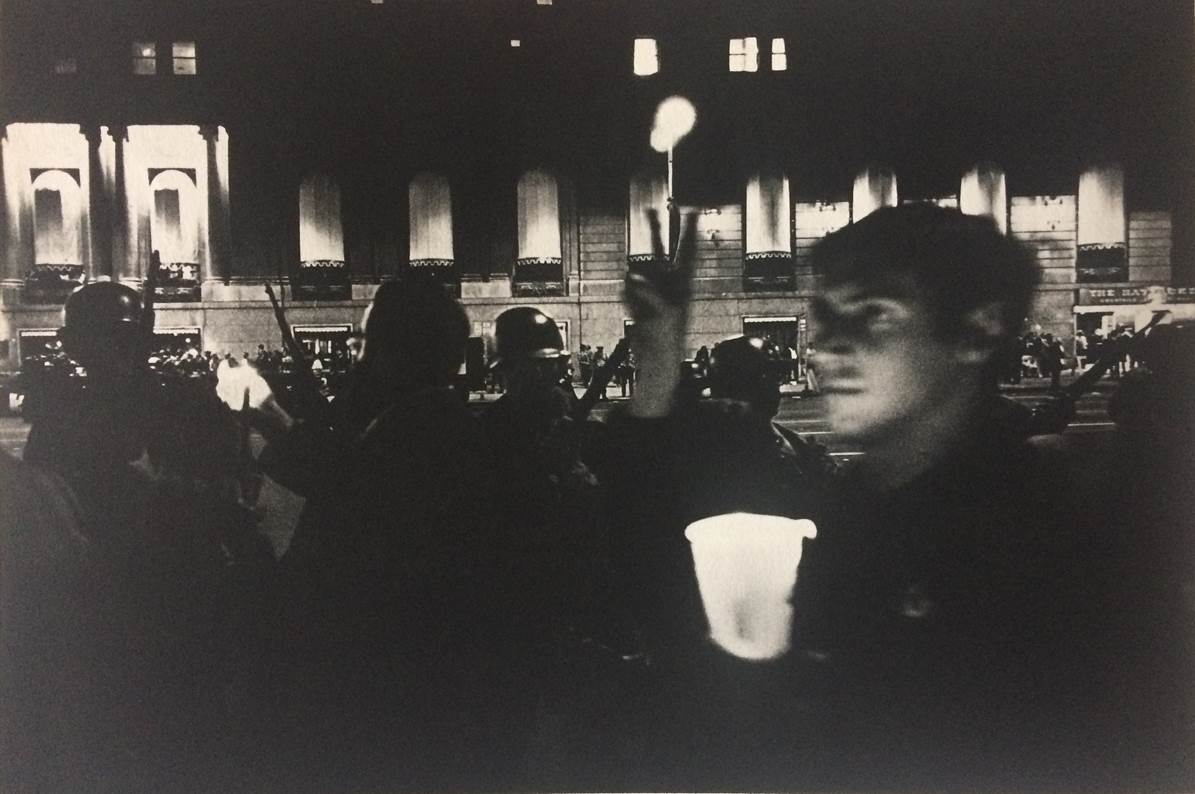

Feature photo by David Douglas Duncan. Used with permission of the Harry Ransom Center.

At the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, police riots erupted across the city in response to anti-war demonstrators. In this piece, Arthur Miller reflects on the aftermath of the riots and describes a candlelight walk and vigil that he took with other Democratic delegates on the night of August 28th, by Grant Park to the Conrad Hilton Hotel. In many ways, his keen observations on the nature of violence, the failures of the political party machine, and the act of protest speak directly to the present day.

*

There was violence inside the International Amphitheater before violence broke out in the Chicago streets. One knew from the sight of the barbed wire topping the cyclone fence around the vast parking lot, from the emanations of hostility in the credential-inspecting police that something had to happen, but once inside the hall it was not the hippies one thought about anymore, it was the delegates.

Violence in a social system is the sure sign of its incapacity to express formally certain irrepressible needs. The violent have sprung loose from the norms available for that expression. The hippies, the police, the delegates themselves were all sharers in the common breakdown of the form which traditionally has been flexible enough to allow conflicting interests to intermingle and stage meaningful debates and victories.

The violence inside the amphitheater, which everyone knew was there and quickly showed itself in the arrests of delegates, the beatings of newsmen on the floor, was the result of the suppression, planned and executed, of any person or viewpoint which conflicted with the president’s. There had to be violence for many reasons, but one fundamental cause was the two opposite ideas of politics in this Democratic party.

The professionals—the ordinary senator, congressman, state committeeman, mayor, officeholder—see politics as a sort of game in which you win sometimes and sometimes you lose. Issues are not something you feel, like morality, like good and evil, but something you succeed or fail to make use of. To these men an issue is a segment of public opinion which you either capitalize on or attempt to assuage according to the present interests of the party.

To the amateurs—the McCarthy people and some of the Kennedy adherents—an issue is first of all moral and embodies a vision of the country, even of man, and is not a counter in a game. The great majority of the men and women at the convention were delegates from the party to the party.

Nothing else can explain their docility during the speeches of the first two days, speeches of a skull-flattening boredom impossible to endure except by people whose purpose is to demonstrate team spirit. “Vision” is always “forward,” “freedom” is always a “burning flame,” and “our inheritance,” “freedom,” “progress,” “sacrifices,” “long line of great Democratic presidents” fall like drops of water on the head of a tortured Chinese.

And nobody listens; few even know who the speaker is. Every once in a while a cheer goes up from some quarter of the hall, and everyone asks his neighbor what was said. For most delegates just to be here is enough, to see Mayor Daley in the life even as the TV cameras are showing him to the folks back home. Just being here is the high point, the honor their fealty has earned them.

They are among the chosen, and the boredom of the speeches is in itself a reassurance, their deepening insensibility is proof of their faithfulness and a token of their common suffering and sacrifice for the team. Dinner has been a frankfurter, the hotels are expensive, and on top of everything they have had to chip in around a hundred dollars per man for their delegation’s hospitality room.

The tingling sense of aggressive hostility was in the hall from the first moment. There were no Chicago plainclothes men around the Connecticut delegation; we sat freely under the benign smile of John Bailey, the Democratic National Chairman and our own state chairman, who glanced down at us from the platform from time to time. But around the New York delegation there was always a squad of huskies ready to keep order—and indeed they arrested New Yorkers and even got in a couple of shoves against Paul O’Dwyer when he tried to keep them from slugging one of the members. Connecticut, of course, was safely machine, but New York had great McCarthy strength.

The McCarthy people had been warned not to bring posters into the hall, but at the first mention from the platform of Hubert Humphrey’s name hundreds of three-by-five-foot Humphrey color photos broke out all over the place. By the third day I could not converse with anybody except by sitting down; a standing conversation would bring inspectors, sometimes every 15 seconds, asking for my credentials and those of anyone talking to me. We were forbidden to hand out any propaganda on the resolutions, but a nicely printed brochure selling the Administration’s majority Vietnam report was on every seat.

We were the crowd in an opera waiting for our cue to shout in unison when the time for it came. First depression and then anger began moving into the faces of the McCarthy people.And the ultimate mockery of the credentials themselves was the flooding of the balconies by Daley ward heelers who carried press passes. On the morning before the convention began, John Bailey had held up 22 visitors’ tickets, the maximum, he said, allowed any delegation, as precious as gold. The old-time humor of it all began to sour when one realized that of 7.5 million Democrats who voted in the primaries, 80 percent preferred McCarthy’s and/or Robert Kennedy’s Vietnam positions.

The violence in the hall, let alone on the streets, was the result of this mockery of a vast majority who had so little representation on the floor and on the platform of the great convention. Had there never been a riot on Michigan Avenue the meeting in the amphitheater would still have been the closest thing to a session of the All-Union Soviet that ever took place outside of Russia. And it was not merely the heavy-handed discipline imposed from above but the passionate consent from below that makes the comparison apt.

On the record, some six hundred of these men were selected by state machines and another six hundred elected two years ago, long before the American people had turned against the Vietnam war. If they represent anything it is the America of two years past or the party machine’s everlasting resolve to perpetuate the organization. As one professional said to me, “I used to be an idealist, but I learned fast. If you want to play ball you got to come into the park.”

Still, another of them came over to me during the speech of Senator Pell, who was favoring the bombing halt, and said, “I’d love to vote for that but I can’t. I just want to tell you.” And he walked away. Connecticut caucused before casting its vote for the administration plank. We all, 44 of us, sat in a caucus room outside the great hall itself and listened to Senator Benton defending the bombing position and Paul Newman and Joseph Duffey attacking it. The debate was subdued, routine.

The nine McCarthy people and the 35 machine people were merely being patient with one another. One McCarthy man, a teacher, stood up and with a cry of outrage in his voice called the war immoral and promised revolution on the campuses if the majority plank was passed. Angels may have nodded, but the caucus remained immovable. Perhaps a few were angry at being called immoral, in effect, but they said nothing to this nut.

But when the roll was called, one machine man voted for the minority plank. I exchanged an astonished look with Joe Duffey. Another followed. Was the incredible about to happen?

We next began voting on the majority plank, the Johnson position. The machine people who had voted “Yes” on the minority plank also voted “Yes” on the majority plank. The greatness of the Democratic party is its ability to embrace conflicting viewpoints, even in the same individuals.

Having disposed of Vietnam, Mr. Bailey then suggested the delegation take this opportunity to poll itself on its preference for a presidential candidate, although nominations had not yet been made on the floor of the convention. This, I said, was premature since President Johnson, for one, might be nominated by some enthusiast and we would then have to poll ourselves all over again. In fact, I knew privately that William vanden Heuvel, among others, was seriously considering putting up the president’s name on the grounds that the Vietnam plank was really a rephrasing of his program and that he should be given full credit as its author rather than Humphrey, who was merely standing in for him.

But Mr. Bailey merely smiled at me in the rather witty way he has when his opponent is being harmlessly stupid, and Governor Dempsey, standing beside him behind the long table at the front of the room, assured all that as head of the delegation he would see to it that in the event of a nomination on the floor of any candidate other than Humphrey, McCarthy, and McGovern, we would certainly be allowed to change our votes.

Immediately a small man leaped to his feet and shouted, “I nominate Governor Dempsey!” The governor instantly pointed at him and yelled, “Good morning, Judge!” This automatic reward of a seat on the bench, especially to a man obviously of no distinction, exploded most of the delegation—excepting the indignant teacher—into a burst of laughter and the governor and his nominator swatted at each other in locker-room style for a moment. Then seriousness returned, and resuming his official mien of gravity, the governor ordered the polling to begin.

The nine McCarthy delegates voted for McCarthy and the rest for Humphrey, and there was no doubt of an honest count. It may be a measure of the tragedy in which both factions were caught that when, later on, the governor was handed teletyped reports of the Michigan Avenue riots, his face went white, and he sat with his head in his hands even as it became clearer by the minute that Humphrey and the administration would be victorious. After two nights on the floor, whatever trends and tides the TV commentators might have been reporting, one felt like a fish floating about in still water.

Nothing had been said on either side that aroused the slightest enthusiasm. The water above was dark, and whatever winds might be raising waves on the surface did not disturb the formless chaos, really the interior leaderlessness of the individual delegates. We were the crowd in an opera waiting for our cue to shout in unison when the time for it came. First depression and then anger began moving into the faces of the McCarthy people as the speeches ground on. Some of us had campaigned all over the state and the nation to rouse people to the issues of the war, and in many places we had succeeded.

There was no trace of it here and clearly there never could have been. The machine had nailed down the nomination months before. We had not been able even to temper the administration’s Vietnam plank, not in the slightest. The team belonged to the president, and the team owned the Democratic party. As I sat there on the gray steel chair, it was obvious that we could hardly have expected to win. Behind Connecticut sat two rows of Hawaiians. Middle-aged, kindly looking, very polite, eager to return a friendly glance, they never spoke at all.