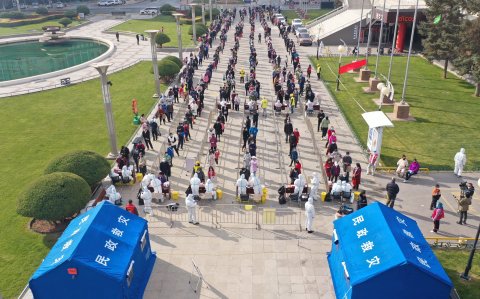

Athletes competing at the Winter Olympics in Beijing got first-hand experience of China's prowess in controlling COVID-19 outbreaks. Unlike the often vague and inconsistent public-health policies of the U.S., Beijing has perfected the art of the lockdown. Athletes were strictly cordoned off from the outside world, required to wear masks and submit to daily tests, and isolated in their rooms upon a negative result.

The safeguards did more than merely protect athletes from infection. They also protected China's newfound reputation as a competent steward of global public health in a pandemic crisis.

The idea that China, less than 20 years since bungling the SARS outbreak, has raised its game to world-class standards might be cause for celebration. A Chinese public-health system that is alert to pandemic pathogens and can bring the best technology and know-how to early warning of new viruses should be reassuring not just to the people of China but to the rest of the world. Yet China's strategy of relying on strict lockdown measures to keep the Omicron variant at bay may not be sustainable in the coming months. And animosity between the U.S. and China raises concerns about the world's prospects for battling future outbreaks.

In the realm of pandemic prevention, cooperation is key. Nations are far better at fighting pandemics when they collaborate than when they go it alone. The COVID-19 pandemic may have hurt the world's ability to fight the next pandemic, rather than improved it, in large part because U.S.-China relations have deteriorated.

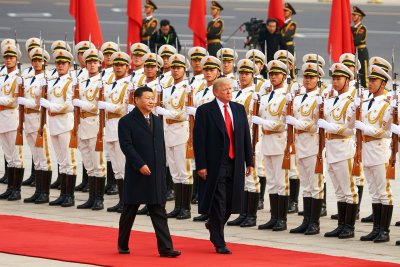

Nerves were already on edge before the pandemic, with the Trump administration's bellicose talk and aggressive stance on trade. Two years of COVID-19 have exposed longstanding rifts and opened some new ones. The debate over the origins of the virus—whether it came naturally from animals or a lab in Wuhan—generated more animosity than information. And the Biden administration refused to attend the Olympics in Beijing over China's human rights violations. For its part, China's president Xi Jinping posed with Russia's president Vladimir Putin in support of his Ukraine adventure.

The pandemic has also soured public opinion on China. The proportion of Americans who view China as an "enemy" doubled in the first year of the pandemic, according to Gallup. Americans supported the Olympic boycott by a ratio of two to one, and nine out of 10 consider China to be a "competitor" or "enemy," according to a Pew survey in January. It's not just an American thing: similarly unfavorable views on China showed up in nearly every major country in Pew's attitudes survey last year. Although Chinese views are harder to measure, anecdotal evidence suggests that anti-American nationalism is on the rise.

Distrust of China, and vice versa, does not bode well for global public health. China's leaders have some reason to think that the next time a pandemic strikes, they won't need the West's help. The pandemic has made it more difficult to argue that China has something to learn from the West about infectious diseases. While the U.S. has just passed the grim milestone of 900,000 deaths from COVID-19, China has kept its death rate below 5,000, at least officially. It developed two vaccines and administered three billion doses, enough to inoculate all of its 1.4 billion citizens.

Dr. Jennifer Bouey, an epidemiologist and analyst at the RAND Corporation, has studied China's progress in improving its public-health and disease-surveillance systems for the past several decades. Public-health officials in the two nations had developed an unprecedented collegiality that made it easy to put their heads and resources together to battle new outbreaks. But with mutual distrust on the rise, that ability is evaporating.

"There was an increase in collaboration between the two countries, particularly in the last 20 years," she says. "That phase now looks like it's over."

Forgetting the Lessons of SARS

The golden age of U.S.-China cooperation in public health started with the SARS crisis in 2002. Although China mishandled the epidemic in the early days, it quickly recovered and went on to forge a close working relationship with public-health officials in the U.S. and elsewhere–progress that has diminished since the COVID-19 pandemic.

When SARS was first detected in Guangdong, in southern China, in November 2002, the provincial government sent a team of investigators, including some from the central public-health authorities in Beijing. But China did not publicly acknowledge the outbreak until March, when cases had surfaced in several countries of Southeast Asia and as far away as Canada. Beijing didn't muster a significant response until the World Health Organization confirmed 791 cases and 31 deaths on March 27, five months after the virus was initially detected.

Beijing reacted by establishing a national command center, firing more than 1,000 officials and implementing lockdown measures. Although SARS was much more deadly than SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 virus, it turned out to be far less transmissible. By the end of June, the WHO declared China SARS free.

China was criticized for its delayed response, which, had the virus been more transmissible, could have put the world in considerable peril. After the crisis subsided, however, it invested billions to shore up its public health system and infectious-disease reporting. It also moved to strengthen relationships between its public-health officials and those in the U.S. and other nations. It accepted help from U.S. experts in fashioning its own facilities, which were modeled on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). China's CDC took a coordinating role in the nation's response to emerging threats from infectious disease and, in turn, supported branches in the provinces and cities throughout China.

In 2014, Beijing established a National Influenza Center, which grew to include more than 408 laboratories and 554 hospitals that acted as "sentinels," keeping watch for outbreaks, according to Bouey. It also set up pneumonia centers that specialized in the symptoms of coronavirus infections of the lungs and upper respiratory system.

The new system got its first major test in 2013, when about 420 people were sickened with H7N9, a bird-flu virus, which killed one in five of those infected. Although the virus wasn't very good at jumping from one person to another—most cases involved people who'd come into contact with animals—scientists fretted that a variant would overcome this limitation and spark a pandemic.

The H7N9 outbreak gave China an opportunity to demonstrate its new disease-surveillance chops. It had its technology and clinics in place to identify the virus, and continued to monitor it over four successive waves over several years. It also developed its own vaccine, in case one was necessary to contain the outbreak.

The outbreak came at a time of peak cooperation between the U.S. and China. The U.S. sent experts. A staff of 40 or so U.S. scientists worked in offices adjacent to the Chinese CDC in Beijing, making it easy to compare notes and consult one another over the latest developments. Over the next few years, Chinese scientists earned praise for their close tracking of new cases and for their generous sharing of information and observations with other public health officials. "For H7N9," says Bouey, "the timing was right."

Then things began to unravel. After the assassination of a U.S. diplomat in Benghazi, Libya, and the subsequent hearings on Capitol Hill, the U.S. State Department. tightened security, recalling the CDC experts to the embassy in Beijing, where contact with their Chinese counterparts was more constrained. "That was the beginning of the loss of trust," says Bouey, "not because of the health issues but really because of geopolitics."

This close working relationship also took a hit when both nations scaled back their pandemic-defense spending. The Trump administration eliminated the office of pandemic preparedness in the White House. Beijing reduced the staff of its CDC from more than 11,000 to 2,120, just before the COVID-19 pandemic struck.

Pandemic Rifts

Exactly when the first case of COVID-19 arose is the subject of some debate, but it probably occurred on December 1, 2019, in Wuhan, according to Yanzhong Huang, a public-health expert at Seton Hall University, who wrote an account of the early days of the pandemic for the Council on Foreign Relations.

Huang wrote that, according to Chinese state media, Dr. Zhang Jixian, a physician at a provincial hospital, noticed that patients were coming in with an "unknown pneumonia." The hospital informed the district CDC office. A few days later, as Zhang saw more patients, she grew concerned that the virus might have been transmitted from person to person, though it was also possible that infections were acquired from animals at the Huanan Seafood Market. She alerted the authorities for a second time on December 29 and sent six patients to a hospital for infectious diseases. The next day, according to Huang's account, the Wuhan Health Commission sent an urgent message to Zhang's hospital calling for "effective treatments."

Samples from these early patients were promptly submitted for tests, which quickly confirmed that 80 percent of the new coronavirus's genetic material was similar to that of the original SARS virus. Chinese scientists worked to isolate the virus and sequence its genome, and shared this information with the WHO, the U.S. and other nations.

"The disease surveillance system appeared to work at the time," wrote Huang.

Almost immediately, however, the attitude of local authorities changed. The provincial government made decisions that left Western public-health experts perplexed. On December 30, by Huang's account, the Wuhan Health Commission sent out a notice that "no units or individuals shall release treatment information without approval." Two doctors who shared information in apparent violation of the order were admonished, and one was called in to local police to sign a statement admitting to spreading falsehoods.

On January 1, the Hubei Provincial Health Commission issued orders that ran counter to the kind of transparency a Westerner might expect in a public-health inquiry. Rather than quickly disseminating information about the new pathogen its disease-surveillance system had identified, it ordered a halt to testing of new samples, the destruction of all previous samples and tight secrecy on any information obtained about the virus. It also disinfected the Huanan Seafood Market, destroying evidence that might have been useful in determining how the virus first arose.

For the next several weeks, information from China about the outbreak slowed to a trickle. The provincial government seemed to underreport cases and accounts, at least compared to what scientists outside of China later estimated. No public statements about person-to-person transmission appeared until January 20. It seemed that China, despite its investments in public health, was making the same mistakes it had made during SARS nearly 20 years ago.

From the vantage point of Washington, D.C., these actions seemed odd, to say the least. To some, it seemed that Beijing was engaged in some kind of cover-up. The lab-leak theory, which holds that the virus originated in the Wuhan Institute of Virology and escaped, perhaps by infecting a lab worker, expanded into this vacuum of information.

After nearly two years of investigation and debate, decisive evidence either way is absent. Huang, for one, is agnostic about the lab-leak theory. "You can't rule it out," he tells Newsweek. But the lack of information on what China did in the early weeks of the pandemic, and why, leaves much room for speculation. "With China's lack of transparency," he says, "you're free to use your imagination."

Whatever the cause, mounting grievances in Beijing and Washington, D.C., are not helping the cause of global public health. "It's like a divorce case," says Bouey. "It's hard to say whose responsibility it is. But there's mutual dissatisfaction that built up over many years and became an open fight, and that has spilled over to health."

Observing Hierarchy

The SARS experience in 2002 offers an alternate explanation of China's actions in the early days of the pandemic: the top-down structure of China's government may have inhibited Wuhan authorities from reporting information up the line to Beijing.

Between late December 2019 and late January 2020, the CDC in Beijing sent three expert teams to investigate the reports of pneumonia. Neither the first team nor the second team, confining their focus mainly to the seafood market, found evidence of person-to-person transmission as late as January 8. Only when cases started arising in Thailand and South Korea among people who clearly had no link to the Wuhan market did China dispatch a third team to Wuhan. It concluded on January 19 that the coronavirus was indeed being transmitted from person to person.

It's possible that provincial authorities kept Beijing in the dark about what was going on in Wuhan. They were certainly worried about the economic impact of a disease outbreak in the days before the Chinese New Year, when citizens travel to gather in celebration. The understaffed CDC in Beijing relied on provinces and municipalities, also underfunded, to carry out many of the important public-health tasks. Local authorities may have held back information to avoid reproach.

"It's a vertical system: the central government gives orders to the local government," says Bouey. "Information rarely comes the other way. That's not the way it was designed. The local government is supposed to implement what the central government is doing."

It's also possible that the provincial and municipal authorities were indeed carrying out the central government's wishes by suppressing news of the outbreak. In China's closed society, where such communications are not accessible via Freedom of Information Act requests, it is difficult to know.

Whatever the explanation, it seems clear that a lack of transparency in China's political system, as well as its hierarchical structure, constitute more-or-less permanent obstacles to an effective pandemic response. It may be possible in the best of times to overcome these obstacles, but in a situation of mutual distrust, probably not. Fixing flaws in China's disease surveillance capabilities may be a relatively straightforward matter of investing resources in new clinics, personnel and training, but "the political system will be much harder to change," says Bouey.

What will happen next? Public health experts warn that China's policy of relying on draconian lockdown measures to keep the pandemic virus in check has left the nation in a precarious position. Its COVID-19 vaccines provide poor protection against the highly-contagious Omicron variant that is currently on a rampage across the globe. Experts think that SARS-CoV-2, which can carry on circulating in deer and other animals, is probably never going away. To avoid the kind of Omicron spike that much of the rest of the world is experiencing, China will be hard-pressed to keep lockdown measures in place while it administers booster shots to its citizens.

Beyond COVID-19, the ability of nations to keep the world safe from future pandemics may hinge on whether two nations can reconcile their differences.