Why would affluent northern-European taxpayers want to pour money into an Italian economy that is a basket-case? Except it isn’t.

Behind the deadlock exhibited at the June European Council over the recovery fund lay continued scepticism among northern member states of the eurozone as to the entitlement of southern members to substantial financial support—most especially Italy. This disposition is however based on images of the Italian economy and fiscal policies which are at odds with the data.

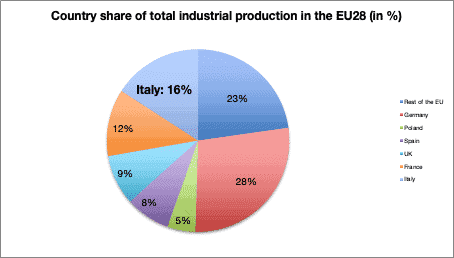

That is no accident: over the course of the financial and eurozone crises of recent times, economists, politicians and media have conveyed a distorted picture of Italy and its economy—clichés which European political leaders such as the Dutch and Austrian prime ministers still use today. They fail to recognise that Italy is the second largest producer of industrial goods in the EU, has been running export surpluses over recent years and has often adhered more strictly to the European Union’s fiscal rulebook than Germany, Austria or the Netherlands.

So here are seven myth-defying data about the Italian economy.

1. Italy is living below its means

‘Italy is living beyond its means!’ This omnipresent claim is readily supported by pointing to Italy’s public debt, which amounts to 135 per cent of its economic output. Yet this means only that the public sector is highly indebted—it says nothing about the Italian economy as a whole.

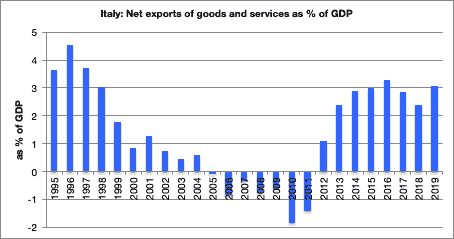

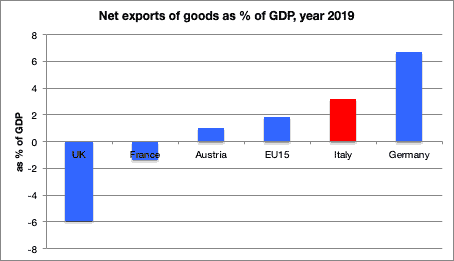

A country lives beyond its means if it imports significantly more goods and services than it exports over the long term. A country that exports as much as it imports is not however living beyond its means, as production and consumption are in line. Indeed, Italy has been recording export surpluses since 2012. Italy’s export surpluses are by no means only due to tourism, as the country exports more industrial goods than it imports. The Italian economy therefore consumes less than it produces—it lives below its means.

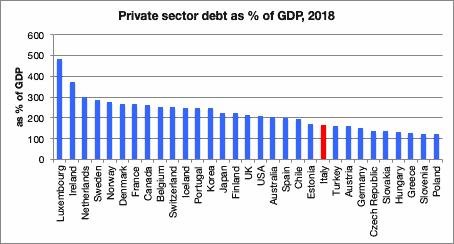

2. Private debt is not a problem in Italy

If the Italian economy as a whole has not been living beyond its means, the problem of debt must be confined to the public sector. This is indeed the case: Italy’s private-sector debt relative to gross domestic product is relatively low by the standards of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. This also illustrates that high debt-to-GDP ratios are not a problem across all sectors of the Italian economy.

3. Public debt is high because of errors made 40 years ago

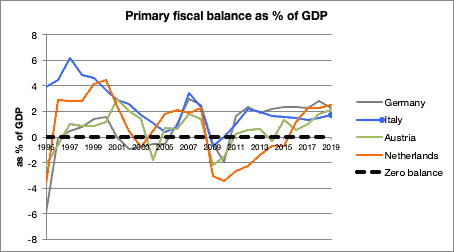

If the economy is not excessively indebted, why is the state so ailing? As disastrous as the performance of Italian domestic politicians from Silvio Berlusconi to Matteo Salvini has been, high public debt is primarily a legacy from the 1980s. Furthermore, the mistakes that were made 40 years ago took place in an international environment of increasing interest rates. Since then, the Italian state has been carrying a heavy interest-rate backpack. If we exclude the burden of interest rates, however, the Italian state has been consistently running budget surpluses since 1992 (with the exception of the crisis year 2009).

Even Germany, Austria and the Netherlands have recorded a comparable positive ‘primary’ budget surplus less frequently than Italy. The Italian state has not been as ‘profligate’ as is often claimed: it has consistently collected more in taxes than it has spent. But the interest burden—high due to legacy debt—has repeatedly pushed the overall budget balance of the Italian state into negative territory. By the way, Italy has so far also been a net contributor to the EU budget.

4. Italy’s economy has suffered since joining the euro

Italy’s government debt is also marked because its economic growth has been so weak over the last 20 years—being presented as a ratio to GDP, if the economy stagnates a state cannot grow itself out of a pool of debt, which already stood at 120 per cent of GDP in 1995. In this context, policy deficiencies, including vis-à-vis corruption and organised crime, should not be neglected. But Italy has never been a haven of political stability—the current government is the 66th(!) since the war—and mafia and corruption have long been embedded. Yet this did not hinder the Italian economy from developing quite dynamically at times.

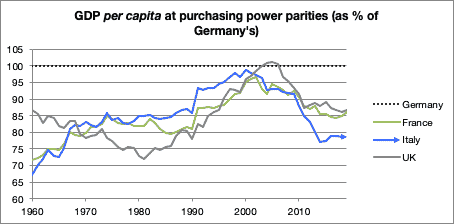

Italy overtook the United Kingdom in 1969 and France in 1979 in per capita purchasing power. In 2000, Italy’s average standard of living was virtually equal to that of Germany (98.6 per cent of its GDP per head). But after the introduction of the euro in 1999, the country fell behind the UK (in 2002) and France (in 2005) once more. By 2019, Italian per capita income was more than 20 per cent below that of Germany.

In the case of Italy, introduction of the euro and the stagnation in economic activity go hand in hand. One possible explanation is that the value of the euro reflects the average strength of all eurozone economies. The common currency is too cheap for Germany (which boosts German exports) and too expensive for Italy.

Whether Italy can ever regain economic momentum within the eurozone will to a large extent depend on the willingness of Germany and ‘frugal’ countries such as Austria and the Netherlands to reform the euro architecture—especially where European fiscal rules are concerned. In any case, countries such as Austria, the Netherlands or Germany, which have benefited greatly from the ‘cheap’ common currency, should do everything possible to keep Italy in the euro, in their own interest: any return to an ‘expensive’ currency, such as the D-Mark or the Schilling, would be a major burden for the industrial sectors in these strongly export-oriented countries.

5. Italy has carried out many market-liberal reforms

In 2015, the OECD assessed Italy’s ‘reform efforts’ as significantly stronger than those of Germany and France. The Dutch economist Servaas Storm takes a similar line. In an in-depth study he finds that Italy has adhered much more closely to the EU’s policy rulebook than Germany or France. We have already established that the Italian state has recorded greater fiscal-consolidation efforts than all other European partners—at a high price. Fiscal austerity has put pressure on domestic demand and, as a consequence, economic growth.

In the face of austerity, debt has remained high—what John Maynard Keynes called the ‘paradox of thrift’. As the German economist Achim Truger and his colleagues have shown, Italy’s austerity policy led to a dismantling of the healthcare system, which has proved fatal during the Covid-19 crisis. Moreover, drastic reductions in public investment have triggered a slowdown in Italy’s productivity growth.

But not only in the area of public finances has Italy been keen to comply with EU requirements. In 2014, Matteo Renzi’s government reduced workers’ protection against dismissal, extending labour-market deregulation which began in the 1990s. According to Storm, making the labour market more ‘flexible’—also in line with European requirements—led to a sharp increase in fixed-term contracts, pushed back the trade unions and contributed to a decline in real wages, compared with Germany and France.

‘Structural reforms’ from the market-liberal playbook not only reduced inflation in the 1990s. They may also have contributed to reducing unemployment, as the rate in Italy was lower than in Germany and France when the financial crisis hit in 2008. But cheap labour also diminished incentives for Italian companies to make labour-saving investments, key to the productivity improvements which are the basis for long-term growth and rising incomes. Both austerity and market-liberal reforms have inhibited Italy’s productivity growth and, on balance, may have brought more macroeconomic damage than benefits.

6. Italy is the second most important industrial country in the EU

It may sound surprising to northern-European ears but, despite weak productivity growth and problems with price competitiveness within the eurozone, Italy has important economic strengths. It is still the second most important EU location, behind Germany, for industrial production, mainly due to the economic structures in the northern regions. And it ranks third in exports of goods, just behind France, leading on mechanical engineering, vehicle construction and pharmaceutical products. This order is almost identical to Germany’s export structure, and the OECD classifies the industries concerned as ‘medium-high-tech’ to ‘high-tech’.

The historically grown industrial structure of (northern) Italy is only one example of the country’s great economic potential. If austerity and market-liberal reforms have not improved its outlook, a more promising way forward is to try an investment strategy, as the European Commission proposes, and to give Italy’s industry a boost by launching a modern European industrial strategy.

7. Italians are not richer than Germans or Austrians

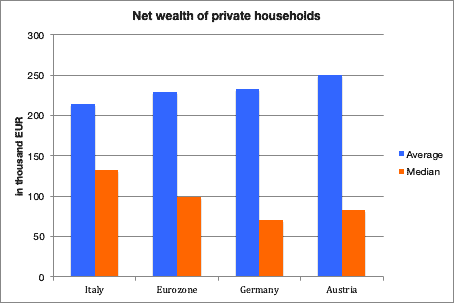

Finally, one often hears the argument that Italians are wealthier than, for instance, Germans or Austrians and should therefore pay for their investments themselves. The median Italian household, that located exactly between the richer upper half and the poorer lower half of the population, is indeed wealthier than the corresponding German or Austrian household. But the average Italian household—obtained by dividing the total net wealth by the total number of households—is clearly less wealthy than in Germany or Austria.

Although private wealth is lower in Italy, wealth distribution is more equal; in Germany and Austria, wealth is more heavily concentrated in richer households. One of the main reasons for this is that private-property ownership plays a greater role in Italy. This has a lot to do with the relative underdevelopment of the public safety net: social and co-operative housing, which provides many people in Germany and especially in Austria with affordable housing of a reasonable size, is rare. Social housing and co-operatives do not however count as private assets, even if people there live occasionally more comfortably than in Italian condominiums of poor standard. But it remains simply wrong to say that Italians are wealthier than Germans or Austrians.

Misrepresentations accepted

The images we have in mind when we think about the Italian economy are often not accurate. The German chancellor, Angela Merkel, and her then finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, gave free rein to these clichés a decade ago. At the time, the ingroup of German economists also largely accepted misrepresentations about southern Europe, to avoid considering a departure from the predominant mix of economic policies in the EU—a focus on fiscal consolidation and labour-market deregulation.

Several years later, the same economists and the same chancellor can see the results of these policies were counterproductive. The situation has become so acute that the issue of rebuilding the European economy after Covid-19 has the potential to tear the EU apart.

Now Germany—distancing itself from its ‘frugal four’ northern-European neighbours—wants to push for more investment in southern eurozone countries via the proposed recovery fund. But it will cost Merkel and German economists a lot of energy to convince the population of (northern) Europe—because of those false images of Italy and the south, tactically deployed over the course of so many years.

Philipp Heimberger is an economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) and at the Institute for Comprehensive Analysis of the Economy (Johannes Kepler University Linz). Nikolaus Kowall holds an endowed professorship in international macroeconomics at the University of Applied Sciences for Economics, Management and Finance, Vienna.