For a while now, people like me, Ian Grigg and David Birch (top rank blockchain/payments experts) have been moaning on Twitter about how anti money laundering and Know-Your-Customer rules, despite being developed in good faith, have started to backfire on the system.

Rather than curbing criminal financing, in many instances all they have done is add bloat and cost to the banking sector, while making it even harder for the disenfranchised to get banking access.

Meanwhile, multi-billion dollar-worth money laundering operations like Wirecard have been able to run unchecked regardless.

A key part of the vulnerability is that KYC/AML does little to solve for the problem of corruption. Garbage in, garbage out can still go on. So if you have the whole German institutional state in your pocket you can proceed unhindered.

But there is another issue that has also been worrying me for some time. It relates to the qualifying conditions for being cut off from financial services under the AML regime in the first place. One of those conditions is being judged to be involved in terrorist financing by the state. Or even to be suspected of it by your bank or payment provider service.

But it’s just how broadly and potentially subjectively the counter terrorism clause can be applied, which is the problem.

In the UK there is a clear definition under the 2000 Terrorist Act of what qualifies as terrorism:

Even so, there is still room for disagreement. Is an anti vaxxer a terrorist because he is a danger to public health? Not everyone would agree. A blanket rule seems too blunt to be able to make that assessment.

In the US, the domestic terror component in the Patriot Act, turns the issue into an even more subjective assessment (my emphasis):

Section 802 of the USA PATRIOT Act (Pub. L. No. 107-52) expanded the definition of terrorism to cover “”domestic,”” as opposed to international, terrorism. A person engages in domestic terrorism if they do an act “dangerous to human life” that is a violation of the criminal laws of a state or the United States, if the act appears to be intended to: (i) intimidate or coerce a civilian population; (ii) influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or (iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination or kidnapping. Additionally, the acts have to occur primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States and if they do not, may be regarded as international terrorism.

Which is why the ACLU has said the following for a long time:

The definition of domestic terrorism is broad enough to encompass the activities of several prominent activist campaigns and organizations. Greenpeace, Operation Rescue, Vieques Island and WTO protesters and the Environmental Liberation Front have all recently engaged in activities that could subject them to being investigated as engaging in domestic terrorism.

Herein really lies the problem. Organisations that are connected to any form of civil disobedience, could in theory be deemed terrorist organisations fit for defunding.

Given the long history of civil disobedience being used in America to effect positive social change, whether for civil rights or environmental causes, this has major political — and potentially authoritarian empowering — side-effects.

The rule is also partial to immense political gaming.

Don’t like that the people are forging a powerful political campaign for x or y cause? Just infiltrate their movement with a few destabilizing agent provocateurs, turn it violent, and hey presto – the group gets classified as a terrorist organisation with all its political offshoots defunded. It can never rise as a legitimate political force.

Luckily! The FATF, the very organisation that guides the implementation of AML/KYC rules has spotted the unintended consequence problem.

Check out section four here (my emphasis):

The FATF has not previously systematically studied this issue. Situations have arisen in the course of FATF evaluations concerning the interaction between the FATF Recommendations on combating TF (particularly R.5 and R.6) and due process and procedural rights (e.g. to legal representation, fair trial, and to challenge designations, etc.), which have been considered on a case-by-case approach as they arise in specific country contexts. In addition, the FATF has also been made aware of instances of the misapplication of the FATF Standards, which are allegedly introduced by jurisdictions to address AML/CFT deficiencies identified through the FATF’s mutual evaluation or ICRG process, potentially as an excuse measures with another motivation. This information often comes as a result of stakeholder input or when the attention of the FATF or its members is drawn to a particular issue, such as when another international body is reviewing legislation or actions are taken by national authorities. Analysis in the stocktake has therefore focused on the due process and procedural rights issues most often arising in evaluations or feedback.

The stocktake reviewed the specific provisions relating to due process and procedural rights in the FATF Standards, which include multiple references to relevant human rights and fundamental principles of domestic law (which embed human rights in national legal systems). It noted that there has been an inconsistent consideration of due process and procedural rights in the mutual evaluations conducted to date, though as with other unintended consequences this is not a core purpose of FATF evaluations. For example, most FATF MERs have not included analysis of this topic either in Chapter 1, in the chapters analysing effectiveness, or in the Technical Compliance Annex. The topic of possible infringements or abuses and their link to the FATF Standards has been largely omitted from MERs, even in cases when concerns about such issues have been widely reported by credible and reliable sources.

The analysis explores a number of ways in which misapplication of the FATF Standards may affect due process and procedural rights, including:

- excessively broad or vague offences in legal counterterrorism financing frameworks, which can lead to wrongful application of preventative and disruptive measures including sanctions that are not proportionate;

- issues relevant to investigation and prosecution of TF and ML offences, such as the presumption of innocence and a person’s right to effective protection by the courts;

- and, incorrect implementation of UNSCRs and FATF Standards on due process and procedural issues for asset freezing, including rights to review, to challenge designations, and to basic expenses.

The biggest issue for me is the one about due process.

There is a difference between arresting civil disobedience-orientated protestors and judging their actions on an individual basis under the habeas corpus regime, and applying blanket defunding measures to everyone involved in a protest movement on the assumption that absolutely everyone is guilty of criminal or terrorist intent.

This is no small thing. This is what the foundations of western enlightenment democracy are built on.

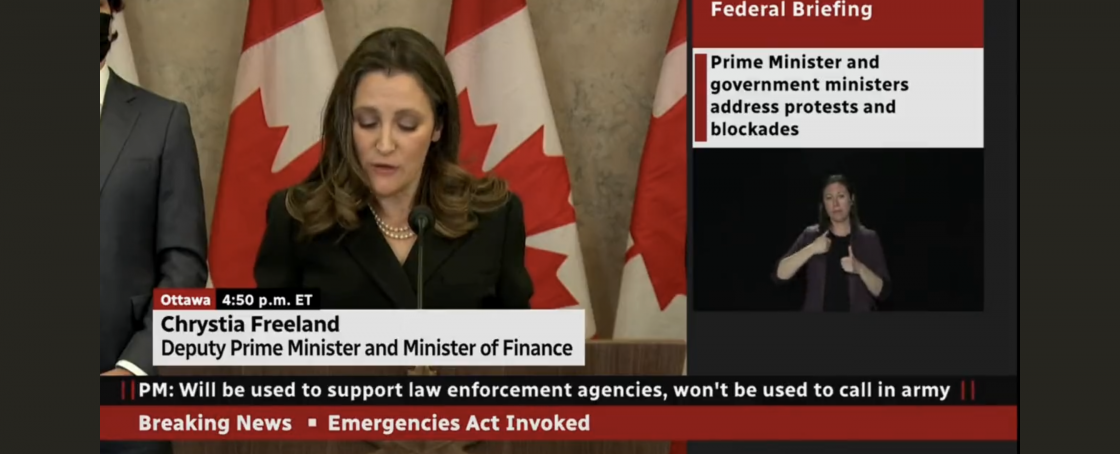

This is why Trudeau is standing on dangerous ground.

BTW – this is another one of those stories that there wasn’t much appetite for printing in the non blog section of the New Agenda FT. I first brought it up as a vulnerability when AML/KYC rules first began being cited as the justification for defunding “problematic” vloggers on platforms like YouTube, some five years ago or more.

Here’s some further reading on the issue from Simon Lelieveldt.

10 Responses

Relevant update here.

https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/06/financial-sector-overcompliance-unilateral-sanctions-harmful-human-rights-un

The Special Rapporteur on the negative impact of unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights, recommends to banks and other financial institutions and service providers to act in the spirit of that resolution, and avoid over-compliance with sanctions when it impacts human rights. She recommends them to align their compliance with human rights policy, and to comply with their responsibilities under the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights[2] and General Comment No. 24 of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural rights.[3] She further recommends to states to act in line with their obligations under the international law treaties they have ratified to protect human rights by preventing financial and other private companies under their jurisdiction from over-complying with sanctions, and to adjust regulatory requirements for the financial sector where necessary.

thanks for that

“Given the long history of civil disobedience being used in America to effect positive social change, whether for civil rights or environmental causes, this has major political — and potentially authoritarian empowering — side-effects.”

You need to be careful using “positive” civil disobedience as an excuse for actions which are fundamentally trying to overturn the democratic system. Like seizing the capitol and the actions of those on the far right, KKK, Aryan nations etc who also believe they had the right to do what they liked.

You can’t pick and choose your civil disobedience. You are either accepting of it or not. The point of civil disobedience is to intiate discussion with leadership. Engaging with the critics usually makes sense. At the extreme end look at Ireland.

Meh. Due process only benefits those who can hire a lawyer. It most benefits those who can hire a high-priced lawyer, who can turn “due process” into “undue delay.” I do agree, however, that imputing the actions of individuals to organizations or other individuals is a very difficult problem in modern law. But that, too, cuts both ways.

Especially like the last paragraph