Whites-only covenants still exist in many mid-century Spokane neighborhoods

Say you live in one of Spokane’s mid-century neighborhoods.

Leafy streets. Families in their 60-year-old houses. The very picture of a quaint, wholesome American neighborhood.

But there might be something ugly hidden deep in the history of the home: A whites-only covenant.

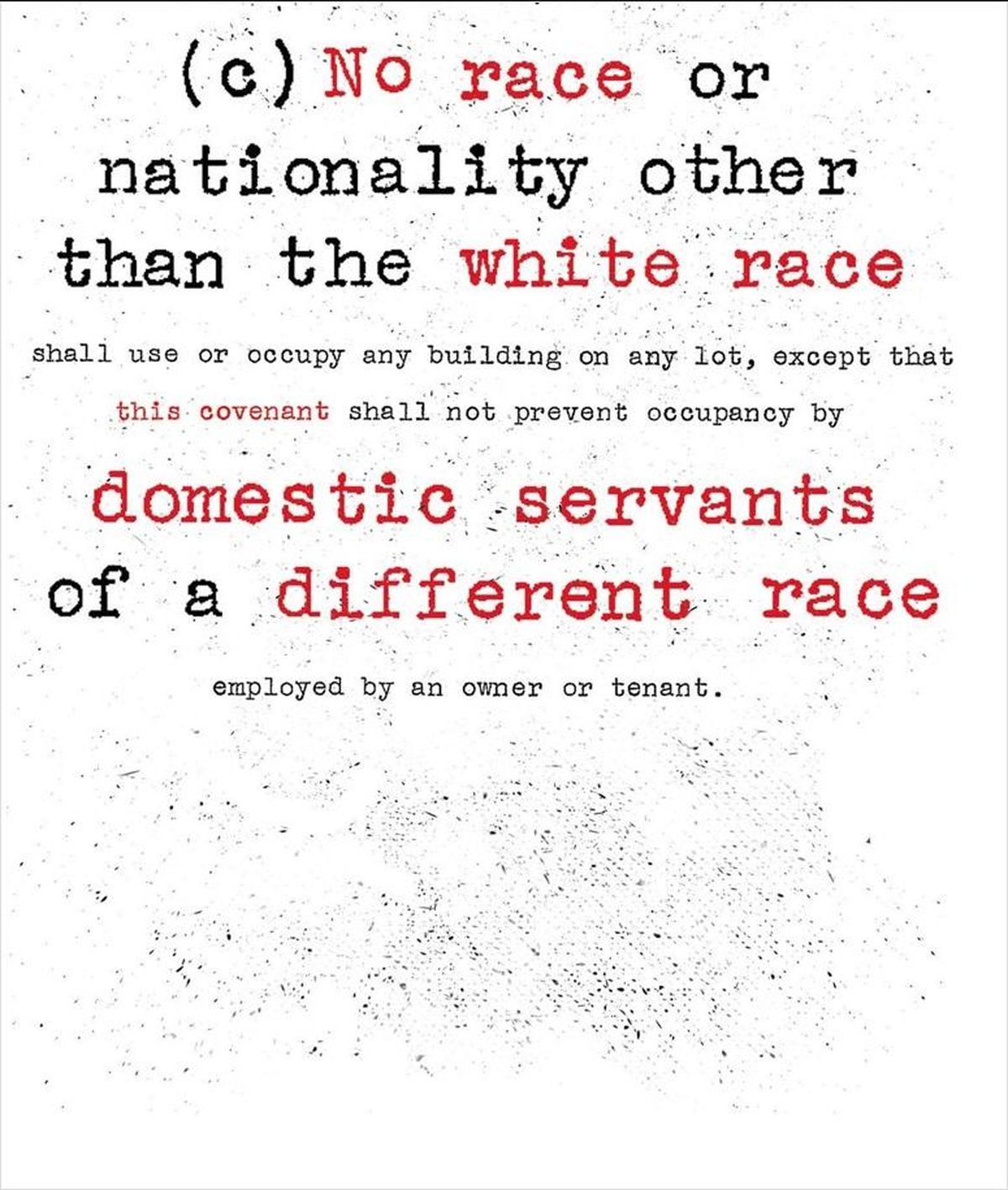

“No race or nationality other than the white race shall use or occupy any building on any lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race or nationality employed by an owner or tenant,” reads one such covenant for an addition in the Comstock neighborhood.

In more than 30 plats or subdivisions across Spokane County, such covenants still exist, legally attached to the deeds of homes on the South Hill, the North Side and Spokane Valley in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s. Even after the Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional and unenforceable, they were written and applied to new additions by developers and though they no longer carry the authority of law, they are still on the books, filed as part of a property record with the county auditor.

Logan Camporeale, a 27-year-old graduate student in history at Eastern Washington University, has been unearthing and compiling a list of Spokane neighborhoods with racist covenants. It’s taken intense historical detective work: Combing through the auditor’s website and historical archives, poring over large, decades-old property atlases to locate lots and boundaries.

“My goal is to see these things go away,” Camporeale said. “I want them to not be on the books. … At the very least, I want people to be aware.”

He’s been contacting local officials, such as City Councilman Breean Beggs, and looking for ways to get the covenants excised. Turns out it’s harder than you might think. Beggs, who is also an attorney, has “lent his legal brain” to Camporeale’s project. He says the council couldn’t simply do it with one broad swipe. The way property law works, removing a covenant from a property requires a judge, and the most likely route involves individual homeowners taking on the initiative, effort and cost.

“Once it gets in the deed, it is there, and you can’t get it out of the deed without judicial action,” said Beggs.

The covenants are invalid, but still a part of the documentary history of the properties. In other words, if a buyer purchases a home in one of these neighborhoods today, the racist covenants could still be among the paperwork at closing – along with a notice that any covenant that discriminates illegally is no longer enforceable, said Angie DeArth, who has been handling closings in Spokane for 43 years.

“It would be in there,” she said.

Phil Tyler, the president of Spokane’s chapter of the NAACP, said this week he was surprised and disturbed to learn that such covenants are still on the books.

“I didn’t know those were still in there,” he said. “It’s a horrible remnant of Jim Crow right in plain sight.”

‘We were embarrassed’

Covenants are legally binding agreements between buyers and sellers on property use. They can create an array of restrictions, including the minimum value of buildings,fence height, and garage placement. In fact, it was just such a routine question that originally brought the racist covenants to Camporeale’s attention last summer.

He has a work-study assignment at the state archives at Eastern Washington University. One of his co-workers filled a request for a homeowner in the High Drive neighborhood who wanted to build a fence and needed to see the covenants; she discovered they included racial restrictions.

“At first, we were embarrassed,” Camporeale said. “You just have this perception that it didn’t happen here. That’s something that happened in the South. … That couldn’t be more wrong.”

Not long before that, Camporeale had come across a map of Spokane’s “Negro Population” in 1960. It showed an intense concentration of the county’s 2,424 African-American residents in just two areas: downtown and East Central. A few other spots across the county had small black populations – individual dots that represented 10 people each. There were no dots on the South Hill.

“When I heard of these restrictive covenants I said, ‘OK, this makes sense,’ ” he said.

Such covenants were one of the tools used to enforce a kind of segregation – Spokane may not have had Jim Crow laws, but there were many ways, formal and informal, in which racial divisions were policed and enforced. The result was clear-cut, and it shaped the city.

Jerrelene Williamson, the 84-year-old author and historian of Spokane’s African-American history, has lived almost all her life in Spokane. She said that growing up here as an African-American, it was always clear that certain places and parts of town were off-limits to her – whether it was stated explicitly or not. She said she knew of the restrictive covenants, and that other practices to segregate neighborhoods became apparent when she and her husband were looking to buy a home in the late 1950s.

“They just wouldn’t show you certain properties,” she said.

They bought their first home off East Sprague. A decade or so later, they moved to a neighborhood in the Spokane Valley. They would learn much later that the real estate company had approached the neighbors and asked them if it was OK to sell the home to a black family.

“The same things happened all over the country, and it happened here in Spokane too,” she said.

Around the country, housing discrimination essentially cut off black communities from home ownership and investment, and locked black families out of economic opportunity – forces that are apparent still in a yawning divide in family wealth between white and black Americans. The writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, in a 2014 essay titled “The Case for Reparations,” argued that decades of housing discrimination – on the heels of slavery and Jim Crow – were a large part of America’s “compounding moral debt” to African-Americans.

Critical to the systemic discrimination were various players in the housing market: buyers and sellers, real estate agents, lenders – and, to no small degree, the federal government. From the 1930s to the 1960s, the Federal Housing Authority engaged in and encouraged “red-lining” its loan guarantees – refusing to guarantee loans in black or low-income neighborhoods.

A project similar to Camporeale’s in Seattle has identified 416 such neighborhood covenants.

“The language of segregation still haunts Seattle,” according to the project’s website, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. “It lurks in the deeds of tens of thousands of homeowners living in neighborhoods outside of the Central Area and the International District.”

As in Spokane, many of the Seattle covenants specified that only whites, or Caucasians, may live on the property. But some of the covenants exclude specific races, such as this one: “The lot, nor any part thereof, shall not be sold to any person either of whole or part blood, of the Mongolian, Malay, or Ethiopian races, nor shall the same nor any part thereof be rented to persons of such races.

DeArth, the closing officer, said that 35 years ago, she handled the closing of a home sale with a racist covenant to an African-American couple. The covenant – which she ordinarily would have tried to keep out of the paperwork at closing – limited the number of black people allowed on the property to five.

She said the couple handled the mortifying situation with grace: “The husband said, ‘Well honey, I guess that means your mom can’t come visit us.’”

A slow evolution

As Camporeale began digging into the Spokane covenants, he first came across racially restrictive rules in certain South Hill neighborhoods: High Drive and Comstock additions, for example.

Later he found other such covenants on the North Side, around Audubon Park, and in the Spokane Valley. In addition to the racism of the documents, there was something else disturbing – many of them were signed and implemented after the Supreme Court ruled such covenants unenforceable.

“They put it in the deed after the United States Supreme Court ruled they couldn’t be enforced,” Beggs said. “That is the most interesting thing to me.”

Some of the South Hill covenants were implemented in transactions of land owned by William Cowles Jr., of the family that owns The Spokesman-Review. Betsy Cowles, chairman of the newspaper’s parent organization, the Cowles Co., said Friday, “It isn’t clear to me exactly what role William Cowles Jr. had in the overall development at that time. What is very clear is that such racial segregation is offensive and in no way represents our company or family values. Today, we are proud of the work we have done and will continue to do in our companies and community to celebrate diversity and honor differences.”

The legality of such discrimination underwent a very gradual evolution. In 1917, the Supreme Court ruled that the government could not legally discriminate on racial grounds, but left open the door for property owners to discriminate through covenants and other restrictive contractual agreements.

Throughout the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s, segregation in Spokane operated out in the open in many restaurants, hotels, social clubs and other social settings. Carl Maxey, Spokane’s first prominent black attorney, became a towering civil-rights figure in part for his courtroom battles over segregation. In the 1950s, he and a local real estate agent held debates on housing segregation.

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that such covenants violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution and were not legally enforceable. But such covenants still were used in Spokane and elsewhere for years after the fact, and in combination with private, social forms of enforcement, still operated to segregate neighborhoods.

A crucial piece of this systemic discrimination came from federal mortgage-guarantee policies, which were tethered, in part, to the idea of maintaining stability and home values in neighborhoods. In the 1930s, the Federal Housing Authority encouraged discrimination explicitly in its guidelines for offering mortgage insurance: “If a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes.”

And, of course, the discrimination was also propped up by individuals, regardless of what the laws said. In Spokane in 1961, for example, a black man named Frank Hopkins, who owned a café in town, bought a North Side home outside the traditional black neighborhoods; before he could move in someone broke 28 windows in the home.

“I just had to let it go,” he told The Spokesman-Review at the time.

In practical terms, the covenants were not rendered moot until the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968. At that time, the federal government began refusing to insure home loans unless the seller certified that they would not discriminate against buyers.

A brief article in the Spokane Daily Chronicle in that year reported this change, and – without mentioning the covenants or the nature of them – noted the neighborhoods affected by the change in policy: They included several of the ones with covenants Camporeale has found.

Some of the covenants were set to renew automatically every 10 years; a handful have expired and in at least two cases, the racially restrictive covenants were formally “released” by the property owners who originated them.

Camporeale believes he’s located most of the pertinent records. But because they are decades old and were filed in various forms, he can’t be certain. A homeowner, to be absolutely sure, would have to track the record for their own property.

‘Get rid of them’

At this point, the question is: Does it matter if they’re still on the books if they have no legal authority?

To Camporeale, it matters. Imagine moving into one of those neighborhoods if you’re a person of color and discovering that document attached to property you legally bought, he says. Imagine reading it over while signing closing documents on a home.

Beggs said the covenants live on as a “stain of racism” in the community, but said there are few remedies. Camporeale had initially hoped the City Council could take a sweeping action, but it turned out to be more difficult than that. The covenants are already illegal and unenforceable, but the way property laws work, the covenant can only be removed through a specific judicial action, Beggs said. Otherwise, the document lives with the property forever.

That means the responsibility would probably fall to individual homeowners, or to homeowner associations, who would have to petition a court to strike the discriminatory language from the record, under a law passed 10 years ago by the Legislature. It wouldn’t be a huge burden, but would take a little time and effort and would cost homeowners a filing fee of $20 plus any attorney fees. Beggs said he’s looking into the possibility of creating a resource for homeowners – a clinic or other event with law students, perhaps – to help with that process.

Vicky Dalton, Spokane County auditor, said she understands why people would object to the covenants, but that her office has a duty to record the history of the community. She said covenants could be revoked, but shouldn’t be erased.

“We preserve the original document so history is not erased,” she said. “History is what happened. There were terrible things that happened in the past, and we shouldn’t hide from them. We should face them.”

Camporeale shares the interest in preserving history, but said he thinks the covenants should be relegated to history and he’d like to see a way to distinguish between an archival record and the current, working file – even if that file contains caveats.

“I don’t want to erase this stuff,” he said. “I want everyone to know it happened.”

Williamson, who experienced it all firsthand, was not surprised to hear that the covenants are still on the books. In her mind, there’s no question about what should be done.

“We should get rid of them,” she said.

Shawn Vestal can be reached at (509) 459-5431 or shawnv@spokesman.com. Follow him on Twitter at @vestal13.