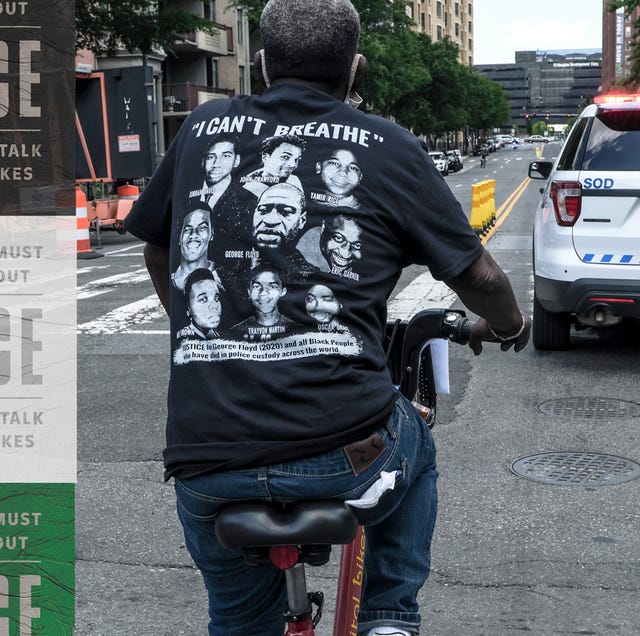

When George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others were killed by the police in 2020, forcing the nation into a racial reckoning, the cycling industry responded with promises to be part of the solution rather than part of the problem. Fuji announced it was suspending the sale of their bikes to police departments, while various other industry leaders committed themselves to increasing diversity in the sport of cycling.

Yet, looking at the actions of some cyclists at the top of the sport, along with their sponsors, I see how the system of privileges and advantages afforded to white people remains strongly rooted both inside and outside the sport of cycling.

It’s time for cycling to think beyond white fragility, white privilege, implicit bias, and microaggressions, and begin to think about its root cause. Cycling must reject interventions that continue to individualize anti-Black racism, and work to break down the structures that allow whiteness to retain power in the sport.

Anti-racist efforts within cycling must move beyond the trite euphemisms of inclusion, diversity, sensitivity, and allyship, and begin to seriously consider the dimensions of power at play. Yes, control of cycling resources are important, as are safe spaces to ride one’s bike, but the power of whiteness within cycling remains unsullied.

In late September, many in the sport turned a blind eye when it came to light that world-champion Chloe Dygert ‘liked’ several racist and transphobic tweets. One tweet said “white privilege doesn’t exist,” while another suggested that if football player Colin Kaepernick “realized that if he grew an afro and played the part of victim, he could scam the Black community out of millions.”

It took six weeks for her new professional team, CANYON//SRAM Racing, and Rapha, the clothing sponsor of CANYON//SRAM, to publicly condemn her actions. TWENTY20 Pro Cycling, the team she was with when she reacted to those racist tweets, and Red Bull, another sponsor, have yet to weigh in on the matter.

Dygert, who has since unliked the tweets, has faced no real consequences that we know of, so far. She hasn’t raced since crashing at the 2020 UCI Road World Championships in September of last year, but she has returned to training with Team USA ahead of the Tokyo Olympics.

Such public respect and civility toward Dygert, no doubt aspects of white privilege and power, allow her and her corporate sponsors a path to redemption, a means to restore or even reshape their image, build character and come out on top. And given redemption is nothing new to the sport of cycling, for one has to look no further than those accused and found guilty of doping.

As David Leonard states in Playing While White: Privilege and Power on and Off the Field, “To be white is to exist as an Angel even in the face of counter evidence.” This is obvious as Dygert made her own attempt at asking for forgiveness. In November of last year, she posted a photo of herself on Instagram, resplendent in her USA time trial suit and Red Bull aero helmet, head down as if exhausted from a long, hard effort—although this time, the head down appears to signal embarrassment, not exertion. In the caption, Dygert wrote the following:

“Cycling should be for everyone regardless of color, gender, sexuality or background. Like CANYON//SRAM Racing, I am committed to promoting diversity, inclusion and equality in cycling and our wider communities. I apologize to those who I offended or hurt by my conduct on social media. I am committed to keep learning and growing as an athlete and a person.”

To me, Dygert’s apology was out of context in that it lacks sincerity and does not refer to her transgression of liking racist and transphobic social media posts. CANYON//SRAM Racing released its own statement alongside Dygert’s, but neither apologies attend to the root of the problem—the white privilege and power that feeds anti-Black racism.

After those statements were released, Rapha emailed its own follow-up statement to its customers; it called out Dygert’s “very serious errors of judgment” and said that Dygert’s apology was not sufficient. On the surface, that statement appeased those who were disgusted with the world champion’s denial of white privilege.

However, if you frame Rapha’s statement within the context of the power and privilege of whiteness, you’ll see that it sets the tone for even greater redemption. Rapha, a global company that is conscious of its whiteness and unearned privilege, could be seen as trying to position itself as an ally. Yet, efforts at solidarity—working to be a good ally or destroying privilege—often become subtle quests to regain control over whiteness and thereby contain or incorporate the disruption to the brand. Their statement that Dygert’s actions were nothing more than a lapse in judgement opens up the channels for redemption.

What Dygert did was not simply a deviation in an otherwise magical career, but rather an expression of the violent normality of anti-Black racism in the world. While Rapha’s condemnation is no doubt more forceful than CANYON//SRAM, Red Bull, and Twenty20 Pro Cycling put together, framing it as exceptional only obscures the root of the problem.

Dygert isn’t the only cyclist who has been criticized for social media use. In early October, rookie Quinn Simmons was suspended from racing by his team, Trek-Segafredo, for sending tweets described by the team as “divisive, incendiary, and detrimental to the team.” Dutch cycling journalist José Been posted a now-deleted tweet that read, “My dear American friends, I hope this horrible presidency ends for you. And for us a (former?) allies, too. If you follow me and support Trump, you can go. There is zero excuse to follow or vote for the vile, horrible man.” Simmons, who is white, responded to that tweet by posting the word “bye” and a hand-waving emoji in a black skin tone, which many interpreted as being racist.

The team’s manager stated, “We remain committed to helping Quinn as much as we can.” Along with a two-month suspension, Simmons said the team underwent social media training in the offseason. He has since returned to racing.

As pro cyclist Kévin Reza recently pointed out, there needs to be zero tolerance for anti-Black racism in cycling. As powerful as Rapha’s apology might seem, anti-Black racism is still understood and framed to be an individual act. In other words, the whiteness of cycling, in part, is the ability to reduce anti-Black racism to a misunderstanding that can simply be overcome by introspection. And if we are honest, when it comes to managing diversity and moral missteps, the whiteness of cycling does not require dismantling the anti-Black world in which we all live.

Cyclists and the cycling industry must come to terms with the reality that cycling is a powerful narrator in the power of whiteness that feeds anti-Blackness. Anti-Black racism becomes all the more powerful because actions like those taken by Dygert and Quinn are simply seen as youthful, uneducated blunders.

If cycling and its stakeholders are to take anti-Black racism seriously, it must frame its understanding of the world beyond the individual. To proclaim that Black lives matter would also mean being attuned to the ways in which whiteness, as a position of power, continues to be normalized on and off the bike.

As scholar and recreational cyclist Tryon Woods makes plain in his recent book Blackhood Against the Police Power: Punishment and Disavowal in the "Post-Racial" Era, “the only ethical way of being white in the world is to tell the truth about anti-Blackness and to embark wholeheartedly on the affirmation of Blackness, as if life hangs in the balance—which it does.”

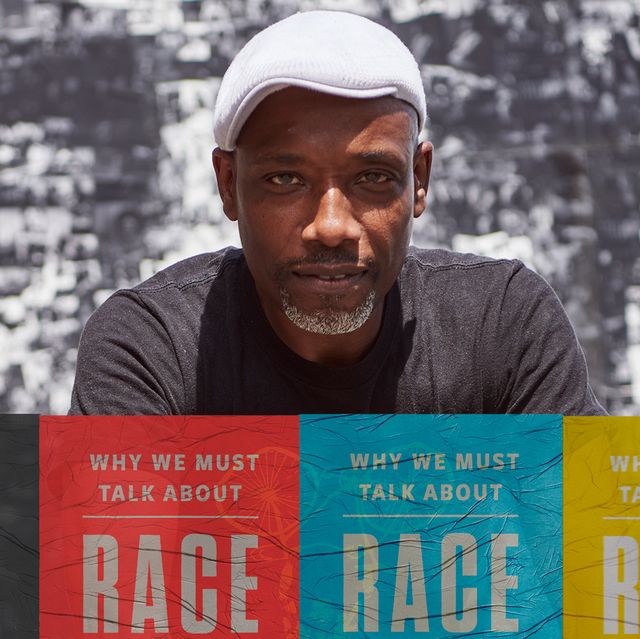

P. Khalil Saucier is Professor and Director of Africana Studies at Bucknell University. He is the author of the forthcoming book titled Black Frames: (Anti)Blackness and the Sport of Cycling.