The numbers we use to measure economic health are funny things. We treat them like windows onto objective reality, but they are actually very human artifacts. Encoded within them are hidden moral and political assumptions about how the world is supposed to work — assumptions that should always be ripe for challenge.

The most famous illustration came from Robert F. Kennedy, speaking in 1968 about the number we call the “gross national product.” We presume that when it is bigger, America is better. But as Kennedy pointed out, it also counts “air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage,” “special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them,” “the destruction of the redwood,” “napalm nuclear warheads,” and “television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children” — “everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

We also presume that economic statistics can be compared meaningfully from decade to decade. But this also is not always true. Take the “poverty rate”: It’s a matter of apples and oranges, because the statistic is calculated based upon the price of a basket of certain foods and was invented in 1962, when food was a third of the typical family’s budget. Now it is one-seventh.

And we pretend metrics that function reasonably well in normal times mean the same thing when things are not normal at all. It seems wonderful when nearly every adult has a job — except during a pandemic. Nations that chose to subsidize wages to keep their citizens out of crowded offices may have wreaked havoc with their “unemployment rates.” But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t the right thing to do.

Given all this, what to make of the fact that the number we call the “consumer price index” is 5.4 percent, its highest in 13 years, when it was but 0.6 percent a year ago?

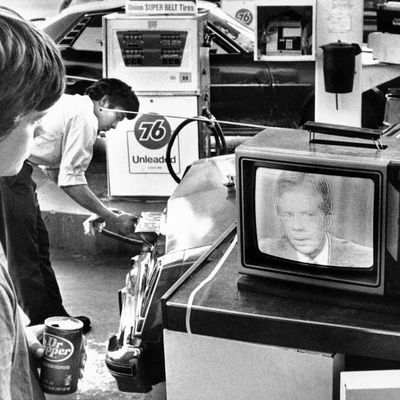

The rise in the CPI — this country’s gold standard for measuring inflation — has occasioned hand-wringing in certain quarters that we might going back to the bad old days. Specifically, the years in the mid- to late 1970s, when the CPI ballooned above 10 percent and occasionally higher than 14 percent, after a 20-year period in which the CPI averaged 2.4 percent.

But the current state of the CPI has absolutely nothing to do with the CPI in the 1970s. In fact, the CPI of the ’70s didn’t mean what it was taken to mean even then. And there is a great hazard when politicians and pundits, unwittingly or not, make this mistake.

Return with to me to those times, when experts and politicians from both political parties proffered three major explanations for the crisis, which had been rendered even more baffling by the fact that it was joined by skyrocketing unemployment (back then, economists believed it impossible for high unemployment and high inflation to coexist):

• Fiscal deficits: The American government was “spending money we don’t have,” President Jimmy Carter said, and “borrowing money to pay the difference.” So the way to fight it was budget cuts.

• Lax monetary policy: Inflation was “a tax imposed by Washington in the name of easy money,” as Ronald Reagan, Carter’s right-wing rival at the time, put it. So the way to fight it was “to stop printing money.”

• Unions: They had become too powerful, and employers too supplicant to them, agreeing to contracts with automatic “cost of living adjustments,” or “COLAs,” that businesses now had to raise prices to pay for. So the unions should ask for less, Carter insisted, as a “sacrifice for the common good.”

Carter would sometimes pin responsibility on the “costs which private industry bears as a result of government regulations” — and Reagan, of course, heartily agreed with that.

When ideological rivals converge so dramatically upon common assumptions on controversial public questions, something deeper is going on than mere politics. In the ’70s, when it came to inflation, that something was cultural.

I often wondered, when I was researching my most recent book on Reagan, why exactly “double-digit inflation” became such a defining issue of the time — the top voting issue in the 1980 presidential election, in fact. A banana or a Buick costing one-tenth more every 12 months doesn’t exactly seem the stuff of world-historic melodrama.

It’s not that it isn’t palpably anguishing for a family on a tight budget to be forced to stretch a dollar further every year — but many ordinary Americans didn’t have to worry about that. Union workers did have those COLAs, while employers raised wages for nonunion workers, too, to keep them from finding other jobs or forming unions themselves. For people paying down fixed-rate mortgages, inflation was a boon, since it allowed them to pay back their loans with cheaper dollars.

It was only recently that I came to a somewhat satisfying answer to my inflation question, thanks to this summer’s blip. And it is only a blip, a onetime distortion: supply-chain shocks caused by the pandemic are working their way through a global economy whose distinguishing feature is how hyperefficient it is at moving goods around the world — in normal times. But now, precisely because the whole thing is so intricately optimized and specialized, small disruptions can reverberate into major ones, so that, for example, for much of this spring and summer, lumber prices more than doubled. Soon enough, the system will return to its previously efficient equilibrium, or possibly even an improved equilibrium, as systems are rebuilt to allow for more resiliency the next time such a global shock arrives.

Things felt very different in 1979. Then, the favored metaphor of elites warning about what inflation meant was the “spiral.” As in, “spiraling out of control.” As in, things could never go back to any predictable equilibrium, because instead of higher prices reducing demand, they would accelerate demand, because people would simple buy buy buy, only more quickly than ever before, to beat future price hikes, in an ever widening gyre, and just like William Butler Yeats predicted, the center simply would not hold.

Think I’m exaggerating? Look again at those explanations for the inflation of the 1970s. These were things susceptible to uncontrolled spiral: Deficits would demand greater interest payments, spiraling into greater deficits; unions would build on inflationary contract concessions to demand yet greater concessions; both politicians and Federal Reserve chairmen might respond to economic downturns by turning on the money spigot, and then, if that did not work, loosening it even more.

Note, however, the explanation for inflation that was not particularly prevalent at the time: oil. Which was the actual main reason inflation skyrocketed. Between 1948 and 1973, largely for geopolitical reasons — the countries that produced oil were veritable colonies of the rich industrial powers — the price of oil declined in real terms. World demand, naturally, exploded, from 8.7 billion barrels a day in 1948 to 42 million barrels a day in 1972 — just in time for the countries that produced the oil to decide that this precious resource beneath their sand and soil was theirs to dispense as they wished.

First, the Arab oil embargo punished the U.S. for supporting Israel in the 1973 Yom Kippur War, and the price of a barrel of oil went from $2.70 that September to $10.11 the following summer. Then, in 1979, the shock came from Iran, first inadvertently, as the Shah’s regime fell to strikes and chaos, then intentionally, as the successful Islamic revolutionaries decided they had other priorities than pumping out oil as quickly as the West might have preferred. Oil went from $14.85 at the end of 1978 to $39.50 in the middle of 1980.

Consumption of imported petroleum in the U.S. doubled between the two shocks. No wonder the price of everything went up. It also did in countries going through none of the changes upon which America’s elites blamed our inflation.

So why did our elites tell a different story?

Listen to one of them. Arthur Burns was chairman of the Federal Reserve between 1970 and 1978. In 1979, he spoke at conference of central bankers, to whom he insisted he “could have restricted money supply and created sufficient strain in the financial and industrial markets to terminate inflation with little delay.” Why didn’t he? Because, he said, the Federal Reserve was “caught up in the philosophical currents that were transforming American life and culture.”

What philosophical currents did he mean? President Carter helps clarify. When he gave speeches about what it would take to break the back of inflation, he would deploy a favorite quotation, from a speech Walter Lippmann gave on the eve of World War II: “You took the good things for granted. Now you must earn them again. … For every good you wish to preserve, you will have to sacrifice your comfort and ease.”

One way Carter advanced that goal was by instituting restrictions that made it harder for people to use credit cards, because “just as our government has been borrowing to make ends meet, so have individual Americans,” which will “just make the problem worse.” He announced them during a March 1980 speech explaining why, three months after submitting a budget he had earlier described as “austere,” he was submitting a new one that was even more austere, cutting aid to states and cities, welfare spending, and funding for mass transit.

Again, such conclusions were heard from all sorts of politicians. One candidate challenging Carter for the Democratic nomination in 1980, Jerry Brown, advocated a balanced-budget amendment to the United States Constitution. Another candidate, liberal Republican John Anderson, told an interviewer that the next president “is going to have to wear something of a hair shirt. He may have to be a little reminiscent of the prophet Jeremiah, in the sense that he issues a few lamentations about what can happen to the country and to the world if we don’t exhibit a willingness to endure some measure of sacrifice.” Reagan gave the consensus his own spin: “We don’t have inflation because the people are living well. We have inflation because the government is living too well.”

Reagan’s version was convenient, because the prescription that followed suggested most Americans would not have to sacrifice anything — just those non-middle-class, nonwhite people who relied upon government spending to protect them from the ravages of the marketplace.

Nonetheless, the story they all told was fundamentally the same: Like naughty children, what America and its institutions needed was discipline. Budgetary austerity was the confident counsel of virtually every elite voice — in the absence of any evidence that it would work. “If President Carter wants to move fast on inflation he has only one lever that will make much difference,” the Washington Post’s editorialists said. “He will have to start cutting his budget, rapidly and severely.” Newsweek said “a balanced budget would have almost magical significance.”

Indeed, that was the counsel even among those who openly admitted that no one knew if it would make a difference, like the New York Times editorialists who insisted belts needed to tighten, even if “nobody any longer knows for sure” how to slow inflation — adding that at least the result might be a budget surplus. “The extra revenue could be used to fight inflation further, through tax cuts,” they said. There was no evidence that would work, either.

At so, you have to ask: What were these people really talking about when they talked about inflation?

The conclusion I’ve drawn is that this was a form of moral panic. The 1970s was when the social transformations of the 1960s worked their way into the mainstream. “Inflation spiraling out of control” was a way of talking about how more permissiveness, more profligacy, more individual freedom, more sexual freedom had sent society spiraling out of control. “Discipline” from the top down was a fantasy about how to make all the madness stop.

To get a sense of how culturally conditioned this response was, observe what happened in the fall of 1979 when a new Federal Reserve chair, Paul Volcker, finally did do what Arthur Burns said he couldn’t do, for fear of getting crosswise with America’s dissolute philosophical currents. He instituted reforms that radically squeezed the money supply, which Newsweek called, approvingly, “radical shock treatment for the economy.” He was greeted with near universal acclaim — and not just from elites. “It hurts, but maybe we needed it,” one man on the street told an interviewer.

A prominent liberal journalist noted how America “yearns for a strong-arm leader to curb its profligate habits.” Another, Nicholas von Hoffman, profiled Volcker for the New York Times Magazine, saying that his “predecessors were cowards” and that the presidents who hired them lacked “self-restraint.” But Volcker would “stand his ground.” (“His presence alone — he’s 6‐feet‐7, and weighs 240 — is imposing.”) That article happened to be followed in the New York Times Magazine with another arguing that the “‘no-fault’ attitudes of the past decades … must yield to a new era in which Americans will discover ‘personal guilt’ — the acceptance of individual responsibility.”

America needed “discipline.” Discipline is what Paul Volcker delivered. And what happened to the American economy?

The Great Inflation, indeed, abated — over an excruciatingly slow four years. In the interim, the economy shed an estimated 2.4 million manufacturing jobs, and unemployment climbed from 6 percent the month of Volcker’s shock, to 7.5 percent in a year, then above 10 percent for ten straight months in 1982 and ’83. It didn’t settle below its pre-shock levels until 1987. One of the few dissenting voices from the indulged-child paradigm, Robert Solow of MIT, proved prophetic: “It’s burning down the house to roast the pig,” he said.

All this without any certainty that Volcker’s monetary discipline deserved credit for inflation’s eventual dissipation in the first place. It could just have been the return of petroleum to normal market conditions after the never-to-be-repeated events of 1973 and 1979. Or something else. It is a hard thing to know, and economists still debate it.

One thing, however, is not debatable: Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan’s shared conclusion that budget deficits drive inflation has proven as intellectually sound as the doctrine that character is determined by the shape of the skull. It wasn’t even a sensible argument to make back then. After all, in 1974, when budget deficits were small, inflation exploded; by 1984, budget deficits had exploded, and stayed high, while inflation remained negligible for the next 37 years.

That is to say, until now. When, naturally, those who never met an argument for government austerity they didn’t like — or a story about society spiraling out of control, for that matter — have responded to this onetime, COVID-driven inflation blip as if garbed in fat ties and mammoth lapels, like it’s the 1970s all over again. It’s the “top line of the messaging strategy congressional Republicans are rolling out” for 2022, Politico reports. Here’s Senator John Barrasso of Wyoming: “Families are already paying for Democrats’ inflation from the gas pump to the grocery store. Now they want to drown the country in another tax and spending spree.”

It makes no sense, and no liberal should take it seriously — let alone be seduced by it into balking over Biden’s spending plans. The CPI in the summer of Olivia Rodrigo simply means something very different than it did in the summer of Disco Demolition.

As the economics journalist Binyamin Appelbaum points out, many of the ways inflation used to negatively affect ordinary Americans have been reformed out of existence. Income tax rates are indexed to inflation, eliminating the “creep” that used to rocket middle-class Americans into higher tax brackets, even as their incomes remained the same in real terms. Social Security payments are now indexed to inflation as well. The interest rates banks paid used to be severely capped, but no longer are.

There is, however, one conspicuous population hurt by inflation in the same way they might have been in the 1970s: investors, especially investors in bonds. These were, naturally, the people the commentators and politicians were listening to, including the “veteran moneyman” who told Newsweek, at a time when Argentina’s inflation rate was 600 percent, that “[w]e’re in a South American inflationary environment now.” Or the one who got inside the head of Missouri congressman Dick Gephardt, who told a reporter, “When you have bank executives come in and say, ‘We’re getting close to bank lines,’ people get frightened, If ever there was a time in recent history to balance the budget, this is it.” Weimar was just around the corner.

It was nonsense even then. It’s far more nonsensical now. As America finally decides to spend more on what “makes life worthwhile,” including the better roads, cleaner power, and affordable child care and college in President Biden’s legislative plans, dubious stories about what inflation used to mean should be the last thing to stand in the way.