The Heart of the Comets: The Story of Kim Perrot

Everything was falling apart. Players were bickering, the red-clad Houston fans were losing hope, and Head Coach Van Chancellor was out of ideas. He looked up at the scoreboard to reaffirm what he already knew: His team was down 12 points with 7 minutes and 24 seconds to go. It was game two of the WNBA Finals, and the Houston Comets had already lost the first bout in the best-of-three series with the Phoenix Mercury two nights prior in Arizona. Now they were back on their home floor, back in Houston, and throwing it all away.

In a last-ditch move, exasperated, Chancellor whistled for a timeout—but he didn’t have anything to say.

The Comets, the championship-winning women’s team that had been racking up points and accolades since it was formed in 1997, just a year before, weren’t playing together, plain and simple. Not playing the brand of basketball that had helped them win the WNBA’s first ever league championship the previous summer and compile a league-best 27-3 record in year two. He knew it, they knew it, everybody in what was then Houston’s Compaq Center knew it. But he had called the timeout and he had to say something.

Crouching down in front of them, Chancellor opened his mouth to speak, but was warded off by a small hand.

“I got this, Coach,” said a voice, and into the middle of the huddle stepped the team’s heart and soul. Not Tina Thompson, Sheryl Swoopes, or Cynthia Cooper, the team’s perennial All-Stars that made up the “Big Three,” the trio that had helped already establish the team as the nascent dynasty of women’s basketball. Rather, it was tiny point guard Kim Perrot who jumped into the center of the cluster, right where the heart belongs.

“He turned that timeout over to Kim, and Kim just rallied us,” remembers Cooper over two decades later. “She was encouraging, but she was stern, and she had always been that type of motivator. When we went out to play, we already knew we’d win.”

Thompson agrees. “She just had that personality where she would say things and you understood the feeling and the emotion of what it was that she was saying—and it could change the whole climate of a game just like that."

The buzzer sounded, signaling the end of the timeout, and a new team took the floor—synchronized, composed, ready to show the world they were the best team in women’s basketball. The Comets erased the deficit before the clock ran out, forced the game into overtime, and ultimately defeated Phoenix.

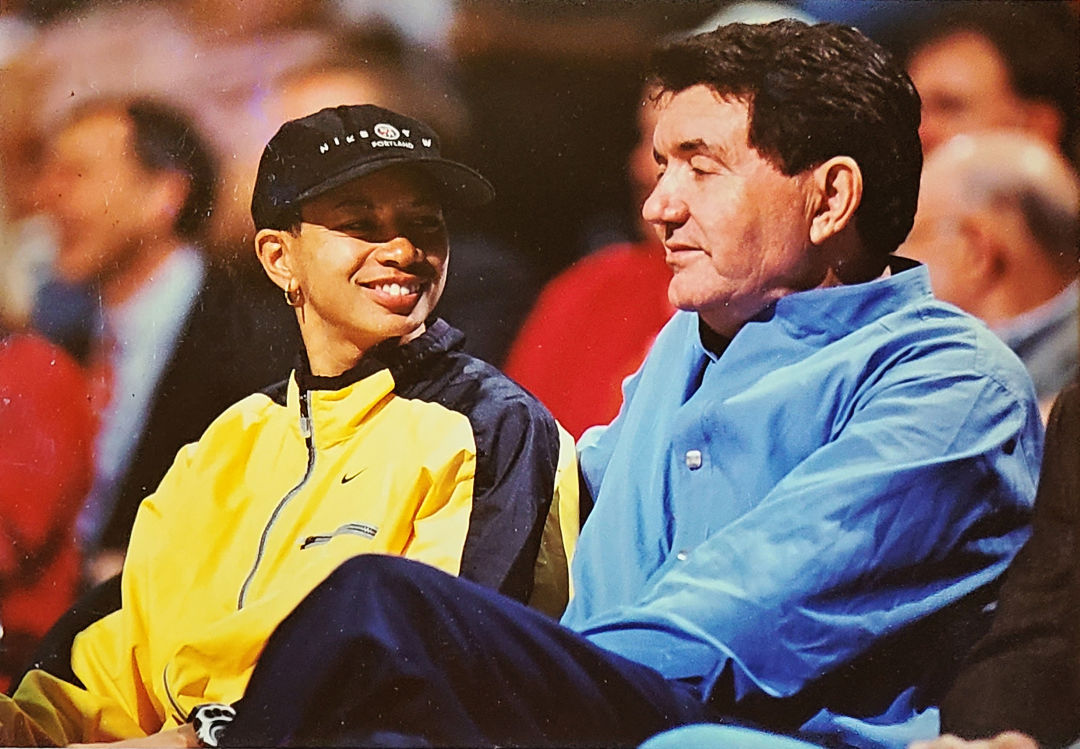

Perrot and Chancellor became fast friends.

Image: Courtesy of Van Chancellor

Three nights later the Comets were back in the Compaq Center, easily winning game three and securing the 1998 WNBA championship, their second in two years.

“Who’d have thought Kim Perrot would be a two-time WNBA champion?” Perrot said when she and her 11 teammates were presented with their championship rings.

The Big Three got most of the attention that night—photographers loved taking pics of Thompson, acclaimed for her skills on the court, elegant, tall, and always sporting red lipstick—but everyone on the team knew that it was the 5’5” Louisiana-born point guard Perrot who’d pulled them together and made this happen.

“When she spoke, we listened,” Thompson says.

It was an amazing night, but one that would prove to be bittersweet for the legendary team. They thought this was just the beginning, that this was another step toward building a women’s basketball dynasty in Houston. What nobody knew at the time was that there was a problem with their beating heart. Inside Perrot, outlaw cells were already dividing and multiplying, and within a year she would be gone. This was the last WNBA game Perrot would ever play.

During the 1990s the professional sports landscape of Houston was a tasting menu of success. The Oilers had won Houston’s love with seven consecutive playoff appearances from 1987 to 1993 led by quarterback Warren Moon. The Houston Rockets of the National Basketball Association brought back-to-back Larry O’Brien championship trophies to the city in 1994 and 1995, and had the legendary Hakeem Olajuwon leading their roster. The Astros had Jeff Bagwell on deck and would go on to notch seven-straight winning seasons through 1999, including three consecutive National League Central Division titles. Even H-Town universities were doing well: the Rice Owls, not traditionally looked to for athletic accomplishments, were emerging as a national brand in college baseball under legendary head coach Wayne Graham, earning their first College World series appearance in 1997. For the first time ever, Houston truly had game in almost every sport.

The Comets arrived in the city during the summer of 1997. The team was one of eight established by the newly minted WNBA in a bid to make women’s basketball as exciting and essential to American life as the NBA. The league’s commissioner, Val Ackerman, had wisely used the 1996 summer Olympic Games in Atlanta to trumpet the impending arrival of the new league, and she’d catalyzed a 54-game tour for the women’s national team leading up to the 1996 Summer games to generate interest.

The WNBA teams were owned and operated by existing NBA franchises with the hope that the existing organizational infrastructures and marketing blueprints would allow for quick and lasting growth. Still, complicating the launch of the league was the fact that another women’s professional league was beginning at the same time, the American Basketball League, and the challenge of drawing in new fans to the WNBA was compounded by a battle for players with the ABL.

While more than half of the Olympic team members opted for the ABL, which played during the traditional basketball season and offered a higher average salary, Ackerman and her associates were able to recruit three of the biggest names in women’s basketball to the WNBA: Lisa Leslie, Rebecca Lobo, and Swoopes. Each was placed in a market close to her respective home. Swoopes, a native Texan who’d led Texas Tech to the NCAA championship in 1993 and then become a member of the barnstorming Olympic team, landed in Houston with the Comets.

The way both Ackerman and Chancellor describe it, the formation of the greatest team in WNBA history was merely a string of happy accidents. Signing Swoopes was a coup—between the exposure she’d gained on the USA Olympic team and becoming the first woman with her own signature sneaker (the Air Swoopes), she was certain to become the face of the embryonic franchise—but the dividends were frozen for a year when she announced that her pregnancy with her son, Jordan, would sideline her for the majority of the inaugural season. The Comets also signed 34-year-old Cooper, hired Chancellor from the collegiate ranks at Ole Miss, and selected Thompson out of Southern California with the first pick in the 1997 draft. There was no way to know at the time, but that would be the core of the greatest dynasty in league history: A sidelined star, a 34-year-old, a rookie, and a head coach with a southern accent as thick as roux.

With the season approaching, Chancellor still didn’t have a point guard, though, someone to distribute the ball to what would ultimately become his “Big Three.” He held a tryout, looking at 62 hopefuls flown in from across the country. Among them was Perrot, tiny but scrappy. A Lafayette native, she’d played for the University of Southwestern Louisiana (now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette) on scholarship from 1987 to 1990, breaking 26 records, and spent the next few years playing overseas. She immediately caught the attention of other Comets staffers, but not Chancellor himself.

“I didn’t particularly like her game. It was too wild,” he says now. She was one of seven point guards asked to the Comets training camp, even though Chancellor, unlike the rest of his staff, voted to cut her. “All the people around me liked her, so I kept her.”

By the time the first few games of the season were on the horizon, Perrot was set to share the point guard position with her final rival for the starting spot.

Although the birth of the Comets was quiet in comparison to, say, that of the Texans in 2002, the WNBA generated enough momentum in the years leading up to the 1997 launch to surpass its own projections for attendance in year one.

The Comets struggled to find a rhythm, beginning the 1997 season with a 4-3 record for their first seven games. It became clear that alternating between the two point guards was throwing off the team’s mojo. Chancellor finally made the call on the way to the airport for an away game: Perrot had made the team.

“It’s about time my coach wised up!” Perrot replied.

It was the beginning of a friendship as strong as any Chancellor has ever had with a player. Perrot’s playful feistiness carried over beyond the court. She loved to play dominoes on the road and talk trash as if it were a matchup with the New York Liberty (the only team that had defeated the Comets through the first seven games of the 1997 season ).

“She’d always come in the door of my room, and tell my wife, ‘Miss Chancellor, I’m gonna whip your husband tonight. Try to pep him up when I get through.’ It was just a whale of a time,” he remembers.

Van Chancellor

Image: Monica Fuentes Carroll

That was who Perrot was. She loved a good-sized crowd and knew how to work one, “raising the roof” to get an even bigger response after stealing the ball or making yet another crucial basket. She knew how to charm, to make those around her feel as if, when she’d done something amazing, they’d almost done it too.

The energy that first made Chancellor wary of signing Perrot proved infectious and invigorating. When she was taken out of drills at practice, teammates looked down the sideline to find her doing sit-ups. Everyone loved Perrot—teammates, staff, and Comets fans—and Chancellor soon found himself depending on her to captain the team on the floor, a difficult task when dealing with so many phenomenal talents on one roster.

“Everybody talks about spark plugs. I don’t really think she was a spark plug. I think she was a stick of dynamite that got us going,” says Cooper now. Perrot quickly became Cooper’s best friend on the team. “She didn’t back down for anyone. Kim and I were friends, but when it came to us practicing and her defending me, we once almost had a fight. When it came to her rallying us and checking us whenever we were doing something that we weren’t supposed to be doing, she was that person. Chancellor didn’t have to do it because Kim was on the court.”

Although Perrot was a facilitator for the Comets, her own court skills were considerable. She’d earned a reputation in college for scoring, ending her collegiate career with over 2,000 points, including a 58-point performance, still the second-highest single-game output in Division I history. She led the nation in scoring her senior year with an average of 30 points per game.

“She could do it all, and she morphed into what we needed her to be in order to be successful, and that’s a testament to her winning mentality,” says Cooper, now the head coach at Texas Southern.

After the slow start, the team went 14-7 the rest of the way in 1997 with Perrot as the starting point guard. Fans were coming out to see Houston’s newest winner, and were treated to a show beyond the on-court product. Rockets players were fixtures in the lower arena. Leslie Alexander, who owned both the Rockets and the Comets, sat in the first row and was, as Commissioner Ackerman puts it, “visibly proud of the accomplishments of the team and was very supportive during those critical early years.”

Chancellor emerged from the tunnel 40 minutes prior to tip-off. Music played from the speakers overhead and dozens of basketballs pitter-pattered against the floor as the players warmed up. People trickled in slowly but the diehards, those who arrived early to soak up the pregame ambience, lined the first few rows of seats. The coach made his way toward them not with a coach’s clipboard or a water bottle, but a bag of Jolly Rancher candies, reaching inside and spraying them over the swath of fans as if feeding geese.

“It was the complete package,” says Ackerman. “It was great theater, and I think, on some level, pro sports is about theater. It’s about entertainment.”

The result was nightly attendance numbers that surpassed league projections. Ackerman says that she and her team had projected average crowds of “between three and five thousand” for year one. The Comets averaged more than 9,000 in year one, and roughly 12,000 for years two, three, and four.

“People were talking about us,” Tina Thompson remembers. “I had friends in the NBA and they were excited about it. The fact that the guys were coming to the games gave a great sense of camaraderie and support. There were constant fixtures at our games. Nick Van Exel, Sam Cassell, Cuttino Mobley, Steve Francis, James Posey, Moochie Norris, a lot of those guys were on the Rockets team, some of them not. It was very cool because it was a very vibrant time in Houston, for football, for basketball. So many different athletes lived in Texas even if it wasn’t for their home team, they had homes there. It was really cool to see the energy.”

Winning helped. As was customary in the city at the time, the Comets earned a berth in the postseason in year one. The playoffs were a single elimination format during the league’s first season and, after knocking out Charlotte in round one, the Comets prepared to face off with the New York Liberty, the team that handed them three losses to begin the season. Perrot, normally steely, was visibly rattled the night before the game and told Cooper it was because she had never won a championship before.

“I said, ‘Well, you are going to win one tomorrow,’” remembers Cooper, who was named league MVP each of the first two seasons. “That’s the type of team camaraderie that we had. That’s the type of confidence we had in the work that we put into not only the 1997 season, but ’98, ’99, and 2000.”

After the team topped New York, 65-51, to earn the first championship trophy, many Comets players headed overseas to play during the traditional winter basketball season. Since Perrot stayed in Houston, Chancellor tapped her to accompany him for elementary school appearances across the city to compete in shooting competitions in front of the kids. Perrot, with Chancellor’s initial reservations about her forgiven but not forgotten, would not only win every time, but run up the score, shaping the bludgeoning into a valuable moral for the kids.

“Never, ever give up,” she said, before putting a hand on Chancellor’s shoulder. “My coach did everything he could not to have me on the team, but, finally, once he started playing me, I won him a championship.”

Chancellor remembers a child raising his hand and asking why she didn’t shoot more during the games. Perrot explained that it was about doing what was best for the team.

“Let me tell you the reason I don’t shoot: we’ve only got one ball, and that’s for Swoopes, Thompson, and Cooper,” she said. “If I shoot, I’ll be on the bench, and I’d rather play.’”

If the team was finding its footing along with the rest of the league in 1997, it separated itself as the dominant force in 1998. Swoopes was back, giving the team three strong-natured alphas who, indeed, all wanted the ball. Perrot held the divergent personalities together like the stems of a bouquet.

“That first year I didn’t really get an opportunity to bond with Kim very much because that was the year I was pregnant, so I wasn’t in Houston a lot,” says Swoopes. “When I did finally come, Kim was the one player that she just made me feel welcome. It was like, ‘Listen, all right, you took time off, you had your baby, but this is what we’re all about, winning championships, so just go and get yourself ready to come back.’”

“She’s the only person I know who would yell at me and tell me not to take a shot on the court,” adds Cooper. “She had enough confidence in her game and who she was to say, ‘Coop, don’t shoot that shot! Pass the ball!’ And I was like, ‘Who are you talking to?’ and she would say, ‘You! And if you want me to pass you the ball again, you are going to pass the next one, you understand me?’ She was that type of player and you respected her for that.”

Of all four championship seasons, the team played its best basketball in year two, torching the league to finish with a 27-3 record heading into the playoffs. They swept the Charlotte Sting in the first round again before meeting the Phoenix Mercury in the Finals, dropping game one of the series and nearly losing all hope of a four-peat, down 12 points with seven minutes left to go in game two. That’s when Perrot rallied them in that fateful fourth quarter timeout.

“That conversation in the huddle did change us instantaneously,” remembers Thompson, now the head coach at University of Virginia, “and from that moment on in that game we were different.”

“She woke us up,” adds Cooper of the pivotal timeout. “She just woke us up to all band together to make a comeback and win that game and then win the championship. That’s just a testament to her leadership.”

Houston erased their deficit, won game two in overtime, and, three nights later, won the deciding game three at home in the old Compaq Center. Two years, two championships. They celebrated on the court, basking in the adulation of a loving fan base as they accepted the trophy. Team personnel eventually retired to the locker room for further celebration.

Without thought, Perrot took off her sweaty number 10 jersey for the last time.

In February of 1999 Chancellor’s phone rang while he was standing on the fairway of hole 14 at Meadowbrook Farms Golf Club in Katy. It was a known caveat to any round you golfed with the coach: he always kept his phone on. Everyone paused as he answered. It was the Comets’ team trainer. “Go to the clubhouse and call me back,” she said.

Standing in an empty room of the clubhouse, Chancellor could hardly believe what he was hearing. Perrot had gone to the doctor that February after noticing some weakness in her right arm. There was no obvious reason for it, so she’d been referred to specialists, including oncologists at MD Anderson. It was there she’d been told she had lung cancer.

The doctors said the prognosis wasn’t good, but Perrot was determined to fight. “This has been a tough moment for me, but I’ve always had to battle,” she told the New York Times shortly after the news broke. “And this is just another battle. I believe with all my heart and faith in God that I will overcome this. My goal is to be back on the basketball court doing what I’ve been doing the last two years.”

She didn’t play during the 1999 season, undergoing brain surgery within days of her diagnosis. (The cancer had already metastasized from her lungs to her brain.) It was clear she wouldn’t be on the court that year, but even as she was undergoing chemotherapy, Perrot made a point of coming by practices and attending games. Slowly, however, her appearances became less frequent.

The team had vowed to win “3 for 10” (Perrot’s jersey number), intent on making it to the championship again. It was the only thing they could think to do—they couldn’t fight Perrot’s cancer off for her, but they knew how to win. They continued to triumph with the game, but, as Thompson notes, there were days when the emotional toll of the situation seemed insurmountable as they prepared to take the floor.

“We were crying in the locker room before the game, every single game,” Thompson says. “You start crying and then another teammate starts crying. That was the energy in our locker room and it took an incredible emotional toll. But being resilient, being focused and kind of dialed in to why we were doing it, you can tap into a different place in yourself.”

By the back half of the season chemotherapy had left Perrot so weak she was no longer coming to games. But she was always watching. During a home game against Sacramento, the Comets blew a 19-point lead. Perrot was watching at home and could see that her team was unraveling. Perrot marshalled her strength to make the trek to the arena, sidled up behind the bench, and silently put her hand on Chancellor’s arm.

“During a timeout I thought some kid had come out of the stands and she had her hand on my shoulder,” recalls Chancellor. “I turned around and said, ‘Kimbo? What are you doing here?’” and she said, ‘Coach, I felt like somebody needed to love ya. I figured the other three were mad at you, so I left the house just so I could tell you how much I care about ya.’”

Chancellor took that information in, studying the thin, frail face looking up at him. “I cried right there on the sideline,” he says now, his voice growing husky. “That was the most heartwarming thing that ever happened to me as a coach.”

Perrot died on August 19, 1999, with Cooper there, holding her hand. It was the day before the team was slated to travel to Los Angeles to play its penultimate regular season game. They almost canceled, but they all knew that was the last thing Perrot would have wanted. Everyone was a mess, though. Cooper, who’d also lost her mother to cancer six months before, watched from the sidelines, sitting out the first game of her professional career. Swoopes and Thompson were vying for the ball, but the crew as a whole was sluggish and unfocused. Chancellor lost his temper at a call and was thrown out of the game by a referee. He was allowed back in after Thompson approached the refs and pleaded for some empathy, but Los Angeles won. It was too much, too soon.

Houston still managed to finish the regular season with a league-best record of 26-6. Less than a week later they were back in Los Angeles for the start of the playoffs, but this time they were ready to play as a team and determined to win—for Perrot. “We all tried to turn that situation into something positive, especially for myself,” Cooper later told theundefeated.com. “You know I was devastated. She was my best friend, and I just really wanted to pay a tribute.”

And, as had always been the case, when Perrot was behind the Comets, they were amazing. Cooper alone scored 24 points during that game. The team avenged the previous loss to the Los Angeles Sparks in the first round, setting up a Finals series with the New York Liberty. The final game was back in the Compaq Center.

New York fought hard, but there was no way any other team could fight as hard as the Comets did. They won 59 to 47, and the packed arena exploded with cheers as the final buzzer went off. Fans held up “3 for 10” and “3 for Kim” signs, and the noise was something none of the players would ever forget, Swoopes says.

Cooper grabbed Perrot’s jersey, holding it high over her head so everyone would see it as she took a final lap around the court. She was smiling but her face was streaked with tears. The whole team was intent that Perrot would get the credit she deserved.

“I think when the season was over, we won the championship, we celebrated a little bit, but we did it for Kim,” Swoopes says. “In that moment all of us were like, whoosh, you know? We could breathe now, and we could truly take time away from the game and go grieve and deal with the loss of such a remarkable, inspiring, courageous human being.”

In an emotional ceremony, Perrot would be awarded a posthumous third championship ring, and her number was retired, a first for the league. When then-president Bill Clinton invited the team to the White House to celebrate their third consecutive championship win, Perrot’s sister was also in attendance and Clinton praised how the Comets and their coach had overcome such a devastating loss. “Adversity breaks some people,” Clinton said in the Rose Garden. “It caused you to break records.”

“It all just added to the storyline,” Commissioner Ackerman observes now. “This group of women was carrying just intense sadness and this loyalty and this desire to do it for Kim. You don’t see that much.”

The next year the Comets went 27-5 and won their fourth-consecutive title. Perhaps most impressive was the fact that they didn’t lose a single game in the playoffs. Swoopes became the second Comets player to earn the league’s MVP award in just four seasons of play following Cooper’s back-to-back trophies in 1997 and 1998. Cynthia Cooper was named Finals MVP for the fourth-consecutive year.

Swoopes, Cooper, and Thompson were all named to the All-Star game for the second time after the establishment of the event the previous year. It was another season of dominance, but then, swiftly and rather quietly, the reign came to an end.

Chancellor, Cooper, Tammy Jackson, and Swoops hold trophies representing four straight WNBA championships after an August 2000 Downtown Houston parade.

Cooper retired after the fourth season, and Swoopes tore her ACL and missed the fifth. Thompson was still there, but the team never regained its footing. And in 2002 the Houston Texans came to town and Houstonians regularly chose preseason football over showing up for WNBA games. The team changed ownership, arenas, and coaches over the next few years while attendance numbers slowly dwindled from above 12,000 to below 7,000 by the team’s final season in 2008, mirroring a league-wide downward trend. After Chancellor took the team to the playoffs every season but one, the Comets missed the postseason each of their final two seasons under new coach Karleen Thompson. Less than a decade removed from the greatest team achievement in league history, the Houston Comets folded. And as has happened so often, Houstonians moved on.

“In Houston we had the Comets, and they really were Comets. If you look at the definition, it really was like they were a burst of light that came out of nowhere and kind of passed through the sky in this spectacular fashion, and then it was gone,” says Ackerman.

The team was integral to the league’s beginning and growth, helping it outlast the competing ABL, which folded midway through its third season in December of 1998. Even if the Comets’ name and accomplishments don’t resonate as far and wide as a similar run by a men’s team would, their legacy within the women’s game is indelible.

And what about Perrot? Well, her jersey hangs from the Toyota Center ceiling along with that of Swoopes, and the WNBA’s Sportsmanship Award was renamed after her. The court where Perrot grew up playing in Lafayette now bears her name as well. She serves as an example to young players who believe themselves to be too small, too under-the-radar, too anything, Cooper says. She was just 32 when she died, but Swoopes for one is confident that she, Chancellor, Thompson, Cooper, and the others who loved Perrot will keep her memory alive. Swoopes says there isn’t a day that goes by, even today, when she doesn’t think about her friend.

“She just had that never-say-quit, never-say-die attitude and was always a fighter,” Swoopes says. “Even right now, me sitting here talking to you, she’s probably saying, ‘Don’t you cry, that’s not who I was. Be strong.’ She was just tough. She was tough and she represented hope and opportunity. That’s exactly who Kim Perrot was.”