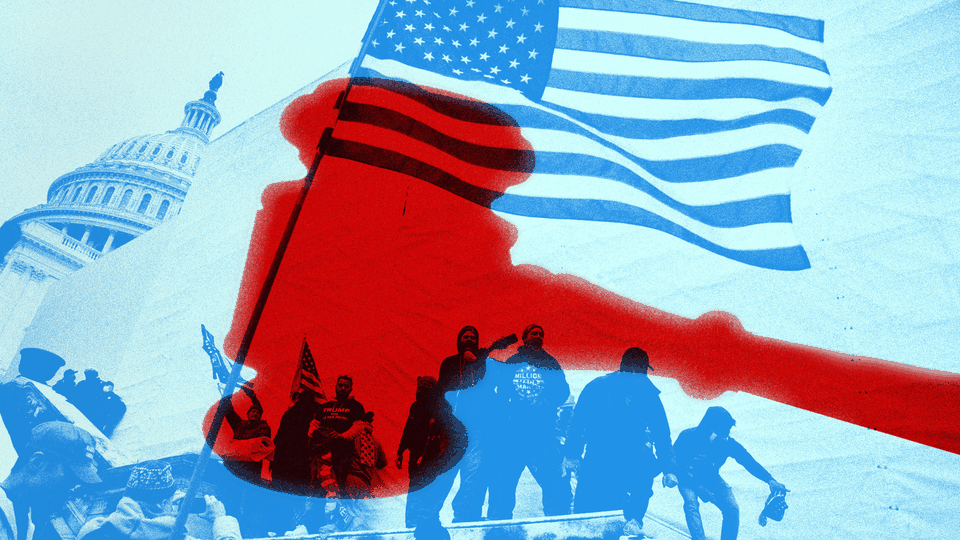

A Federal Judge Just Told the Truth About Trump

Judge David Carter sliced through rhetorical nonsense and confirmed what everyone saw on January 6.

“The illegality of the plan was obvious.”

Attorneys, as a class, are not typically well regarded for their writing; not for nothing do we call sentences that are incomprehensible, jargon-laden, or obfuscatory “legalese.” Yet what makes an order from Federal Judge David Carter today important is less its legal ramifications than the simple clarity of the view it offers of former President Donald Trump’s attempt to steal the 2020 election.

Carter’s order continues: “Our nation was founded on the peaceful transition of power, epitomized by George Washington laying down his sword to make way for democratic elections. Ignoring this history, President Trump vigorously campaigned for the Vice President to single-handedly determine the results of the 2020 election. As Vice President Pence stated, ‘no Vice President in American history has ever asserted such authority.’ Every American—and certainly the President of the United States—knows that in a democracy, leaders are elected, not installed.”

The subject at hand in Carter’s order is whether John Eastman, the conservative legal scholar who masterminded (if we may use the term) the paperwork coup, could shield his emails from the House Select Committee investigating the January 6 insurrection. Carter’s short answer is: no. He ruled that most of the messages must be turned over, though he concluded that the committee is not entitled to a few of them. The order is likely to get more attention than the average procedural battle over the House committee’s work, thanks to the reasoning Carter used to reach his conclusion and the way he phrased it.

Eastman argued that the documents in question were subject to attorney-client privilege or similar work-product protection, and therefore should not be shared. The committee’s lawyers argued, in part, that Eastman was not working as Trump’s attorney at the time—but Carter rejected that claim. The attorney-client privilege, however, cannot be used to hide violations of the law, or every clever aspiring or active criminal would just keep lawyers around to keep their communications confidential. (Some do try this, though.)

This is known as the “crime-fraud exception.” If the plaintiffs can convince a judge that documents were likely involved in the planning or commission of a crime, then privilege doesn’t apply. The standard for this is “a preponderance of the evidence”: In other words, it is more likely than not that a crime was planned or occurred. This is a common standard in some legal proceedings, such as many civil suits, but is much lower than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard used in criminal trials.

Carter was convinced. The result is headlines such as “Judge: Trump Likely Committed Crimes Related to Election” (Associated Press) and “Trump Likely Committed Felony Obstruction, Federal Judge Rules” (Politico). These headlines aren’t wrong, and they aren’t actively misleading, but they might give the wrong impression. The ruling doesn’t mean that Trump is likely to go to jail soon, much less face charges. For that to happen, the Justice Department would have to decide to pursue charges, obtain an indictment, and win a conviction in court, using the reasonable-doubt standard. As I have written, the hope that the judicial system can solve the political danger that Trump poses has, by now, been revealed as deeply naive. Although it might be cathartic for Trump’s critics to see a federal judge saying that Trump probably committed a crime, it’s fairly irrelevant as far as personal accountability goes.

But Carter’s order is valuable because it slices through rhetorical nonsense and confirms that what everyone saw happen after the election did, in fact, happen. Although the format limits the judge to dissecting Eastman’s own arguments, the rebuttal works as a response to similar claims by Trump, his henchmen, and his allies in the media.

For example, Eastman argues that there was widespread popular belief in fraud in the election; as Carter notes, this is largely because “President Trump and Dr. Eastman helped foster those public beliefs and encouraged state legislators to question the election results.” Carter bluntly points out that Trump must have known that trying to disrupt the January 6 vote count was wrong. He points to the many cases where Trump had been told he’d lost the election, as well as the more than 60 courts that had thrown out fraud suits by January 6. “President Trump and Dr. Eastman justified the plan with allegations of election fraud—but President Trump likely knew the justification was baseless, and therefore that the entire plan was unlawful,” Carter writes.

Of course this is all right and true. Everyone saw Trump insist that the election was stolen, heard him try to twist Brad Raffensperger’s arm, read his tweets pressuring Vice President Mike Pence to derail the January 6 count, and saw his speech in public that day. As is often the case with Trump, the worst of the behavior is right out there in the open. Yet in the time since, Trump and his allies have thrown up various attempts at confusing the issues: continued claims of fraud, attempts to justify the legality of the paperwork coup, puerile insistence on separation between the president and the mob.

Trump is fond of gaslighting his way out of trouble; last week, he filed a lawsuit alleging that the 2016 collusion between his campaign and Russia—something we all saw—was a racketeering hoax. All too often, this tactic works in public discussion, where nearly half the population is predisposed to believe Trump, and where the press seizes on and prizes debate rather than conclusions, even when the facts are clear.

Although the justice system has not provided the comeuppance that many people want for Trump, judges have also been far less likely to accept this jive than the rest of the public. Court proceedings, unlike cable-TV panels, have to nail down facts and eventually come to conclusions. Thus the several dozen election-fraud suits that were shut down; thus Trump’s inability to shield his tax returns; thus Eastman’s swinging strikeout in Carter’s court.

Moreover, judges have also occasionally managed moments of startling lucidity that can reframe the debate even before the lay public. In November 2019, then–District Court Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson—now awaiting a vote on her Supreme Court nomination—memorably rejected claims of immunity for presidential aides, writing, “Presidents are not kings.” Judge Carter has now provided a similar jolt. Whatever the future of accountability for Trump himself, Carter’s insistence on the head-slapping obviousness of the former president’s wrongness and culpability is a victory for reality.