Books Reviewed

On the evening of February 12, 1974, a notorious criminal—considered to be one of the most dangerous men in the world—was taken from an infamous prison, flown out of his country, and unceremoniously dumped in Cologne, Germany. His jailers would have preferred to kill him, but, frightened of the consequences, they instead sentenced him to permanent exile. Incredibly, this man—who had terrified the rulers of a vast empire—was not the leader of a rival country, a terrorist group, or a political party. His only weapons were a strong-willed spouse, loyal friends, an exceptional memory, and a literary talent matched by few of his contemporaries.

The ex-convict was Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. He had spent eight years in the Soviet Gulag after writing an offhand jibe about Stalin in a letter to a friend. There, as one of millions of innocent people sent to the camps, he witnessed firsthand the ineptitude, brutality, and injustice of the Communist system. He vowed retribution. Solzhenitsyn had committed to memory the atrocities of the Soviets, and he set about chronicling them after his release.

He slipped through a crack in the Soviet monolith when Nikita Khrushchev allowed the novella One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, set in a Soviet labor camp, to be published in 1962 as a way of discrediting Stalin’s followers. The book became a worldwide sensation and so raised Solzhenitsyn’s international profile that he was able to publish The First Circle and Cancer Ward in the West in 1968 without serious reprisals. In 1970 he won the Nobel Prize for literature.

A year later, when the ruling Politburo got wind that he was working on a historical account to be called The Gulag Archipelago, the KGB was instructed to assassinate Solzhenitsyn with ricin poison. He survived, but agents seized a manuscript of the Gulag. Solzhenitsyn’s friends spirited versions of the book to the West where it was translated into English, French, and German. As it happened, the fears of the Politburo were justified: The Gulag Archipelago discredited the worldwide Communist movement, most significantly in France, where it decimated the once-powerful French Communist Party.

* * *

Between Two Millstones: Sketches of Exile, 1974–1978 begins on the evening when Solzhenitsyn was banished from the Soviet Union. The Russian title can be translated as “the little grain between two millstones” and better captures the true tone of this autobiographical sketch of his first years in the West. The book is expertly translated by Peter Constantine with the assistance of the Solzhenitsyn family and under auspices of the Center for Ethics and Culture Solzhenitsyn Series at the University of Notre Dame.

It tells the story of an artist who had learned to lay low and keep out of sight—to become invisible. The written word was his way of communicating with the world. Suddenly and unexpectedly, he was thrust into the spotlight. In the West, reporters and photographers hounded his every step. Few, if any, had read a word he had written. To them, he was merely another celebrity, like a rock star. Their superficiality got under his skin. His mission was to destroy an evil empire; their goal was to get a cute anecdote or an embarrassing picture. Paparazzi pursued him relentlessly, so much so, that in a free society, he never felt free. Exasperated by a group of photographers following him on a walk, he shouted, “You are worse than the KGB!” Solzhenitsyn’s relations with Western media went downhill from there.

* * *

Solzhenitsyn first lived in Zurich, where he could be near his Swiss lawyer Fritz Heeb. In exile, he had all the usual problems of adjusting to new laws, customs, and languages. The shock of leaving his homeland was amplified by the fact that whereas great writers tend to be taken seriously in tyrannical countries, their every word read carefully; in free societies, surfeited with information, they are often ignored or read superficially. After Andrei Sakharov claimed that Solzhenitsyn opposed universal democratic ideals, he was branded a Slavophile fanatic and religious zealot. As Daniel J. Mahoney points out in the Foreword, however, Solzhenitsyn’s views on Russia were reasonable, and his religious principles were moderate. Solzhenitsyn argued that a cosmopolitan democracy would have no cultural roots and would therefore fail. He maintained that democracy is a learned behavior. Nations emerging from tyranny should decentralize, he argued, so that people can practice the art of self-government at the local level. His model was the government of a Swiss village. He never advocated fanatical spiritual devotion, but asked only that people not cast off religious beliefs in favor of mindless materialism.

Far from being a political extremist, Solzhenitsyn showed extraordinary prescience when analyzing what later would be called the post-Communist world. He predicted that Sakharov’s dream of establishing a peaceful global community was not feasible and that globalization would eventually create nationalist movements. He worried that the collapse of Communism would rekindle ethnic hatreds long kept in check under Communist tyranny. He feared that the collapse of the Soviet Union might result in a war between Ukraine and Russia. He foresaw that nations emerging from Communist rule would have long, difficult transitions to functioning civil societies. Free and democratic government depends on citizens’ voluntarily obeying the rule of law, but citizens did nothing freely under Communism.

Even after his family joined him in Europe, Solzhenitsyn was “untethered,” as he put it. He feared that a longing for peace had led European nations to accommodation with tyranny, making his security there precarious. He needed to find a safe place to live, away from the crowds of reporters, visitors, celebrity seekers, and, of course, beyond the KGB’s clutches. He required a home where family life was feasible, but where the solitude required for the artistic process was also possible. After two years in Zurich, he decided to move. He traveled throughout Europe for the first time in his life, as a tourist. He also looked for a new home, almost settling in France because he found it less well organized and neat than Switzerland. He considered moving to Norway because of its Russian-like weather. But he was fearful of “how sharp the Soviet Dragon’s teeth” were in all of Europe, finally deciding rural Vermont would be safest.

* * *

During these travels, he discovered that, although free societies are certainly better than totalitarian ones, some Westerners exercised their liberty irresponsibly. People threw themselves into the pursuit of pleasure or the accumulation of wealth. Others mistook passivity in the face of evil for moral rectitude. Solzhenitsyn reminded people that having the right to do something does not make it right. What troubled him most was that elites trivialized the civilizational struggle between freedom and tyranny.

One of the most touching parts of the book is Solzhenitsyn’s dismay at not comprehending the legal and cultural norms of the West. “In the USSR, that hard and unforgiving land,” he explained, “all my steps turned into a series of victories. Yet in the West, with its limitless freedom, everything I did (or did not do) ended up in a string of defeats. Did I ever fail to make a mistake here?”

Under despotism, Solzhenitsyn could readily spot an informant or a self-seeking careerist. In the West, where almost everyone seemed forthright and earnest, he put his faith in people who let him down or took advantage of his inexperience. It was difficult for him to tell whether the people outside his house were admirers, reporters, or KGB operatives sent to kill him. His books were often poorly translated, and translators hardly ever met deadlines. He had little understanding of international copyright laws, which resulted in suits against Solzhenitsyn for the international rights to First Circle, Gulag Archipelago, and Oak and the Calf.

Solzhenitsyn donated all the royalties from The Gulag Archipelago, which sold more than 30 million copies, to a fund that supported victims of Communism. The kind Swiss lawyer whom he trusted failed to file proper documents, however, and the Swiss charged Solzhenitsyn with tax evasion. Though the authorities were aware he had received no royalties from his book, they served him with a bill for $11 million in today’s currency. The matter was resolved only after a yearlong struggle with the Swiss bureaucracy.

* * *

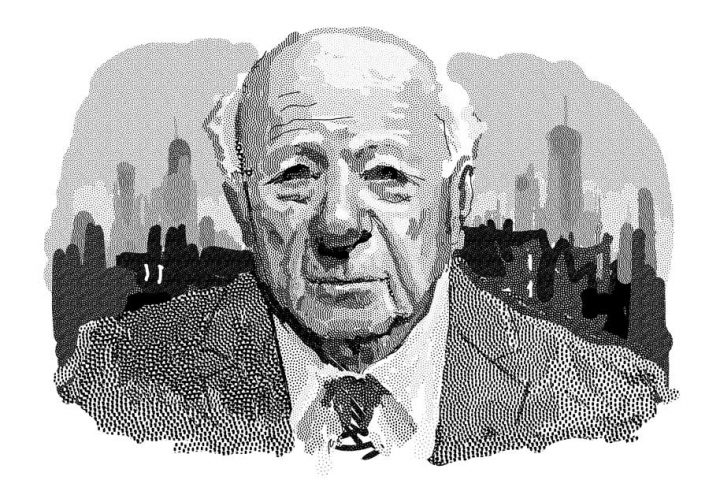

His notoriety in exile peaked with his Harvard Commencement Address in 1978. He warned the West about its loss of courage in the face of totalitarianism, dependence on legalisms rather than common-sense moral codes, belief that material comfort can lead to happiness, inclination to adopt trendy fashions of thought, shallow presentations of events by the media, and its overall loss of spiritual grounding. After Harvard, the popular image of Solzhenitsyn became that of a dour prophet railing against the modern world. Between Two Millstones shows that he was primarily an author with an exceptional knack for making characters come alive on the printed page. In this memoir, he emerges from the shadow of his public persona. Instead of the “slightly balmy nineteenth-century Russian mystic” that President Jimmy Carter described, we see a thoughtful, witty, ironic, sensitive man struggling to adapt to a new culture. He is torn between the weight of fame (legions of people want to admire, damn, or meet him) and his longing for the unencumbered life of a writer. He is at war with his critics, defending himself against charges that he is a Slavophile, unable to understand ideas outside his cultural milieu. He is at war with Russian émigrés who blame their homeland’s ills on a defective national character rather than on Marxist ideology.

Solzhenitsyn was not without some fascinating eccentricities. He decided not to settle farther north because he thought Canadians were too nice and lacked spirit. He hated New York because the “inhuman skyscrapers” cut people off from the natural world. He disliked restaurants because they make eating food a performance. For most of his life, he took no days off: his collected works run to 20 volumes. He was a polymath, an able scientist, and mathematician who devoured literature in many languages. He had a sardonic wit, as when he relates how he tried to discuss the civilizational struggle between freedom and tyranny, “On Sunday I appeared on Meet the Press. In the half-hour we were on the air they managed to interrupt us with a bra commercial.”

For readers who seek to understand one of the pivotal geniuses of 20th century, Between Two Millstones is a treasure. As he predicted on the night he was exiled, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn returned to his homeland, living outside Moscow from 1994 until his death in 2008.