By the end of last year, anyone who had been paying even passing attention to the news headlines was highly likely to conclude that everything was terrible, and that the only attitude that made sense was one of profound pessimism – tempered, perhaps, by cynical humour, on the principle that if the world is going to hell in a handbasket, one may as well try to enjoy the ride. Naturally, Brexit and the election of Donald Trump loomed largest for many. But you didn’t need to be a remainer or a critic of Trump’s to feel depressed by the carnage in Syria; by the deaths of thousands of migrants in the Mediterranean; by North Korean missile tests, the spread of the zika virus, or terror attacks in Nice, Belgium, Florida, Pakistan and elsewhere – nor by the spectre of catastrophic climate change, lurking behind everything else. (And all that’s before even considering the string of deaths of beloved celebrities that seemed like a calculated attempt, on 2016’s part, to rub salt in the wound: in the space of a few months, David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, Prince, Muhammad Ali, Carrie Fisher and George Michael, to name only a handful, were all gone.) And few of the headlines so far in 2017 – Grenfell tower, the Manchester and London attacks, Brexit chaos, and 24/7 Trump – provide any reason to take a sunnier view.

Yet one group of increasingly prominent commentators has seemed uniquely immune to the gloom. In December, in an article headlined “Never forget that we live in the best of times”, the Times columnist Philip Collins provided an end-of-year summary of reasons to be cheerful: during 2016, he noted, the proportion of the world’s population living in extreme poverty had fallen below 10% for the first time; global carbon emissions from fossil fuels had failed to rise for the third year running; the death penalty had been ruled illegal in more than half of all countries – and giant pandas had been removed from the endangered species list.

In the New York Times, Nicholas Kristof declared that by many measures, “2016 was the best year in the history of humanity”, with falling global inequality, child mortality roughly half what it had been as recently as 1990, and 300,000 more people gaining access to electricity each day. Throughout 2016 and into 2017, alongside Collins at the Times, the author and former Northern Rock chairman Matt Ridley – the title of whose book The Rational Optimist makes his inclinations plain – kept up his weekly output of ebullient columns celebrating the promise of artificial intelligence, free trade and fracking. By the time the professional contrarian Brendan O’Neill delivered his own version of the argument, in the Spectator (“Nothing better sums up the aloofness of the chattering class … than their blathering about 2016 being the worst year ever”) the viewpoint was becoming sufficiently well-entrenched that O’Neill seemed in danger of forfeiting his contrarianism.

The loose but growing collection of pundits, academics and thinktank operatives who endorse this stubbornly cheerful, handbasket-free account of our situation have occasionally been labelled “the New Optimists”, a name intended to evoke the rebellious scepticism of the New Atheists led by Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett and Sam Harris. And from their perspective, our prevailing mood of despair is irrational, and frankly a bit self-indulgent. They argue that it says more about us than it does about how things really are – illustrating a certain tendency toward collective self-flagellation, and an unwillingness to believe in the power of human ingenuity. And that it is best explained as the result of various psychological biases that served a purpose on the prehistoric savannah – but now, in a media-saturated era, constantly mislead us.

“Once upon a time, it was of great survival value to be worried about everything that could go wrong,” says Johan Norberg, a Swedish historian and self-declared New Optimist whose book Progress: Ten Reasons to Look Forward to the Future was published just before Trump won the presidency last year. This is what makes bad news especially compelling: in our evolutionary past, it was a very good thing that your attention could be easily seized by negative information, since it might well indicate an imminent risk to your own survival. (The cave-dweller who always assumed there was a lion behind the next rock would usually be wrong – but he’d be much more likely to survive and reproduce than one who always assumed the opposite.) But that was all before newspapers, television and the internet: in these hyper-connected times, our addiction to bad news just leads us to vacuum up depressing or enraging stories from across the globe, whether they threaten us or not, and therefore to conclude that things are much worse than they are.

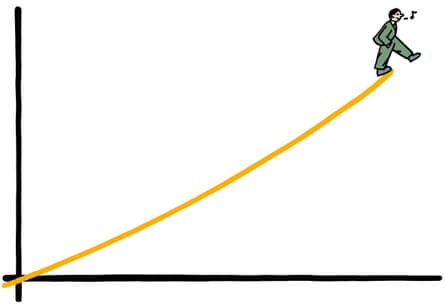

Really good news, on the other hand, can be a lot harder to spot – partly because it tends to occur gradually. Max Roser, an Oxford economist who spreads the New Optimist gospel via his Twitter feed, pointed out recently that a newspaper could legitimately have run the headline “NUMBER OF PEOPLE IN EXTREME POVERTY FELL BY 137,000 SINCE YESTERDAY” every day for the last 25 years. But none would have done so, because predictable daily events, by definition, aren’t newsworthy. And you’ll rarely see a headline about a bad event that failed to occur. But surely any judicious assessment of our situation ought to take into account all the wars, pandemics and natural disasters that might hypothetically have happened but didn’t?

“I used to be a pessimist myself,” says Norberg, an urbane 43-year-old raised in Stockholm who is now a fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute in Washington DC. “I used to long for the good old days. But then I started reading history, and asking myself, well, where would I have been in those good old days, in my ancestors’ northern Sweden? I probably wouldn’t have been anywhere. Life expectancy was too short. They mixed tree bark in the bread, to make it last longer!”

In his book, Norberg canters through 10 of the most important basic indicators of human flourishing – food, sanitation, life expectancy, poverty, violence, the state of the environment, literacy, freedom, equality and the conditions of childhood. And he takes special pleasure in squelching the fantasies of anyone inclined to wish they had been born a couple of centuries back: it wasn’t so long ago, he observes, that dogs gnawed at the abandoned corpses of plague victims in the streets of European cities. As recently as 1882, only 2% of homes in New York had running water; in 1900, worldwide life expectancy was a paltry 31, thanks both to early adult death and rampant child mortality. Today, by contrast, it’s 71 – and those extra decades involve far less suffering, too. “If it takes you 20 minutes to read this chapter,” Norberg writes at one point, in his own variation on the New Optimists’ favourite refrain, “almost another 2,000 people will have risen out of [extreme] poverty” – currently defined as living on less than $1.90 per day.

These barrages of upbeat statistics seem intended to have the effect of demolishing the usual intractable political disagreements about the state of the planet. The New Optimists invite us to forget our partisan biases and tribal loyalties; to dispense with our cherished theories about what is wrong with the world and what should be done about it, and breathe, instead, the refreshing air of objective fact. The data doesn’t lie. Just look at the numbers!

But numbers, it turns out, can be as political as anything else.

The New Optimists are certainly right on the nostalgia front: nobody in their right mind should wish to have lived in a previous century. In a 2015 survey for YouGov, 65% of British people (and 81% of the French) said they thought the world was getting worse – but judged according to numerous sensible metrics, they’re simply wrong. People are indeed rising out of extreme poverty at an extraordinary rate; child mortality really has plummeted; standards of literacy, sanitation and life expectancy have never been higher. The average European or American enjoys luxuries medieval potentates literally couldn’t have imagined. The essential finding of Steven Pinker’s 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature, a key reference text for the New Optimists, seems also to have been largely accepted: that we are living in history’s most peaceful era, with violence of all kinds – from deaths in war to schoolyard bullying – in steep decline.

But the New Optimists aren’t primarily interested in persuading us that human life involves a lot less suffering than it did a few hundred years ago. (Even if you’re a card-carrying pessimist, you probably didn’t need convincing of that fact.) Nestled inside that essentially indisputable claim, there are several more controversial implications. For example: that since things have so clearly been improving, we have good reason to assume they will continue to improve. And further – though this is a claim only sometimes made explicit in the work of the New Optimists – that whatever we’ve been doing these past decades, it’s clearly working, and so the political and economic arrangements that have brought us here are the ones we ought to stick with. Optimism, after all, means more than just believing that things aren’t as bad as you imagined: it means having justified confidence that they will be getting even better soon. “Rational optimism holds that the world will pull out of the current crisis,” Ridley wrote after the financial crisis of 2007-8, “because of the way that markets in goods, services and ideas allow human beings to exchange and specialise honestly for the betterment of all … I am a rational optimist: rational, because I have arrived at optimism not through temperament or instinct, but by looking at the evidence.”

If all this were really true, it would suggest that an overwhelming proportion of the energy we dedicate to debating the state of humanity – all the political outrage, the warnings of imminent disaster, the exasperated op-ed columns, all our anxiety and guilt about the misery afflicting people all over the world – is wasted. Or, worse, it might be counterproductive, insofar as a belief that things are irredeemably awful seems like a bad way to motivate people to make things better, and thus in danger of becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Here are the facts,” wrote the American economist Julian Simon, whose vocal opposition to the gloomy predictions of environmentalists and population experts in the 1970s and 1980s set the stage for today’s New Optimists. “On average, people throughout the world have been living longer and eating better than ever before. Fewer people die of famine nowadays than in earlier centuries … every single measure of material and environmental welfare in the United States has improved rather than deteriorated. This is also true of the world taken as a whole. All the long-run trends point in exactly the opposite direction from the projections of the doomsayers.”

Those are the facts. So why aren’t we all New Optimists now?

Optimists have been telling doom-mongers to cheer up since at least 1710, when the philosopher Gottfried Leibniz concluded that ours must be the best of all possible worlds, on the grounds that God, being perfect and merciful, would hardly have created one of the more mediocre ones instead. But the most recent outbreak of positivity may be best understood as a reaction to the pessimism triggered by the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. For one thing, those attacks were a textbook example of the kind of high-visibility bad news that activates our cognitive biases, convincing us that the world is becoming lethally dangerous when really it isn’t: in reality, a slightly higher number of Americans were killed while riding motorcycles in 2001 than died in the World Trade Center and on the hijacked planes.

But the New Optimism is also a rejoinder to the kind of introspection that gained pace in the west after 9/11, and subsequently the Iraq war – the feeling that, whether or not the new global insecurity was all our fault, it certainly demanded self-criticism and reflection, rather than simply a more strident assertion of the merits of our worldview. (“The whole world hates us, and we deserve it,” is how the French philosopher Pascal Bruckner derisively characterises this attitude.) On the contrary, the optimists insist, the data demonstrates that the global dominance of western power and ideas over the last two centuries has seen a transformative improvement in almost everyone’s quality of life. Matt Ridley likes to quote a predecessor of the contemporary optimists, the Whig historian Thomas Babington Macaulay: “On what principle is it that, when we see nothing but improvement behind us, we are to expect nothing but deterioration before us?”

The despondent self-criticism that frustrates the New Optimists is fuelled in part – at least the way they see it – by a kind of optical illusion in the way we think about progress. As Steven Pinker observes, whenever you’re busy judging governments or economic systems for falling short of standards of decency, it’s all too easy to lose sight of how those standards themselves have altered over time. We are scandalised by reports of prisoners being tortured by the CIA – but only thanks to the historically recent emergence of a general consensus that torture is beyond the pale. (In medieval England, it was a relatively unremarkable feature of the criminal justice system.) We can be appalled by the deaths of migrants in the Mediterranean only because we start from the position that unknown strangers from distant lands are worthy of moral consideration – a notion that would probably have struck most of us as absurd had we been born in 1700. Yet the stronger this kind of consensus grows, the more unconscionable each violation of it will seem. And so, ironically enough, the outrage you feel when you read the headlines is actually evidence that this is a magnificent time to be alive. (A recent addition to the New Optimist bookshelf, The Moral Arc by Michael Shermer, binds this argument directly to the optimists’ faith in science: it is scientific progress, he argues, that is destined to make us ever more ethical.)

The nagging suspicion that this argument is somehow based on a sleight of hand – it would seem to permit any outrage to be reinterpreted as evidence of our betterment – may lead you to another objection: even if it’s true that everything really is so much better than ever, why assume things will continue to improve? Improvements in sanitation and life expectancy can’t prevent rising sea levels destroying your country. And it’s dangerous, more generally, to predict future results by past performance: view things on a sufficiently long timescale, and it becomes impossible to tell whether the progress the New Optimists celebrate is evidence of history’s steady upward trajectory, or just a blip.

Almost every advance Norberg champions in his book Progress, for example, took place in the last 200 years – a fact that the optimists take as evidence of the unstoppable potency of modern civilisation, but which might just as easily be taken as evidence of how rare such periods of progress are. Humans have been around for 200,000 years; extrapolating from a 200-year stretch seems unwise. We risk making the mistake of the 19th-century British historian Henry Buckle, who confidently declared, in his book History of Civilization in England, that war would soon be a thing of the past. “That this barbarous pursuit is, in the progress of society, steadily declining, must be evident, even to the most hasty reader of European history,” he wrote. It was 1857; Buckle seemed confident that the recently concluded Crimean war would be one of the last.

But the real concern here is not that the steady progress of the last two centuries will gradually swing into reverse, plunging us back to the conditions of the past; it’s that the world we have created – the very engine of all that progress – is so complex, volatile and unpredictable that catastrophe might befall us at any moment. Steven Pinker may be absolutely correct that fewer and fewer people are resorting to violence to settle their disagreements, but (as he would concede) it only takes a single angry narcissist in possession of the nuclear codes to spark a global disaster. Digital technology has unquestionably helped fuel a worldwide surge in economic growth, but if cyberterrorists use it to bring down the planet’s financial infrastructure next month, that growth might rather swiftly become moot.

“The point is that if something does go seriously wrong in our societies, it’s really hard to see where it stops,” says David Runciman, professor of politics at Cambridge University, who takes a less sanguine view of the future, and who has debated New Optimists such as Ridley and Norberg. “The thought that, say, the next financial crisis, in a world as interconnected and algorithmically driven as our world, could simply spiral out of control – that is not an irrational thought. Which makes it quite hard to be blithely optimistic.” When you live in a world where everything seems to be getting better, yet it could all collapse tomorrow, “it’s perfectly rational to be freaked out.”

Runciman raises a related and equally troubling thought about modern politics, in his book The Confidence Trap. Democracy seems to be doing well: the New Optimists note that there are now about 120 democracies among the world’s 193 countries, up from just 40 in 1972. But what if it’s the very strength of democracy – and our complacency about its capacity to withstand almost anything – that augurs its eventual collapse? Could it be that our real problem is not an excess of pessimism, as the New Optimists maintain, but a dangerous degree of overconfidence?

According to this argument, the people who voted for Trump and Brexit didn’t really do so because they had concluded their system was broken, and needed to be replaced. On the contrary: they voted as they did precisely because they had grown too confident that the essential security provided by government would always be there for them, whatever incendiary choice they made at the ballot-box. People voted for Trump “because they didn’t believe him”, Runciman has written. They “wanted Trump to shake up a system that they also expected to shield them from the recklessness of a man like Trump”. The problem with this pattern – delivering electoral shocks because you’re confident the system can withstand them – is that there’s no reason to assume it can continue indefinitely: at some point, the damage may not be repairable. The New Optimists “describe a world in which human agency doesn’t seem to matter, because there are these evolved forces that are moving us in the right direction,” Runciman says. “But human agency does still matter … human beings still have the capacity to mess it all up. And it may be that our capacity to mess it up is growing.”

The optimists aren’t unaware of such risks – but it is a reliable feature of the optimistic mindset that one can usually find an upbeat interpretation of the same seemingly scary facts. “You’re asking, ‘Am I the man who falls out of a skyscraper, and as he passes the second storey, says, ‘So far, so good?’” Matt Ridley says. “And the answer is, well, actually, in the past, people have foreseen catastrophe just around the corner and been wrong about it so often that this a relevant fact to take into account.” History does seem to bear Ridley out. Then again, of course it does: if a civilisation-ending catastrophe had in fact occurred, you presumably wouldn’t be reading this now. People who predict imminent catastrophes are usually wrong. On the other hand, they need only be right once.

If there is a single moment that signalled the birth of the New Optimism, it was – fittingly, somehow – a TED talk, delivered in 2006 by the Swedish statistician and self-styled “edutainer” Hans Rosling, who died earlier this year. Entitled “The best stats you’ve ever seen”, Rosling’s talk summarised the results of an ingenious study he had conducted among Swedish university students. Presenting them with pairs of countries – Russia and Malaysia, Turkey and Sri Lanka, and so on – he asked them to guess which scored better on various measures of health, such as child mortality rates. The students reliably got it wrong, basing their answers on the assumption that countries closer to their own, both geographically and ethnically, must be better off.

But in fact Rosling had picked the pairs to prove a point: Russia had twice Malaysia’s child mortality, and Turkey twice that of Sri Lanka. Part of the defeatist mindset of the modern west, the way Rosling saw it, was the deeply ingrained assumption that we are living through times that are as good as they’re ever going to be – and that the future we are bequeathing, to future generations and especially to the world beyond Europe and north America, can only be a disheartening one. Rosling enjoyed observing that if you had run this experiment on chimpanzees by labelling a banana with the name of each country and inviting them to pick one, they would have performed better than the students, since they would be right half the time, thanks to chance. Well-educated European humans, by contrast, get things far wronger than chance. We are not merely ignorant of the facts; we are actively convinced of depressing “facts” that aren’t true.

It’s exhilarating to watch “The best stats you’ve ever seen” today – partly because of Rosling’s nerdy, high-energy stage performance, but also because it seems to shine the bracing light of objective fact on questions usually mired in angry partisanship. Far more than when he delivered the talk, we live now in the Age of the Take, in which a seemingly infinite supply of blog posts, opinion columns, books and TV talking heads compete to tell us how to feel about the news. Most of this opinionising focuses less on stacking up hard facts in favour of an argument than it does on declaring what attitude you ought to adopt: the typical take invites you to conclude, say, that Donald Trump is a fascist, or that he isn’t, or that BBC presenters are overpaid, or that your yoga practice is an instance of cultural appropriation. (This shouldn’t really come as a surprise: the internet economy is fuelled by attention, and it’s far easier to seize someone’s attention with emotionally charged argument than mere information – plus you don’t have to pay for the expensive reporting required to ferret out the facts.) The New Optimists promise something different: a way to feel about the state of the world based on the way it really is.

But after steeping yourself in their work, you begin to wonder if all their upbeat factoids really do speak for themselves. For a start, why assume that the correct comparison to be making is the one between the world as it was, say, 200 years ago, and the world as it is today? You might argue that comparing the present with the past is stacking the deck. Of course things are better than they were. But they’re surely nowhere near as good as they ought to be. To pick some obvious examples, humanity indisputably has the capacity to eliminate extreme poverty, end famines, or radically reduce human damage to the climate. But we’ve done none of these, and the fact that things aren’t as terrible as they were in 1800 is arguably beside the point.

Ironically, given their reliance on cognitive biases to explain our predilection for negativity, the New Optimists may be in the grip of one themselves: the “anchoring bias”, which describes our tendency to rely too heavily on certain pieces of information when making judgments. If you start from the fact that plague victims once languished in the streets of European cities, it’s natural to conclude that life these days is wonderful. But if you start from the position that we could have eliminated famines, or reversed global warming, the fact that such problems persist may provoke a different kind of judgment.

The argument that we should be feeling happier than we are because life on the planet as a whole is getting better, on average, also misunderstands a fundamental truth about how happiness works: our judgments of the world result from making specific comparisons that feel relevant to us, not on adopting what David Runciman refers to as “the view from outer space”. If people in your small American town are far less economically secure than they were in living memory, or if you’re a young British person facing the prospect that you might never own a home, it’s not particularly consoling to be told that more and more Chinese people are entering the middle classes. At book readings in the US midwest, Ridley recalls, audience members frequently questioned his optimism on the grounds that their own lives didn’t seem to be on an upward trajectory. “They’d say, ‘You keep saying the world’s getting better, but it doesn’t feel like that round here.’ And I would say, ‘Yes, but this isn’t the whole world! Are you not even a little bit cheered by the fact that really poor Africans are getting a bit less poor?’” There is a sense in which this is a fair point. But there’s another sense in which it’s a completely irrelevant one.

At its heart, the New Optimism is an ideological argument: broadly speaking, its proponents are advocates for the power of free markets, and they intend their sunny picture of humanity’s recent past and imminent future to vindicate their politics. This is a perfectly legitimate political argument to make – but it’s still a political argument, not a straightforward, neutral reliance on objective facts. The claim that we are living in a golden age, and that our dominant mood of pessimism is unwarranted, is not an antidote to the Age of the Take, but a Take like any other – and it makes just as much sense to adopt the opposite view. “What I dislike,” Runciman says, “is this assumption that if you push back against their argument, what you’re saying is that all these things are not worth valuing … For people to feel deeply uneasy about the world we inhabit now, despite all these indicators pointing up, seems to me reasonable, given the relative instability of the evidence of this progress, and the [unpredictability] that overhangs it. Everything really is pretty fragile.”

Johan Norberg, who launched his book Progress two months before the US presidential election, watched the results come in on a foggy morning in Stockholm, at a party organised by the American embassy. As Trump’s victory became a certainty, the atmosphere turned from one of rumbling alarm to horrified disbelief. “We were all Swedes in the media, politics, business and so on – I think it would have been hard to find a single person there who had hoped for a Trump win – so pretty soon the mood was going downhill dramatically,” Norberg recalled. “And what’s more, they didn’t have any alcohol, which didn’t help, because everyone was saying: ‘We need something strong here!’ But they had it more set up like a breakfast thing.” He smiled. “I think Americans don’t really understand Swedes.”

The populist surges of the last two years in the US and Britain – powering the rise of Trump, the Brexit vote, and the unpredicted levels of support for Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn – pose a complicated problem for the New Optimists. On the one hand, it’s easy enough to characterise such anger directed toward political establishments as a mistake, based on a failure to perceive how well things are going; or as a legitimate reaction to real, but localised and temporary bumps in the road, which needn’t constitute any larger argument for pessimism. On the other hand, it is a curious view of the world that sees such political waves solely as responses, mistaken or otherwise, to the real situation. They are part of that real situation. Even if you think that Trump supporters, say, were wholly in error to perceive their situation negatively, the perception itself was real enough – and they really did elect Trump, with all his potential for destabilisation. (The New Optimists, says David Runciman, think of politics as nothing more than an annoyance, because in their view “the things that drive progress are not political. But the things that drive failure are political.”) There is a point at which it stops being so relevant whether widespread pessimism and anxiety can be justified or not, and becomes more relevant simply that it is widespread.

Norberg is no Trump supporter, and the election result might have seemed like a setback to an author promoting a book painting humanity’s immediate future as entirely rosy. In it, he does warn that progress isn’t inevitable: “There is a real risk of a nativist backlash,” he writes. “When we don’t see the progress we have made, we begin to search for scapegoats for the problems that remain.” But it is in the nature of the New Optimism that negative developments can be alchemised into reasons to be cheerful, and by the time we spoke, Norberg had an upbeat spin on the election, too.

“I think it might be that in a couple of years’ time, we’ll think it was a great thing that Trump won,” he says. “Because if he’d lost, and Hillary had won, she’d have been the most hated president of modern times, and then Trump and Bannon would have used that to build an alt-right media empire, create an avalanche of hatred, and then there might have been a more disciplined candidate the next time round – a real fascist, rather than someone impersonating … Trump may prove to have been the incompetent, self-absorbed person who ruins the populist brand in the United States.” This sort of counterfactual argument suffers from not being falsifiable, and in any case, it’s a long way from a position of straightforward positivity about the direction in which the world is moving. But perhaps it is the one genuinely indisputable truth on which the New Optimists and the more pessimistically minded can agree: that whatever happens, things could always, in principle, have been worse.