Could the US Postal Service improve its financial position by becoming a bank? And could it change the financial sector for the better in the process?

This idea, known as postal banking, has become increasingly mainstream over the course of 2014. And while there's no indication such a change is imminent, it could be achieved without congressional action or any new tax revenue — exactly the sort of idea activists are looking for in a time of gridlock. But why are people interested in this idea? Would it really work? Is it really legal?

We have you covered.

1) What is postal banking?

Broadly speaking, postal banking is government provision of banking services — typically relatively small-scale checking and savings accounts along with associated payment services. Historically and internationally, government-run banks have typically been paired with government-run mail services — hence postal banking.

A postal service requires a nationwide series of retail establishments, which is exactly the physical infrastructure that a basic banking operation requires. Postal services also dabble, via the sale of stamps, in a kind of quasi-financial business as part of their day-to-day business. Meanwhile, governments have often undertaken various policy initiatives to encourage thrift among their citizens and ensure a stable and credible payment system. Consequently, it's been common at various times and places for governments to permit or direct their postal services to get into the banking industry.

The US Postal Service (USPS) does not currently offer financial services, though it has in the past, and some people feel that it should again in the near future.

2) Why are people talking about postal banking now?

The current upsurge of interest in the subject of postal banking results from three separate policy conversations. One is the continued debate, post-2008, about the financial services industry and its role in society. Private sector banks do not welcome competition from a government agency, but for the exact same reason people who are inclined to take a dim view of the banking industry tend to be enthusiastic about it. Second, the private sector banking industry as currently constituted leaves millions of Americans "unbanked," which causes a number of problems in a society where possession of a bank account is necessary to participate in many mainstream economic activities.

The other issue motivating postal banking advocates is the poor financial state of the USPS.

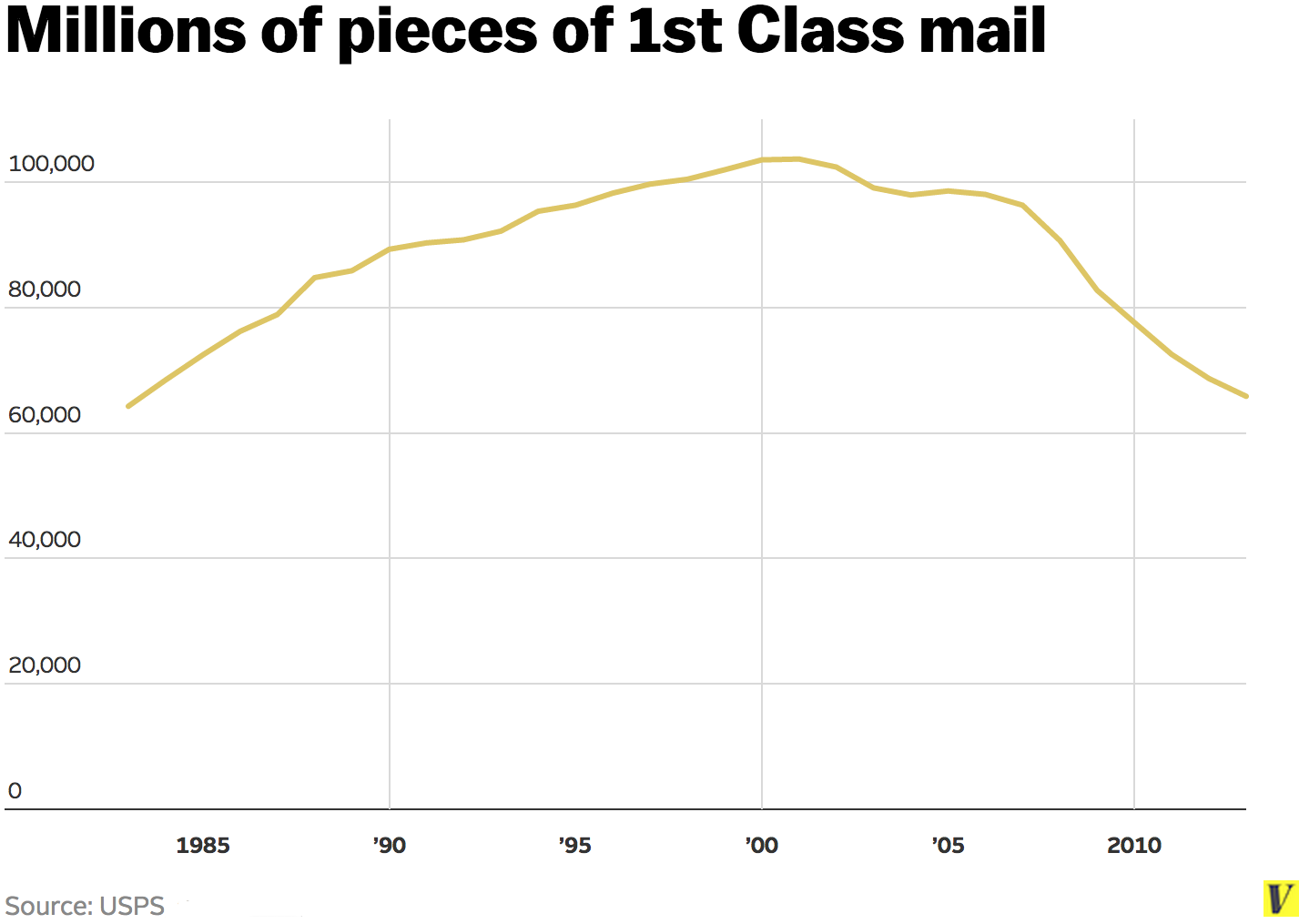

The grand bargain on which the Postal Service is founded is the idea that holding a monopoly on the right to deliver daily mail should be very lucrative. That lucrative monopoly is supposed to allow the USPS to provide some loss-making services, such as extending daily mail coverage to low-income rural areas and maintaining a truly comprehensive network of post offices. A lucrative monopoly should also allow the Postal Service to compensate its workforce relatively generously. Yet given the rise of digital communications, the USPS monopoly is becoming less lucrative over time — forcing the agency to seek a mixture of cost-cutting measures and new lines of business. Financial services could generate revenue to help USPS sustain its mission.

These different threads of interest became more intense after the January 2014 release of a white paper from the USPS Inspector General making the case for postal banking, and arguing that many financial services could be introduced without new congressional action. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) has taken up the cause of postal banking, and there's polling that indicates it's popular.

3) What forms of banking did the Inspector General propose?

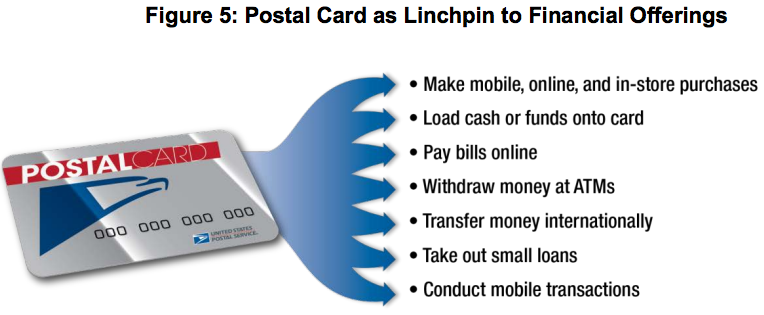

(USPSOIG)

(USPSOIG)

The IG report suggested three different levels of involvement with financial services that the Postal Service should consider.

Most basically, USPS could offer a low-fee no-interest checking account featuring a debit card. Checks could be deposited at post offices or via a smartphone app, and the postal account would allow you to pay bills or set up direct deposit. A more elaborate proposal is that "the Postal Service could partner with a bank to offer an interest-bearing savings feature on the Postal Card." A savings account, in other words.

Last, the IG suggested that the Postal Bank might make small-scale personal loans — in effect competing with payday loan operators and pawn shops.

The report estimates that $89 billion a year is spent by consumers on non-bank financial services — check cashing fees, prepaid debit card fees, payday loans, etc. — and that it's plausible to imagine the USPS capturing perhaps 10 percent of that market.

4) Which countries currently have postal banking?

Deutsche Postbank headquarters, Bonn (Eckard Henkel)

Deutsche Postbank headquarters, Bonn (Eckard Henkel)

Postal banking is reasonably common globally, though looks can be deceiving here. Germany's Deutsche Postbank, for example, though originally a postal bank is currently a private retail bank. Similarly, in Japan the postal service runs a major bank but the entire operation is supposed to be privatized by 2017. But France, Switzerland, Israel, Korea, India, New Zealand, and others continue to run postal banks.

The United States, once upon a time, had a postal bank of its own called the United States Postal Savings System, signed into law by President Taft in 1911.

In its initial form, the main purpose of the USPSS was to provide ordinary citizens with limited insurance against bank failure, as funds stashed with the USPSS were guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the US government. Following the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Company in the 1930s, this advantage went away and the system began to slowly decline after 1947. What really did it in, however, was the rising inflation rate of the 1960s — with interest rates capped at 2 percent, it became a very unattractive savings vehicle and was essentially shuttered in 1967.

5) Is there any postal-themed music I can listen to?

Indeed! In 2003, Ben Gibbard, Jimmy Tamborello, and Jenny Lewis recorded an album under the name The Postal Service. Here's "The District Sleeps Alone Tonight"

The United States Postal Service did not take too kindly to this appropriation of their name and sued the band, though the matter was eventually settled.

6) How many unbanked people could postal banking help?

Right now, about ten percent of US households don't have so much as a checking account. Jessica Silver-Greenberg and Stephanie Clifford reported in 2013 for the New York Times that many employers now pay such people through high-fee prepaid debit cards that leave some low-wage workers earning less than the minimum wage in take home pay. Others have to rely on high-fee check cashing shops. And for many Americans of modest means, lack of access to bank credit means depending on very expensive payday loan shops.

According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, ten percent of American Census tracts have zero bank branches within 5 miles of their center of population. Among those tracts, 76 percent have a Post Office that's closer than the nearest bank. So a postal bank could easily improve the convenience of banking for people who live in areas where it's not profitable to open a branch.

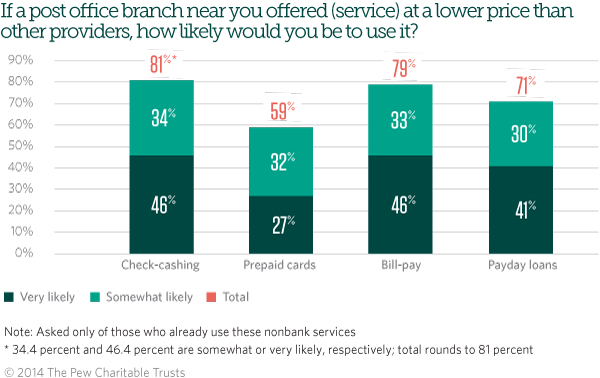

(Source: Pew Charitable Trusts)

(Source: Pew Charitable Trusts)

Pew also found, unsurprisingly, that the unbanked say they would be interested in using USPS-provided financial services if provided at a lower price than is currently offered by payday lenders and check cashers.

Postal banking enthusiasts believe the USPS should be able to undercut those prices, since they'd be essentially piggybacking on existing real estate assets rather than needing revenues sufficient to cover those real estate costs and provide a profit for investors.

7) What are some arguments against postal banking?

The most general argument is that just because the government could potentially enter some business with success doesn't mean that it should. Having government agencies compete with private firms could be unfair to the companies and distort the larger economy.

Concerns grow more serious the more deeply involved with financial services the postal bank would become. The most aggressive proposal — in which the postal bank competes with payday lenders to offer personal loans — carries particular dangers. Private banks have been known to badly mishandle the risks of their loan portfolio. These problems could be even more severe in a government-run enterprise where there'd be no market discipline at all around reckless lending. But once the government commits to running a public utility bank, it can't very well let it collapse in bankruptcy. You could end up with the kind of bailout situation that affected mortgage lending giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

A step in the direction of postal banking would also to a large extent be swimming against the global tide.

Postal banking systems are reasonably common today, but they were more common in the past. The recent trend has been toward the privatization of postal services, and the deregulation of postal markets — moves that reflect daily mail delivery's diminished significance in the modern world.

8) Would postal banking fix USPS' financial problems?

It would certainly help, in the sense that any injection of new revenue would inherently be useful. But the underlying source of the USPS' problems is not mysterious — the organization is built on the assumption that it possesses a lucrative monopoly over the delivery of a large and growing volume of daily mail. Now that mail volume has gone into decline, the Postal Service is bound to have trouble covering its costs.

Thus far, the agency has relied mainly on cutting staffing levels, seeking compensation givebacks from unions, and efforts to grow its parcel delivery business in which it competes with Fedex, UPS, DHL, and others.

These efforts have paid dividends, but don't change the basic reality that the simplest response to the declining value of the First Class Mail franchise would be to reduce the scope of the operations that the monopoly is expected to finance. Yet thus far Congress has refused to allow USPS to cease Saturday mail deliveries or close low-value rural Post Offices. Extra money from banking or other non-postal businesses would, of course, help close the gap. But in a sense, nothing will really resolve the underlying issue unless the agency is allowed to realign its required level of service provision with its core funding base.

9) Is postal banking legal?

Superficially, it is not. The Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act of 2006, among other things, bars the USPS from entering new non-postal businesses. (This is also the law that's saddled USPS with unusually onerous pension funding obligations). But the Inspector General's report argues that the kind of financial services it's advocating don't really constitute new businesses. The Postal Savings System may be shuttered, but remnants of the postal role in finance remain in the form of money orders and a present-day arrangement to sell American Express prepaid debit cards at Post Offices.

Of course, if the postal bank got too aggressive there would likely be a congressional move to shut it down. But as with so much else in life these days, in the real world a Postal Service that wanted to get into financial services could probably count on congressional gridlock to let it happen.

In practice, the decision would likely be in the hands of the USPS Board of Governors, which is supposed to have nine members in addition to the Postmaster General and the Deputy Postmaster General. Yet currently five of those seats are unoccupied, and the Obama administration has not managed to seat a single person on the board since his inauguration in January 2009. The result is a board dominated by Republican appointees who are unlikely to give the thumbs up to anything other than cutbacks at the postal service. A determined president, however, likely does have the legal authority to make at least some form of a postal bank happen.