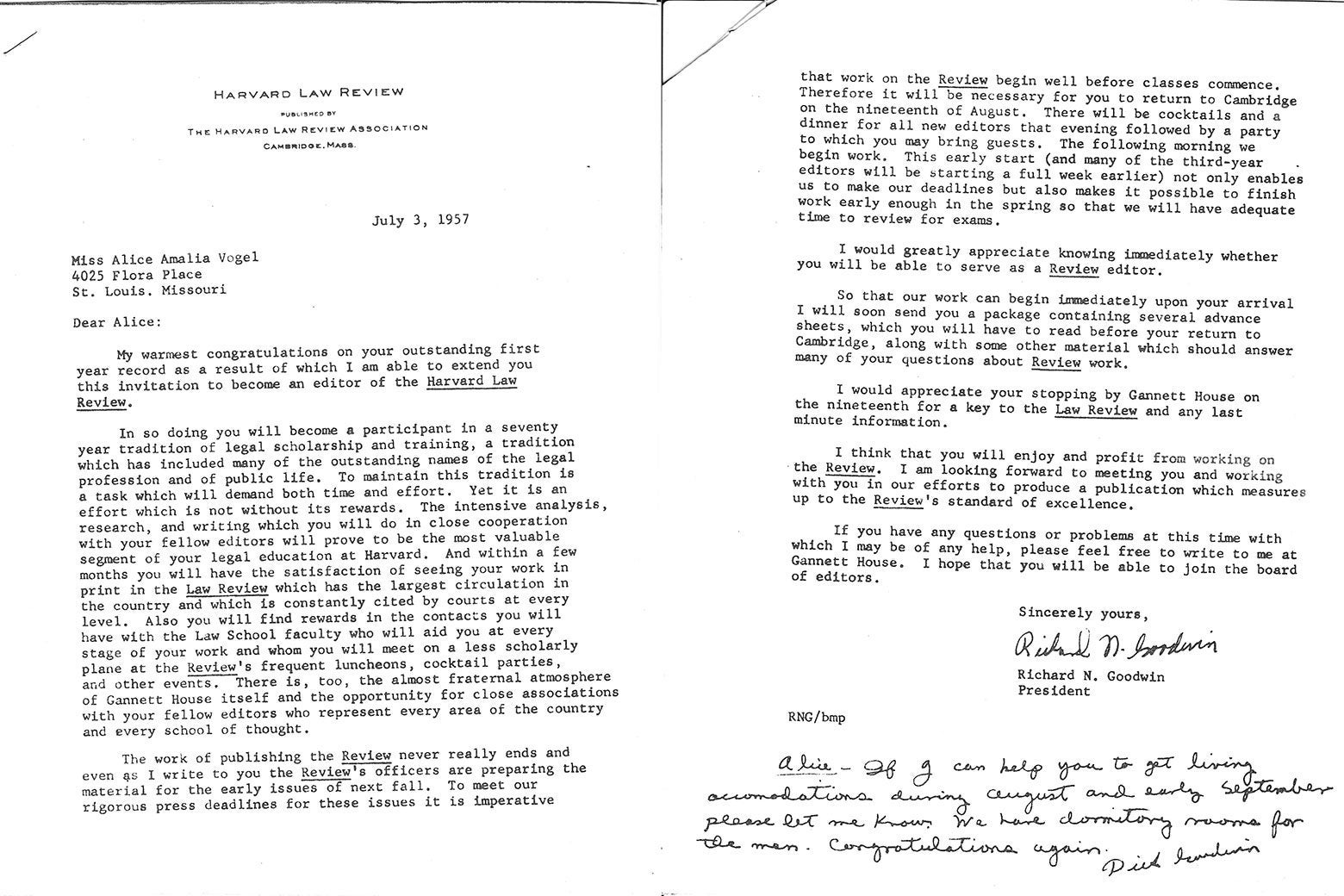

Alice’s daughter Chat also remembers her saying she was “shocked” by the level of competition at the school, but Alice did well regardless. Like Ruth Bader Ginsburg, she was selected to be an editor of the Harvard Law Review—an achievement that came with logistical difficulties, like needing to start the school year earlier in the summer, when there were no dorms available for female students.

“As soon as she stepped aside to have babies, the door closed quickly for her”

Despite having excellent grades, Alice was rebuffed by almost all the firms she applied to. She eventually found an opportunity at the agrochemical company Monsanto, which at the time was looking to hire women. She landed a job in their legal department—one of just a few women at the time doing corporate litigation. She stayed for eight years.

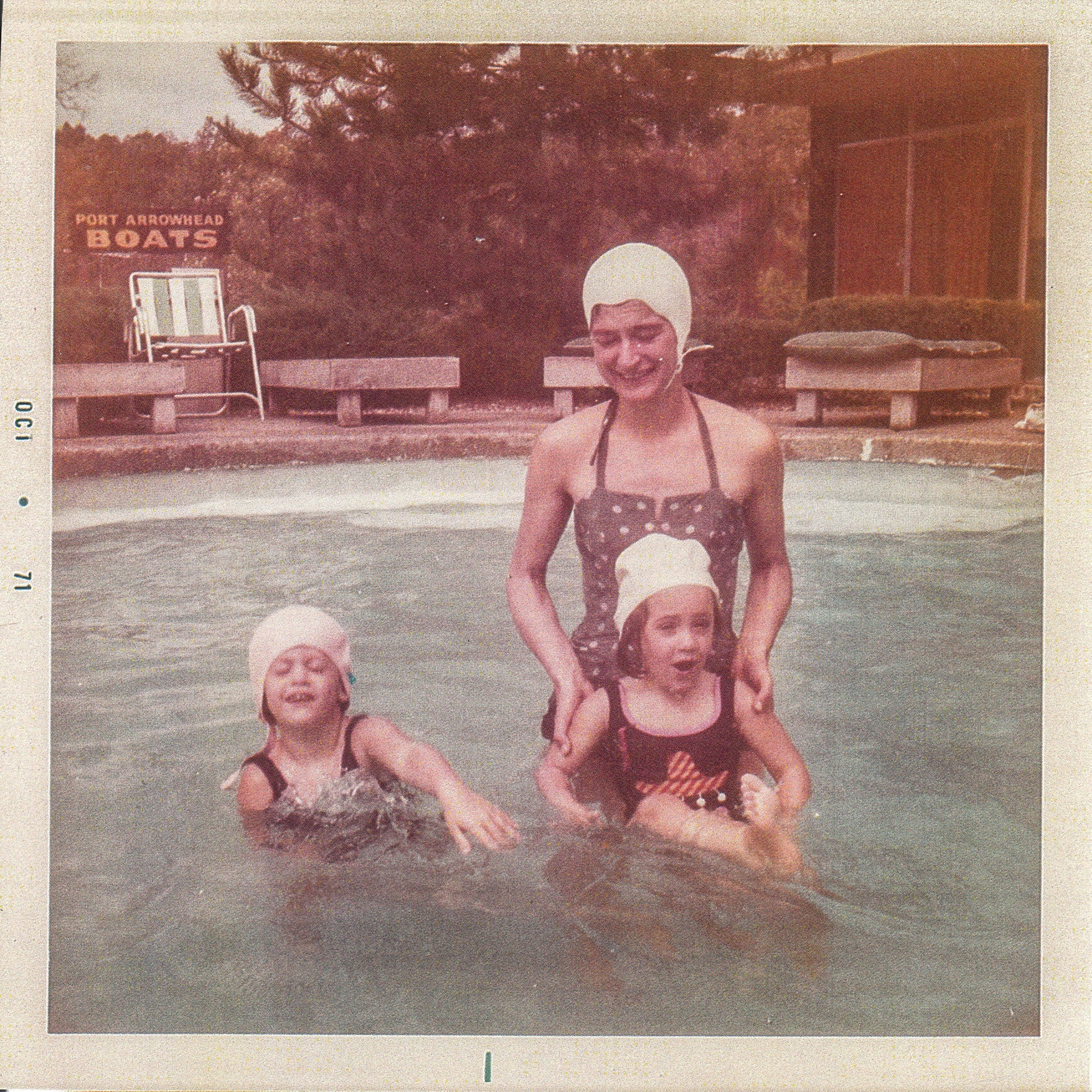

She left the job after she got pregnant, but it’s unclear whether she quit or was simply taking her maternity leave. Her daughter was stillborn. A grieving Alice wrote to Monsanto, telling them she would “not have the joy of being a mother” and asking to return to her job. Monsanto had already filled the position with a man. “She was almost pleading for them to reconsider taking her back,” Elizabeth said. “She had worked so hard to get to where she was, but as soon as she stepped aside to have babies, then that door closed very quickly for her.” She adopted her first of two daughters that same year and left the legal profession to become a full-time mother.

“She had to start at the bottom and prove herself again”

The couple had moved back to Missouri after graduating, and John had gone to work for Alice’s father’s law firm. But according to their daughters, his insecurities paired with her accomplishments slowly poisoned their relationship. “My mom’s grades and everything far surpassed my dad’s, which caused a lot of stress on their marriage,” Chat said. “My mom would say the only reason he was able to get a job was because of her dad. There was a lot of tension there, that her job she got on her own merit, and he had to have help from family.” They separated in the mid-1980s. (John passed away in 2010.) Afterward, she put all her energy into being a full-time parent—volunteering for every field trip, keeping the logs for her daughters’ swim teams, sewing all their clothes. Her daughters describe her as a perfectionist, and not all that affectionate. “She did say she felt she’d been cheated,” said Chat. “That she was willing to stop working to be a wife and mother, but then all of a sudden, her spouse had left.”

“There was always that what if”

Alice began looking at legal jobs again when she was in her 50s, after her children had left the house. In 1986, she got hired as a paralegal at the St. Louis law firm Husch and Eppenberger. “She was the one doing the grunt work by a light in the evening, when some of the young yuppie attorneys were the ones getting the glory,” Elizabeth said. “I knew how hard my mom was working. She really had to start at the bottom and start proving herself again.”

Alice became an associate estate planner and was placed with older attorneys she felt more comfortable around. “It had been such a struggle for her to go back to work and prove herself. Towards the end, she at least felt she’d found a spot in that firm that worked for her,” Elizabeth told Slate. Her daughters were still left to wonder if she sometimes regretted her decision to stop working while they were young. “There was always that what if” with their mother, Elizabeth said, “what if things had gone differently.”

Eleanor Voss, 1936–1958

One of the women who attended Harvard Law School with Ginsburg and her classmates never made it to graduation: Eleanor Voss died in the fall of her final year of law school.

Contemporaneous newspaper coverage of her short life suggests she was remarkably smart and ambitious. Voss grew up in New York City and attended the prestigious High School of Music and Art. In 1952, when she was just a sophomore, she was selected to participate in an experimental program allowing her to skip junior and senior year and head straight into college. She enrolled as an international studies major at Goucher College, a then-women’s liberal arts college in Baltimore, where she excelled, becoming the editor of the weekly student newspaper, and graduating Phi Beta Kappa when she was just 19.

On Nov. 13, 1958, Voss was riding as a passenger on a motorized scooter when it collided with a taxi cab in a Cambridge, Massachusetts, intersection, killing her. After her death, her friends and classmates from Goucher created a fund, the Eleanor Voss ’56 Fellowship, to send one graduating senior to law school each year. It continues today.

Read Slate’s full interview with Ruth Bader Ginsburg here. Listen to our special audio series, “The Class of RBG,” on Apple Podcasts or below.

Photo credits: Yearbook photos from the Harvard Law School yearbook. All other photos and texts courtesy of the women or their families.

Update, July 21, 2020: This piece was updated with Kendra Nordin Beato’s full name.