In this conversation with the sociologist Nikolaj Schultz, Bruno Latour elaborates his analysis of our new climatic regime and presents new ideas on its consequences for political and social theory. With the earth reacting to our actions, we face a cosmological shift that leaves us all divided and lost in space. The quintessential political question of our times is finding a place to land. Globalists continue to believe in the project of modernization, populists flee back to the land of the old while a few escapists simply try to take off to other planets. How to respond? According to Latour, the task becomes reinventing the old socialist tradition beyond the system of production, something we can only do if we retheorize the concept of social class to include a wider array of material conditions of existences than Marx’ definition of class alluded to.

Cosmology and Division

Nikolaj Schultz (NS): In Facing Gaia you try to historically situate our present encounter with an earth suddenly reacting to our actions by comparing two different scientific discoveries.[1] In the seventeenth century, Galileo Galilei raises his telescope to the moon and shortly after concludes that our earth is similar to all the other planets of the universe. Some 350 years later, James Lovelock instead concludes that our earth is dissimilar to all the other planets. What are the symmetries and asymmetries of these two discoveries and what do they tell us about where we are in history?

Bruno Latour (BL): Galileo and Lovelock both try to cope with moving earths but two different kinds. Galileo discovered that the earth was moving around the sun and disturbed everybody by saying so. First, there was the quarrel with the church and, secondly, there were the major consequences his discoveries had on social order. This is well-known from the history of science and because of Bertolt Brecht’s extraordinary play The Life of Galileo. People believed they were in one cosmos before suddenly learning that the earth was moving. They did not know where they were in space and they felt lost—even if the practical consequences of Galileo’s discovery for daily life was close to zero. So, at hand we have a famous discovery with major impacts for physics and astronomy that simultaneously disturbs the whole establishment of the church and the social world.

Now, I contrast this with Lovelock’s similar but different discovery of another kind of moving earth. What Lovelock and Lynn Margulis discover is not simply that the earth is moving but that earth is being moved, to use Michel Serres’s expression.[2] The earth is reacting to the actions of humans. This new sort of movement of the earth is immensely more important, not least in terms of consequences for the social order and thus also more disputed. So, with a gap of three hundred years, we have two discoveries of moving earths and what interests me is that they both bring along extraordinary changes in cosmology and in understanding of space. It is another powerful example of a question which has interested me for forty years, namely the link between science and society, between cosmology and social order. While Galileo’s discovery marked the beginning of modern cosmology, I see Lovelock’s and Margulis’s discoveries as marking the end of modern cosmology. Right now, when we here about their discovery that the earth is being moved, we find ourselves in the same shoes as the people who in 1610 were worried about Galileo messing up their cosmology by proving that the earth was moving. We are as lost as they were.

NS: So, to talk with Alexandre Koyré, if Galileo took us from the “Closed Cosmos to the Infinite Universe,” then Lovelock is bringing us back from the infinite universe to a closed cosmos on earth.[3] Why has the figure of this return to earth, Gaia, been so misunderstood?

BL: Most importantly because it was understood trough a wrong idea of space. Gaia was immediately associated with the idea of the globe and with the idea of the earth as an organism. This meant it was quickly used by biologists and New Age people to return to the old, Greek idea of earth considered as one big animal. But this was not what Lovelock was interested in. Instead, he was interested in how life forms—including bacteria, vegetation, insects, and others—had provided so many changes in the chemical circulation of the atmosphere that it became impossible to understand air, water, mountains, or plate tectonics without taking into consideration the dynamic agencies of these life forms. With the help of his instruments, Lovelock was studying pollution and had realized that pollutants were able to spread everywhere on Earth. This made him intuit that what modern industry was doing perhaps had been done for billions of years by all life forms on Earth. He meets Margulis who studied the consequences bacteria had on the atmosphere, climate, rivers, mountains, and together they arrive at this extraordinary entity called Gaia. An entity with nothing in common with the idea of the earth being alive as an organism. Instead, it is an argument about the ways life forms continue to transform their own conditions of existence to the point where they engineer the whole surface of the earth.

NS: So, the fundamental consequence of Gaia is that entities make up their own environments. This not only means that climate is the historical result of agencies, it also means that space itself is the offspring of time. With Gaia, space is not in the background, space is continuously constructed by dynamic life forms. Why is this difficult to understand cosmologically?

BL: Not least because of the cartographic tradition, invented at the time of Galileo. Cartography gave us a sort of taken-for-granted definition of space as a frame inside which objects and people reside. With this definition of space, you cannot see how space itself is constructed by the agencies of life forms. With this gaze, you miss how life forms are not in space but that they make space. One example is how bacteria produce the oxygen of the atmosphere that all life forms breathe. Bacteria are not in the frame, they make the frame. This you cannot see if you approach space cartographically. If you approach space from the view of the globe, or as a map, you remain stuck inside a frame, with difficulties understanding what life is. These difficulties have burdened biology and ecology since the seventeenth century.

With Gaia the situation is reversed. The trick of Lovelock and Margulis is to say, “If there is an earth, soil, and sea, it is because life forms are producing their own environment.” Life forms are not sitting in the environment, they produce the environment. In biology, Margulis’s ideas and her notion of holobionts are becoming mainstream now. Today, everybody knows that our bodies are made of microbes, for example. So, the idea that we are seized and maintained by the agencies of life forms is beginning to become common sense. The amusing thing is that this idea of space as the product of agencies is an old actor-network theory argument that we developed completely separately in sociology.

NS: What are the political consequences of this concept of space? Previously, you have conceptualized this spatial or cosmological shift with the notion of a new climatic regime.

BL: Like Galileo, Lovelock is not interesting for his politics. What I am nonetheless interested in is the political consequences of being lost in space after the discovery of Gaia. This is somehow what I try to map very grossly in Down to Earth.[4] My argument is that what we all have in common is no longer moving forward trough progress but that we are lost in space. What we all have in common is no longer having an exact idea of where we are in space or on what soil or land we reside. And I think this shows clearly in the political disputes of today.

First, by what is normally referred to as populist movements and their questions of “What are our borders and what are the people inside our borders?” Questions posed all over Europe and, of course, most vividly with Brexit. Secondly, it shows with those who say “Let’s go on,” “Business as usual,” “Let’s maintain the modernist tradition of progress.” The ideal of globalization, if you want. Both these positions are simply affects asking where we are, on what soil or land we reside. Now, the problem is that both these positions are too abstract in terms of material existence. The land the populists wants to go back to—The England of Johnson, The Italy of Salvini, The France of Front National—are not real countries. They are imaginary versions of what would have been the land years ago. But the land of the globalists is just as imaginary, as they imagine that the earth will accept infinite modernization. So, we are lost in space.

NS: So, politics is now ordered by the question of land, but we are all lost in space because none of the political territories that modernity offers us have any ecological or economical fundament.

BL: Exactly. Look at the example of Brexit, for me a great experimentation of territorial redescription. It started with an imaginary space based on ideas of identity and borders. Three years later it is a complete mess. The English learned day by day, bit by bit, what they were actually depending on as a territory—dependencies always transcending the nation state. If you leave the EU, you will be in trouble getting medicine, fresh food, then your labor force will have bad protection of rights and so on. So, one talks about identity and about walls, but slowly you realize that you do not only depend on identity but more importantly on a long list of other conditions of existences. Our ignorance about what makes our countries thrive is immense. This is what I try to allude to when I say that we are spatially lost.

NS: Yesterday in Paris, you attended the defense of French philosopher Pierre Charbonnier’s habilitation.[5] One of his arguments is that there is a disconnect between where the moderns think they live and the territory they actually live off. How is this connected to the current spatial confusion? Why the difficulty of understanding that to have politics you need to have a land and a people corresponding?

BL: Yes, there is a disconnect between the two sorts of land that we inhabit. On the one hand, there is the land from where we have our rights—the nation state—which is territory that we understand ourselves as living in. On the other hand, there is the land we live from, which is the territory where we get our resources. We sort of know these two territories are connected, but because of the material history of the Moderns—first the colonies, then the discovery of coal and later oil—they have divorced. So, if people have lost their sense of space, it is because of this divorce that has made it difficult for people to describe the world out of which they get their prosperity and the entities that allow them to subsist. And what Charbonnier investigates is simply how this disconnect becomes bigger and bigger ever since the “discovery” of America.

In one chapter, there is an interesting simile to understand the argument and its relevance for political ecology. In the beginning of the nineteenth century, Johann Gottlieb Fichte wrote a book answering to the English project of liberalism, arguing that in inventing the global world the English were completely hypocritical.[6] They pretended to be civilized and tolerant while simultaneously exploiting the whole planet. If Germany wanted to be tolerant, Fichte said, they would need to close down their borders, forbid commerce, and instead juxtapose the land out of which they lived with the land that gives rights to their citizens. Fichte probably did not imagine this to be possible even in the nineteenth century, but it is a fine description of a sort of utopia, where the legal country is reconciled with the material country.

I think this is a good way of grasping our current situation. Because, in fact, political ecology has nothing to do with green stuff or nature. It is about how the new, moving earth forces everybody to ask again the question of what to subsist on. This question of subsistence is a main feature of what I call the new climatic regime. Everyone is simply trying to find out which land to live off and live in. This is also why the Trumpists are climate deniers. You study that yourself, namely the question on how some are saying: “We don’t share the same earth as you.”[7] Something impossible to reconcile with modernism because modernism was supposed to be the progress of all—even if it really wasn’t.

NS: Yes. It is difficult to believe in modernism when you see a picture of Elon Musk’s Tesla sports car floating around in outer space. This did not look like the progress for all—this was progress or emancipation for the wealthy few. And when you look at how other Silicon Valley tech billionaires are trying colonize Mars, then it certainly does not look like modernism either, as the classic question “Is there life on Mars?” is rephrased from a civilizational question into a question for the one percent who try to escape Earth. This is the ideological essence of what you have previously called offshore politics or planet exit: the escapism of the earthly, material limits by the few.

BL: With a lot of money put into it . . .

NS: Lots of money and lots of technology. For these elites it is a case of deus ex machina, and as techsters they are God’s chosen few. It is definitely not a coincidence that the wildfires in California never reached Silicon Valley—and with the prospect of ecological, civilizational collapse they take off and go to Mars. The problem is that you rather quickly find out that Mars is uninhabitable. It is not a very nice up there. So, the tech billionaires shift from planet B to plan B and invest in luxury climate-secured escape bunkers in places like New Zealand, so they can escape civilizational collapse. It sounds anecdotal, but it has been studied in detail by investigative journalists.[8]

BL: So, they hedge their bets, one on Mars and one in New Zealand. How many people are we talking about?

NS: Exactly. Crushed under the weight of the new moving earth, they choose to escape and leave the rest of us behind. They do not live in the Anthropocene they live in the Misanthropocene. Steve Hoffman, the billionaire founder of Reddit, estimates that around fifty percent of the Silicon Valley tech elites have bought escape property around the world. Escape bunker property for the ultrarich has become a billion dollar business.[9] The interesting thing is that it is not even secret, even if it sounds like a neo-Balzacian conspiracy theory when one says that the rich are escaping the planet during nighttime. They actually say so themselves. Yet, it is not an unproblematic move for the rich. A lot of things could go wrong: How do you make sure that your security guards do not turn their weapons against you? Are you supposed to bring the family of the pilot of your private jet when you escape? A lot of questions arise, but it is still better than “staying with the trouble,” as your friend Donna Haraway would say.[10]

BL: But they are not climate skeptics; they are deniers, right? They recognize that there is a planetary danger?

NS: Yes, that is exactly why they take off. Again, climate denial arises not despite the fact that the climatic mutations are real, it arises because the climatic mutations are real and because the price of solidarity is too high to pay. It is the same with Trumpism. These are just the people that take the extreme consequences and choose to leave.

BL: But how do they cope with the fact of being alone and not following the old logic of modernism? How do they cope morally with leaving behind the rest of us? They must sort of reinvent themselves as atomized agents.

NS: That is what should to be studied now. If we could describe the material conditions of existence and the moral economies of these exiters and compare them with those who are stuck behind deprived of habitable territory, we would probably have a better grasp on tomorrow’s class struggle, a struggle over territory and not over the means of production.

BL: When Musk sent his Tesla into space, he said that it was “silly but fun.” The space adventures of the twentieth century were certainly not silly and fun, they were part of a progressive modernity. Seeing space adventure becoming a caricature for just a few people is very shocking. So, at this moment, I think we are exactly at a place where we are literally living on different planets. One of these is the modernist, globalist planet; the other one is the identity, localist planet; and the third is the escapist or exit planet that you study. We are completely divided about which planet or which land on which we live. This is what I try to show in Down to Earth.

NS: Yes, when Musk said that it was “silly but fun” it was good proof that modernity was dead. But we only capture the dividedness you speak about if we remember that these people are very serious about escaping. They put billions of dollars into it. And, somehow, this move of escapist ideology was not a big surprise. Only a few months before, Donald Trump took America out of the COP21 Agreement. What did he do just after? He announced that he was going to “Make America Great again . . . on Mars.”

Class and Description

BL: The question is how to respond to this division of space. Here, I want to go back to what we spoke about before. As Charbonnier shows, the question is now about how to restart the socialist tradition. A tradition that was in fact always interested in the question of the divide between the land, the industry, and the legal framework in which people live. One can even say that socialism was about this disconnect. Yet, it is also true that socialism never succeeded in connecting with ecology. For this reason, Charbonnier’s hero is the same as mine. Karl Polanyi was one of the few in the socialist tradition who articulated the the idea that both the labor force and the land resists production. In The Great Transformation he maintains that it is not a question of production but of what I call a processes of engendering, the ways in which things are brought to the world.[11]

This is the connection I am interested in. Can we, within the socialist tradition, rearticulate the questions concerning ecology as questions of existence, of survival, of generation, of reproducing, of giving birth and of losing territory? As a philosopher, I see the first contours of what we have been calling geosocial classes, a notion that would perhaps allow us to redo for the present situation what the socialist did fairly well until the 1950s and the beginning of The Great Acceleration. This would allow us to reconnect the land that we live in and the land we live from, as well as to connect ecology with socialism within the framework of politics as usual. But I gave you the task of finding these classes. How would you approach the question? What would be a good definition of geosocial classes?

NS: I think your intuition in Down to Earth is correct. These are not classes defined by their position in the production system; they are classes defined by their territorial conditions of survival, their material conditions of existence or reproduction. Defining geosocial classes means taking the cosmology of our new moving earth serious when approaching the social question and use it to redescribe social classes in a way that extends their Marxist definition. While social classes were defined by their ownership over the means of production, geosocial classes are defined by their dependence on a wider array of material conditions of existence that allows social groups to survive or thrive. If we had such a definition of classes, we could delineate a people corresponding to the new climatic question of the twenty-first century, and to geohistory, in the same way Marx made a people correspond to the social question of the nineteenth century and to social history.[12]

The terribly difficult question is how to map this empirically. First, it would be necessary to define the territory on which different collectives live, by describing what entities or actors different social collectives depend on to reproduce. If we did this, we would first see that the networks of existences that allow different social groups to survive and reproduce would look very heterogeneous. But what would also be clear is how some social groups would share means of reproduction with some more than others—similarities and dissimilarities that would allow us to reclassify social groups on the basis of material conditions of existence. Perhaps this would even allow us to redefine exploitation as the surplus of existence that some social groups profit from, by describing how the livelihoods of some collectives prevents the access to a habitable territory for others. I think that the Yellow Vests in France perhaps showed us the urgency of the geosocial question. Would you agree?

BL: I think the Yellow Vest affairs started with an interesting moment of geosocial inquiry, as it was a matter of salary, taxation, gas, landscape, and social justice. So you are right; initially, the connection was made. But you cannot have a political position if you cannot describe your own territory. So nothing came out of it precisely because they did not have the vocabulary, tools, or political movement to help them articulate this link. We are extraordinarily bad at describing what allows people to subsist. We talk a lot about identity, we have a lot of discussions about values, but please describe to me the territory in which you survive, in which you invest, and might want to defend. I think the lack of such descriptions is what renders the political scene so interesting but also so violent today. We begin to realize that this is the real question, but we do not know how to answer it. This is also why I am interested in the episode of the Cahiers de Doleances, because it was exactly an initiative directed towards territorial descriptions and questions of social justice in one and same breath. The Yellow Vests did not manage to maintain this link.

So if the question of geosocial classes is difficult to answer, it is because we all have very little idea about where we get our subsistence from. We have simply lost the habit of describing what we are attached to, what we are connected to, and what allows us to survive. In a way, Marxism used to be a vocabulary that allowed such descriptions of our conditions of subsistence, which we could use to locate ourselves inside the system of production. Can we do the same thing today with what I call the processes of engendering? From Proudhon to Marx, socialism described the practical and material realities of industrial society. They described where people within this society got their subsistence from, which allowed people to position themselves in the system of production. But today, we live in a different world. Today, if one would have to describe the practical, material world in which one lives it would not only be about industry, we would furthermore have to add entities like the climate, carbon dioxide, water, bugs, earth worms, soil, and others—the wider array of material conditions of existences that you spoke about before. And this is what ecologists never managed to bring to the attention of socialists. It is still the question of inequality, of justice, and of the material world out of which we get our subsistence; it is simply that the world has changed form.

NS: Yes. The interesting thing is that in the first period of the Yellow Vests, when there was a moment of geosocial description, they actually enjoyed support and were able to mobilize affects internally and externally. When they lost their territorial descriptions, it turned violent. It seems that in some situations, violence does not occur when indignation reaches a certain level; it occurs when you are no longer able to describe who you are, what you are attached to, and with whom you fight.

BL: Yes, they lost completely their territorial descriptions, and instead went on to ask for the head of the president. . . . Macron then offered them a grand debate, but we learned nothing from it because people simply gave their opinions. But the opinions of people who have no land nor a world to describe is useless. A million and a half answers to the debate and not one single description of where we reside and with whom. Values? Yes. Identity? Yes. But no territories. If you have lost the ability of describing the land or the territory on which you reside—understood in the etiological sense as the lists of entities you rely on to subsists—then you simply cannot do politics. If you have no territory, you have no politics.

NS: So to restart politics, we need to redescribe our territories, our lands, and our people. How come we lost the ability of doing so? Were we atomized by neoliberalism, which is fundamentally an ideology and politics of disattachments?

BL: Of course, this is one of the reasons. But you can simply also just loose the habit and culture of doing politics, if it is not constantly maintained. Redescription is a general rule of the social sciences, but today I would say that this is the political question. Let us not forget that ecological mutations are unprecedented. We have never before had a moment where we had to reengineer the whole system of reproduction piece by piece, house by house, mobility by mobility, food by food. We have the experience of production and modernization, but we do not have any experience of reproduction and remodernization. Eight billion people and every single material entity that binds their societies together and make them live are controversial. Meat is controversial, clothes are controversial, transport is controversial. In this situation, we cannot skip the phase of description of territory, unless you want to end up in an abstract world of identity or values. This is what happened in England. If we do not do the work of description, we cannot go forward.

NS: This leads me to my next question. Forty years ago, you started your career by following natural scientists in the laboratory. Now, you are interested in a new sort of science and a new sort of scientist. In Down to Earth you dedicate a chapter to critical zone’ and critical-zone scientists, and you are currently doing an exhibition on the topic. Why are you interested in these topics and how are they related to the task of description?

BL: First, critical zones and critical-zone scientists are words used in geoscience, hydrology, geomorphology, geochemistry, and in soil sciences to denote the thin crust or skin of the Earth and the scientists that are studying it. And, yes, when I have been following and studying these scientists for five years now, it is exactly because I think they help with the redescription of territories in a very practical way. First, because they are not global. They are not working with the Earth as the globe. Rather, it is the Earth as a thin skin. Everything on which life forms live exists only here, on a few kilometers thick pellicule of the earth, reaching from the atmosphere and a few kilometers down in the rocks. So, what they study is comparable to Lovelock’s discoveries. It is another tool to get away from the idea of nature, which is simply too big, abstract, and imprecise. When you study critical zones, you study a series of things or connections on the crust of the Earth, so it has a modest reach. It is about very limited entities; it is not the whole cosmos. The second interesting thing about these sciences is that they explicitly study the differences between what they see in the laboratory and what they see in the field. Again, there is this modesty, it is a boots-on-the-ground type of science—a bit like natural history or like Alexander von Humboldt’s natural science.

NS: It is another epistemology.

BL: Yes. Epistemologically, they are far from the other sciences that I have been following for many years. And since they underline the discrepancies between their observations and the chemical reactions, it means that they are redescribing and rematerializing the question of territory, which we simultaneously try to redescribe and rematerialize in political and social theory. This is also where there is a link between Lovelock’s discovery, the political question of geosocial classes and critical zones. This is why I am interested in them and why I am also doing an exhibition on the topic.

NS: Why an exhibition? What are the role of the artists in it?

BL: Exhibitions allow you to do a thought experiment in a limited space that cannot be done in any other way. Every time I have done an exhibition, the question at hand was completely impossible to raise in a book but possible to raise in a space. Why? Because you are able to submit people to an experiment. This is what I mean by thought exhibitions. It is a way to use limited space, art, and artists to bombard visitors with expressions and then see what happens with them. The last one I did in 2016 Reset Modernity,[13] bombarded visitors with objects, asking if they could reset their vision of modernity.[14] The current exhibition—simply called Critical Zones: Landing on Earth—is somehow easier. It basically offers a lot of scientific facts and arts from which the visitors can learn to redescribe and revisualize the Earth’s surface in which they live but which they are not conscious about, in large part because of the cartographic imaginary we spoke about before. The problem remains the same. We always think of the Earth, seen from the outside. If you say “Earth,” what typicaly comes to peoples’ mind is the globe. But despite all the talk about the Blue Planet, only the people who are out of space, out in space, experience the Earth like that. We are not out in space; we are inside critical zones. And this is what we need to visualize. Here, the importance of artists is that they help us multiply the visions of the Earth, viewed from the inside and not from the outside. It sounds simple, but it is absolutely crucial not to imagine the planet as the globe if we want to land on Earth. The globe is too big and too abstract. So, what we simply try to do is to invent with scientists and artists a vocabulary for this landing. In a way, it is surprising that we even have to do so. Why should we have to land? Are we not on Earth? In a way no, because Moderns took off on an interesting and somehow beautiful journey, as visualized by Musk and his Tesla, but now we realize that we have to land again without crashing. As I say in Facing Gaia (2017), we are exactly in the same position as when we “discovered” the New World and when the cartographers had to redraw their maps. Four centuries later, we discover a new, moving earth. Not in extensity but in intensity, an earth which is reacting to our actions. For that you need new descriptions, and you need new visualizations.

Notes

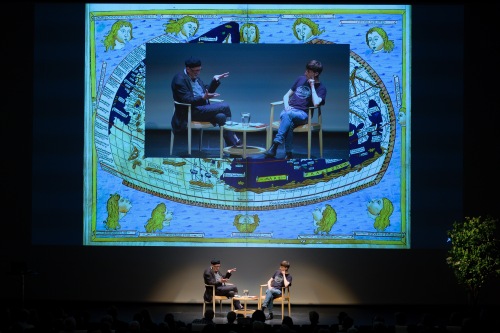

This conversation between Bruno Latour and Nikolaj Schultz took place at The Queens Hall, Royal Danish Library on 29 May 2019. It has since been edited and substantially revised. Selections of the conversation were first published as an audio file by the Danish newspaper Dagbladet Information for their podcast series “European Ideas.”

Nikolaj Schultz, sociologist, is a PhD Fellow at the Department of Sociology, University of Copenhagen. He is currently a visiting scholar in Paris, where he is working with cosupervisor of his PhD thesis, Bruno Latour, on developing the concept of geosocial classes. Bruno Latour, sociologist and philosopher, is Professor Emeritus at Sciences Po, Paris. He is currently preparing the Critical Zones. Observatories for Earthly Politics exhibition, cocurated with Martin Guinard, Peter Weibel, and Bettina Korintenberg, set to open 8 May 2020 at the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe.

[1] See Bruno Latour, Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime (London, 2017).

[2] See Michel Serres, The Natural Contract (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1995), p. 86.

[3] See Alexandre Koyré, From the Closed Cosmos to the Infinite Universe (Baltimore, 1957).

[4] See Latour, Down To Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime (London, 2017).

[5] See Pierre Charbonnier,. Abondance et liberté. De la revolution industrielle au changement climatique (Habilitation thesis, L’École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, 2019).

[6] See Johann Gottlieb Fichte, The Closed Commercial State, trans. Anthony Curtis Adler (New York, 2012).

[7] See Nikolaj Schultz, “Life as Exodus,” in Critical Zones: Observatories for Earthly Politics, ed. Latour (forthcoming).

[8] See Evan Osnos, “Doomsday Prep for the Super-Rich,” New Yorker, 22 Jan. 2017, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/01/30/doomsday-prep-for-the-super-rich

[9] See Julie Turkewitz, “A Boom Time for the Bunker Business and Doomsday Capitalists,” The New York Times, 13 Aug. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/08/13/us/apocalypse-doomsday-capitalists.html?searchResultPosition=9

[10] See Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, N.C., 2016).

[11] See Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston, 2001).

[12] See Schultz, “Geo-Social Classes: Stratifications in the System of Engendering,” in Critical Zones.

[13] See Latour, Reset Modernity (Cambridge, Mass., 2016).

[14] See Latour, Reset Modernity.

Pingback: The Climatic Virus in an Age of Paralysis | In the Moment

Pingback: The Resolution Will Not Be Televised – Ibrahim Lawson