- India

- International

A Legacy of Caste in Latin America

Underlying the framework of today’s modern racial terminologies and racial thought, in places like Mexico, Cuba, Peru, Argentina and Brazil, is an architecture created by caste.

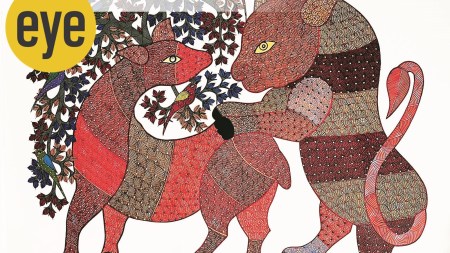

Open caste made caste easier to survive in places like Mexico. (Illustration by C R Sasikumar)

Open caste made caste easier to survive in places like Mexico. (Illustration by C R Sasikumar)There are few places you can go in the world that have not been touched directly, or indirectly, by caste. After spending my entire adult life studying the history of race and caste in Latin America, I’m convinced that the vocabulary of race used in most countries throughout the region owe their existence to caste categorizations that flourished in the early modern world. In other words, underlying the framework of today’s modern racial terminologies and racial thought, in places like Mexico, Cuba, Peru, Argentina and Brazil, is an architecture created by caste.

If you travel to Latin America today, depending on which countries you visit, you might encounter people described as mestizos, cholos, zambos, morenos, or mulatos. Without going into the meaning of these categories in detail, they all refer to various racial groups—essentially mixtures of black, white, Asian, and native populations. Hundreds of racial categories have been used throughout the region over time.

If you could visit these same Latin American countries during the 17th or 18th centuries, you would find the same categories described not as races, but as castes. In other words, tracing the genealogy of race to caste is linear and direct. But why and to what effect? Why were these categories created, and what does this mean for the legacy of caste in Latin America, and other parts of the world?

If you could visit these same Latin American countries during the 17th or 18th centuries, you would find the same categories described not as races, but as castes. In other words, tracing the genealogy of race to caste is linear and direct. But why and to what effect? Why were these categories created, and what does this mean for the legacy of caste in Latin America, and other parts of the world?

The reasons for creating caste in Latin America are clear. In the aftermath of the 16th century conquests, through which Europe came to dominate the Caribbean, as well as South and Central America, the Spaniards and Portuguese found themselves short-handed. Particularly in the sprawling empires of the Incas and Aztecs, which had millions of inhabitants throughout Mexico and Peru, the small handful of Spanish conquerors were at a huge numerical disadvantage. Without the ability to directly govern everywhere, a method of indirect control had to be devised so that the massive populations of the empire could partially regulate themselves. Furthermore, the small, foreign, white elite had to legitimize their authority in Latin America, where they were essentially intruders. Color became a convenient, albeit inaccurate shorthand for intellectual intelligence, Christianity, talent, and governing authority. In an enormous empire, European colonists had to be able to quickly recognize, by sight, which populations were supposed to be subordinate to them.

Another precipitating factor for the rise of caste was how the New World quickly became a magnet for new strangers. On the same ships boarded by Europeans also came Africans, South Asians, Chinese and Japanese immigrants, some of whom were slaves. Clustered principally into the New World’s growing towns and cities, and with low numbers of female immigrants, these new populations began taking native wives and also began intermingling with each other. Imbalanced power dynamics further unleashed whites to engage in miscegenation with whomever they chose. These processes happened fast and uncontrollably. Racial mixture in the early days was uncorked and intense. If Spanish and Portuguese governance was to have any chance at success, the emerging racially-mixed children had to be assigned a place in the social order. Barriers needed to be erected to restrain racial mixture from overtaking the colonies and replacing the white elites themselves. This ongoing saga comprises a silent story underlying the framework of the Spanish and Portuguese empires, and is part of the untold background of the region today.

But the sheer pace of racial mixture, and the suddenness with which new groups started appearing in the New World, created a different fate for caste than in places like India. Also, religion was not at the core of caste. The mission to spread Christianity was certainly used to justify Spain and Portugal’s activities of conquest in Latin America. However, they did not create a parallel to the Brahmin caste, even though the priesthood and university education was largely reserved for white elites.

Latin America’s priests and clergy did their best to help manage caste boundaries in places like Mexico. They tried to regulate which groups could marry each other. They assigned birth certificates that marked one’s caste station. They served as authorities who attested to an individual’s purity of caste to attain certain positions in society, and they investigated caste transgressions as they pertained to questions of faith. But priests were frequently bribed, un-sanctioned marriages took place everywhere, and some forbidden castes even slipped into the coveted ranks of the clergy themselves. The power of religion over caste was weak.

All of this created a different caste system than you might recognize. I call it an “open-caste system.” Effectively, caste boundaries did work…sometimes. Caste boundaries were strongest when someone clearly, and very visibly belonged to a restricted group. But even here, slippage happened. Ultimately, the Spanish and Portuguese authorities selectively enforced caste regulation over the centuries because if they were too restrictive, they might have lost their ability to rule. Over time, they learned that keeping an open door into (and out of) some caste categories, allowed them to replenish their precious ruling groups in a vast and daunting empire.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

That some people could conceive of themselves as members of the governing caste (although they were not) was convenient and helped the authorities govern in places where they did not have a sustained presence. Some regions were so remote that royal authorities rarely visited them. But they did receive taxes and tribute payments from such distant places. Finally, the government and Church knew that they could always tighten caste reins when deemed necessary—a practice that eventually became harder to enforce as the centuries passed, and ruling castes became more diluted.

In an open-caste system, change to the composition of the ruling caste was inevitable. War, revolution, industrialism, and capitalism, compelled even more change. Large fortunes and power amassed in the colonial period by the elite did not always survive when colonies became nations. Certain upstart families took advantage of the wars of Independence, and other opportunities, to seize wealth, power and prestige. So the colonial-era vision of what a ruling caste should look like was fated to crumble over time in Latin America. What is interesting to me, however, is that the early vision did not completely vanish.

An unknown secret is that open-caste, despite altering who could be members of certain caste groups, actually enabled caste’s long term survival in the region. Thanks to the open-caste system, caste was able to shift, change, and adapt over time. In this way, as the concepts of race began to emerge in the Western world, caste proved malleable, and able to ease into the background of race. In the Western world, race would ultimately trump caste. Race, as a classification system that was better adept at describing human mixture from a scientific standpoint. As science and empiricism became hardened into European thinking through the Enlightenment, race was deemed more ideologically aligned with modernizing societies. Caste was seen as more out of date.

Nonetheless, few could appreciate the effects of open-caste as it silently melded with emerging notions of race. As ancient caste practices in Latin America gradually faded, they continually informed modern race—dictating that there would be great latitude and tolerance of racial difference in modern Latin American societies, because behind tolerance was a much deeper goal. That goal was a form of greater, and more encompassing hidden control that took cues from how people looked, lived, and acted. This method of control gave a wide spectrum people sufficient slack to operate in various un-prescribed ways in their societies, but also eventually preserved closed doors to some of those people in the most coveted areas of social access, and in situations where it mattered most. History shows that open-caste operated this way in the distant past, and has probably continued whispering these goals into the way race operates in Latin America today.

Ben Vinson III, the author of Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico, is the Provost and Executive Vice President of the Case Western Reserve University

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

May 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05