The road to exile

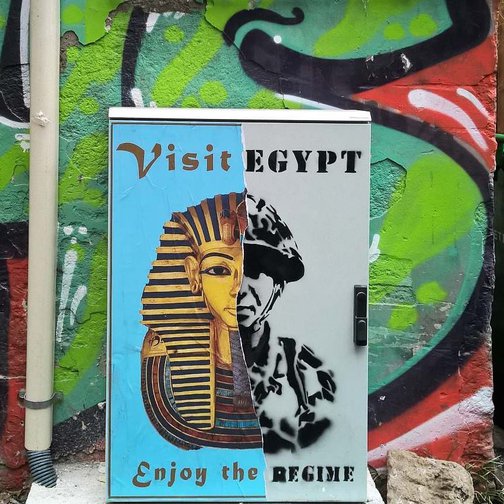

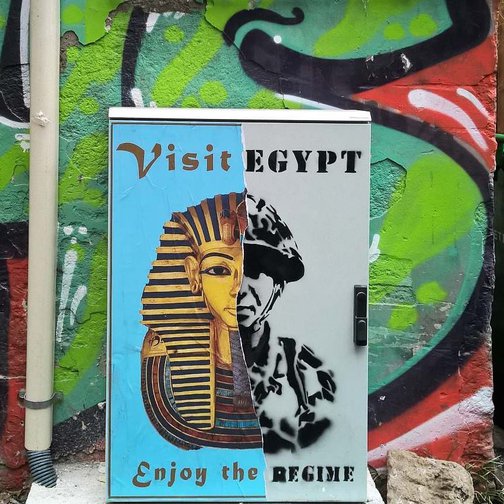

A love letter to exiles about revolutions, authoritarianism, and the brutal dictatorship in Egypt.

Closing Scene

December 15th 2019 , the Egyptian autocrat Abdel Fattah Al Sissi gave a speech in one of the many youth conferences that the regime likes to use for internal propaganda. In this speech, he laid the blame on the rise of political violence in the region squarely on the shoulders of the mass protests that erupted in 2010, onwards.

I was asked to comment on his speech by Al Araby TV. I highlighted the fallacy of his logic that ignores the role of state violence and dictatorships in igniting the civil wars that have wracked the region, and the possible explosive situation in Egypt, due to the complete closure of public space.

As I laid my head on my pillow, I could not help but think how surreal my life had become. A sense of estrangement and guilt washed over me. For even though I was in exile, at least I was safe from being thrown in an overcrowded dark cell, where poor sanitation, medical negligence and the cold of winter would have wreaked havoc on both my health and sanity. However, like many exiles, I suffered from marginalization, social isolation, and the never-ending nostalgia of home. I closed my eyes, and as is my habit in nights likes these, I dreamed of it.

Scene 1

November 20th 2018, the TV presenter Nashat Aldhihi attacks me, personally, as well as the Carnegie Endowment of International Peace, on his TV show. The TV channel TeN TV is owned by the security services, making me acutely aware that I am on their radar.

We’ve got a newsletter for everyone

Whatever you’re interested in, there’s a free openDemocracy newsletter for you.

Like many exiles, I suffered from marginalization, social isolation, and the never-ending nostalgia of home

The article that irked the security services was an evaluation of performance of the Egyptian economy. This article claims that the current economic policies are fuelling a spiralling debt crisis, which is exacerbated by uncontrolled military spending, coupled with mega infrastructure projects with dubious economic benefit.

The numerous articles that I wrote about extra judicial killings and various human rights abuses did not garner such a furious reaction. A month before that, on the 22nd of October, Abdul Khalik Farouk the author of a critical book on the Egyptian economy was arrested and copies of his book were confiscated. He stands accused of publishing false news, a malleable charge used to silence the opposition.

Scene 2

January 25th 2016, the Italian PhD student Giulio Regeni disappears in Cairo. He was in the middle of conducting field work for his PhD on Egyptian labour unions. His body was later found in a ditch next to the Cairo-Alexandria Desert road, with horrific torture marks. It was later determined that after enduring torture for several days, a blow to the back of the neck killed him.

On December 4th 2018, the Prosecutor General of Rome placed five members of the Egyptian police and the National Security Agency (NSA) on a list of suspects related to the abduction, torture, and murder of Giulio Regeni. In March 2016, in an attempt to cover up its involvement, the Egyptian security forces stated that it liquidated a gang of five men, accused of kidnapping and torturing Regeni.

The security forces were later forced to retract this statement, as it became clear that it is a flimsy attempt for a cover-up.

The murder of Regeni proved no one is safe, not even Europeans

The fate of these men is rarely discussed, as if their lives, families, and subsequent death are insignificant. Another life squashed under the heels of tyranny. The murder of Regeni proved to be a personal watershed, as it contained a message to critics of the regime. Namely, no one is safe, not even Europeans, who were off-limits during the Mubarak years. Thus, even the possession of a European passport will not offer protection nor reprieve.

Scene 3

July 24th 2013, the then Minister of Defence Sissi, asks for popular mobilization and mass protests to authorize him to fight “terrorism”. At this time, the supporters of the deposed President, Mohamed Morsi, are camped out in Raba’a and Nahad squares in Cairo.

This was the prelude for the worst massacre of protestors in modern Egyptian history, and a founding moment for the neo-military regime. At least 817 protestor were killed. This massacre led to the extreme polarization of the Egyptian political system, as well as a cycle of violence between an increasingly radicalized insurgency and the security forces leading to hundreds of deaths and the popularization of the war on terror rhetoric, which resulted in the imprisonment of thousands in brutal prison conditions.

These are the conditions that led to the death of Mohamed Morsi, on June 17th 2019, in a courtroom in Cairo.

On August 2013, I wrote my first article for openDemocracy, as I attempted to make sense of what was about to come, and to, in my own way, attempt to have an influence on the course of events, or at least, this is what I told myself.

Looking back, I can honestly say that it was an attempt to alleviate a sense of guilt that was threatening to overwhelm me, since I was sitting on the side lines, as the tragedy unfolded. A sense of guilt that could only be alleviated by taking action that would lead to what feels like an endless state of social and physical exile.

Opening Scene

Friday 28th of January 2011, what would later be known as the Friday of anger: The anticipation is high as the calls for protest to bring down the regime are posted over social media, in an attempt to repeat the Tunisian uprising. I sit in my office, in a small Swiss city, overlooking the mountains as I am glued to my Facebook page, attempting to follow updates from the ground.

My hope rose that it was time to return to rebuild what the dictatorship had destroyed.

My British boss walks in, and attempts to defend the Mubarak dictatorship as “benign” and secular, a much better alternative than the Muslim Brotherhood. I pay him no heed, even though I would find myself in similar conversations, not only with Europeans, but with fellow Egyptians too, as I defend the popular uprising.

For the next three weeks, I am transfixed on the TV screen, until the 11th of February 2011, when Mubarak steps down. My mother calls me the moment he does, as it seems that my time in Europe is ending. It had been only two years since I left to study, and my hope rose that it was time to return to rebuild what the dictatorship had destroyed.

Little did I know that the words of the great Edward Said would resonate as the years passed, “exile is strangely compelling to think about but terrible to experience. It is the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home: its essential sadness can never be surmounted”. As of now, I still visit home, in my dreams.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.