‘Back to the darkness’: Afghan women speak from Taliban territory

Loading...

| LONDON; AND KABUL, AFGHANISTAN

The Afghan student says she will never forget one of the Taliban’s first acts after seizing control of her district weeks ago, amid a military advance that has swiftly accelerated as American troops leave Afghanistan.

Late at night, Khalida was awakened by a deafening explosion. From her roof, the 18-year-old saw flames rising from her girls high school – her pride and joy, with a new library full of books painstakingly collected by teachers who traveled to gather them.

“I cried a lot. The villagers tried to put out the fire, but the Taliban shot at them and no one saved our school,” says Khalida, recalling an event that has become a regular feature of the Islamist militants’ conquests, as Afghan security forces collapse in district after district.

Why We Wrote This

Taliban political leaders said they had reformed and modernized while out of power. But in territory captured by their fighters, the feared regression on civil rights especially impacts women.

“In the morning, when I went to school, everything was burned and destroyed, even the school gates,” she says of the school built by Norway and the United States in northwestern Faryab province.

“When I saw the Taliban up close, I was very scared. They are wild people and they don’t respect women,” says the student, who gave only her first name and who planned to become a doctor. “No one is happy with the Taliban; everyone is sick of them. ... [But] no one is willing to stand up to the Taliban. [They] will kill you. They are very cruel.”

Top Taliban political leaders – who negotiated a withdrawal deal directly with the U.S. in 2019 and 2020, and then joined intra-Afghan peace talks last September – have proclaimed a pragmatic, moderate evolution in their thinking since the late 1990s, when their version of Islamist rule was marked by violence and strict enforcement of bans on girls’ education, women working outside the home, and even men shaving their beards.

Yet today, residents of areas that have fallen under Taliban control report little sign of change, reform, or inclusive accommodation by the jihadis of a society molded by 20 years of a Western presence and tens of billions spent on rebuilding. Those investments raised many Afghans’ expectations of a freer future.

Instead, these residents confirm it is the “old” Taliban – every bit as brutal, zealous, and vengeful as they were two decades ago – that are again seizing control, and through their oppressive actions providing a glimpse of the future under their archconservative sway.

The Taliban’s march across Afghanistan surged on multiple fronts since President Joe Biden vowed in April that U.S. and NATO troops would withdraw unconditionally, ending America’s longest-ever war. By Tuesday, the Taliban fully controlled 223 of Afghanistan’s roughly 400 districts, three times the number controlled by Afghan security forces, according to the Long War Journal.

“We thank the U.S. government for transforming our lives and giving us hope after the dark days of the Taliban; only in the last 20 years we realized that we are human beings and have the right to live,” says a women’s rights activist in Faryab province, who asked not to be named for her safety.

“Unfortunately, the current situation in the country is we are going back to the 1990s. It means we go back to the darkness,” says the activist, whose district of Shirin Tagab fell to the Taliban a month ago.

“All Afghans, especially women, are suffocated by the recent actions of the U.S. government,” she says. “The U.S. should have defeated this ominous phenomenon on the ground, or forced them to make peace. But they introduced the Taliban as a power to the world [through direct negotiations], and did not realize the Taliban are the savage Taliban, who know nothing but terror.”

She saw signs of Taliban intolerance last October, as she prepared for World Teachers’ Day at a local girls school. Money had been raised for a party, but a new computer lab at the school prompted local “radicals” to start a rumor that immoral films were being shown, and that “days of infidelity” were to be celebrated, she says.

The night before the event, Taliban fighters crept past guards and burned down the school.

“We wrote a letter to the Taliban and asked them to work together to build a peaceful Afghanistan, to provide education for the future ... to teach the young generation the lesson of self-confidence, mutual acceptance, and national unity,” says the activist. “But the Taliban threatened to kill me and my father in response.”

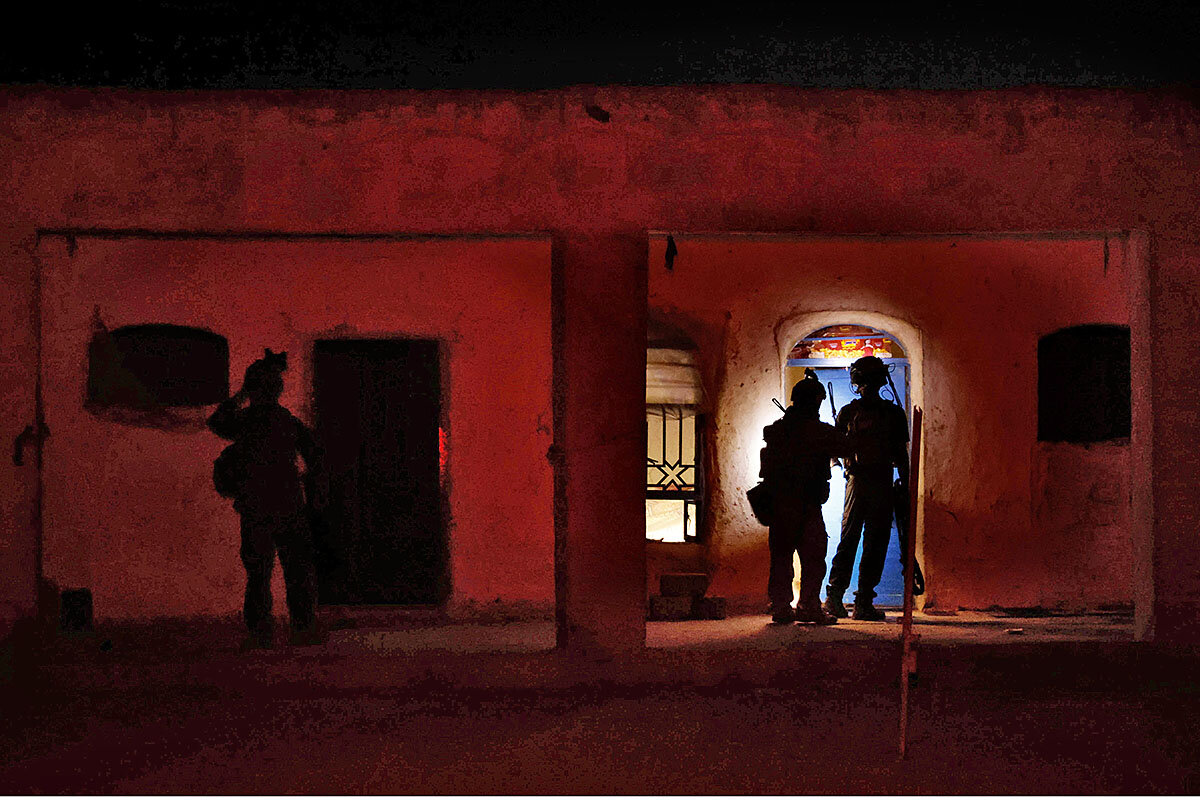

This month, American forces withdrew from their last base at Bagram in the dead of night, more than two months ahead of President Biden’s deadline.

As peace talks have stalled, signs from the battlefield indicate the Taliban are now pursuing “military victory” and that “provincial capitals are at risk,” Marine Gen. Kenneth McKenzie, the chief of U.S. Central Command, said this week.

“I don’t think the Taliban political leadership were expecting the kind of gains that they had over the last 1 1/2 months, which itself raises questions about differences between [them] and military commanders,” says Timor Sharan, a former deputy minister in the Afghan government.

“If they occupy more ground, and we increasingly see [local] commanders going back to the way they have known – which is limiting women, closing girls schools, wedding halls, and so forth – I think there is a serious gap here, within the Taliban itself,” says Mr. Sharan, director of the Afghanistan Policy Lab.

“My fear is that the Taliban political leadership is losing their control over events on the ground,” he says.

A longing for freedoms

That could impact how easily the Taliban can impose their will on a population that largely rejects their strict interpretation of Islam.

The Afghanistan Analysts Network said that research it published this month, for example, “challenged the idea that women in rural areas are satisfied by what is often portrayed as ‘normal’ by the Taliban or other Afghan conservatives.”

“Almost every woman we spoke to, regardless of the political stance and level of conservatism ... expressed a longing for greater freedom of movement, education for their children (and sometimes themselves),” the Kabul-based think tank said.

And yet, from their first days of control in each district they capture, the Taliban have instructed Afghans – often using mosque loudspeakers, printed instructions, and megaphones in marketplaces – that women must wear the all-enveloping burqa, and always be accompanied by a male guardian.

Some Taliban insist on payments of food or cash, or that each village produce 20 fighters for their cause. Others ordered that girls over 15 years old be provided as wives. Still others prohibit watching television, or using mobile phones.

Human Rights Watch last week documented mass forced expulsions and the burning of homes by Taliban fighters in northern Kunduz province. And everywhere, girls’ education and women’s rights are being rolled back.

“They swear to the people that all their restrictions and laws are in accordance with Islam, that whoever violates them is an infidel and their death is permissible,” says Sayed Hassan Hashemi, a civil society activist in Faryab, who has seen the aftermath of five Taliban school burnings.

“Taliban actions are different from their [leaders’] speech, as the ground is different from the sky,” says Mr. Hashemi, whose district is now under Taliban control. “The Taliban leaders in Qatar live in luxury homes, they and their families enjoy life, but they don’t know what injustices their fighters do on local people.”

“First we close the schools”

An official Taliban statement July 12 by spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid called the reports of abuse “enemy fabrications” and said statements attributed to the Taliban “that impose restrictions on locals, threatens them, specifies gender laws, regulates lives, beards, movements and even contains baseless claims about marriage of daughters” are not real.

Yet the Taliban on the ground are not shy about their aims.

“When we take a village, we sleep in the mosque, we don’t bother people in their homes,” a Taliban commander identified as Mollah Majid told France 24 this week, near the northwestern city of Herat.

“But the first thing we do is close down the government-run schools,” he said. “We destroy them [and] put in place our own religious schools, which follow our own curriculum, in order to train future Taliban.”

That is the concern of one teacher in northern Mazar-e-Sharif province, whose district recently fell to the Taliban, and who asked not to be named.

“In the beginning, when we saw the Taliban interviews on TV, we hoped for peace, as if the Taliban had changed,” says the teacher, who experienced their rule in the 1990s. “But when I saw the Taliban up close, the Taliban did not change at all.”

New rules “are not tolerable, because women get used to a free life for 20 years, so it is very difficult for them to live under the restrictions,” says the girls schoolteacher.

“When I see the Taliban, I feel that I see the enemy of my religion, culture, and traditions,” she says. “If we surrender to the Taliban, the future ... will also be dark. So my message to the whole new generation is to fight until the last moment.”