American Kids Can Wait

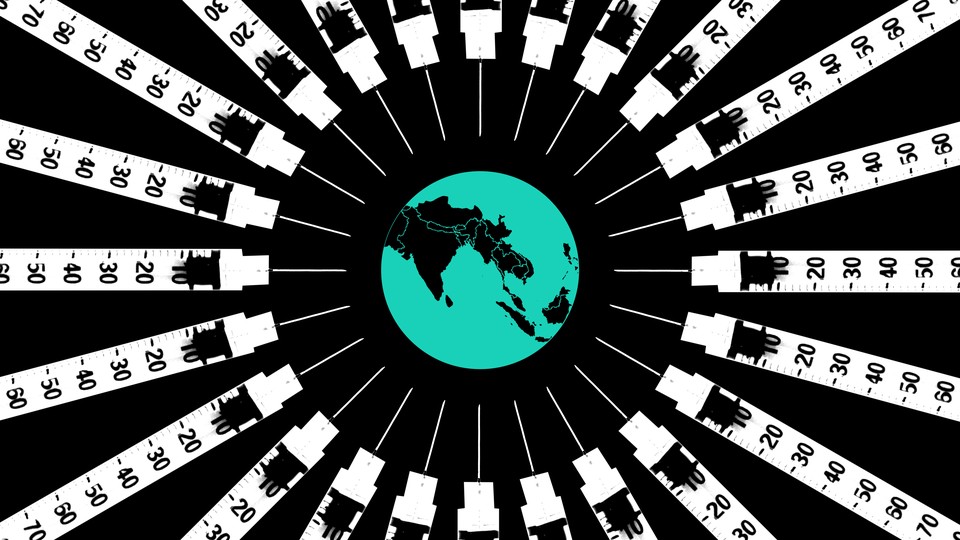

The U.S. should delay shots for children until global vaccine-manufacturing capacity significantly expands and the crisis in India subsides.

Updated at 12:27 p.m. ET on May 24, 2021.

In the coming months, the United States and other rich nations will have the opportunity to save hundreds of thousands of lives threatened by COVID-19 in South Asia. On Monday, the FDA authorized the emergency use of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in children ages 12 to 15. But in the name of global equity, Americans should delay vaccination of our own children until global vaccine-manufacturing capacity significantly expands and the crisis in India subsides. Such a delay would mobilize tens of millions of additional doses, which could be used almost immediately in hard-hit regions overseas. Especially now, as the supply remains limited, leading nations should work to ensure that doses go where they will do the most good for public health.

Allowing the export of doses would be not only effective vaccine diplomacy but also in Americans’ own interest. Gaining better control of the disease across the globe would prevent or slow the emergence of worrisome viral variants.

For the U.S. to focus on preventing sickness among American children before turning its attention abroad might seem only natural. But the imminent danger to adults in global hot spots is simply too great and demands attention now. Compared with children ages 5 to 17, people ages 75 to 84 are 3,200 times more at risk of dying from COVID-19. For children, the risk of disease is not zero, but the mortality risk is comparable to that from seasonal influenza, and hospitalizations occur in only about 0.008 percent of children.* Recent studies have provided reassurance that long-term COVID-19 and post-COVID heart problems in children and young adults are rarer than initially feared. A small number of children have conditions—including immune deficiencies, certain cancers, and severe obesity—that put them at greater risk of harm if they contract COVID-19, and in these unusual cases, vaccines need not be delayed.

In general, though, research has consistently found that children are less likely to catch and transmit COVID-19 than adults are, and even in places where the more infectious B.1.1.7 variant is dominant, children do not appear to have driven the increase in infections and hospitalizations earlier this year. Among people 19 and younger, COVID-19’s reproduction number has been estimated at less than 1. This means that, on average, an infection spreads to less than one additional person—the threshold under which the disease begins to die out. By contrast, the reproduction number among adults ages 20 to 49 is higher than 1. These adults are thought to be responsible for more than 70 percent of all infections nationwide, even after most school-closure mandates were lifted.

Fortunately for the United States, the incredible power of vaccines is becoming more and more evident. As of Monday, 46 percent of all Americans have received at least their first dose of one of three COVID-19 vaccines—which until Monday’s decision had been approved in the U.S. only for people older than 16 or 18. Israel and the United Kingdom—where 63 percent and 51 percent of the population, respectively, has received at least one dose—have rolled out vaccines even faster. In all three nations, rising levels of adult vaccinations have led to reductions in cases among all age groups, including (unvaccinated) children. This is because vaccines prevent not only infection (as well as hospitalization and death) for the individual recipient, but also transmission to other people. Britain has such low case counts that experts there recently downgraded the health threat “from a pandemic to an endemic situation.” More important than the drop in new cases is the plunging number of hospitalizations and deaths, even as the B.1.1.7 variant has come to account for 60 percent of U.S. infections. The vaccines are defanging the virus. In these three highly vaccinated countries, life is returning to normal.

In India, however, only 9.8 percent of the population has received a first vaccine dose, the health-care system is collapsing, and a humanitarian catastrophe is unfolding. Countries with low vaccination rates are all at risk of a similar fate. The World Health Organization has called for prioritizing the vaccination of those at greatest risk from infection and those most at risk of spreading the virus. Thankfully, children rank lowest on the priority list by either criterion.

Even so, many American parents might assume that vaccinating children is essential to their return to pre-pandemic life. Yet despite the benefits of eventually securing shots for them, doing so is not a matter of immediate urgency. It should not be a requirement for reopening schools. As adults gain immunity from vaccines or previous infection, children will also be afforded protection. COVID-19 rates in children have consistently reflected those of adults in their community. For every 20-point increase in vaccination among adults, one recent study found, the risk of transmission to children halves. The most important thing U.S. policy makers can do to protect children in the next school year is to encourage their parents—and all adults—to get vaccinated.

Meanwhile, by donating vaccines to countries with the worst COVID-19 outbreaks, the United States could help save lives quickly. Despite a common perception that vaccines require weeks to work, a reduction in the number of symptomatic coronavirus cases was evident in clinical trials as soon as 10 days after participants got their first shot. Because symptoms take several days to appear, vaccines’ protection may kick in just days after administration. Such protection is all the more important under the catastrophic conditions now evident in India. The Biden administration last week announced its support of waiving intellectual-property protections in order to accelerate the deployment of vaccines to where they are needed most. Many public-health experts are pushing for rich countries to donate surplus vaccine doses to South Asia. Postponing the vaccination of most American children may have an even more immediate effect on the supply of doses.

The U.S. must use the available science to everyone’s advantage rather than take a purely nationalistic approach that risks lives in the short term and is likely to be less effective against COVID-19 over the long term. An equitable and science-based approach will not only save lives now, but set a precedent for better global pandemic cooperation in the future.

*This article previously misstated that hospitalizations occur in about 0.008 percent of children with diagnosed COVID-19 infections. In fact, hospitalizations for COVID-19 occur in about 0.008 percent of children overall.