This last year may have been one that most of us will remember as being dominated by feelings of uncertainty, social distancing and lockdowns, but there was no shortage of fascinating scientific discoveries. Here’s the proof…

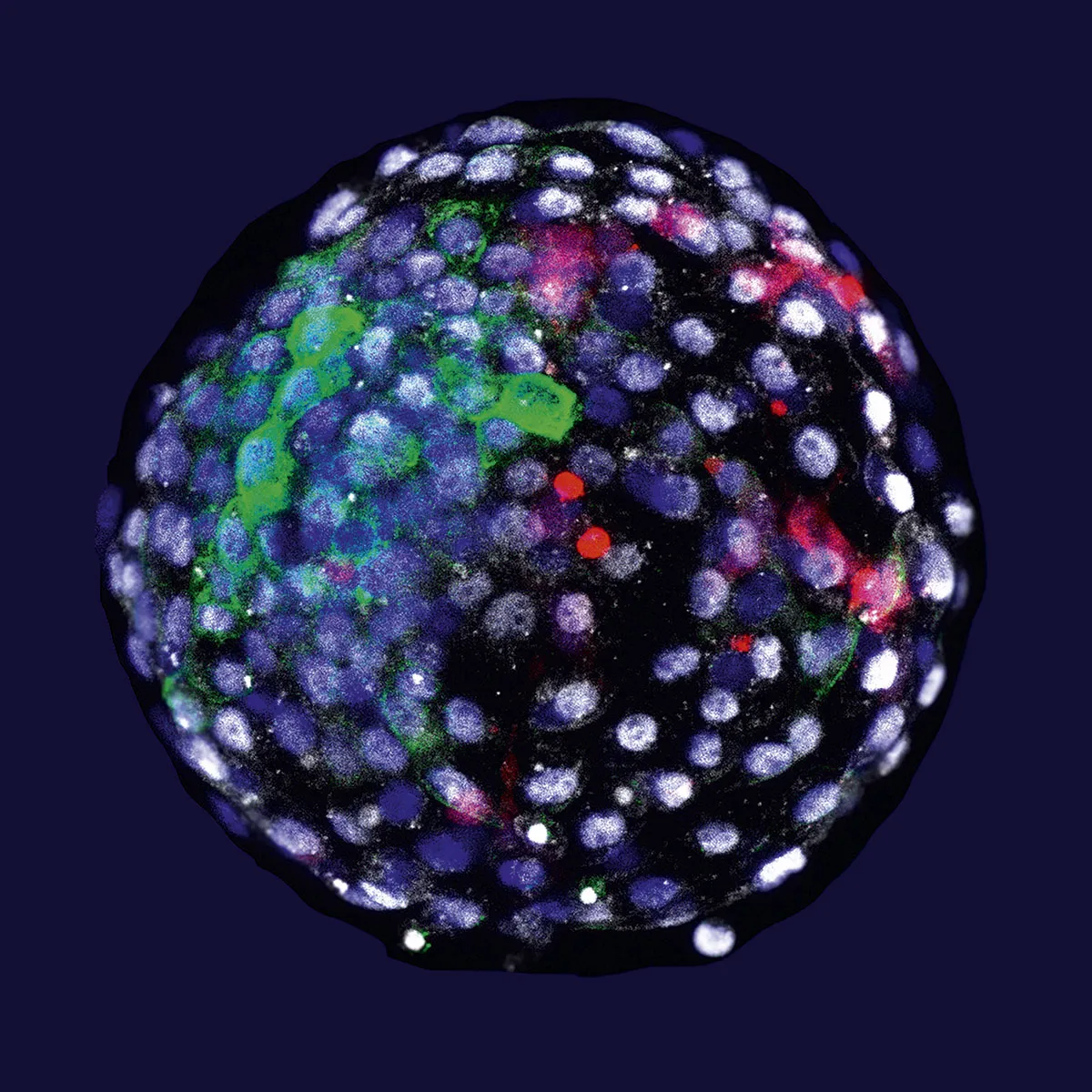

Human cells implanted into monkey embryos

A bold and controversial study, published in the journal Cell in April, reported how researchers at the Salk Institute in San Diego had inserted human stem cells into the embryos of monkeys. The embryos survived in the lab, outside of an animal, for up to 20 days – longer than in any similar experiment. The researchers also noticed communication pathways form, which may explain how human cells could better integrate with non-human cells in future experiments.

Work on this kind of hybrid organism, known as a chimera, is conducted for two main reasons. First, it could allow researchers to create ‘model’ human cells to study disease and new drugs, without breaching the ethical codes that prevent the same work being carried out on actual humans. Second, it could enable the growth of new organs for human transplant.

Researchers have tried the same thing with other animals, such as sheep and pigs, in the past, but the chimeras didn’t survive for long. Pairing the human cells with a non-human primate is both the reason it worked better (because we’re closer in evolutionary terms) and the reason the work is controversial.

“The closer your model gets to being human, well, the closer your model gets to being human,” said Prof Henry Greely, director for the Center of Law and Biosciences at Stanford University. He co-authored a response to the Salk study, laying out some of the ethical questions this kind of work raises.

“Xenotransplantation is one of the long-term goals here: to make human organs in another animal and use them for human transplants,” he said.

“That’s a big deal if you can pull it off. But on a journey of 500 miles, this is a step of one metre. The ethics side is exciting, but depends largely on what happens next.”

Greely believes that as long as you’re growing the embryos in a dish, it’s not a big deal, as far as ethics are concerned. But what if the work advances, and goes from being an embryo in a dish, to one growing in a womb, with a significant number of human cells, which continue to survive?

“That becomes a really interesting question. One is animal welfare: do you let these things be born? What are they? I don’t think they’re humans, but it’s hard to know.

"Let’s say one of them is born and has an enlarged skull and a big brain that looks pretty human. What do we do with that? I think a good starting point for society to come to is [to say]: ‘Yeah, we may want to play around with these, but we don’t want to implant them.’”

While this kind of biotechnology remains some way off, the field is developing rapidly and Greely says that existing bioethical and legal frameworks are struggling to keep pace. He’d like to see more ‘horizon-scanning’ groups, whose job it is to look at the direction of travel for a particular kind of research and ensure society is having the required ethical conversations in good time.

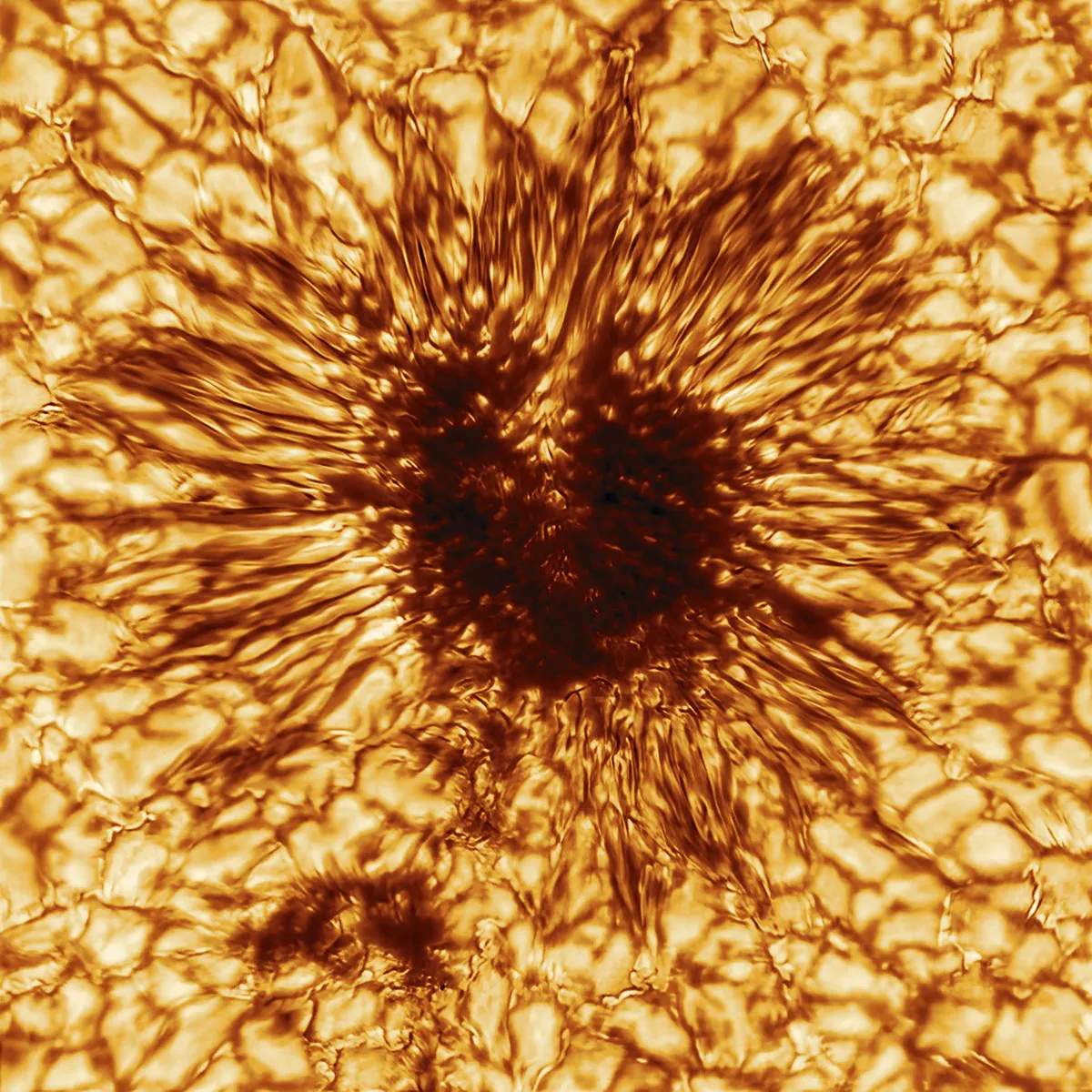

Solar telescope captures most detailed view of a sunspot ever

Staring at the Sun is never a good idea, but we’ll excuse astronomers using the Daniel K Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii. This year they released the most detailed view of a sunspot ever captured.

The innovative telescope captures higher resolution solar imagery than ever before and uses a technology called adaptive optics to correct some of the distortions, caused by Earth’s atmosphere, that would normally fudge the image. The result: a frightening-but-fascinating look at our star’s behaviour, which could eventually help us predict GPS-bothering solar flares. Looks a bit like the Eye of Sauron, no?

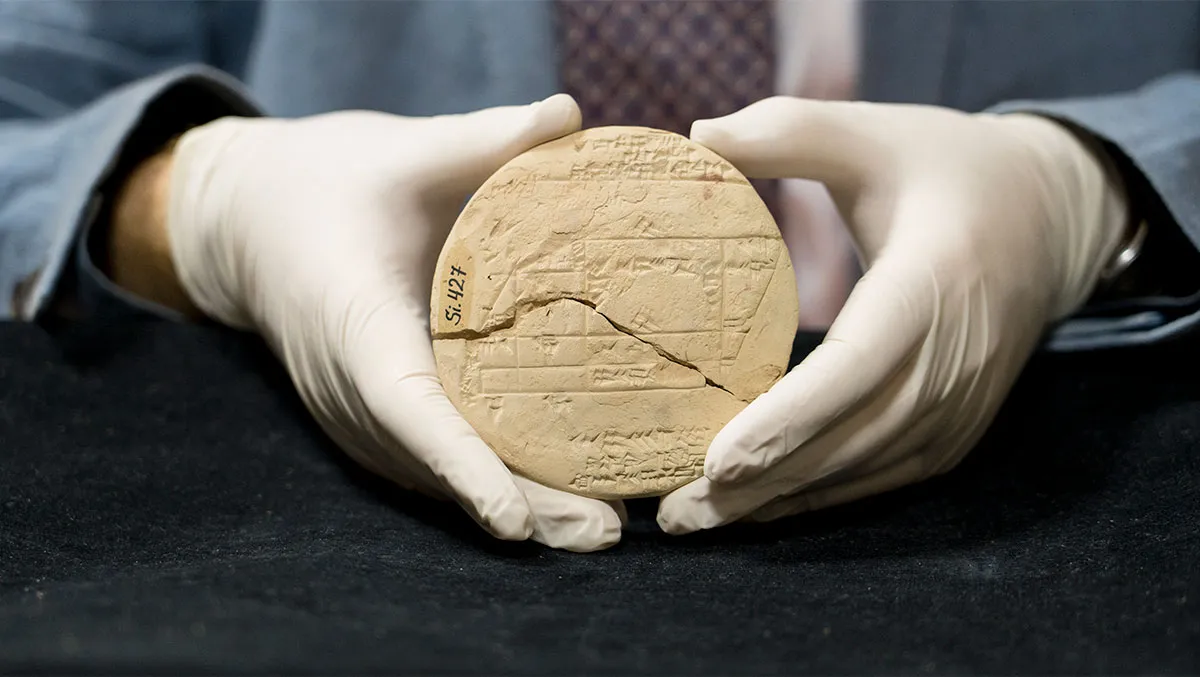

Pythagoras' Theorem was in use 1,000 years before his birth

Like 1066 and oxbow lakes, Pythagoras’ Theorem was one of the things we all picked up at school. But it seems that Pythagoras wasn’t the first person to suss it out.

(A quick refresh: the sides of a right-angled triangle follow the equation a2 + b2 = c2. So if you add the squared lengths of the sides that form the right angle, you’ll get the squared length of the hypotenuse.)

August saw Australian mathematician Dr Daniel Mansfield publish his analysis of a 3,700-year-old tablet found in Iraq. It showed that Babylonians were using the same rule to mark and divide up land over 1,000 years before Pythagoras was born.

Is it high time for psychedelic therapies?

After years of mainstream resistance, the world is, in more ways than one, beginning to change its mind on psychedelic drugs. The therapeutic benefits of magic mushrooms, LSD and other hallucinogens are increasingly supported by hard-to-ignore evidence, as the substances become the subject of a major research focus. In 2021, we may even have reached a tipping point of acceptability, not least because of the stark results from one study at the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London.

It found that psilocybin, a substance derived from magic mushrooms, was at least as effective in treating depression as escitalopram. All the patients also received psychological support during the trial. This was a randomised, controlled, double-blind study, and the head-to-head design suggests that psilocybin offers better outcomes for patients than escitalopram, which is one of the most commonly prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

“On almost all measures, psilocybin worked significantly better and faster than escitalopram and was at least as well tolerated,” said Prof David Nutt, one of the study’s authors. The measures include self-reported symptoms, chance of remission and adverse side effects.

Psilocybin remains a class A drug in the UK and possession is punishable by up to seven years in prison. Elsewhere, however, its legal status is being reassessed. “In the US, many places are removing the illegal status of magic mushrooms in part to accelerate research and treatment,” Nutt says. “The UK is lagging behind despite our being leaders in the field.”

Perhaps spurred on by the success of medical cannabis (economic as well as therapeutic), there’s a growing sense of normalisation about the substances and their therapeutic potential. Multiple studies on a wide spectrum of conditions are either planned or underway all over the world.

“We have started our trial of psilocybin in anorexia nervosa and will start one on obsessive compulsive disorder and pain in the new year,” Nutt said.

He and his colleagues are also researching other psychedelics, such as LSD and DMT, while another strand of investigation focuses on the therapeutic practicalities of using these drugs.

Earlier this year, researchers at University of California, Davis, reported work on a psychedelic compound that may not have hallucinogenic side effects. This could be important as those kinds of side effects require that patients receive a lot of hands-on psychological support before and after treatment.

Meanwhile, a team at the University of Copenhagen found that psilocybin enhances our emotional response to music – something they say should be considered if the drug is approved for clinical use.

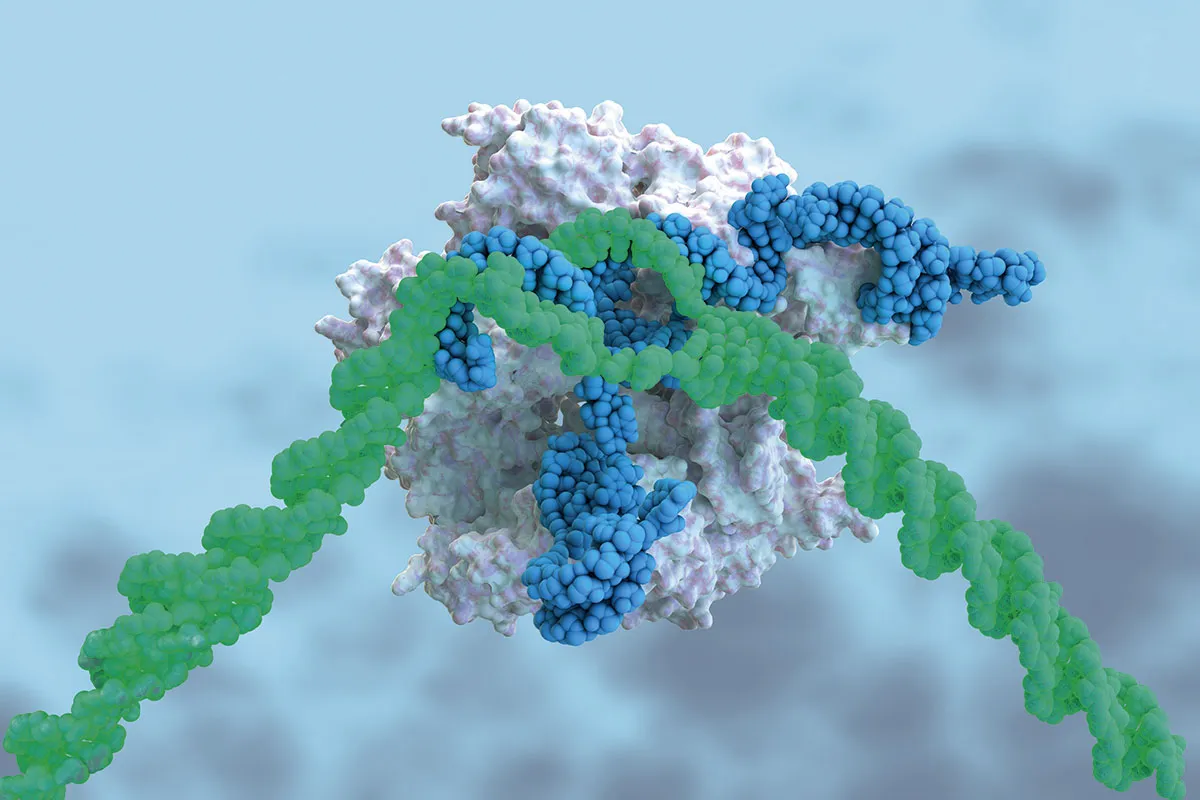

CRISPR gene editing injected directly into bloodstream

Gene editing is a branch of science developing at paradigm-shifting speeds and this year, the milestones in human health kept coming. In June, researchers announced extraordinary results from an extraordinary new technique, where the CRISPR Cas-9 gene editor was – for the first time – injected directly into the bloodstream of a patient with a rare inherited disease.

Normally, CRISPR works by extracting cells from a patient, editing them in a lab and returning them to the body. It’s costly, time-consuming and hard on patients who sometimes undergo chemotherapy as part of the process.

The CRISPR technique was relatively quick, and successful too: the treatment saw a huge decline in destructive proteins that build up in the body’s organs and tissues in the previously untreatable condition transthyretin amyloidosis.

Cats love to sit in imaginary boxes

If I fits, I sits. Cat lovers everywhere know how much felines enjoy sitting in a box. The behaviour, observed in big cats as well as domestic moggies, is believed to make them feel safe and concealed – handy, because they evolved as ambush hunters.

Now a citizen science project led by researchers at Columbia University in New York has found just how deep-rooted the behaviour is. The project found that cats will even sit in imaginary boxes. Cat owners created square shapes on the floors in their homes, using stickers or tape, and watched as their pets plonked themselves in the middle of them.

Humanoid robot learned to lip-sync

Watch out Cyberdyne Systems! This year roboticists at Edinburgh Napier University developed a humanoid robot that can lip-sync with speech. The robot, which one of the designers modelled on his dad, borrows technology first developed for 3D animated characters.

Using an algorithm that recognises patterns in speech, the robot interprets that data as jaw and lip movements, accurately mimicking the way a mouth moves to produce speech. Despite the warnings of James Cameron’s back catalogue, researchers say this kind of robot will help people interact with technology in new ways.

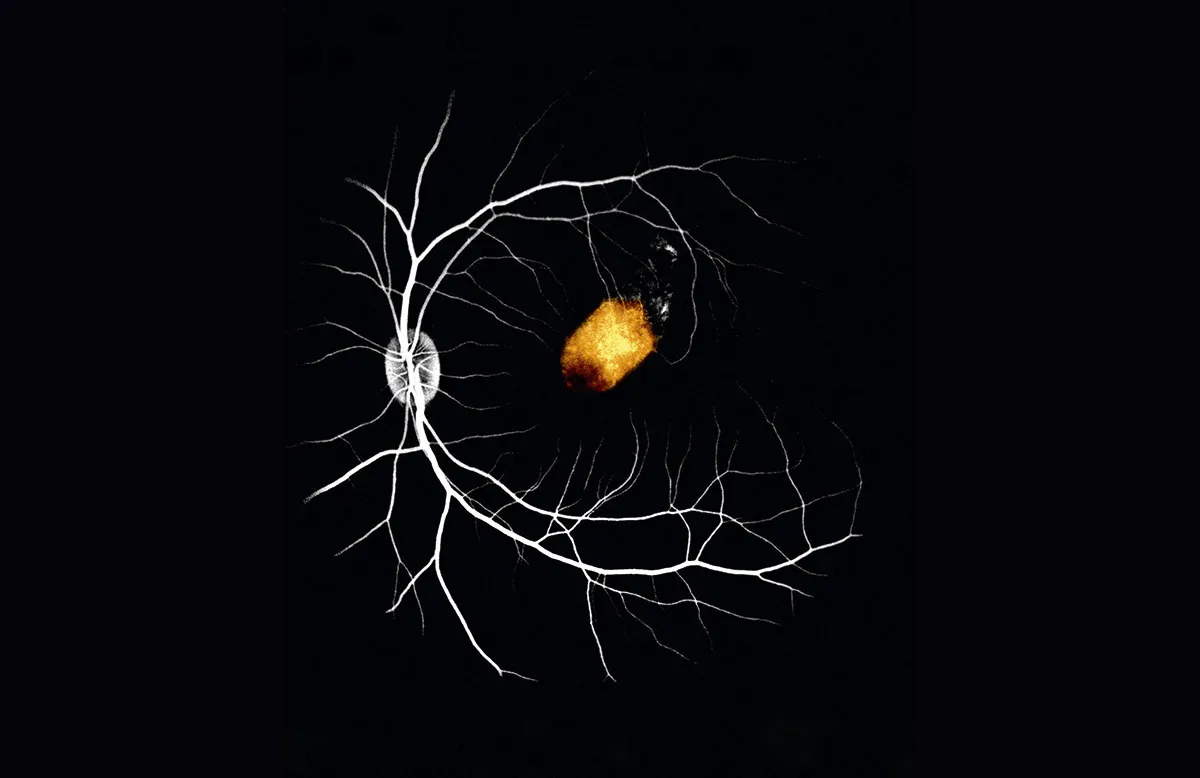

A blindness treatment is in sight

Hope continues to grow that we will soon be able to treat and reverse blindness, with a number of promising avenues of research showing progress. This year, researchers successfully transplanted human retinal cells into the eyes of monkeys. The researchers that carried out the procedure found no signs of unwanted side effects, such as light sensitivity or dangerous immune responses.

Grown from human stem cells donated to science, the cells began to take over control of some functions of the monkeys’ eyes. Human trials may not be far away, but researchers at Icahn School of Medicine in New York say that first the technique needs to be tested on monkeys with impaired vision.

Artificial titanium hearts could save lives

Researchers have been trying to build an artificial heart for more than 50 years. Now, an Australian team is planning human trials for a design that could have huge implications for our health.

BiVACOR is revolutionary because it doesn’t attempt to work exactly like a real heart – it tries to one-up evolution instead with an efficient and sustainable way to pump blood around the body. It utilises spinning disc technology, which sees a circular pump suspended between magnets in an artificial heart made of titanium.

So far, the technology has only been tested in animals and temporarily in heart transplant patients, although a full human trial is on the horizon. If it works, it could be massive – a quarter of all UK deaths result from heart disease.

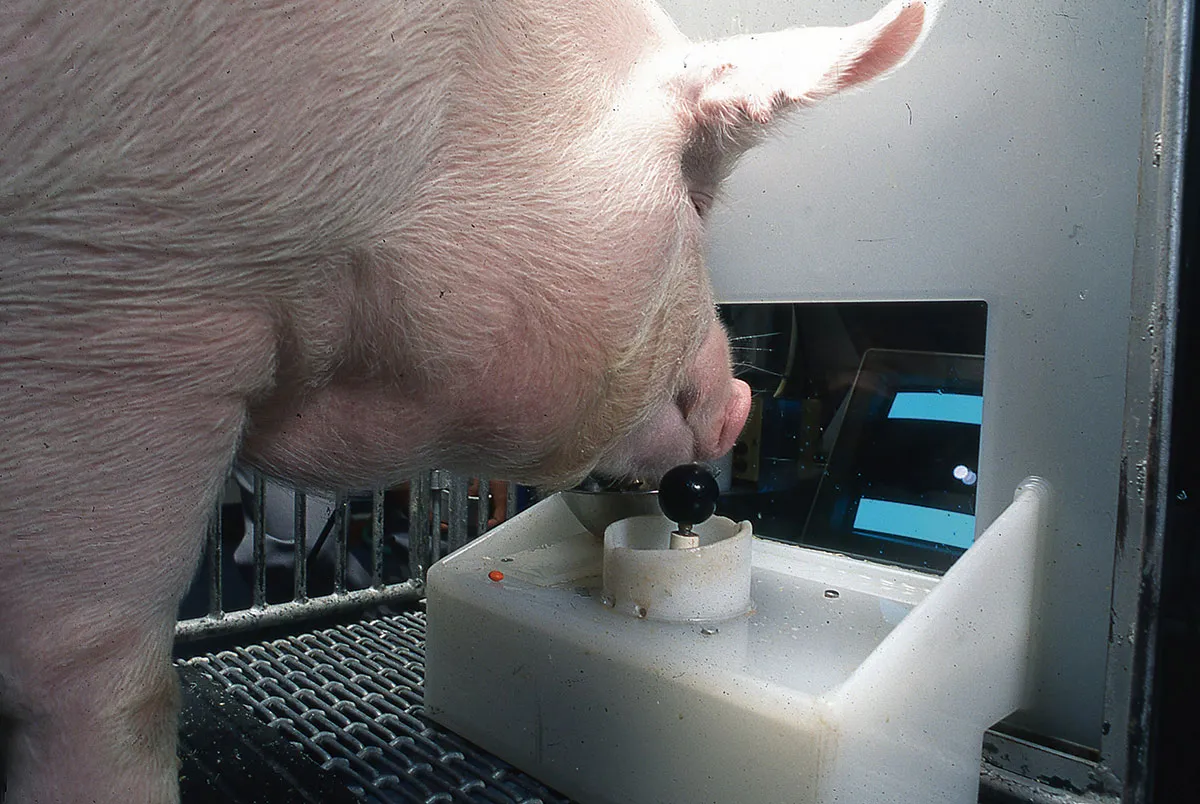

Pigs taught to play video games

It sounds like total trotters, but pigs are smart enough to play video games. In a study at Purdue University, four pigs moved a joystick with their snouts to direct a cursor to on-screen targets.

Researchers noted that their performances were well above those that could be explained by chance, and that the pigs responded to food rewards and verbal encouragement. It’s the latest work to hint at the breadth of porcine intelligence, with past research highlighting their learning, memory and problem-solving abilities. Don’t you hate it when another player hogs the joystick, though?

As the research base grows, it might not be a case of if, but when we find ET

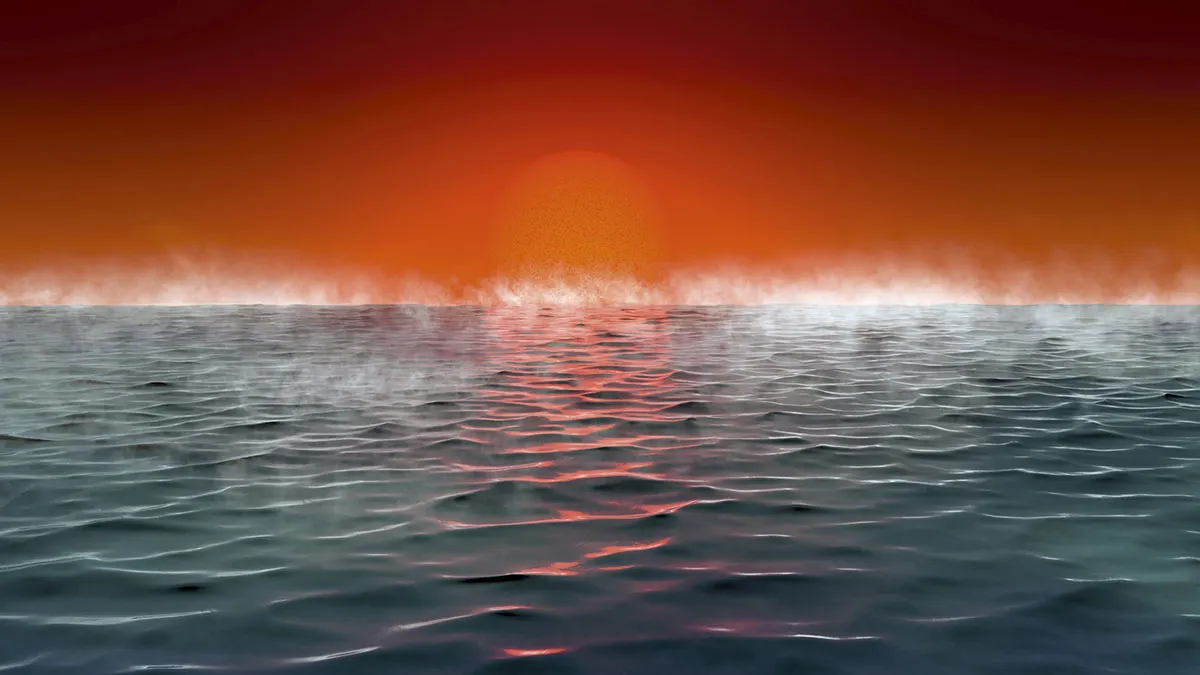

Somewhere out in the depths of the cosmos, life could be thriving on a strange kind of planet. Around 2.6 times the size of Earth, this alien world would be hot and covered in ocean, with an atmosphere that’s rich with hydrogen. Humans couldn’t survive there, but maybe we could detect the creatures that do. It’s even possible we could make that detection – and confirm that we’re not alone in the Universe – in the next two or three years.

This radical idea comes from researchers at the University of Cambridge, who published a paper in August speculating on the existence of such a world. Researchers have dubbed the category a world like this would belong to as Hycean planets.

If the existence of Hycean planets is confirmed, it could turbocharge the search for extraterrestrial life because detecting biosignatures from such worlds is potentially a lot easier than doing the same for Earth-like planets. Plus, a lot of already known exoplanets could fall into this class.

“The fundamental advancement here is that this idea will expand and accelerate the search for life elsewhere,” said study author Dr Nikku Madhusudhan. “In a very practical sense, it literally increases our chances.”

Traditionally, astronomers have scanned the skies for hints of oxygen, methane and other biomarkers produced in large quantities by microorganisms here on Earth.

“On Hycean worlds, we’ll be looking for molecules such as methyl chloride and dimethyl sulphide,” said Madhusudhan. These are also produced by life, but in much smaller quantities – something that’s not a problem when it occurs on Hycean worlds.

“The observability of these [planets’] atmospheres would be so good that even if these molecules are present at one part per million, they’ll still be observable,” he said.

Madhusudhan hopes to take advantage of the James Webb Space Telescope, the largest space telescope ever built. He believes that all it would take is a few hours trained on a Hycean planet for the telescope to pick up biosignatures using transit spectroscopy (a technique in which researchers measure the changes in starlight as it filters through the atmosphere of a planet that’s passing in front of it).

As significant as such a discovery would be, it would also beg further questions. “One fundamental question would be: is life possible in such environments? And how would life originate on this planet? You need to do a lot more follow-up observations to robustly establish whether [what you’re seeing] is indeed a signature of life,” said Madhusudhan.

“I may be risking making a big statement here, but this could be our entry point to extraterrestrial biology. But if you’re quoting me on that, please make it clear I’m saying it with some caution!”

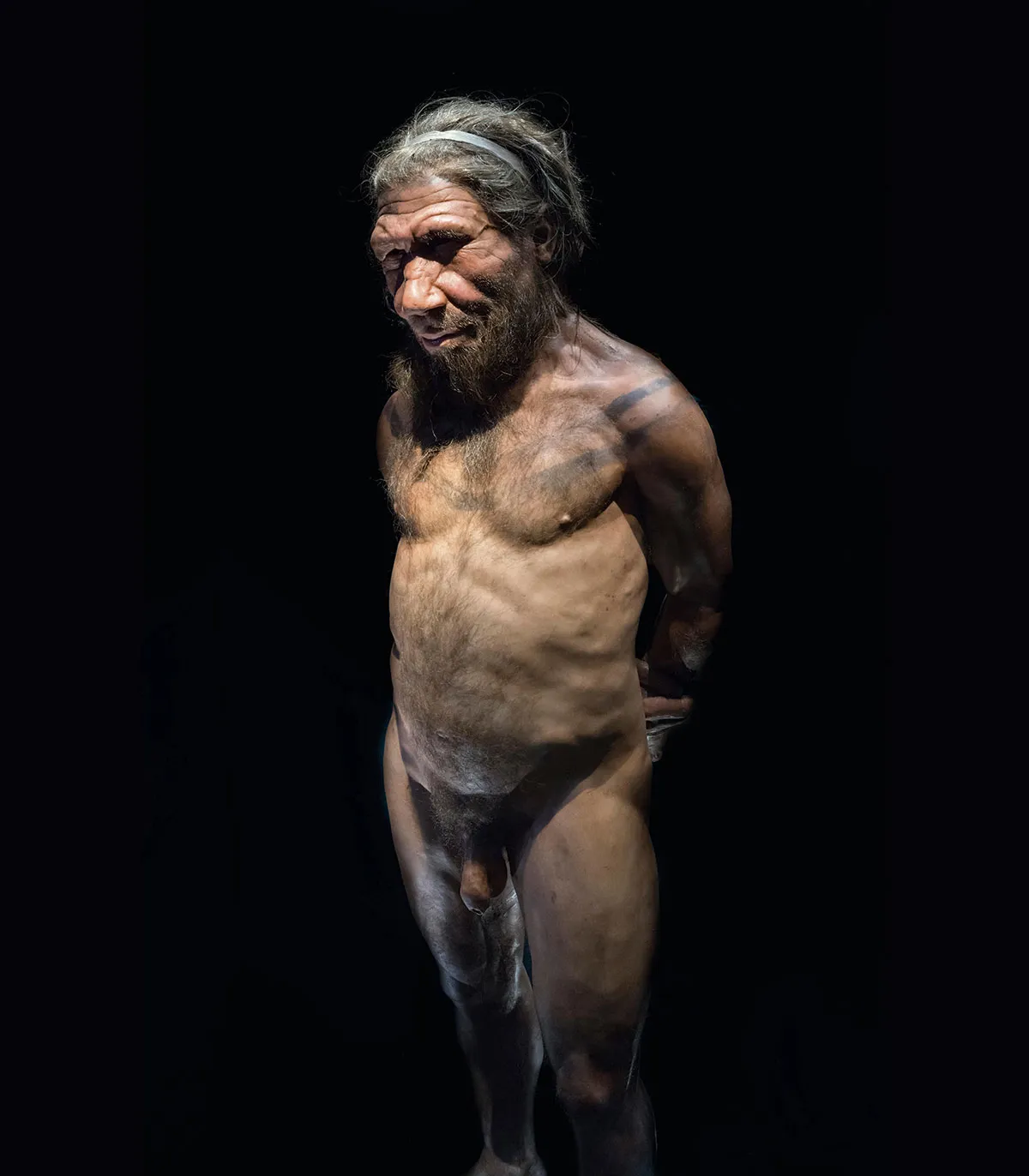

Could Neanderthals talk like us?

Big talk from palaeontologists this year, who claimed that Neanderthals had the capacity to hear – and possibly speak – just like us high-minded Homo sapiens.

Once dismissed as uncultured knuckle-dragging cave-dwellers, perspective on our evolutionary cousins has been shifting in recent years. They may have worn ornamental dress, for example. We certainly share DNA with them, and now researchers believe there’s a good chance they were capable of sophisticated verbal communication.

The conclusion comes from researchers in Madrid, who created 3D models of the ear structures of Neanderthals, allowing them to model the frequencies at which they could hear. Neanderthal hearing was attuned to frequencies around 4-5kHz, which happens to match the majority of human speech sounds. Researchers believe if they could hear it, there’s a good chance they could speak it.

What have we found at Mars this year?

2021 has been a busy year for the Red Planet. Three missions arrived in February, having set out seven months before to take advantage of the alignment of Earth and Mars’s orbit, an event that only happens once every 26 months.

The first mission to arrive on 9 February was the United Arab Emirates’ Hope orbiter, the nation’s first planetary mission. The spacecraft’s goal is to study the past and present climate of Mars from orbit. Unlike previous missions from other space agencies, which would only look at specific locations at the same time, Hope will look at changes throughout the day. Over time it will monitor Mars’s daily, monthly and yearly changes to build up a comprehensive image of what the weather is like on the Red Planet.

The next arrival – Tianwen-1, belonging to the Chinese National Space Agency (CNSA) – reached Mars a day later, on 10 February. The spacecraft spent its first few months at Mars surveying the surface from orbit, reconnoitring for the next stage of the mission: setting down the Zhurong rover. The CNSA eventually selected a site in the large Utopia Planitia and successfully touched down on 22 May.

The main goal of the mission was a test of China’s ability to operate on the surface of Mars, paving the way for future missions, however, both orbiter and rover are equipped with cameras, radar and spectrometers that will continue to survey the planet’s surface and atmosphere.

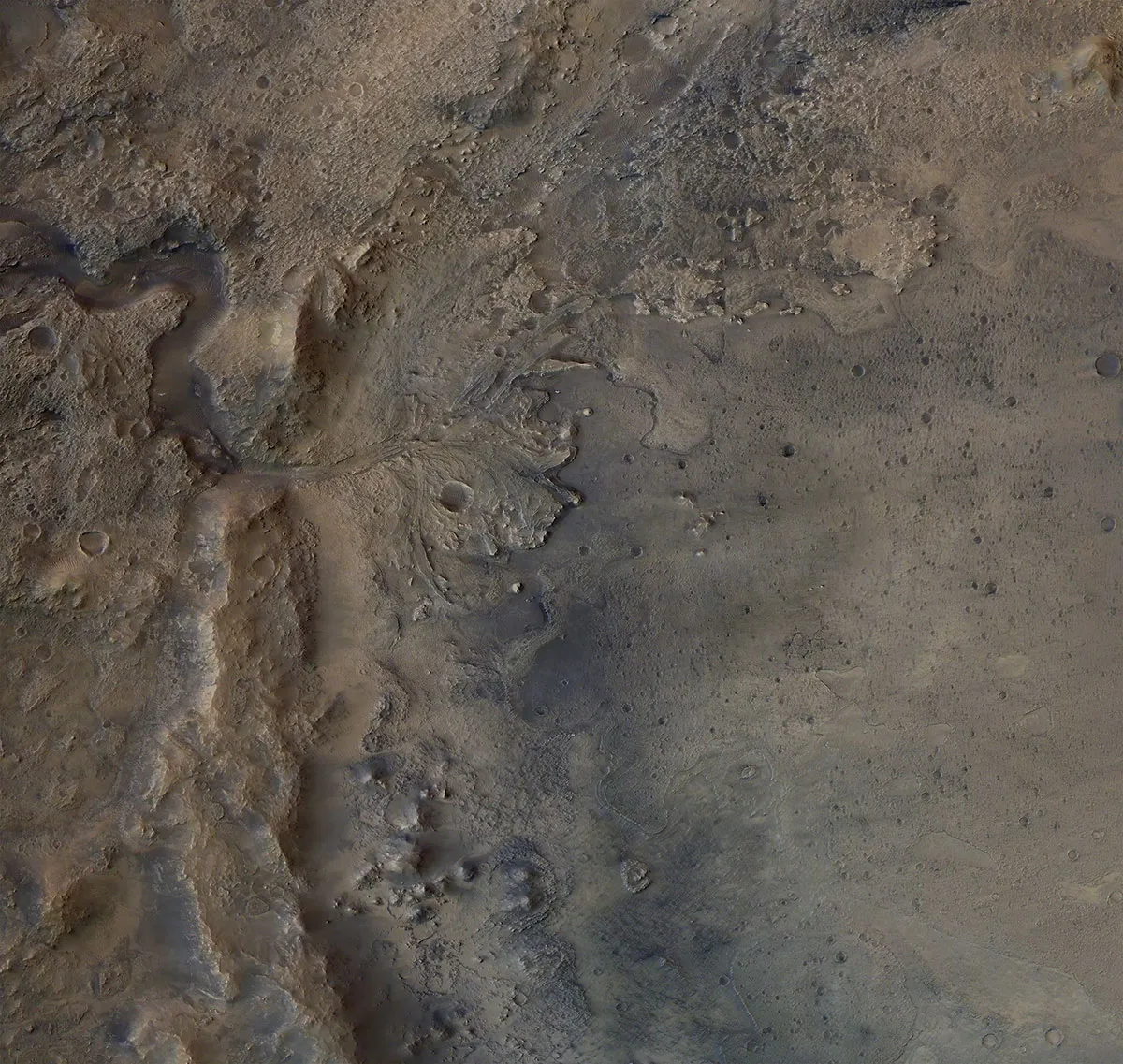

But, back on 18 February – before the Tianwen-1 mission had located a landing site for the Zhurong rover – the last, and largest, of the three missions arrived at Mars, in the form of NASA’s Perseverance lander. It touched down in the Jezero Crater, near what appears to be the site of a past river delta, making it a great place to study the history of water on the Red Planet and its potential past habitability.

Perseverance is closely based on the design of its predecessor, Curiosity, but has one major addition – a suite of instruments dedicated to drilling and storing rock samples from the Martian surface. But although Perseverance is a highly equipped robo-geologist, there’s only so much you can pack onto a rover and send to Mars.

To truly understand the planet (particularly if we want to find evidence of any past life) scientists need to be able to study a Martian sample in the best labs here on Earth. Perseverance represents the first step in that process. It will spend the next few years travelling across Jezero Crater, collecting up to 43 rock samples that it will then leave in caches for a future Sample Return mission (currently being planned by NASA, in collaboration with the European and Japanese space agencies) to collect and return to Earth.

Perseverance attempted to collect its first sample on 5 August, only to discover the next day that the sample vessel was empty, as the rock appears to have crumbled as Perseverance pulled it out of the ground. The rover moved to a more solid-looking rock, nicknamed Rochette, and successfully stored its first sample on 7 September.

At the time of writing the rover had travelled over 2.6km – quite a fast pace for a Martian rover. Its progress has been aided in large part by a spacecraft that hitched a ride to Mars with Perseverance: the Ingenuity Helicopter. The small drone-like rotocraft is a technology demonstration mission, intended to see if it’s possible to fly through the thin Martian atmosphere, the answer to which is a comprehensive ‘yes’. Since its first 39-second test flight on 19 April, Ingenuity has flown over a dozen times, travelling more than 2km.

More elaborate missions using the same technology are being planned, but as Ingenuity is only equipped with a camera, it’s being used to scout ahead of Perseverance, highlighting any potential hazards or objects of interest.

So what have we learned at Mars this year? The UAE learned how to orbit, China learned how to land, and NASA learned how to fly.

- This article first appeared inissue 371ofBBC Science Focus Magazine–find out how to subscribe here