As cases of the coronavirus (especially the delta variant) swell, there are constant stories of people who flouted vaccination and general public health guidance and then got sick. An attendee of Hillsong Church who refused to get vaccinated dies of coronavirus; a radio host who mocked vaccinations on the air is under intensive care. These stories often provoke anger.

Even politicians who actively politicized public health measures are now frantically trying to encourage vaccination in their communities. Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey has talked about “blaming the unvaccinated” for the increase in cases and is trying to rebrand the “Trump vaccines” in a push to motivate uptake among Republicans, while simultaneously banning universities and other public institutions from requiring proof of coronavirus vaccination.

Acknowledging that these people endangered the health of others, even caused harm, is natural; blaming them and thinking they deserve sickness as comeuppance is a tricky moral posture. And it’s even trickier when people suggest turning this “blame” into policy.

There is a tangle of social, moral, and practical issues here. Politicians suddenly showing deep confidence in the vaccine deserve only limited moral credit since they are partly responsible for the vaccination uptake problem in the first place; lots of vaccination “skeptics” seem only to change position when it directly affects their red states, after ignoring the impact on New York and California. But I want to focus on a particular element: What does “blame the unvaccinated” mean and imply?

Anger is an understandable and visceral reaction; several recent articles note that vaccinated people and groups are angry because rising case rates have resulted in revisiting public health measures, and because people following public health guidance feel it’s wrong they should continue to shoulder the burden to compensate for those who flout that guidance. There is a reasonable moral issue around the fairness of having a responsible population doing work when so many are trying to ride for free on that work. Ivey and other such figures suggesting that we “blame” those shirking their responsibility look entirely reasonable (though wildly hypocritical) in that context.

Blame typically entails that some punishment or adverse consequence is justified. Pam Keith, a former Democratic nominee for a Florida congressional seat, echoed a sentiment common on Twitter: that we should suspend government benefits to unvaccinated people. Others suggest that perhaps insurance companies should increase premiums for those who decline vaccination; a nurse told the New York Times, “If you choose not to be part of the solution, then you should be accountable for the consequences.”

There are a few ways to respond to this point. One is rather technical: The post-Obamacare structure of insurance companies is supposed to prevent them from gouging patients by targeting particular risk factors, so that we don’t price some people out of the insurance market because the cost of insuring them is too high to be profitable for private insurers. (As my colleague Mia Brett points out, “If you suggest raising insurance rates for non vaccinated people [we’re] one step away from going back to justifying raising insurance rates for people with uteruses.”)

Another way of responding is straightforward and moral: There are limits to the kind of punishment that we can inflict on people, and taking away the social safety net and putting them at risk of financial and even health disaster because of their noncompliance is not an acceptable punishment for anything.

Those who want to shift costs onto the unvaccinated are advocating a particular moral position, that there should be severe and direct consequences for those who flout vaccine recommendations. Politicians and more serious political commentators have not taken to these kinds of approaches so overtly yet, but some of the existing proposals come close to doing this. For instance, it’s one thing for the government to institute a vaccination mandate for public employees; vaccinations as a general requirement for employment or school enrollment are a standard part of the business. Certain areas of public life need to be areas where people can be reasonably confident their health is being respected, at least by the government itself. If you are getting treatment for cancer, for example, then you should be reasonably confident that your medical team has done what it can to limit your exposure to infectious disease (by getting vaccinated and taking other precautions).

However, there have been proposals from ostensibly more serious people to implement partially veiled punitive measures. The Tax Policy Center has suggested that there be tax breaks given to vaccinated people. This looks better, as it’s framed as “reward people being responsible,” but it ultimately behaves the same way that “tax things we don’t like” does. “Tax cuts for X” and “tax raises for not X” look different, but rarely are from an implementation standpoint. Alternatively, professor Dov Fox noted last year that states can compel vaccination using fines, as well as restricting access to certain public accommodations.

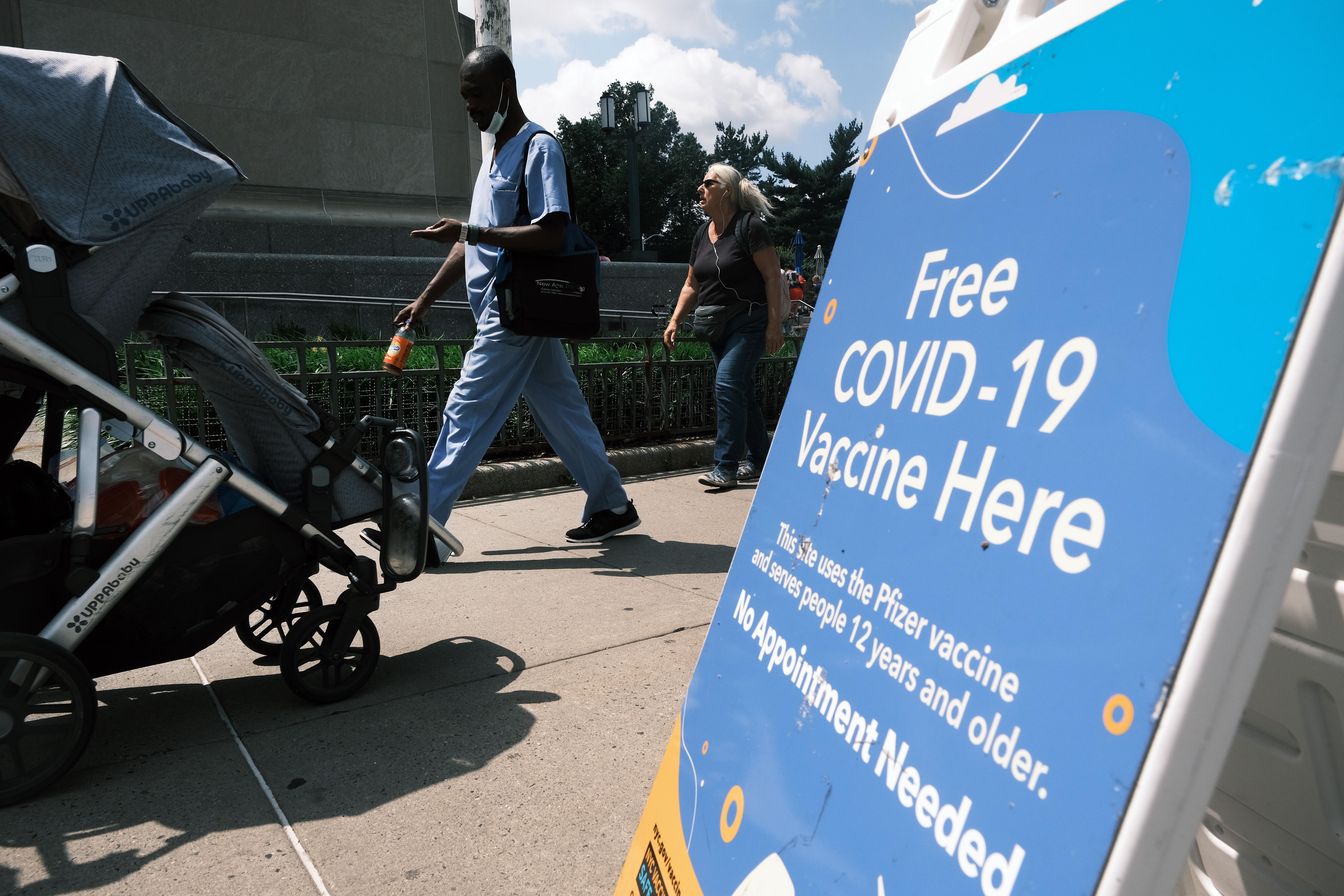

Several op-eds have been published arguing that we should be sympathetic to those who are hesitant about vaccination as a matter of practical strategy, that you vaccinate more people with honey than with vinegar (figuratively, not literally). Perhaps that is so; perhaps there is a practical argument for preferring positive public relations to punitive measures (though it’s worth noting that the two are hardly exclusive). Much of the discussion about blame also assumes that anyone who is not yet vaccinated has made an ideological choice. But many are concerned that they will have to pay money for the shot, or are unable to take the day off of work unpaid, or don’t have a ride to a clinic. Along those lines, then, there is a public policy argument that punishing the least well-off people who refuse to vaccinate is regressive and unfair, because those without the resources to easily pay financial penalties (through private insurance premium increases or loss of the social safety net or tax penalties) are also the least responsible for their vaccine hesitancy. They are very different from the well-off politicians and news figures who spent the past year selling anti-vaccination propaganda.

Even if we are talking about the most blameworthy, that doesn’t mean we can induce medical bankruptcy or deprive people of care as a punishment. Our obligations to members of our society don’t end just because they do something that is dangerous, even blameworthy.

Consequences like causing the person to be in extreme medical debt or denying them social services push against the minimum social goods to which every member of our community, regardless of their moral failures, should be entitled.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.