In March 2020, just weeks after the novel coronavirus upended routines and forced schools to shift to remote learning, California mom Melissa* was already planning for extended closures. “I saw the writing on the wall,” she says. Online school had been a disaster for her daughter, then 4-and-a-half years old. “She lasted about two weeks online and then didn’t want to have anything to do with it,” Melissa says.

With the prospect of virtual kindergarten looming, Melissa set a new plan in motion: She withdrew her daughter from school and prepared to establish a microschool in the family’s backyard. By September, Melissa had reconfigured the space with new furniture, hired a teacher and recruited five other kindergarten families.

Last summer, as schools wavered in their reopening plans, some parents turned to microschools — also called pandemic learning pods or pandemic homeschooling pods — as a solution. In July, a San Francisco parent started the “Pandemic Pods” Facebook group. It now has almost 40,000 members and a website with resources to guide families. By offering a learning environment outside of a traditional school building, pods aim to provide structure, stability and socialization within a smaller cohort of students to reduce COVID-19 exposure risk.

In pods like Melissa’s, families share the cost of a teacher, tutor or pod facilitator; in others, parents volunteer to work with the kids. Some pods provide their own curriculum and materials, while others support students who remain enrolled in their school’s remote learning programs. The decision to form a pod raises complex equity and social justice issues: Pods are less likely to focus on diversity and can siphon resources away from public schools if families opt out of the system.

More than three million students nationwide participated in pods in 2020, according to an Education Next parent survey. For some families, pods were a godsend, spaces where children flourished and adults shared the workload amicably. But other pods were fraught with interpersonal challenges, from minor frustrations — what one parent calls “periods of uncomfortableness” — to communications breakdowns, mean-girl dynamics and fundamental disagreements about what was safe and what was too risky.

There’s No Playbook for Running a Homeschool Pod

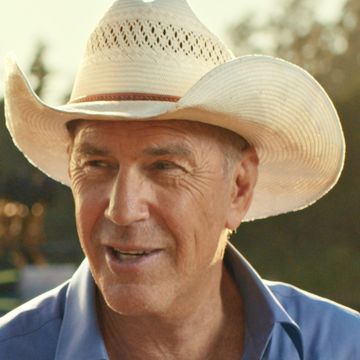

In a regular school, administrators create the policies, but in a pandemic pod this responsibility falls entirely on parents. “You’re all of a sudden the administration,” says Michael Horn, author Disrupting Class: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns and education writer and speaker.

This fall, Horn started a microschool at his home in Lexington, Massachusetts with his two elementary school-aged daughters and children from three other families. He says parents often underestimate how much time it takes to set up a pod. There’s no playbook you can pull from, because school policies aren’t designed for a group of four or five learners.

Pod parents need to decide where to locate the learning space, for example, along with how much families will contribute financially and how to handle things like sick days and discipline. In a pod there is no teacher or administrator to mediate conflicts, says Horn, and you can’t just get together with the other parents for a drink and complain about the school leaders being out of touch. And in the age of COVID-19, determining a pod’s health policy can be particularly arduous.

“A parent in a family has the sniffles, but the kid doesn’t,” Horn says. Parents have to decide: Can the pod still meet that day? Should the child attend or stay home? “There are a lot of uncomfortable conversations to be had,” he says, as parents try to mesh their different definitions of what’s safe.

Over the summer, Wendy*, a mom in Utah who has a teaching background, decided to pause her career plans so she could lead a homeschooling pod for seven children, including her own. The other parents in the pod were Wendy’s relatives, which was tricky because “things can get personal really fast,” she says.

Still, Wendy was optimistic. With her experience, she says, “I was a good fit to run a pod, so to speak.” She drew up a detailed contract outlining COVID-19 protocols and specifying how much she would be paid as the teacher.

One of the parents disagreed with some of the contract’s terms and refused to sign it. As the school year began, Wendy didn’t want to lose learning time, so “eventually we started without a contract,” she says. But this decision took a toll on Wendy’s mental health. The pod felt “unstable from the very beginning.”

Communication Poses Challenges

Once a pod is up and running, you can’t simply “set it and forget it, which is often how we treat school,” says Horn. “The first thing that I saw a lot of parents underestimate was the importance of communication on a really regular basis.”

Julie Burwell, a Chicago-area freelance copywriter who runs a pod for her fourth grader and two classmates, agrees. Initially, she assumed the e-learning aspect would be a “nightmare,” but the hardest part has actually been ensuring the parents work well together and communicate regularly. “It is its own job right now for me,” she says.

All of the pod parents check in frequently and whenever something changes, from local public health requirements to personal circumstances like travel and vaccinations. These are conversations that, Burwell says, “if they’re not handled well, they feel really judgmental or really condemning” because they involve personal choices and behavior. “It’s a lot like dating,” she adds, in the questions you have to ask: Are you seeing other people? Do you mean casually? Are you going inside their homes? If so, is everyone wearing masks? This extreme openness is awkward at times, but it works: The families in Burwell’s pod recently decided to stick together for the rest of the school year.

If parents aren’t committed to transparency, problems can pop up quickly. In North Carolina, Aimee’s* first grader has been part of a pod with three other families. To minimize infection risk, all of the parents agreed upfront that any children’s birthday celebrations would be held exclusively with their podmates. But later in the year, Aimee was scrolling Instagram and saw that one of the families had hosted a separate, out-of-pod birthday party. “That just felt frustrating because they didn’t communicate about it,” Aimee says.

Danielle*, a mom in California, was similarly blindsided. When she learned her child’s public elementary school was unlikely to resume in-person instruction, Danielle began looking for potential podmates. “I interviewed over 150 families to get four that were mostly a fit,” she says, and started the school year off with a pod.

A couple months later, the school announced it would offer an in-person option after all. Danielle’s impression was that all of the families would continue with remote learning, but suddenly one of the children stopped coming to the pod. Danielle later learned from the school that the missing student was enrolled there in-person. “I made an angry phone call, which I shouldn’t have done,” says Danielle. “And that’s when we found out that they were leaving the pod.”

In some pods, communication broke down to the point that it resembled high school “mean girl” behavior. Early on, Melissa noticed that one of the families in her pod was violating agreed-upon protocols, which included disclosing any travels and quarantining for a week upon return. Both the mom and the dad in that family were traveling separately without telling anyone, flouting the rules.

When confronted, not only did the mom disparage Melissa’s concerns, “she was also kind of turning into like a ringleader,” getting two other moms in the pod to back her up, Melissa says. “They were trying to sort of defend this one mom’s activities by saying either that I was overreacting or that they didn’t need to report everything to me, and that there should be a level of trust.”

Then the situation worsened. The mom’s texts to Melissa became increasingly uncivil, she says, and “nasty, in a personal way.” Finally in December, Melissa asked the family to leave the pod, which was “horrible,” she says. “But it was necessary for me to keep my sanity and for me to be able to function, because I was just losing sleep over it.”

All of the Benefits Without the Work

Joining a pod can involve multiple expenses, from refurbishing space in a home for learning and stocking it with supplies to paying lawyers to create contracts. Hiring a teacher is a big investment, too: In some microschools, the cost can be upwards of $20,000 per family for the entire school year. But pods aren’t costly just in terms of dollars — they also require a huge time commitment from parents. And some families, especially those hosting pods in their homes, found themselves with the heaviest workloads.

“Most of the parents volunteering disproportionately” are not full-time educators, says Horn. This quickly becomes exhausting “in a way that I think a lot of those parents perhaps weren’t prepared for.”

In Aimee’s pod of four families, the school year started with her family and another rotating hosting duties each week. One of the remaining families couldn’t host due to medical risk factors, which Aimee understood. But the fourth family had a different reason: Their home was undergoing renovations.

“We just kind of left that alone,” says Aimee, assuming the family would join the rotation when the project was finished. But as the second semester began, nothing had changed. When Aimee tried to revisit the conversation, the parents responded that they still couldn’t host because they both worked full-time and didn’t have offices.

Aimee was stunned. All of the parents in the pod work full-time — why couldn’t this family be part of the rotation too? “They’re pretty content to keep not hosting,” she says. “It feels frustrating because like, we are all working, you know?”

By contrast, Theresa Dowell Blackinton, a writer and editor in Durham, North Carolina, is grateful that her two-family pod decided to share hosting duties equally. Her pod includes four children: two pre-kindergarteners and two first graders. Blackinton is responsible for the younger kids on Monday and Tuesday and hosts the older kids on Thursday and Friday, while the other mom has the opposite schedule.

“I think part of why it works so well for us is the kids get a change of scenery,” she says. Plus, the adults get a break one afternoon every week, when each mom hosts the entire group.

While Melissa always planned to be the permanent host for her pod, she sometimes feels taken advantage of by the other parents. As a single mom, Melissa manages the microschool on a volunteer basis while also working full-time and caring for her daughter. When the pod shut down for a week around the holidays so families could obtain COVID-19 tests after traveling, several parents asked Melissa if she was providing online activities for the kids. “We paid for that week, and what do you expect us to do?” she recalls them asking.

After Melissa asked one family to leave the pod, she needed to find another family to fill the vacancy – and pay the $20,000 in tuition now missing from the teacher’s salary. She asked the other parents if they could help recruit a new student. Even though the other families liked the teacher and wanted to retain her, no one lifted a finger to help. Melissa was beyond exasperated. “They want all the benefits,” she says, “but they sure do like to complain.”

The Pandemic Wild Card

Even in the most well thought-out learning pods where the workload was balanced and communication was effective, the pandemic and its associated risks were a wild card that proved difficult to overcome.

“We had what I thought was a great pod,” says Jill*, a mom in Massachusetts who teamed up with two families to provide instruction for her child and two other pre-kindergarten learners. For the first few months, everything worked well. But in January, Jill discovered that the nanny in one of the families had a boyfriend — adding a dimension of risk that made Jill uneasy.

Jill’s family decided to leave the pod. Though it was the right choice, she feels sad about what happened and worries her decision hurt the other families. “We built such trust and such friendship,” she says. “Now I feel like I let them down.”

For Horn’s pod, fall was “a magical three months,” he says. The children were able to meet outdoors in his family’s backyard, minimizing COVID-19 risks. But as the weather cooled, a new safety concern emerged: The teacher’s home situation changed, increasing exposure risk for the whole pod. Horn tried to address everyone’s needs, finding a new instructor and space to conduct class inside. But the other families wanted to keep working with the original teacher — and Horn’s family wasn’t comfortable moving indoors in that scenario. At that point, his family decided, “Okay, we’re out.”

Horn’s experience reflects how difficult it can be to keep a pod going, especially in the midst of a novel virus that’s constantly changing — and with it, our understanding of what “safe” really means. Families have different priorities, and the moment a pod isn’t serving them all equally, “all of a sudden you’re not in lockstep anymore,” he says. “That’s when you see a lot of break-ups.”

Wendy’s pod, which had started on shaky ground, faced a setback in November: One of her adult relatives in the pod contracted COVID-19. After weeks of quarantine and uncertainty about how to safely resume instruction, Wendy felt drained. She considered reworking the contract and starting again, but given that one parent never signed the original document, Wendy decided it was time to step away. She didn’t feel her concerns as a teacher were being taken seriously — a sentiment she says other educators have shared during the pandemic.

After the pod disbanded, Wendy found herself back at the kitchen table, working with her own kids. “People in my family literally cried when it ended,” she says. It was a “funny kind of grief.” Wendy has no plans to start another pod, but she hopes everyone can move past what happened and focus on being a family again.

Despite the mishaps and stress, most parents in this story say they would participate in a pod again, albeit with some changes. In particular, Horn would approach two aspects differently. He would establish stronger boundaries about what everyone in the pod was committing to in terms of safety expectations. And he would invest a lot more time in finding the right teacher, a decision he says was rushed.

In the face of an unprecedented pandemic that offered few lifelines for families, pods were far from a faultless solution — they were just one choice in a menu of imperfect education options for this past school year. Still, pods offered the structure, consistency and sense of community that kids and parents desperately needed. Although the hosting situation was frustrating, Aimee says being part of a pod was “extremely sanity-saving.” She can’t imagine how her first grader would be functioning without it.

“It instills some sense of routine and normalcy to life, when it’s very, very abnormal,” agrees Blackinton.

While Melissa never found another family to replace the one that left, she ended up hiring a new teacher who was happy with the lower salary and turned out to be a much better fit personality-wise. Communication has improved, and the children are thriving — both academically and socially. Without the pod, Melissa says, she wouldn’t have been able to give her daughter this experience, let alone manage her own job and day-to-day responsibilities.

Even after all the challenges, “I wouldn’t change a thing,” she says. “The laughter and the joy is just what makes it all worth it.”

*Names have been changed