This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

On a recent Monday morning, Joe Piscopo — “former Saturday Night Live superstar” — used his AM-radio show to decry the plight of Italian Americans. City officials in Newark, New Jersey, had just taken down a statue of Christopher Columbus, and Piscopo feared other effigies of the Italian explorer might be under threat. “If these creepy losers, these thugs, go near that statue in Columbus Circle, we will mobilize,” he vowed. Then he welcomed his next guest, who picked up where Piscopo left off without missing a beat.

“I was just listening to you talk about the Columbus statue and the attack on the Italian Americans, and you’re 100 percent correct,” said Ed Mullins, president of the Sergeants Benevolent Association, which represents nearly 5,000 officers of the NYPD. “We’re wiping away our history, and we’re painting Black Lives Matter signs in the streets.” As a regular on the conservative-media circuit, Mullins has perfected the art of playing directly to the fears of older white voters. “What they’re attacking is the fiber for what we believe in. They’re attacking law and order and authority. When they get past us, Joe, they will be in your studio taking control of the message. They will be in people’s homes taking control of their homes, running the subways, not letting children play in parks. The silent majority cannot sit by and be silent.”

When they get past us. Mullins didn’t say who “they” were, but it was clear whom he meant by “us”: the brave men and women of the NYPD. The city’s 36,000 police officers are represented by five different unions, each covering a specific rank — patrol, detective, sergeant, lieutenant, and captain. The SBA is relatively small compared with the Police Benevolent Association, which has 24,000 dues-paying members, making it the country’s largest municipal police union. Patrick Lynch, the president of the PBA, has played the most high-profile role in combating attempts by lawmakers and activists to curtail police abuses, often in brash, hyperbolic sound bites. “We have a progressive mayor that’s anti-police, the City Council that’s anti-police, and the statehouse is anti-police,” Lynch recently complained to President Trump. “They’re changing the law, where it’s becoming impossible to do our job.”

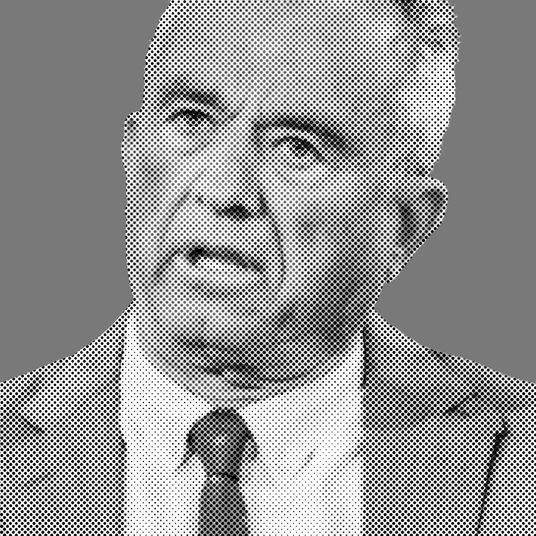

But talk to anyone familiar with New York law enforcement — from NYPD brass to city and state lawmakers — and they will tell you that, compared with Mullins, Lynch is a genteel statesman. Whatever his union lacks in size, Mullins makes up for in maximalist rhetoric. Over the past nine months alone, he has called Mayor de Blasio a liar, a disgrace, and “full of shit.” He declared war on the mayor on behalf of the entire NYPD and used the union’s Twitter account to dox de Blasio’s daughter, calling her a “rioting anarchist.” Mullins claimed that by enacting bail reform, Governor Cuomo was “holding down the hands of a victim while they’re being raped.” He denounced high-ranking police officers as “whores” for kneeling with protesters, and he called Dr. Oxiris Barbot, then the city’s health commissioner, a “bitch.” When I asked him, recently, how his members were served by such vulgar remarks, Mullins insisted that his approach is no different than tweeting the phrase black lives matter. “It draws attention,” he said.

During his nearly two decades as president of the SBA, Mullins has used that attention to fend off virtually every attempt, no matter how modest, to curb police brutality and corruption. In his view, police are not above the law. Rather, the law should empower police to operate however they choose, almost entirely free of oversight or consequence. If the pace of police reform seems glacial, even in the wake of the global uprisings over the death of George Floyd, that’s because Mullins has helped push the outer edge of the debate so far to the right that even the smallest compromise seems unthinkable. In 2003, he suggested cops should be allowed to sue the estates of people they shoot for emotional damages. In 2006, he demanded Mayor Bloomberg apologize for saying he was “deeply disturbed” that police shot Sean Bell, an unarmed Black man, 50 times. He has fought against mandatory Breathalyzer tests for cops who fire their weapons on duty and defended an officer who was caught on video smashing a handcuffed 14-year-old through a window. The union has deployed its lawyers to protect sergeants accused of sexual harassment, racism, manslaughter, fudging crime complaints, and drunkenly shooting up an ATM. In 2017, when Brooklyn College asked NYPD officers in need of a bathroom break to respect the wishes of students by steering clear of most restrooms on campus, the SBA hinted darkly about the threat of active shooters and terrorists. “Maybe,” the union tweeted, “it’s time people get what they ask for.”

Name-calling and threats aside, much of Mullins’s power comes from his longevity — and his ability to cause trouble for his superiors. “He has been a thorn in the side of four commissioners,” says Bill Bratton, who served as police commissioner under de Blasio and Rudy Giuliani. “He has always been a pain in the ass.” Mullins also enjoys fierce loyalty from the rank and file, who love his zealous, uninhibited defense of cops. As one sergeant described it to me, “Mullins speaks the truth.” By staying on the offensive, this leader of a small, little-known labor union has forged an outsize role in the national debate over the use and overuse of force by law-enforcement officers. Patrick Lynch, who has the hair and temperament of a college-basketball coach, may be the face of police defiance, but Ed Mullins is its angriest and most unfiltered voice.

“Mullins is a wartime leader,” an anonymous poster wrote recently on Law Enforcement Rant, a popular message board where current and former NYPD officers go to vent, often in explicitly racist terms. “He has a backbone of steel. God bless you, Sarge, I’d follow you anywhere.”

I’m a patriot,” Mullins told me, minutes after his appearance on Piscopo’s show. “I’m basically for people enjoying their lives. I don’t care what the color of their skin is.”

Mullins was sitting behind his desk in the union’s headquarters in Tribeca. Like roughly a quarter of all NYPD officers, he drives into work each day from his home on Long Island. He hadn’t put on his tie yet, and, like the other SBA officials milling around the office, he wasn’t wearing a mask. He was, however, wearing a gun on his belt. The union’s bylaws require its president be a police officer, which means Mullins, though he works full-time as a labor boss, is still a sergeant in the NYPD. In 2018, he was paid $130,542 by the city and $86,818 by the union.

For half a century, police unions were the rare labor organizations that enjoyed the favor of both union-loving Democrats and law-and-order Republicans. Now, as calls mount to “defund the police,” unions like the SBA are facing an unprecedented level of criticism and scrutiny. “More and more of the public is becoming educated about what a destructive role the unions have played,” says Joo-Hyun Kang, director of Communities United for Police Reform.

But if Mullins is worried about his union’s future, he doesn’t show it. In person, he is jarringly friendly and polite, his New York accent softened by his drowsy cadence. “I know that the newspapers try to label me a racist,” he told me. “But it’s totally indefensible. They don’t know me. They don’t know where I come from, my background. They really have no clue what I do in my own life. And it doesn’t bother me at all.”

Mullins was raised in a very different era in the racial politics of New York. Born in 1962, he grew up with three siblings in an apartment in Greenwich Village, the son of a longshoreman who worked the West Side docks. His father wasn’t an active union man, but Mullins describes him as “the pope of Greenwich Village,” a guy who knew every family and shopkeeper in their small corner of Manhattan. Back then, the Village was an almost entirely white neighborhood in a deeply segregated city. But Mullins remembers the time wistfully as a model of racial harmony. “You had different races and different ethnic backgrounds in all different areas of the city, but everybody got along; everybody had respect for each other,” he says. “Most of the people I grew up with, their parents were laborers. If a criminal came into the neighborhood, it was the criminal against the neighborhood.”

After briefly considering enlisting in the Marines, Mullins joined the NYPD in 1982 and was assigned to the 13th Precinct in Gramercy Park. It was a tumultuous period in the city’s history — “the bad old days,” as Mullins puts it. The NYPD was reeling from budget cuts, the crack epidemic raged, homicide was on the rise, and whites were fleeing the city. Two years after Mullins became an officer, a cop shot and killed Eleanor Bumpurs, an elderly Black woman with a history of mental illness, while trying to evict her from her Bronx apartment. Two months later, Bernhard Goetz was hailed as a hero after he shot four Black teenagers who allegedly tried to rob him on the subway. In 1986, a white mob in Howard Beach killed a young Black man who wandered into the neighborhood after his car broke down.

When it came to racial tensions, the police unions were no small part of the problem. Initially formed as “benevolent associations” to support the widows and orphans of slain officers, they weren’t formally recognized as unions until 1967 — and their us-versus-them mindset was forged during the turbulence of that decade as they pushed back aggressively against civil-rights activists, Vietnam War protesters, and reformers bent on rooting out misconduct, bribery, and corruption in the NYPD. “Police officers were angry,” says Samuel Walker, an expert in police accountability and professor emeritus at the University of Nebraska School of Criminology and Criminal Justice. “In many ways, police officers mimicked the behavior of their opponents in the civil-rights movement. You’re feeling deceived and oppressed? You organize; you fight back.”

At the same time, the unions found creative ways to exert their influence in Albany, even though they were forbidden to strike. “The answer lies in obtaining political and economic ‘clout,’ ” explained Harold Melnick, the first president of the modern-day SBA. Much of that clout came from appealing to white law-and-order voters. In 1966, in an effort to stir up opposition to a proposed review board that would have given civilians greater oversight of the police, the PBA produced a TV ad depicting a white woman leaving a subway station alone. “The Civilian Review Board must be stopped,” a voice intoned. “Her life — your life — may depend on it.” In 1975, when the NYPD faced massive layoffs, the PBA distributed a pamphlet with a now-infamous message: WELCOME TO FEAR CITY.

As a young cop and aspiring union leader, Mullins closely observed the tactics of his predecessors who had earned their stripes during the ’60s. At the time of the Bumpurs shooting, Mullins had just been elected PBA delegate for the 13th Precinct. He was inspired by the union’s president, Phil Caruso, whose skill at negotiating big raises and shooting down reforms turned the PBA into a “powerful, wired institution that stands virtually beyond scrutiny,” as The Village Voice put it. Caruso went on the offensive in the Bumpurs case, organizing a rally of more than 5,000 officers — Mullins among them — outside the Bronx courthouse where the cop who’d shot Bumpurs was being tried for second-degree manslaughter. The officer was acquitted.

Mullins recalled the lessons from that case in 2016, when an NYPD sergeant named Hugh Barry was called to the apartment of Deborah Danner, another elderly Black woman with a history of mental illness. When Danner swung a baseball bat at Barry, the sergeant shot and killed her. A grand jury indicted Barry on murder, manslaughter, and negligent homicide. Mullins sprang into action. “People don’t even understand the work that I put into that case, the money that we spent on that case,” he told me. “I called up people who’d worked on the Bumpurs case, and I asked a lot of questions: How did they approach it? What did they do? What would you do different? What should I be looking for?” The veterans told Mullins that the Bumpurs shooting had been “a mess of a media thing” and encouraged him to focus on controlling the narrative. Mullins took the advice, publicly blaming the mayor and police commissioner for comments that he claimed had prejudiced the grand jury. It was “politics,” he insisted, that led to the indictment. Barry was acquitted.

Mullins thinks people unfairly accuse police unions of defending heinous behavior. In his view, he’s only doing what any labor leader would in his position: zealously protecting his members. “People have to look at police unions as other unions,” he says. “We have the right to protect our workplace environment just like longshoremen, airline workers, and everyone else. When a schoolteacher gets accused of molesting a child, we don’t attack the United Federation of Teachers.” But the police union goes far beyond defending the bounds of its contract. A teachers union may fight to ensure that alleged child molesters receive a fair disciplinary hearing, but it doesn’t provide them with criminal-defense lawyers — and it certainly doesn’t lobby against laws to fire and imprison teachers who molest students.

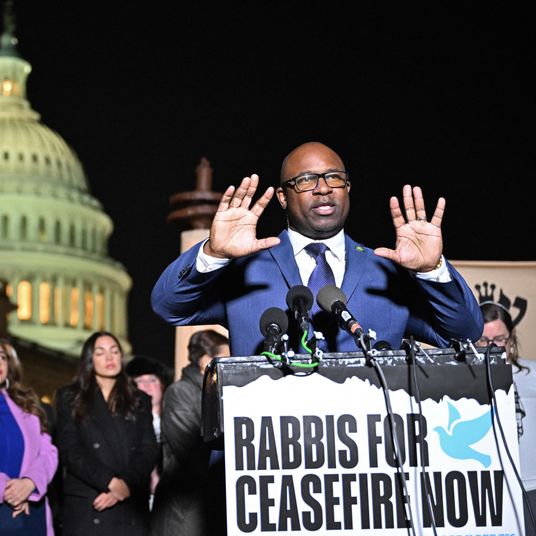

There’s no question that police unions have been on the defensive since the killing of George Floyd. They have been shunned by fellow labor unions and criticized by everyone from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to officers in their own ranks. Last year, the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative think tank, concluded that police unions have come to represent “party and political ideologies” rather than employees. Facing increased pressure to reform the police, lawmakers in Albany have begun to rethink their allegiance to unions like the SBA. “For years, the Senate was a wholly owned subsidiary of the District Attorneys Association and the police unions. Anything that they opposed was killed in the Senate,” says State Assemblymember Danny O’Donnell. “But they don’t really have that power anymore.”

In June, the assembly passed a bill sponsored by O’Donnell to repeal 50-a, a law that had long shielded officer-misconduct records from the public. Lawmakers also banned choke holds like the one used to kill Eric Garner, strengthened the attorney general’s mandate to investigate police killings, and required the state to collect detailed information on arrests and the use of force. At the same time, Police Commissioner Dermot Shea disbanded the NYPD’s plainclothes anti-crime units, which were involved in disproportionately more fatal shootings than uniformed units, and the city made deep cuts to the NYPD’s annual budget of $6 billion.

Mullins admits that police unions have lost some power, but he insists that the SBA has never stood in the way of reform. His complaint with the latest batch of reforms is that the police unions were not consulted. He made the same argument about stop and frisk, claiming the unions did not have a seat at the table when police came under fire for using the policy to target people of color. But when Mullins was named to a 17-person committee tasked with advising a federal mediator on stop and frisk, he failed to show up to a single meeting. And if the SBA wasn’t consulted on 50-a, it may be because the union has made every effort over the past decade to block its repeal.

While lieutenants and captains generally sit behind desks and push papers, sergeants are out on the front lines every day. They patrol the streets alongside the dozen or more officers they supervise, making them directly responsible for implementing the policies passed down from 1 Police Plaza and City Hall. Mullins doesn’t consider himself a “super-union” guy, but back when he was promoted to sergeant in the mid-’90s, he felt the SBA was failing its members on boilerplate issues. The union hadn’t negotiated decent raises with the city, prescription co-pays were 30 percent, and the leadership’s attitude, according to Mullins, was “Be happy with what you got.”

In March 2000, as Mullins was laying the groundwork to run for union president, he was involved in a shoot-out in East Brooklyn. He didn’t hit anyone, but whenever officers fire their weapons, they require union representation. That night, it took more than five hours for an SBA delegate to arrive at the precinct. Mullins is convinced the delay was punishment for his campaign. Still, when the election was held in 2002, he won handily.

Since then, he has negotiated four contracts that have boosted sergeants’ pay by more than 40 percent. SBA members now have no co-pay on generic prescriptions, and union lawyers are available to represent them at the drop of a hat, day or night. Mullins also isn’t afraid to go to court: The SBA has sued the city repeatedly, winning at least $28 million for its members.

Like the SBA, the other four unions representing the NYPD are led by white men — a lack of diversity that doesn’t sit well with many officers of color. “The unions have made almost no effort to acknowledge that they have a diversity problem,” says Philip Banks, the first Black officer to serve as chief of department, the NYPD’s highest uniformed position. “Black officers often feel alienated by their us-versus-them rhetoric, because are we us or are we them?”

Mullins insists he has been “on the forefront” of efforts to diversify union leadership. Three of the SBA’s board members are African American, and the union was the first to have a woman on its executive board. (“Unfortunately for us,” Mullins says, “she retired.”) But he downplays the very notion of racial divisions among officers. “Our membership, although diverse, is pretty solid,” he says, “in the sense that everybody’s blue.”

Under Mullins, the SBA’s culture hasn’t exactly been a model of racial sensitivity. The union dismissed police brutality in Ferguson, Missouri — which ignited the Black Lives Matter movement — as a “lie.” It called Darcel Clark, the first Black female district attorney in New York, “stupid.” Mullins once sent a video to his entire membership — hailing it as “the best video I’ve ever seen” — that referred to Black people as “monsters” and “welfare queens.” Mullins later apologized, claiming he hadn’t watched the video in full before sending it out. “I have Black friends,” he told Gothamist in his defense.

Mullins’s rhetoric escalated dramatically in 2014, when NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo was videotaped placing Eric Garner in a lethal choke hold. Ever since, Mullins has been engaged in an all-out war with Black Lives Matter, concentrating most of his ire on Mayor de Blasio. A month after Garner’s death, the SBA paid for full-page ads in the New York Post and the New York Times discouraging the Democratic National Committee from holding its convention in New York and accusing the city of “lurching backwards to the bad old days of high crime, danger-infested public spaces, and families that walk our streets worried for their safety.” When de Blasio told reporters that he and his wife had trained their Black son for the “dangers” he might face when encountering police, Mullins went ballistic, calling the mayor “moronic.” Two weeks later, after two NYPD officers were gunned down while sitting in their patrol car, Mullins accused de Blasio of having blood on his hands. Both the SBA and the PBA instructed their members to literally turn their backs on the mayor in public.

The union’s full-fledged attack on the mayor is remarkable given how little he has done to actually challenge the NYPD. It was de Blasio, after all, who increased the department’s budget, supported the use of 50-a to shield police misconduct from public scrutiny, and brought back Bill Bratton, who was well liked by the rank and file. “Cops wanted searchlights on the front of their cars and flashlights on their gun belts, and we did it,” says Peter Donald, who served as assistant police commissioner from 2016 to 2019. “When the Dallas shooting happened, Bratton, in basically 24 hours, figured out what new vests were going to cost and put two heavy vests and helmets in the back of every patrol car. That sort of stuff wouldn’t have been possible without de Blasio.”

As the war of words between Mullins and the mayor has escalated, shootings in the city have increased by 72 percent this year. The unions lay the blame on an “anti-police atmosphere” and a host of reforms, including the release of some 1,500 defendants from Rikers because of concerns about the coronavirus. (Confidential police data obtained by the Times found no link between the releases and the spike in shootings.) Others — including retired NYPD officer and Brooklyn borough president Eric Adams — question whether the unions are staging a “blue flu,” encouraging their members to call in sick and otherwise engage in an illegal slowdown of arrests and investigations.

In the past, Mullins has not been shy about calling for unofficial slowdowns. “If there’s a delay in getting to the next place, so be it,” he told his members in August 2014, after Eric Garner was killed. Traffic tickets plunged by 94 percent, a huge financial loss to the city. Last September, after Pantaleo was fired for killing Garner, there was another slowdown. But in recent weeks, union leaders have not hinted at a blue flu, and Mullins insists there has been no slowdown. Politicians like Adams, he says, should stop questioning the work ethic of police officers and start focusing on “Black-on-Black crime.”

If anything has kept police off the street, it’s COVID-19. At least 30 officers have been killed by the virus, which forced nearly 20 percent of the entire NYPD — almost 7,000 uniformed officers — to call in sick in April. Yet Mullins refuses to wear a mask, even in large crowds, an expression of his defiance of de Blasio and of his skepticism of all the media attention being devoted to the coronavirus. “I’m really beginning to question if there’s an underlying motive to this,” says Mullins, who has taken to doing interviews with a QAnon mug prominently displayed next to an American flag.

Mullins is halfway through his final full term as union president. In 2025, he’ll be 63, the NYPD’s mandatory retirement age. When I asked him if he would ever consider running for office, he seemed to light up. “A lot of people want me to, to be honest. I get begged all the time,” Mullins said. “I’ve been asked to run for Senate, asked to run for Congress, asked to run for mayor.” He claims to be in regular contact with the White House, providing advice on issues of law enforcement. Since the earliest days of his campaign, Trump has dramatically amplified the us-versus-them narrative pushed by union leaders like Mullins. The president has denounced Black Lives Matter as “a symbol of hate” and accused the movement of “calling death to police.” Sometimes Mullins’s language aligns so closely with Trump’s that it’s hard to tell the two apart. “How beautiful,” the SBA tweeted after a man was videotaped yelling at a group of cops earlier this year, “if just one day people like this meet the wrong cop and get a good old fashion ass whipping.”

Mullins is starting to come under scrutiny for his incendiary language. In February, the NYPD launched an investigation into his history of offensive remarks. And in June, spurred by his release of confidential information about the mayor’s daughter, the City Council asked the department to turn over Mullins’s disciplinary records — the first such request since the repeal of 50-a. “We wouldn’t tolerate this kind of behavior from any other city employees, and we should not tolerate it from police-union leaders,” said City Council Speaker Corey Johnson. “We need to hold them accountable.”

Mullins understands that standards for police behavior shift over time. In 1987, a few years after Mullins joined the force, a 35-year-old transit worker named Wajid Abdul-Salaam was found dead in a holding cell two hours after being arrested for attempted burglary. Abdul-Salaam had been hog-tied, his limbs trussed with cuffs and shackles behind his back. Within days, the police commissioner announced he was banning the practice of hog-tying. Caruso, Mullins’s hero at the PBA, adamantly opposed the ban, claiming it undermined officers’ ability to do their jobs, and the union filed a lawsuit to defend the practice.

Today Mullins agrees that people should not be hog-tied, but he doesn’t fault Caruso for not seeing that. “I understand the methodology behind where Phil was coming from at the time,” he says. “Today we’re talking about choke holds, and back then we were talking about hog-tying. Phil realized what occurred in the street — people would literally kick out windows of patrol vehicles. So I could see him take that position. But here we are, probably 30 years later, and the ban really had no impact on policing.”

Earlier this month, the SBA joined 17 other police unions to sue the city in an effort to block the Eric Garner Anti-Chokehold Act. I asked Mullins if Caruso’s stance on hog-tying has made him rethink the use of choke holds. Mullins said he’s open to a ban, but then immediately launched into a defense of the tactic and the officer who killed Garner. “I don’t believe that Pantaleo did anything wrong,” he said. “I believe that the circumstances were bad, and it just ended tragically.”

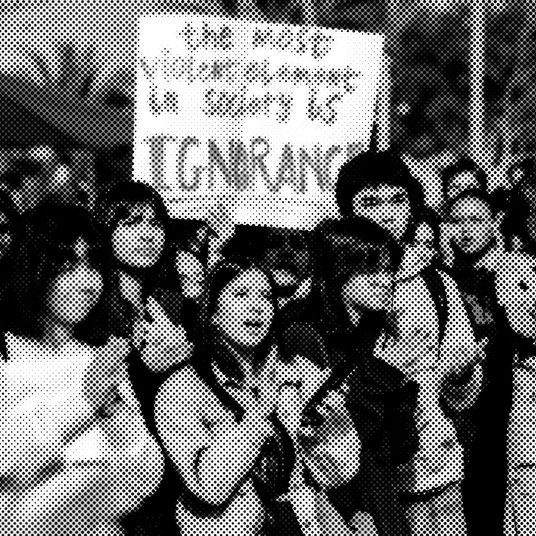

On a sunny Wednesday morning in mid-July, hundreds of demonstrators gathered in Cadman Plaza and prepared to march across the Brooklyn Bridge. The marchers, mostly clergy, their congregants, and community leaders from predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods, were there for a day of prayer and unity — to ask God, and lawmakers, to address a series of issues listed on the T-shirts they wore: education reform, housing reform, health-care reform, police reform.

As marchers filed into the plaza, some were surprised to see more than 100 off-duty and retired members of the SBA preparing to join them. “I thought maybe they were trying to put their best foot forward,” recalls Kimberly McLaurin, a community organizer who had helped plan the event. McLaurin knew that a clergy member had invited Mullins and the SBA to march, but she hadn’t expected so many cops to actually show up. “I don’t feel like all police officers are bad,” she says. “It gave me a feeling of hope to see them there.”

What McLaurin didn’t know was that the SBA had been promoting the event as a march “to support law enforcement.” That morning, in response, police-brutality protesters showed up before the march began and linked arms to stop it from crossing the bridge. NYPD officers charged the group and demanded they disperse. Out of sight of the prayer marchers, three officers were injured and 36 protesters arrested.

“I had a friend call and ask if I was okay,” says Tramell Thompson, one of the prayer marchers. “She said protesters were getting locked up. I said, ‘I’m with the church. Why would I be getting locked up?’ Then I realized — Oh, this became a Blue Lives Matter march all because the SBA decided to have their own narrative. I was so angry.”

After the scuffle was over, Thompson and the other prayer marchers began ascending the bridge. Dressed in white T-shirts, they sang church hymns through their masks, unaware of the violence that had unfolded moments earlier. Members of the SBA, wearing blue T-shirts and few masks, unfurled signs that read BLUE LIVES MATTER, SUPPORT THE NYPD, and WE NEED ANOTHER CRIME BILL.

“This is akin to what I envision the Selma march to be like,” a white member of the SBA said as he made his way up the bridge — an unintentionally apt comparison, given the violence that preceded the morning’s event. “It’s just an extremely powerful moment of people that are viewed as opposites coming together.”

For McLaurin, though, there was only deceit. “The SBA used our numbers to make it seem like they had more support from the Black community than they do,” she says. “They hijacked the message. What Mullins did was disgusting. If anything, it caused more division between the community and the police department.”

Mullins took full advantage of the situation. Only hours after the march, he appeared on Newsmax, the conservative cable outlet, to tout the event as a show of support for the police by “the clergy members of the African American and Latino community.” Those communities, he added, “want the police” — unlike Black Lives Matter, which “has done nothing for the Black community, nothing to help society.”

It was a decidedly different tone than the one he had struck earlier in the day as he marched across the bridge. Dressed in jeans and a black polo shirt emblazoned with the SBA shield, Mullins embraced members of the clergy, even though he wasn’t wearing a mask. To all appearances, he was siding with those who were calling for the very kind of police reform he has spent his entire career fighting.

As the prayer marchers reached the top of the bridge, leaders at the front struck up a chant: “Unity! Unity! Unity!” Mullins suddenly seemed uncomfortable, hesitant to chant along. Then, for a brief moment, he quietly joined in.

“Unity,” he repeated softly, as if trying out the word.

*This article appears in the August 17, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!