George Soros and the Demonization of Philanthropy

Conspiracy theories about him obscure the real concerns about how large-scale giving works today.

George Soros is an exceptionally busy man, at least according to right-wing conspiracy theorists. Just within the last year, he has been credited with single-handedly funding the Black Lives Matter and antifa movements, as well as with bankrolling (as a false-flag operation) the white-nationalist rally in Charlottesville against which both of those groups mobilized. Soros has been accused of masterminding Colin Kaepernick’s NFL protest and the Women’s March, and with pulling the strings that led H. R. McMaster, President Donald Trump’s national-security adviser, to fire alt-right–aligned staffers. And last week, the supporters of the Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore alleged that Soros paid women to falsely accuse him of sexual assault.

Soros, of course, has been the subject of intense scrutiny for decades. Ever since he made $1 billion by shorting the British pound in 1992, the power Soros wields over financial markets has loomed large in the public imagination. By the early 2000s, when Soros had become one of the top funders of the Democratic Party—he once declared that he’d willingly trade his entire fortune to prevent President George W. Bush’s reelection, though in the end he only spent $27 million, an unprecedented sum at the time—he also became a partisan target for conservatives.

But it hasn’t been Soros’s financial buccaneering or even his political giving that have featured most prominently in the conspiracies about him. It’s been his philanthropy. Soros has long been one of the leading donors to progressive causes in the United States and is the most generous financial supporter of pro-democracy organizations around the world. And his giving will likely only increase in the years to come. In October, Soros disclosed that over the past few years, he has turned over about $18 billion to the institution through which he has channeled his philanthropy, the Open Society Foundations (OSF). The enormous gift was met as a confirmation of all the darkest fears stoked by his antagonists. Pointing out that Soros’s foundation would now rank as the second largest behind the Gates Foundation, the right-wing website Breitbart announced the news by referring to OSF as the “Death Star.”

Stories of Soros as philanthropic bogeyman are clearly symptomatic of the current political moment. The vastness and the viciousness of the partisan divide, coupled with the general suspicion of financial “elites,” can make it tempting to focus ideological frustrations on a few munificent individuals who belong to the opposing political team. If conservatives do so with Soros, progressives have their own set of donors whom they demonize—such as the Koch brothers, and more recently, Robert Mercer—though, in general, progressive conspiracies involving conservative benefactors tend to be more closely tethered to reality.

What’s less well understood is how narratives that pit scheming benefactors against “the people” can work against the values of a democracy. Not only are conspiracy theories often deliberately employed by authoritarians to undermine grassroots activism, but they also muddle discussions about the immense power philanthropists actually do wield, crowding out valid concerns about the role mega-donors now play in shaping society.

The philanthropist has always been a figure fit for abuse—the term was coined by an ancient Greek dramatist to describe Prometheus, whom the gods tortured for the crime of bringing fire to mankind. Early-modern uses of the word philanthropy referred not to large-scale giving but rather to promoting a set of egalitarian, universal values. As the term became used more widely during the Enlightenment, it became associated with ambitious reformist causes such as abolition. It also absorbed many of the critiques directed at such movements: These philanthropists, critics claimed, spoke in grand terms about the rights of Man but ignored the poor and oppressed in their own communities. The grandiose universal values they promoted threatened to loosen religious and geographical bonds. After the French and Haitian revolutions, whose champions claimed to be marching under philanthropy’s banner and pursued violent means to achieve emancipatory ends, the concept began to carry the whiff of menacing radicalism.

Then, in the late 19th century, the meaning of philanthropy began to change. With the rise of industrial fortunes and the large-scale monetary contributions derived from them, the word came to signify large-scale giving. (That idea may seem unrelated to the word’s roots, but the conceptual link is that both bold social reforms and modern philanthropic foundations are premised on the inadequacy of modest, intimate, small-scale charitable donations to address the world’s most pressing problems.) Industrial titans—John D. Rockefeller, to name one—funneled their wealth into ambitious programs of institution-building, research, and reform, and in the process attracted to philanthropy the antagonism provoked by the rise of global capitalism.

The United States (and its economy) has been highly hospitable to philanthropists, but it has also provided a political system that nurtures conspiracy theories directed against them. Historically, both the right and left have crafted their own narratives, each fueled by a deep suspicion of concentrated power. Early-20th-century progressives worried that robber-baron benefactors were creating a shadow state that would overwhelm the federal government; conservatives and populists warned of the dense networks of charities, academic institutions, and private foundations that controlled public opinion. By mid-century, right-wing anti-Communist conspiracies targeted major philanthropies as seedbeds of pernicious internationalism. In the 1950s, congressional investigation of philanthropy sought to determine whether foundations subsidized “un-American and subversive activities” and supported efforts “to undermine our American way of life.” In the following decades, anti-imperial and anti-globalization movements lodged both legitimate grievances about philanthropies and more decadent tales of their power.

George Soros might as well have been focus-grouped to attract the various antipathies that have long swirled around philanthropy. He’s a champion of globalism, capitalism, and progressivism. He’s also Jewish, and anti-Semitism has long grown up alongside the major critiques of those forces. As anti-Semitic lore has it, the humanitarianism of the “International Jew” is merely a cover for an interest in global domination. Soros’s Jewish identity is rarely explicitly invoked by his antagonists, but it doesn’t need to be: Every invocation of his “cosmopolitanism” and his essential foreignness serves as a dog whistle for those who savor the lineage of those slurs.

Soros’s Open Society Foundations have together given away some $14 billion over the last three decades—mostly to social-justice, pro-democracy, and human-rights causes—and now operate in more than 100 countries around the world. His first major gift, made in 1979, funded scholarships for black South Africans. In 1984, he established a foundation in Hungary to cultivate the shoots of liberalism growing beneath Communist frost; his philanthropy provided copying machines, for instance, that allowed anti-Communist activists to print samizdat literature. After Communism’s collapse, Soros-funded foundations nurtured nascent pro-democracy institutions in nations throughout Central and Eastern Europe, paying for travel grants for students, supporting watchdog organizations that promoted good governance and human rights, and seeking to protect vulnerable and marginalized populations such as the Roma. In 1991, he founded the Central European University in Budapest to promote open academic inquiry. Most recently, Soros has supported a liberal immigration policy in Europe as a response to the refugee crisis.

Soros has never shied away from controversial issues, and his philanthropy has long generated controversy. But his transformation into a figure of almost demonic power is a more recent phenomenon. It’s the product of two trends, one domestic and the other international.

In the United States, conspiracies about Soros were first spun by leftists opposed to globalization. But those narratives soon found a home on the other end of the political spectrum. Right-wing media provocateurs seized on Soros’s globalism as exemplifying the beliefs of a small group of “radical infiltrators” who were “quietly transforming America’s social, cultural, and political institutions,” in the words of one popular 2006 polemic called The Shadow Party. On Fox News, Glenn Beck devoted entire episodes of his show to sketching out the twisted “One World Government” ambitions of the man he refers to as the “Puppet Master.”

Internationally, the demonization of Soros has coincided with what two decades ago Fareed Zakaria marked as the rise of illiberal democracy—regimes that are democratically elected but that ignore the “constitutional limits of their power and depriv[e] their citizens of basic rights and freedom.” After the “color revolutions” in Ukraine and Georgia in 2003 and 2004, in which several Soros-funded NGOs were involved, Vladimir Putin exploited these discontents to suggest that the uprisings had been orchestrated by Soros. The global financial crisis created a climate especially ripe for sowing suspicions about the machinations of a global financial elite. Other authoritarian leaders around the world took up the charge, suggesting that political agitation and grassroots mobilization against their rule was not in fact an expression of popular will but manufactured by shadowy outside forces, over which Soros presided.

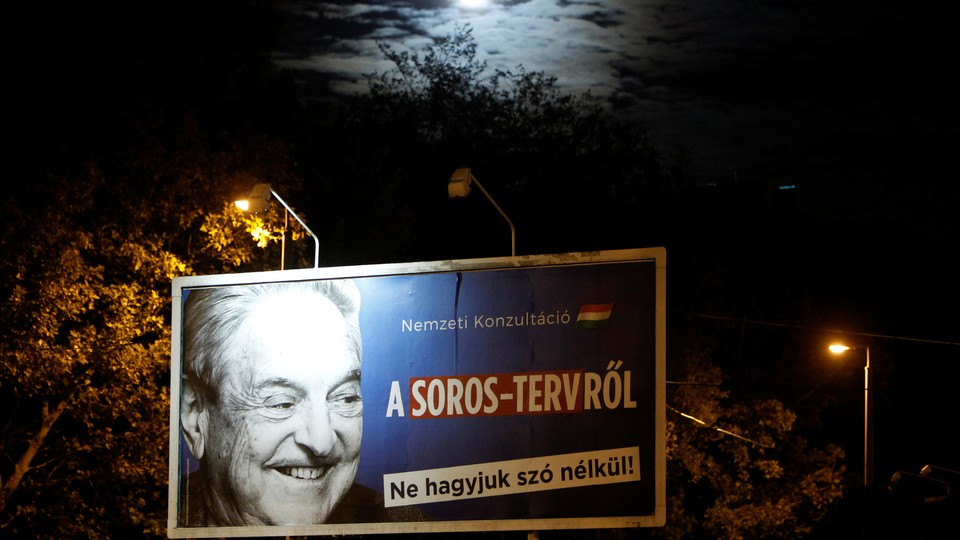

This dynamic has recently been on display in the country of Soros’s birth, Hungary, where the ruling party of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán (who, in his youth, benefited from a Soros-funded fellowship to study at Oxford), recently spent $21 million on billboard ads against liberalizing immigration policies, some featuring a menacing photo of the philanthropist and the caption Don’t Let George Soros Have the Last Laugh. (Unsurprisingly, the posters soon attracted anti-Semitic graffiti.) Orbán’s party has also passed legislation clearly meant to shut down Central European University, which Soros founded (thousands protested in response). And in October, Orbán announced a “national consultation” in which a government-funded questionnaire was circulated to citizens to survey their views on an imagined master plan hashed by Soros and European Commission leaders to abolish refugee quotas. Orbán has also directed the nation’s spy agencies to investigate a “Soros empire” of organizations that he claims seek to undermine Hungary’s Christian culture.

Right-wing leaders in nearby countries have also hyped Soros conspiracies to rally their base. In Macedonia, the former prime minister has called for the “de-Sorosization” of society. In Romania, the head of the governing party blamed anti-corruption protests on Soros and claimed that he “financed evil.” These campaigns—along with similar ones in Serbia, Slovakia, and Bulgaria—aim not just to tar the progressive policies with which Soros is now closely identified (specifically, more open immigration), but to undermine pro-democracy organizations that could challenge their political power.

With Trump’s election and the ascendance of American right-wing nationalism, these domestic and international strands have converged. In March, a group of GOP senators asked Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to investigate the extent to which U.S. funds were being given to OSF, allowing it to “impress left-leaning policies on sovereign nations, regardless of their desire for self-determination.” (The State Department declined to look into it). And last week, on Twitter, Trump’s close congressional ally, Representative Steve King, linked to an anti-immigrant tweet from Orbán and added that “Western Civilization is the target of George Soros and the Left.”

There is a particular irony to all these attacks. That’s because Soros, perhaps more than any other major philanthropist, has rejected the top-down model on which the caricatures of his philanthropy depend. In the Open Society Foundations, he created a sprawling, decentralized network of local boards in some 20 nations that were granted exceptional levels of autonomy. “The guiding ethos of the foundations is different from most [philanthropic] entities in which funding decisions are made in the center,” notes Leonard Benardo, the vice president of the OSF, and formerly its regional director for Eurasia. “That’s just how we function.” As Benardo explains, Soros’s governing philosophy insists on the primacy of local knowledge: “That’s why we have a surfeit of boards.” If Soros is a puppet master, then he’s given his marionettes some pretty long strings.

Still, it’s important to acknowledge that the strings do exist, and that there is a limit to the control Soros is willing to cede. He remains the chair of a global board that monitors the national boards and that has final authority on their grants. According to Benardo, he has rarely exercised that authority, but it exists nonetheless. Soros made this clear in a telling paragraph in an autobiographical essay in which he highlighted Open Society’s reliance on local knowledge and his willingness to defer to the judgments of local boards. He then added a significant caveat: “If I seriously disagreed with their judgment, I changed the board.” It’s also important to note that no matter how bottom-up the OSF is, Soros’s money has by definition empowered some parts of civil society over others, propping up certain organizations, public figures, and issues.

Which is all to say that the power that Soros has wielded and continues to wield as a philanthropist is undeniable. He took a new, aggressively political approach to philanthropy, one that is now embraced by a rising corps of billionaire donors, from Tom Steyer on the left to the Koch Brothers on the right, to Bill Gates somewhere in the middle. In the U.S., Soros was one of the first philanthropists to put significant money toward promoting gay marriage, opposing the death penalty, and reforming immigration law and the criminal-justice system.

Whatever one thinks of the merits of those causes, the ability of Soros and other philanthropists to use their vast wealth to exercise power over the realms of democratic deliberation is worthy of serious reflection. It’s up for debate how much sway individuals should have over public policy, but it’s almost impossible to weigh that question soberly when operating in a conspiratorial register. This suggests the second danger such narratives pose to civil society: Feverish theories about shady influence from “outsiders” obscure the real threats philanthropic power can pose to democratic institutions and norms. Even if philanthropic bogeymen are not real, there still might be good reasons to fear the dangers they actually pose.