Read the Books That Schools Want to Ban

These 14 titles have been under attack for doing exactly what literature is supposed to do.

Updated at 13:58 p.m. ET on February 3, 2022.

Book banning is back. Texas State Representative Matt Krause recently put more than 800 books on a watch list, many of them dealing with race and LGBTQ issues. Then an Oklahoma state senator filed a bill to ban books that address “sexual perversion,” among other things, from school libraries. The school board of McMinn County, Tennessee, just banned Maus, Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize–winning graphic memoir about the Holocaust. Officials said that they didn’t object to teaching about genocide, but that the book’s profanity, nudity, violence, and depiction of suicide made it “too adult-oriented for use in our schools.”

No one has yet figured out how to depict the Holocaust without ugliness, for the very obvious reason that it was one of the greatest crimes in human history. Maus details the cruelties that Spiegelman’s father witnessed during World War II, including in Auschwitz, as well as the pair’s complicated relationship after the war. Some nudity shows Jews—depicted in the book as mice (their German oppressors are drawn as cats)—stripped naked before their murder. Hiding these images from children purposefully ignores the mechanized gruesomeness of the Holocaust. And Maus’s removal isn’t a side effect of an otherwise neutral attempt to keep classrooms wholesome. As I wrote in December, getting rid of books that spotlight bigotry is the goal.

Books have been the targets of bans in America for more than a century. Maus is not the first, or the last, casualty of an ideology that, in the name of protecting children, leaves them ignorant of the world as it often is. The following 14 books employ difficult, sometimes upsetting imagery to tell complicated stories. That approach has made them some of the most frequently challenged, or outright banned, books in America’s schools; it also makes them perfect examples of what literature is supposed to do. Please consider buying them for the students in your life, and for yourselves.

To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee

Lee’s 1960 novel about a white lawyer defending a Black man falsely accused of rape in a segregated Alabama town won the Pulitzer Prize and was adapted into an Oscar-winning film. The novel, long used in classrooms as a parable about American racism, has faced various controversies over the decades. Last week, it was removed from a Washington State school district’s required-reading list—although not outright banned—for its racial slurs and for the perception of Atticus Finch as a white savior.

The Handmaid’s Tale, by Margaret Atwood

Atwood’s popular dystopian story turns the United States into a Christian theocracy called Gilead, where fertile women are stripped of their name and impregnated against their will. Its sexual violence and criticism of religion have made it ripe for challenges in schools. The original book, its adaptation into a graphic novel, and its sequel, The Testaments, were pulled from circulation, then quickly restored, in a Kansas school district in November.

The Bluest Eye, by Toni Morrison

Morrison’s first novel, The Bluest Eye, has shown up multiple times on the American Library Association’s annual list of challenged books. The classic, which kicked off Morrison’s Nobel Prize–winning career, follows Pecola Breedlove, a Black girl with a tragic family history and a deep desire to have blue eyes. In January, The Bluest Eye was removed from a Missouri school district’s libraries to keep children away from painful scenes of sexual abuse and incest—which in Morrison’s hands become illustrations of the insidious psychological damage that racism deals to her characters.

Fallen Angels, by Walter Dean Myers

This Coretta Scott King Award winner, like many of Myers’s novels, follows a young Black protagonist. In this story, 17-year-old Richie Perry leaves Harlem for Vietnam, where he faces the horror and banality of war. As with Myers’s 1999 book Monster, some have deemed it too violent and profane for students.

Heather Has Two Mommies, by Lesléa Newman

Newman’s 1989 picture book broke ground by depicting exactly what its title says. A young girl named Heather has two lesbian mothers and realizes in the story that her family is different from her schoolmates’ families. She learns why she doesn’t have a father, and that there are many different kinds of families. Newman’s story might feel anodyne today, but the furor it caused in the 1990s, when it was the ninth-most-challenged book of the decade, hasn’t abated: Heather was taken off the shelves in a Pennsylvania school district in December.

Maus, by Art Spiegelman

The truth of the Holocaust is both abstracted and explicitly rendered in the graphic memoir Maus, which was banned in a Tennessee county last month by a unanimous vote. Spiegelman draws his Jewish family and protagonists as mice, Germans as cats, and Poles as pigs, but this style doesn’t fully blunt the hideousness of the victims’ suffering. Some of the topics that got the book banned, such as Spiegelman’s mother’s suicide, are essential to rendering the effects of the war. Without them, it would be a different story entirely.

Speak, by Laurie Halse Anderson

This 1999 young-adult book about a teenager dealing with the effects of sexual assault was notably called “soft pornography” in a newspaper op-ed that drew notice from Anderson herself. Speak’s honesty about its protagonist’s trauma and the subsequent social shunning she endures has made it a perennial classic—and a target for criticism.

His Dark Materials, by Philip Pullman

Pullman’s award-winning fantasy trilogy is populated with talking armored polar bears, soul-sucking specters, and translucent angels. But ultimately, it’s about a war on adolescence. The story’s villains, all affiliated with an allegorical version of the Catholic Church, are motivated by a perverse desire to keep children innocent—even by essentially lobotomizing them. In contrast, the heroes celebrate knowledge and fight to overthrow the religious hierarchy threatening their world. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the books were criticized for their supposed anti-Christian themes and plotlines involving witchcraft.

Looking for Alaska, by John Green

The teenagers at Green’s Alabama boarding school drink, smoke, swear, and fumble their way through life. Those actions have made the novel controversial for more than a decade. Green, whose later book The Fault in Our Stars was hugely popular, has repeatedly defended it—including what he calls its intentionally “massively unerotic” oral-sex scene.

Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates

This epistolary book by the famed Atlantic writer reflects on racism’s long shadow. Coates’s frank assessment of the effect of centuries of racial violence on contemporary Black Americans has been attacked in some schools. Between the World and Me and Coates’s We Were Eight Years in Power are also included on Representative Krause’s list of books that “might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex.”

The Hate U Give, by Angie Thomas

Thomas’s debut young-adult novel was a best seller and was quickly adapted into a film. Starr, a Black teenager, witnesses a white police officer kill her friend at a traffic stop. While navigating her grief, she gradually becomes a public advocate for racial justice. The Hate U Give has been challenged for its profanity and depiction of drug dealing, but most vigorously for its thematic connection to the Black Lives Matter movement. A South Carolina police union objected to its inclusion on a high-school reading list, calling it “almost an indoctrination of distrust of police.”

Gender Queer, by Maia Kobabe

Through illustrations and tender writing, this graphic memoir follows the nonbinary author’s journey of self-discovery. Its exploration of sexuality and gender, especially in illustrations depicting oral sex, made its inclusion in school libraries a prime target for criticism last year.

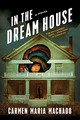

In the Dream House, by Carmen Maria Machado

Machado’s captivating, experimental memoir details her abusive relationship with another woman, and her eventual escape from it. At a March 2021 school-board meeting in Leander, Texas, a parent read a sex scene from the book aloud and held up a pink dildo as part of an effort to demand its removal from a book club. In December, the district removed the book permanently from Leander schools.

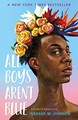

All Boys Aren’t Blue, by George M. Johnson

The essays in this collection take apart and examine Black masculinity, queer sexuality, and Johnson’s own life. The book has been removed from school libraries in multiple states and lambasted as “sexually explicit,” which the author called “disingenuous for multiple reasons.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.