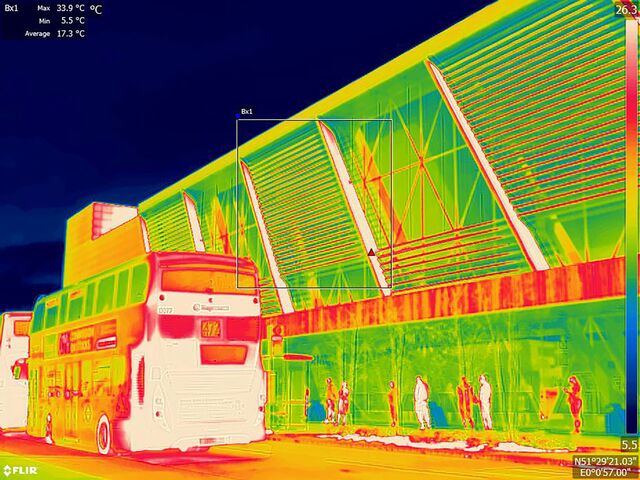

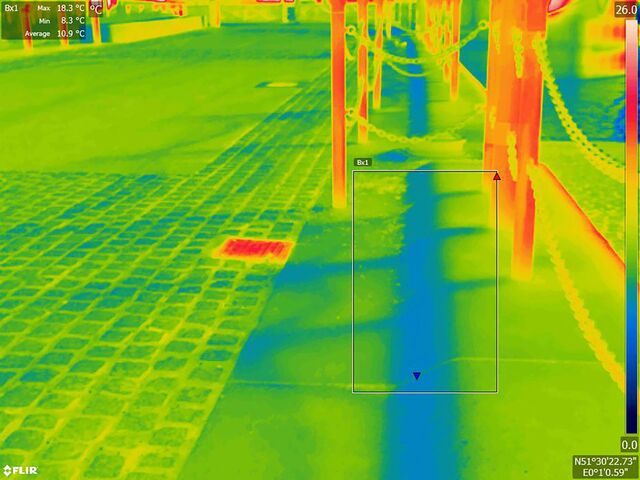

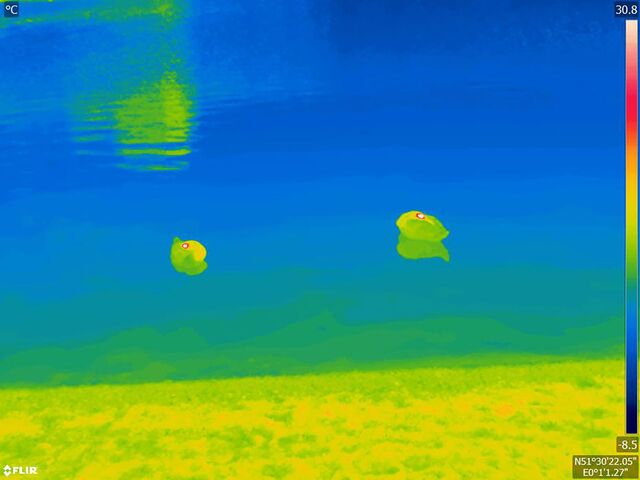

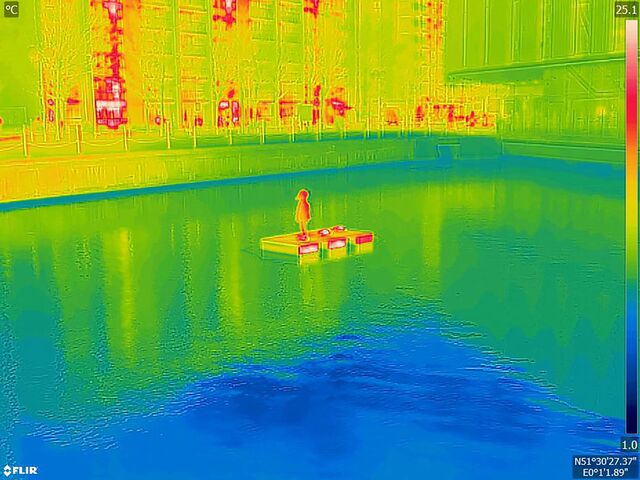

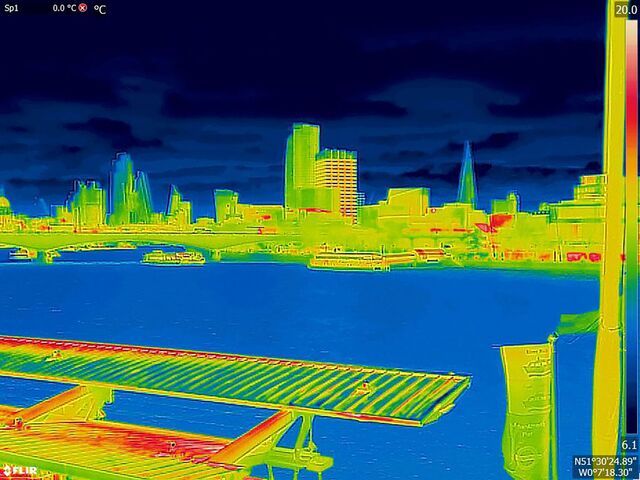

A Heat Camera Shows Where London Is Succeeding—and Failing—at Saving Power

An engineer takes us on a thermal tour of the city.

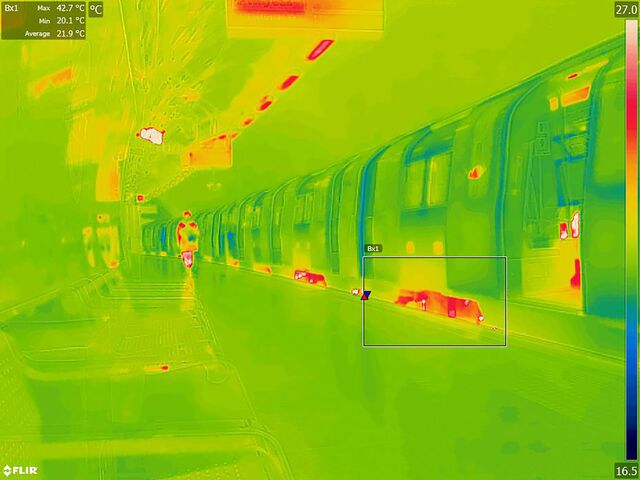

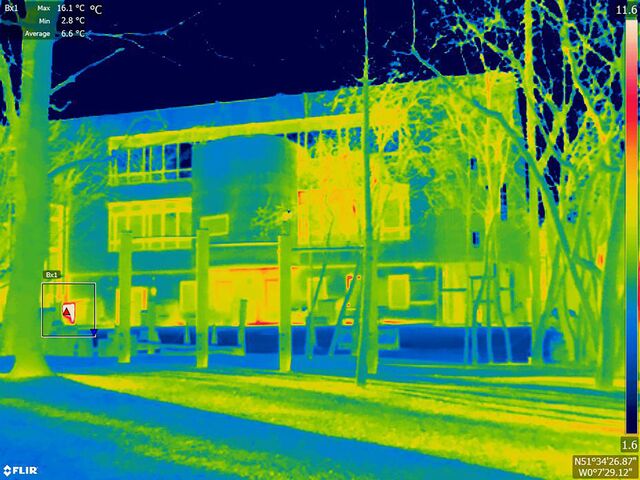

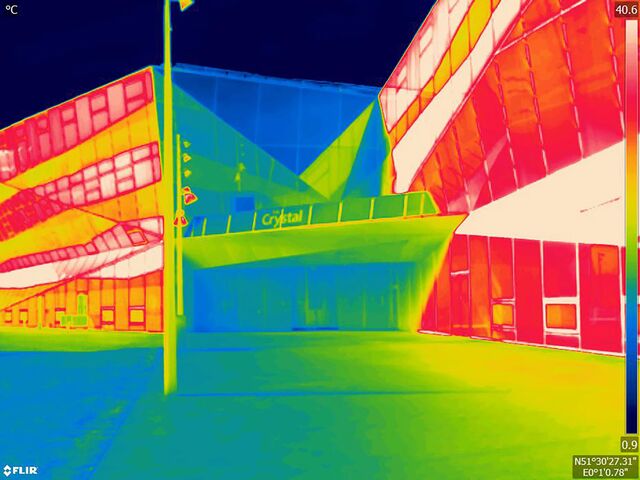

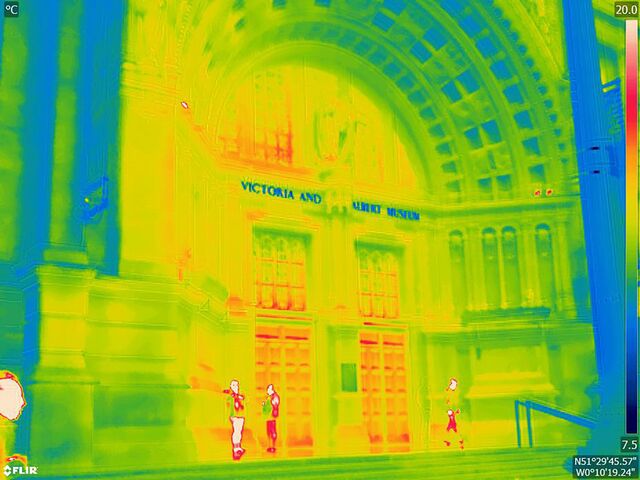

As anyone who’s braved crowded trains, buses, and highways to get out of the city on a sweltering summer Friday knows, the urban environment gets hot—a phenomenon known as the heat island effect. The big picture can be seen from space using satellite thermal imaging equipment, but to cool things down, we have to trace excess heat to its source. For the last 11 years, an electrical engineer in the U.K. named Paul Buckingham has been taking thermal images to persuade home- and business-owners to invest in efficiency. “I’ve become an investigator more than anything else,” he says. “What I’m finding is upsetting everyone in the construction industry.” In March he went to London on assignment for Bloomberg Green. His lens transforms the city, showing buildings, cars, and the Tube as collections of poor materials, bad insulation, and inefficient design.

Each thermal image has a scale showing the range of temperature captured, in degrees Celsius.

▼