Financial Journeys and COVID-19

Mapping the financial journeys of refugees and asylum seekers in Jordan, and the impact of COVID-19 on the economic lives of refugees in Nairobi.

Welcome to our first FIND (Finance in Displacement) newsletter. Every month we will bring you updates from our field sites about how displaced people are adapting to their economic and financial surroundings. Each time, we will spotlight one of our focus sites, either Kenya or Jordan, and add in observations from other sites in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, the US and Germany. We will also feature relevant policy work. Our research and policy team includes professionals from Katholischen Universität Eichstätt – Ingolstadt (Catholic University or KU), Tufts University, the International Rescue Committee, and GIZ. In this newsletter, we feature research in Jordan overseen by Swati Mehta Dhawan, Research Associate at KU, and Dr. Hans-Martin Zademach, Professor of Economic Geography at KU.

This month…

- What we learnt looking at “financial journeys” of 89 refugees in Jordan?

- Financial phases among Nairobi’s refugees

- FIND research informs IRC report on livelihoods in Jordan and Lebanon

- Financial inclusion and resilience for FDPs in the time of COVID-19

What we learnt looking at “financial journeys” of 89 refugees in Jordan?

By Swati Mehta Dhawan

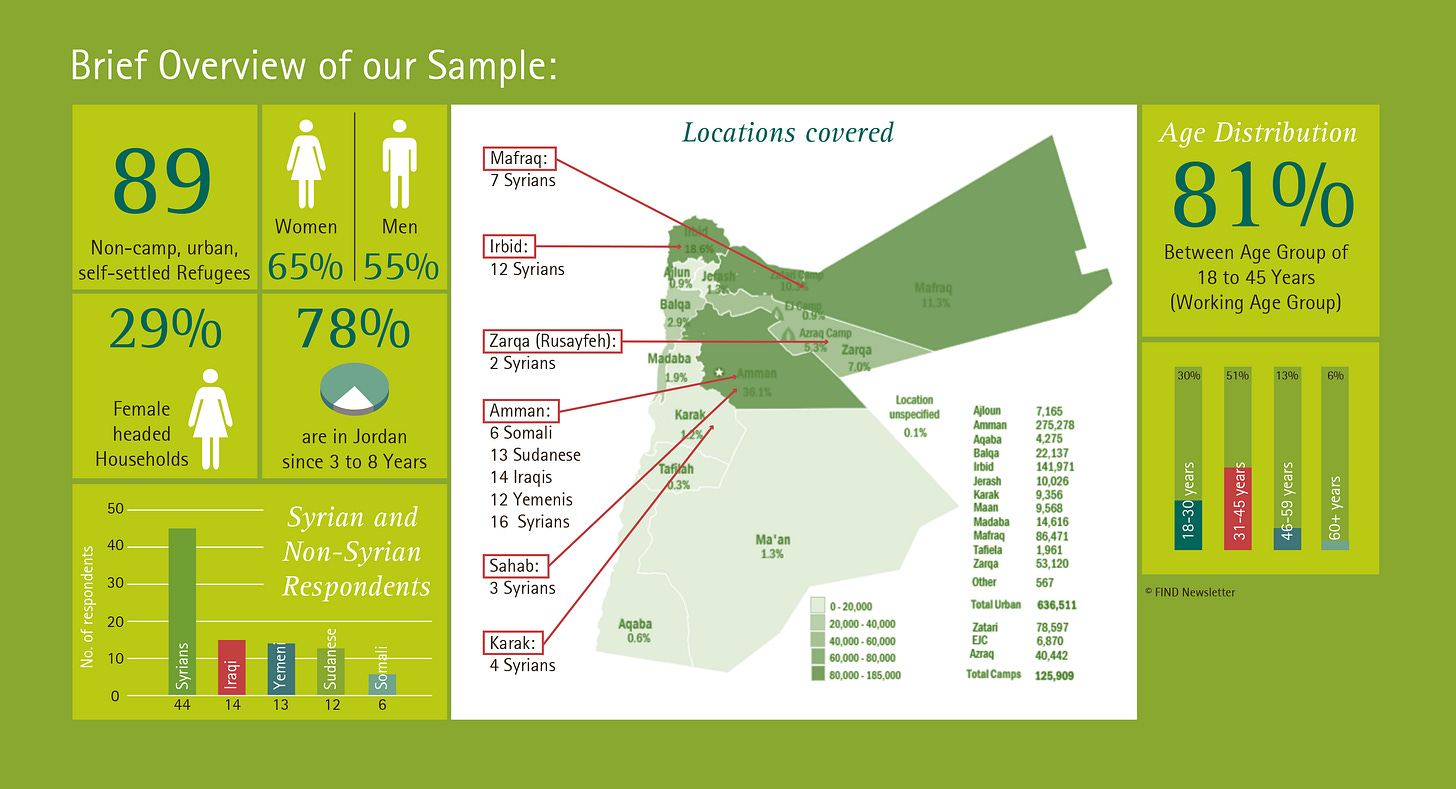

Over the course of last nine months, we have completed two intensive rounds of in-depth interviews with 89 refugees and asylum seekers in Jordan (see more on sample at the end and more about the project here). These interviews have tried to capture the strategies that respondents used to perform the various financial tasks during different stages of displacement, especially after they arrived in Jordan. The interviews probed financial stressors, coping strategies, household financial management, and access to and use of financial services.

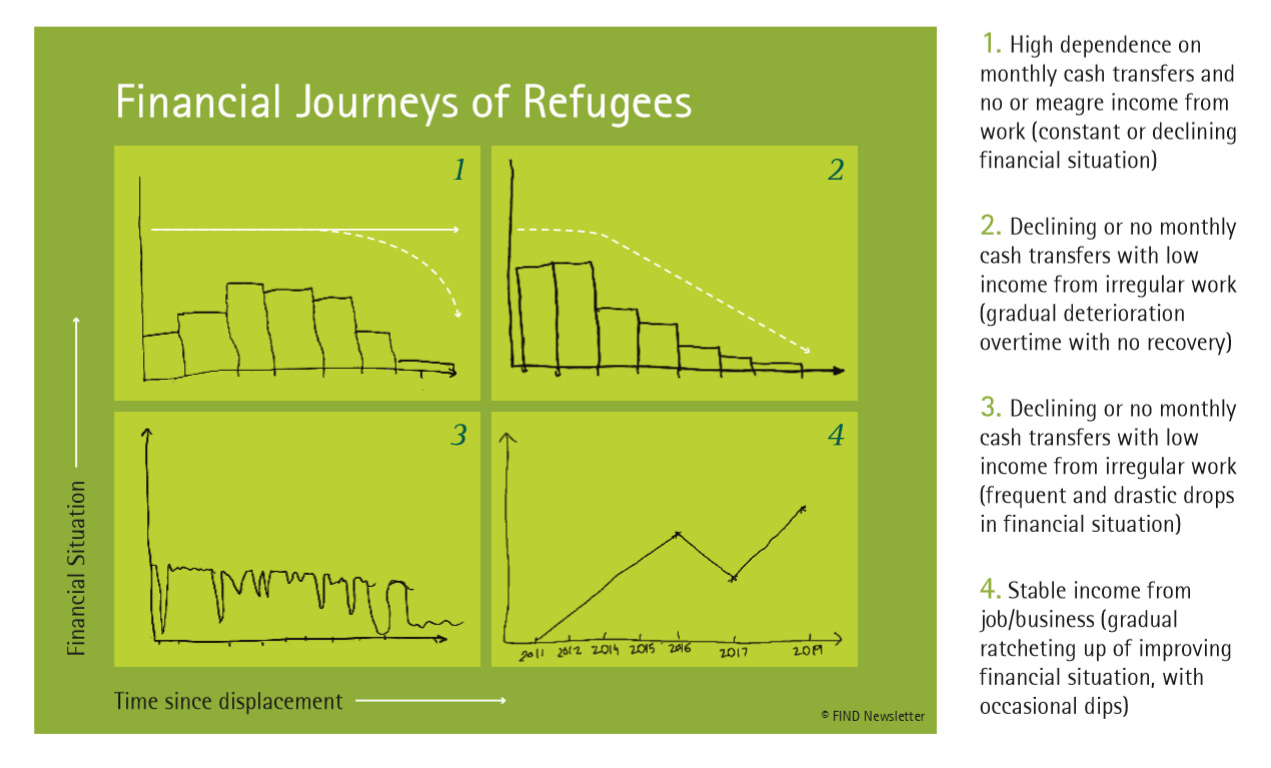

The most impactful exercise that we did with research respondents was to map their financial journeys since they arrived in Jordan. We asked them to plot their financial ups and downs on a graph (see examples below), with the two axes representing the time since their displacement and their corresponding financial situation. Referring to their graphs we then discussed their livelihood stories, financial challenges, and coping strategies with the purpose of understanding the factors that constrained or enabled their financial outcomes.

While each respondent’s journey and their challenges are unique, if we zoom out, we can see that four types of journeys are most common. Note that there are differences based on gender, household size, nationality, and strength of social networks.

Cases 1, 2, and 3 belong to the majority who are stuck in what we can call “survivelihood phase”, where they find menial work that provides a meagre pay which has to be supplemented by handouts (from humanitarian organisations or private donors) and borrowings from their friends and families.

For most, this phase has lasted for more than just the initial stage upon arrival. They face difficulties in finding stable jobs or starting businesses, and experience rising costs of living, increasing family size, rising childcare expenses, and health expenses. Sometimes there are incremental gains with a better job or some aid, and they might be able to meet their financial needs, pay off their debts, and even save a little extra. However, these are not sustainable as jobs remain unstable and in the event of an external shock those gains are lost. Many respondents said how 2019 had been a difficult year for them and now they see things going from bad to worse. We are yet to study the impact of COVID-19 on this situation (data collected in May-June 2020).

“Seriously, we don’t know where the money goes. I hate the end and beginning of the month, the first 10 days of the month, I hate them. It is all about repaying debt, rent, and bills. The moment we get the money, nothing is left.” – Female (head of HH), 36 year old, Syrian, Amman

Case 4 shows “positive deviance”, where we see a gradual ratcheting up of livelihoods. Overtime, these respondents found better paying jobs, started profitable businesses, improved their professional capacities, and leveraged their strong social networks. However, as we see in the graph even for them there could be dips, as they face legal issues or losses in their business, or job loss.

“Even though it looks like I am doing well, but I don’t feel any sense of stability. There is no stability here, we were used to owning property in Syria, but here we have to pay rent. If the business doesn’t go well for a day or two, I am in trouble. I am always stressed out” – Male, 36 year old, Syrian, Irbid

In the upcoming newsletters we will take up individual respondent stories to better paint the picture and provide insights to feed into policy and programming to support their ratcheting up process. Insights will include how they manage their finances, how they earn a living, the role of cash assistance, their financial service needs, behavioural insights, and specific insights on gender.

For now, we will leave you with more quotes from our respondents which can describe their experiences and perspectives better than any words that I might use. Also see a quick summary of the sample at the end.

Voices from the field

On integration:

“I’m mingling with everyone, the good ones and the bad ones, but when it comes to psychological comfort, it doesn’t exist, I don’t have a problem with integrating, bring me any random person from the street, and In two minutes I will mingle with the person and we would be good together. By default, I’m sociable. But the psychological comfort is not there.” – Female, 35 year old, Sudanese, Amman

“Since our arrival, we realized that we needed to stick to one another to make it in this country. We must serve each other and form solidarity to support one another because no one will be able to help us.” – Male, 32-year-old, Sudanese, Amman

On aid / cash transfers

“We are afraid that the eye print will stop. What we need, and all refugees need, are jobs and employment opportunities, given that there is no aid.” – Male, 46-year-old, Syrian, Irbid

“We applied for assistance from aid agencies, but it’s tough to follow up. You need transportation to go and ask, and we can’t afford that.” – Female, 34-year-old, Syrian, Irbid (her brother has tumor and the expense of treatment is JOD 8500)

“There was this private donor. She wanted to give us donations, but she wanted us to shake her hands and take photos with her and I refused. Imagine this humiliation.” – Male, 55-year-old, Iraqi, Amman

On earning a living

“It’s not enough that you earn. Those living with you must also be able to earn.” – Male, 32-year-old, Somali, sharing housing with other single men

“I looked for work but no one accepted me. They told me what work we should give you?

They look at me and say, “how can we ask you to make coffee and clean?”. If I work, I would not let me children leave school.” – Male, 52 year old, Syrian, Irbid

“I swear I am afraid to apply for work. Any job. I am afraid. I am not worried about myself. I am worried about my wife and my child. If the police catch me, where will I go? I don’t want to go back Yemen, better to keep me in prison.” – Male, 33 year old, Yemeni, Amman

On managing expenses

“Before I gave birth it was slightly better, some days I wouldn’t cook, everyone would be on his own, but now there are extra expenses. I’d tell him I want milk for the baby, and he wouldn’t be able to provide. It made for psychological pressure. You have to provide now.” – Female, 21 year old, Syrian, Irbid

“Rent pressures us the most financially. Medical care we can suffer by taking pain killers. When we work for a day or two, we buy food that is cheap to get us going. But rent is difficult. It has been 2 months I have not paid the landlord and sometimes wait. But when he puts pressure I borrow from the guys. But even their situation is not any better.” – Male, 34-year-old, Sudanese, Amman

On savings

“With the corona lockdown, I realized how it is important to save even if we have little income. I had only 15 JOD worth savings.” – Female, 32-year-old, Amman

“I saved 1700 JDs with a Sudanese man, but he went away with the money. There were other Sudanese leaving money with him.” – Male, 34-year-old, Sudanese, Amman

On future plans

“I am not going back to Syria. I want to be resettled because I carry the burden of the kids. My son left school so that he can help me in our house expenses. That is the only reason why would I travel outside Jordan. Only for the education for children, but as for traditions and culture, stability and safety, it is here.” – Female, 34-year-old, Syrian, Irbid

“If you ask any refugee here about their dream, they would say that their dream is to get resettlement in a safe country where they can start a new life. Being in Jordan is like being stuck. Unless we move out we have no hope of achieving any of our dreams. In Jordan, our priority is to find work to support ourselves.” – Male, 32-year-old, Sudanese, Amman

Brief overview of our sample:

Financial phases among Nairobi’s refugees

By Julie Zollmann

In Kenya, our FIND research was just starting as COVID-19 arrived in the country, forcing us to move our interviews to the phone. While we couldn’t undertake a detailed mapping exercise with our 80 refugee participants in Nairobi, we were able to talk in some detail about refugees economic and financial lives. Before the economic disruption caused by COVID-19, most of our respondents had achieved some economic self-sufficiency and stability. Most said their economic lives were not improving or getting worse, they just sort of plateaued at livable levels of income. Those who tried to excel by running larger businesses or trying to get jobs, found they were often set back by their inability to get a work permit, properly license their business, or travel freely within the country to conduct their business. Many of our respondents lived in middle class apartments, costing $200-300 per month, using a strategy of living in groups to share the expenses, even as most earned fairly low incomes. Few were building significant assets or imagining making big investments to grow themselves in Kenya. To do so seemed full of risk. Instead, they were just getting by at this low level—but livable—level of equilibrium.

One respondent, a 24 year old man from Burundi told us, “I have skills, so I am able to do something, but I cannot because I am a refugee. When I have proper work documents, I will be a big person, but for now, I can say I’m average.”

Our second round of interviews in Nairobi begins in mid-August.

FIND research informs IRC report on livelihoods in Jordan and Lebanon

Ahead of the “Supporting the Future of Syria and the Region” Conference taking place at the end of June 2020, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) launched the report “A Decade In Search of Work: A review of policy commitments for Syrian refugees’ livelihoods in Jordan and Lebanon”. The World Economic Forum published an article summarizing its key points.

The briefing draws on new evidence and emerging research findings from the FIND research in Jordan on how refugees are managing their financial lives, and analyses the impact of policy decisions made in both Jordan and Lebanon on livelihood opportunities.

The report finds that while both Jordan and Lebanon have received substantial financial support from the international community to boost their economies and create job opportunities, the emphasis on supporting refugees has weakened over time. Investments and policies intended to lead to job creation have had a very limited effect. Refugees continue to face significant legal barriers to access jobs in both countries and their opportunities are constrained further by the COVID-19 crisis. Now more than ever there is a critical need for supporting livelihoods and enhancing prospects for durable solutions in both Jordan and Lebanon.

The international community should:

• Fund NGOs to address immediate basic needs and enhance long term economic recovery and refugee self-reliance in Jordan and Lebanon, including immediate and long term support for entrepreneurs.

• Reaffirm political commitment to both Compacts, continuing to link financial support to further national policy reforms.

• Define next steps for the renewal of Compact agreements, including an effective independent monitoring system based on quantitative and qualitative indicators.

National policy reforms in Jordan and Lebanon should:

• Expand access to decent work for refugees regardless of their nationality through lifting regulatory barriers.

• Expand opportunities for entrepreneurship and simplify business registration procedures and documentation requirements.

• Promote women’s economic empowerment by lifting barriers to work and entrepreneurship women face.

Financial Inclusion and Resilience for FDPs in the Time of COVID-19

The IRC and BMZ jointly published a CGAP blog to highlight the importance of access to financial services for refugees during times of crisis. The Roadmap to the Sustainable and Responsible Financial Inclusion of Forcibly Displaced Persons provides guidance on how to leverage digital financial services in humanitarian contexts to support FDPs. The COVID-19 crisis points to the vital role digital financial services can play for vulnerable populations by enabling transactions to occur while communities are in lockdown and supporting social distancing practices. There is a need to further facilitate dialogue and multi-stakeholder action to support the scaling of existing efforts and mobilization of new and innovative approaches, to enhance financial inclusion of refugees.