TikTok, owned by Chinese social media giant ByteDance, announced that it will pull out of Hong Kong after Beijing imposed a new national security law that is bringing Chinese-style internet censorship to the city.

The Hong Kong government yesterday granted the police vast new powers to monitor and control online speech under the new law, which prompted a number of US tech giants to say they would suspend acting on requests from Hong Kong for user information.

“In light of recent events, we’ve decided to stop operations of the TikTok app in Hong Kong,” a TikTok spokesperson said today (July 7), without elaborating. A source cited by Reuters said the company made the decision because it is unclear if Hong Kong will “fall entirely under Beijing’s jurisdiction” after the new law.

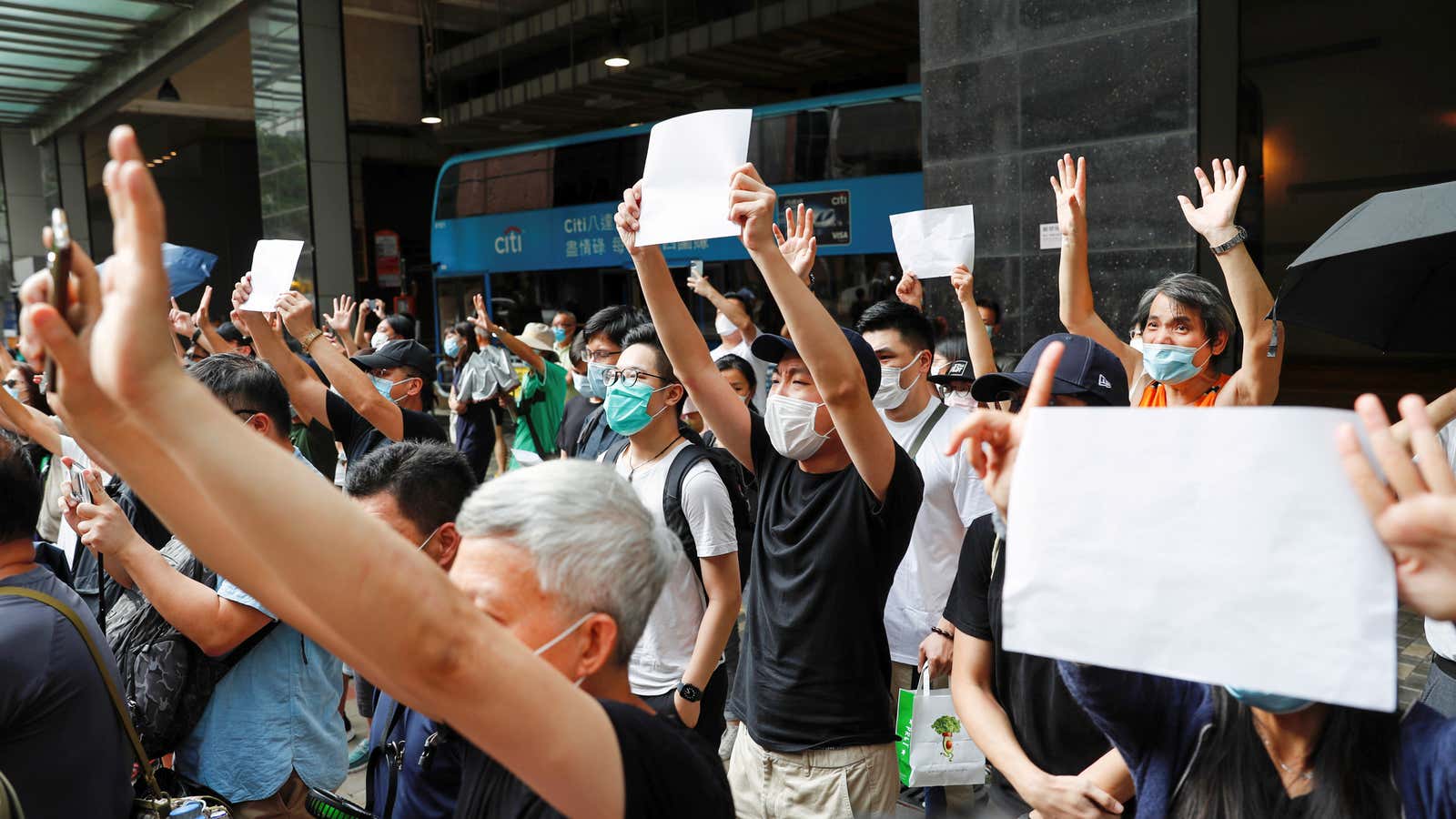

The national security law, passed last week, is Beijing’s latest effort to tighten its grip on the onetime British colony which saw anti-government protests sweep across the city starting last June. The law is written vaguely enough that any criticism of the Chinese Communist Party could plausibly be deemed a violation, and it covers essentially everyone living on this planet. In the seven days since it came into effect last Tuesday (June 30), young pro-democracy activists have fled, libraries have stopped lending books by Hong Kong protest figures, and a key rallying cry has been outlawed.

Under yesterday’s rules, the police can require internet platforms to take down content deemed threats to China’s national security. This means international tech companies in the city now face the prospect of being regulated in the same way Beijing scrutinizes tech companies in mainland China. Google, Twitter and Facebook, all of which have offices in Hong Kong, have said they have paused processing requests from the city’s law-enforcement agencies, with Facebook saying it believes freedom of expression is a “fundamental human right” and Twitter said it has “grave concerns” about the intention of the new law.

While TikTok’s separation from Hong Kong appears to go even further than the moves by US tech firms, several observers argue the decision can’t be read as the company standing up for free speech or pushing back on Beijing’s censorship. The steps being taken by Facebook, Google and Twitter affect law enforcement, while users continue to be able to use their services. TikTok’s move, instead, appears to be self-protective, to avoid being placed in the position of facing pressure to hand over user data outside mainland China.

If TikTok continued to operate in Hong Kong, it would be in a much trickier position than foreign firms. Unlike companies like Google and Facebook, which are banned in China and thus don’t count the country as a major lifeline, its parent ByteDance earns most of its revenues and has most of its employees in China. A perception of non-compliance by one of its platforms could lead the company to draw the ire of Beijing–as it has in the past. But any perception that it is compromising user privacy would thwart the company’s endeavors to allay worries about its Beijing roots from US lawmakers as it seeks to expand.

In response to such concerns, the company has stated it doesn’t censor the platform, doesn’t store user data in the mainland, and would not share such data with Chinese authorities. TikTok didn’t immediately respond to questions from Quartz seeking clarification about the exit.

Another layer of risk for TikTok comes from the fact that the platform, which promotes itself as being a lighthearted place, is starting to see an increase in political activism and expression. A number of teens, for example, posted satirical “I Love China” videos (Quartz member exclusive) to poke fun at the app’s Chinese origins, while the apps users also say they helped tank a Trump rally.

Meanwhile, compared with the statements from Facebook and Twitter, who explicitly reference individual rights as the reason for their decisions, TikTok’s statement is far more vaguely worded, and doesn’t mention the need to protect user safety, say observers.

“TikTok’s decision is a public relations exercise, not a decision based in principle. Notably, TikTok didn’t refer to any principle as being the basis for its decision to move out of Hong Kong, unlike Facebook…,” said Fergus Ryan, an analyst who studies Chinese internet at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI). Ryan argues that the exit is also an “easy decision” for TikTok, as most Hong Kongers are already wary of apps that could potentially send data back to Beijing, so there was never much of a likelihood that the app would become popular in Hong Kong, where it had only about 150,000 users as of last August.

Within days, it’s likely users in Hong Kong will no longer be able to download the app, nor continue to use it if they already have it. Instead, internet users may have to embrace their new reality by using Douyin, the heavily censored Chinese counterpart of TikTok currently available only to those in mainland China.