More than a century after he was exonerated, Alfred Dreyfus, the Jewish army officer whose false conviction for treason sparked bitter controversy, has erupted into France’s presidential race amid far-right attempts to question his innocence.

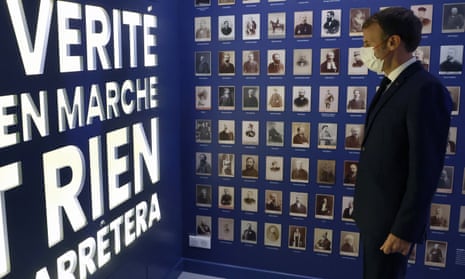

Emmanuel Macron last week personally inaugurated the first museum dedicated to the Dreyfus affair, a historical collection exhibited in the house of Émile Zola, the writer and best-known defender of the persecuted officer, in Médan west of Paris.

In the presence of the artillery captain’s descendents, the French president said nothing could repair the humiliations and injustices Dreyfus had suffered, but added pointedly: “Let us not aggravate it by forgetting, deepening or repeating them.”

Macron particularly stressed the continuing need to combat the antisemitism behind the officer’s persecution. “I say to the young: forget nothing of these fights,” he said. “In the world in which we live, in our country and in our Republic, they are not over.”

The comments were widely interpreted as targeting Éric Zemmour, the far-right, anti-immigrant TV pundit and polemicist who, despite not having declared his candidacy, is predicted by some polls to reach the second round of April’s presidential election. Zemmour has claimed France’s collaborationist wartime leader, Philippe Pétain, saved the lives of French Jews, rather than assisting their deportation to Nazi death camps, and has repeatedly said the truth about Dreyfus was unclear.

“Lots of people were ready to clear Dreyfus, but this affair is murky,” Zemmour, 63, told one TV show late last year. “We will never know” whether the allegations against him were lies, he said on another, adding that his innocence was “not obvious”.

Macron also suggested after his inauguration of the museum, which contains more than 500 exhibits and was co-financed by Pierre Bergé, the late partner of fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent, and anti-racism campaigners, that the army could consider posthumously promoting Dreyfus to the rank of general.

The officer’s exoneration has long been viewed as an affront to national pride by France’s far right, and historians say Zemmour – whose parents were Jewish Algerians with French citizenship – is far from the first ultra-nationalist to dispute his innocence.

An army colonel was cashiered in 1994 for publishing an article suggesting Dreyfus was guilty, prompting a lawyer for Jean-Marie Le Pen, the former far-right leader, to claim the captain’s exoneration had been “contrary to all known jurisprudence”.

Other far-right writers have argued the Dreyfus affair was “orchestrated” by “a secret and occult power” and “seriously weakened France” in the run-up to the first world war by undermining “national identity and pride”. More recently, said historian Marc Knobel, who advises the government on anti-racism and antisemitism, ultra-nationalists have made concerted attempts to rehabilitate far-right figures such as Marshal Pétain and Charles Maurras.

“The far right has become less inhibited about the past, less defensive about the accusations of treason, dishonesty, division and collaboration levelled against it,” Knobel wrote in La Revue des Deux Mondes. “Proclaiming the possible guilt of Alfred Dreyfus is not an accident – it’s part of a revisionist strategy.” Zemmour, he said, “claims to like history. But history is not a weather vane that moves according to mere ideology. It’s a science.”

History is, of course, sometimes revised, but “through study, through the discovery of new archives, new witnesses. Knowledge is obviously not fixed,” Knobel said.

But as far as the Dreyfus affair was concerned, “historians and researchers have been exploring this vast field of study for decades. And they continue to demonstrate, unanimously, the innocence of Alfred Dreyfus. Only Zemmour spreads suspicion.”

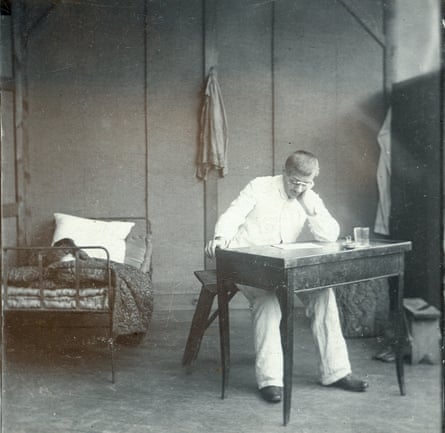

Dreyfus was convicted by a secret court martial in 1894 of passing military secrets to the Germans and, after being ceremonially stripped of his rank and having his sword snapped, sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island in French Guiana.

As the army tried and failed to cover up the guilt of another officer, Major Esterhazy, of the crime, France split into two bitterly opposed camps: the anti-Dreyfusards, right-wing nationalists convinced of his guilt, and Dreyfusards, mainly left-wing anti-militarists. “J’accuse”, Zola’s celebrated open letter to the president accusing the government of antisemitism and unlawful imprisonment, was published on the front of L’Aurore newspaper on 13 January 1898, earning the author a libel conviction.

Later in the year, the editor of the Observer, Rachel Beer, tracked down Esterhazy, who was in hiding in London, and published his confession to the crime.

Mounting public outrage eventually led to Dreyfus appearing before a new court martial in 1899, which again found him guilty. In a move designed to save the army’s face, he was pardoned and released from prison by the new president, Émile Loubet, but not officially exonerated until 1906.